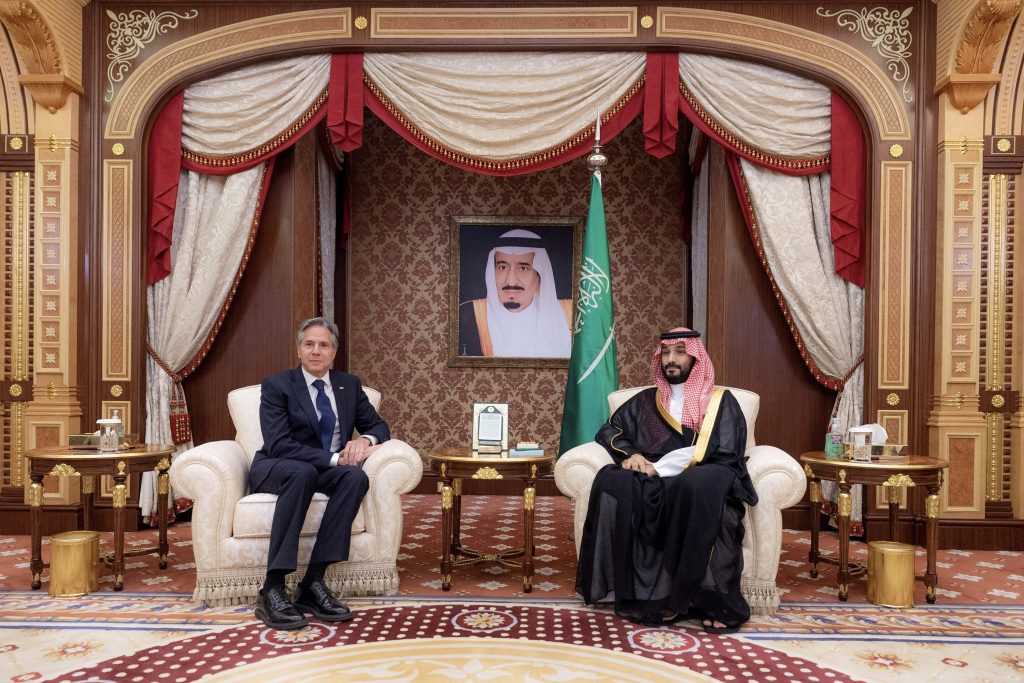

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken arrived in Saudi Arabia on Tuesday at an especially delicate moment in the kingdom’s relationship with the United States. While the secretary’s visit will involve a litany of policy objectives and discussions across various sectors, its overarching goal is almost certainly singular: to put relations back on a more stable track.

Those relations have waned and waxed since US President Joe Biden went to Jeddah almost eleven months ago. They were strained by the Saudi-driven OPEC+ decision in October 2022 to cut oil production and Biden’s promise for a full-scale review of the US relationship with the kingdom. Conversely, they have been enhanced by Riyadh’s choice of Boeing to build planes for its new airline and US efforts to soften the ground by sending multiple emissaries to improve bilateral ties.

Officials in both Riyadh and Washington sense the seesaw nature of the relationship. Among the few areas of complete agreement is that both countries would prefer something more stable. Stability will not equate to agreement on all issues, but it could mean establishing clearer expectations and agreeing to avoid surprise decisions.

Saudi domestic policy is driving its foreign policy

Too often, countries underestimate or forget just how much other countries’ foreign policies are simply a reflection of domestic priorities and politics. Saudi Arabia is a case in point. However they might appear from the outside, Riyadh’s foreign priorities today are little more than a shadow of its domestic policy. Saudi officials’ single overriding goal is to create, in record time, a vibrant and diverse economy to ensure the kingdom’s wealth and regional hegemony long after oil is no longer the world’s dominant energy source.

The challenge to accomplishing this is enormous. Vision 2030, the plan under which the kingdom’s proposed renaissance is being developed, has made some progress. Participation of Saudi women in the workplace is now nearly 36 percent, up thirteen percentage points since 2017. Government revenue from sources other than oil is also trending in the right direction, growing 5.8 percent in the first quarter of 2023, after it grew 6.2 percent in the fourth quarter of 2022. Other areas remain deficient. For example, the goal of having the private sector account for almost two-thirds of gross domestic product is likely to be missed by a wide margin. Reaching all of the Vision 2030 targets is going to be a Herculean challenge, but the amount Saudi Arabia plans to invest in that effort—estimated to be more than three trillion dollars in total—is also unprecedented.

Saudi officials realize that funding Vision 2030 is only possible if oil prices remain high. Hence their decision to cut oil output again on Sunday and their confidence that they were right to do so this past April and October. Relatedly, Blinken and his team should not be surprised if Saudi officials continue to look east, especially to China. Riyadh is unlikely to negotiate with the United States over Saudi Arabia’s symbiotic commercial relationship with China, given that China remains the largest importer of Saudi crude oil.

At the same time, Vision 2030 has no chance of immediate or sustained success if the kingdom is lacks the requisite physical security to be a regional and global commercial hub, a safe place for foreign investment, and a tourism, entertainment, and sports destination. That requires a sufficient level of security, backed by defensive weapons and technologies that can protect the skies over Saudi Arabia and its people and infrastructure on the ground.

A new paradigm for understanding Saudi foreign policy

To support this goal, Riyadh wants to forge its own path—a nonaligned one that minimizes the influence of China or the United States over the country’s economic or national security. For example, Saudi officials appear interested in developing an indigenous Saudi defense industry. More to the point, they want US defense companies to help develop it through business-to-business efforts. Yet this should be a nonstarter if it cuts out the US government, which has spent years building and revising requirements for the sale of weapons.

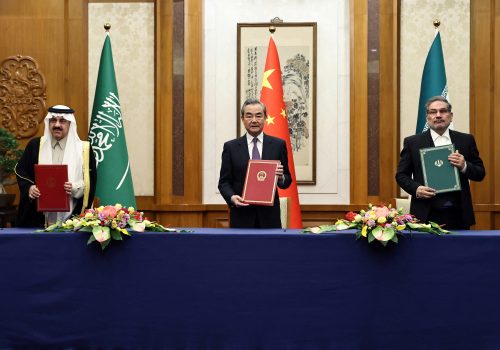

It’s through this prism of inward focus, nonalignment, and a desire for minimal external influence that Blinken and other US officials should seek to understand Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy. That prism helps clarify, for example, why Saudi Arabia agreed to rapprochement with Iran in March. It also can help clarify why, when the United States declines to sell certain military hardware nowadays, it’s no longer the end of the conversation. Rather, it’s the beginning of a new one for Saudi Arabia to have with European Union members, Turkey, or especially China, which doesn’t have the restrictions and end-user requirements that the United States places on its weapons sales.

Does Saudi Arabia want a strong security and commercial relationship with the United States and Europe? Absolutely. But Riyadh also appears to believe, rightly or wrongly, that it is ready to succeed on its own. Whether or not such potential overconfidence is reasonable or misplaced, it should not factor into Washington’s decision-making as to the nature of the relationship it wants with Saudi Arabia. For Washington, the calculation is actually quite simple: Is a more robust relationship with Saudi Arabia better for US national security, including economic security? The answer is yes.

It’s in the United States’ interest to stabilize the traditional realms of the relationship, defense and oil; to further develop the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) as a real alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative; to make progress on technology and cyber issues; to expand opportunities for foreign direct investment in the country; to advance an integrated defense architecture in the region; and for Saudi Arabia eventually to normalize relations with Israel. Each of these topics is likely to be discussed this week during Blinken’s visit, though advancing on cyber, foreign direct investment, and the PGII are probably easier to achieve than successfully negotiating Saudi Arabia’s formal ties with Israel, which is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Blinken’s trip will almost certainly help to stabilize the relationship. But to achieve these broader strategic objectives, it will take a closer relationship, not just a more stable one.

Jonathan Panikoff is the director of the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council and the former deputy national intelligence officer for the Middle East.

The views expressed are the author’s and do not imply endorsement by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Intelligence Community, or any other US government agency.

Further reading

Tue, Mar 21, 2023

China’s mediation between Saudi and Iran is no cause for panic in Washington

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

The deal is a mere statement of intentions by both countries to improve relations, meaning reconciliation is not complete.

Wed, May 10, 2023

Saudi Arabia should consider the ‘Just Do It’ strategy for normalizing ties with Israel

MENASource By Richard LeBaron

Acting on one’s terms when pursuing national interests is always a better strategy. Saudi Arabia is completely capable of dealing with Israel on its own.

Tue, Mar 14, 2023

Improving Gulf security: A framework to enhance air, missile, and maritime defenses

Report By

Looking at decades of US support and operations in the Gulf and recognizing a continued, arguably growing, air and maritime threat from Iran, the Atlantic Council Gulf Security Task Force developed a framework on how to best protect US and allies’ interests in this sensitive, always relevant region.

Image: US Secretary of State Antony Blinken meets with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, June 7, 2023.