China’s mediation between Saudi and Iran is no cause for panic in Washington

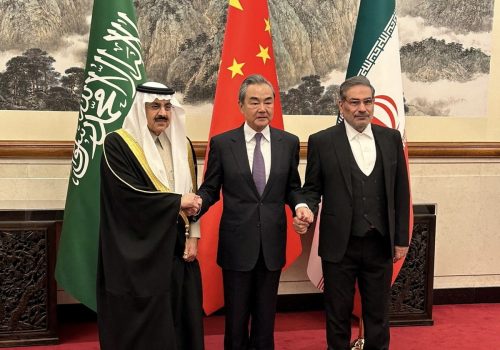

On March 10, Iran and Saudi Arabia surprised the world by announcing that they had signed a statement (mediated by China) —resuming diplomatic relations. If it holds, it will lead to a meeting at the foreign minister level in two months. Iran later said that Saudi King Salman invited Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi to visit the kingdom, following leaks that China plans to host an Arab-Iranian Summit in Beijing later this year.

The deal has the potential to shake the foundations of Middle Eastern politics. However, it is beset by Saudi-Iranian mutual distrust that runs deep in their strategic thinking and a wide range of regional conflicts—Yemen, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria—that serve as a battleground for their competition. In dealing with such abrupt breakthroughs, caution is always helpful to put conclusions based on panic and hasty assumptions into context. The deal is a mere statement of intentions by both countries to improve relations, meaning reconciliation is not complete. It could begin a new era of peace and stability, but it could also unravel anytime.

Riyadh and Tehran clearly wanted to hand over a diplomatic win to China, despite reassurances that the United States was kept informed all along—a stark warning of China’s growing influence over both sides and the United States’ diminishing clout over its Gulf partners.

China did not go out of its way to dent US credibility in the Gulf. Its mediating inroad is a natural result of President Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power at home after being confirmed for a third term in office. It is also consistent with its longstanding position in the Chinese Five-Point Initiative proposal for security and stability in the Middle East in 2021, which set out norms for China’s diplomatic vision in the region. China’s ambitions for building more diplomatic clout were reinforced in 2022 with another Four-Point proposal for a new security concept in the Gulf, which was meant to offset Washington’s alliance building and zero-sum Cold War mentality.

However, the statement unveils three shifts in Beijing’s vision for itself and the region. It confirms many experts’ concerns that China’s agenda is not passive and exclusively related to economic cooperation and the Belt and Road Initiative. In the past week, the debate has revolved around the assumption that China may have just started a journey towards a more significant diplomatic and security role in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

In addition, China has just operationalized one of its advantageous policy tools: the ability to capitalize on the unique trust of Riyadh and Tehran.

Furthermore, China has announced that it is ready to play the role of a responsible stakeholder on the international stage—a position the US has long pressured Beijing to assume.

But China’s role in mediating is more about optics than substance. More importantly, this is primarily a win for its Global Security Initiative (GSI) and security through cooperation and development mantra. The agreement demonstrates the GSI’s effectiveness as a crucial paradigm shift in experts’ conventional perception of the initiative as a reflection of typical Chinese jargon, theocratic opaqueness, and rigidity. It has more to do with attaching meaningful actions to the initiative that would give it conceptual meaning and considerable diplomatic weight.

It is also not a coincidence that Saudi Arabia and Iran’s domestic pressures simultaneously align with China’s Marxist-centric view of development as a road to collective security in its new Global Development Initiative. The agreement buys Riyadh time to diversify its economy away from oil by 2030. Tehran, for its part, faces a multidimensional threat emanating from concerns about the regime’s stability in the wake of unprecedented anti-government protests, Israel’s saber rattling over its nuclear program, and a dire economic situation due to mismanagement and a deadlock in nuclear negotiations.

All of the above made the agreement simply fall into China’s lap. Chinese participation in the talks was never a decisive factor in their success, considering the diplomatic heavy-lifting the Iraqis and Omanis have been doing for a long time already. Nevertheless, the leadership in Beijing saw a low-risk, high-return opportunity and decided to take it.

The deal shows Beijing’s appetite to wade into regional diplomacy as an addition to its economic weight. But it should not be seen as a historic shift in China’s strategic approach to the region. Rather, it is diplomatic, substance-free muscle flexing in the face of the United States.

Nonetheless, China’s successful mediation puts unprecedented pressure on the US alliance-building strategy. It could be seen as one step further in China’s push to reduce US influence on Gulf policies and decision-making.

Instead of focusing on what China did to achieve the Saudi-Iran de-escalation, observers should look into what it did not do. Beijing avoided three things that would otherwise deem this agreement a major threat to US interests.

First, China did not actively challenge the US’s status as the sole security provider or undermine its interests. Based on conventional wisdom in Washington, regional peace—especially between Saudi Arabia and Iran—is a crucial precursor for regional stability in the Gulf, which is aligned with US strategic interests. Therefore, China has indirectly—and probably unintentionally—advanced US preferences by maintaining its alignment with the current regional order.

Second, China didn’t use the deal to indirectly fill Iran’s coffers, reflecting China’s continued compliance with US and United Nations sanctions.

Third, Beijing, Riyadh, and Tehran did not lend US adversaries, such as Russia, a free victory vis-à-vis the US by involving them as additional mediators. Had this happened, it would’ve been seen as a regional earthquake and a dramatic change from the Gulf’s historical alliance with the US towards a new Chinese/Russian-centric world order.

The agreement parallels a much harder Chinese push to mediate a de-escalation agreement in Ukraine; China put forth a twelve-point position paper for peace in Ukraine on February 24. On March 20, Xi made his first visit to Moscow since the invasion to meet with President Vladimir Putin and speak virtually to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to formalize the agreement. China is also seen as a crucial partner in any future resuscitation of negotiations on reviving the nuclear deal with Iran.

But all of China’s diplomatic forays have one thing in common: they are interest-centric and do not challenge the US-led West’s interests. Although China’s bilateral relations with the US are at a low point, the specific characteristics of its mediation efforts in the Middle East and Europe show that Beijing is not yet ready to confront the US head-on or jeopardize its interests.

In addition to Washington’s interests-related benefits, China’s increasing involvement in geopolitical conflict mediation presents a window of opportunity to test its vigilance, commitment to forging long-term peace deals, and ability to foot the bill. The Saudi -Iran statement, in particular, shows that its current mediation style, so far, means that China is willing to jump on opportunities and reap diplomatic benefits but not yet ready to bear the cost.

The Joe Biden administration should see China’s mediation as an opportunity, not a threat. It should look into ways to test Beijing’s strategic intentions instead of deliberately belittling those efforts and taking a defensive approach that reveals, more than anything else, unease and puzzlement within the administration. The United States should also intensify its engagement with its Gulf partners and show more understanding of their concerns regarding the US’s long-term commitment to regional security and Gulf interests. China has just scored a crucial goal, but the remaining additional time is more than enough for Washington to make a comeback.

Ahmed Aboudouh is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter: @AAboudouh.

Further reading

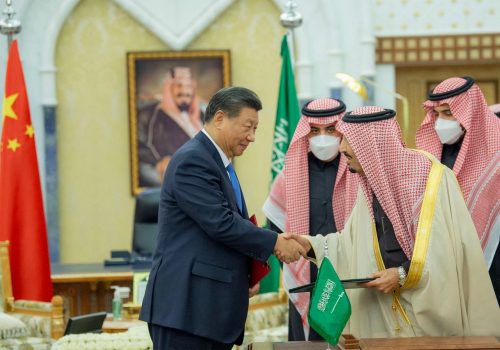

Thu, Nov 10, 2022

How OPEC+ oil cuts accelerate China’s push for multipolarity in the Middle East

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

The OPEC+ decision to cut oil production creates momentum and encourages China to accelerate the exploitation of the multipolar moment rising in the Middle East.

Fri, Mar 10, 2023

Experts react: Iran and Saudi Arabia just agreed to restore relations, with help from China. Here’s what that means for the Middle East and the world.

New Atlanticist By

Long-standing regional adversaries just made a big announcement: They will reestablish diplomatic relations in a deal brokered by China. Atlantic Council experts share their insights on the announcement.

Thu, Dec 15, 2022

No, Xi’s visit to Riyadh wasn’t because of bad US-Saudi relations. It’s about much more.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Given the bad state of US-Saudi relations, it is natural to see Xi’s visit in the context of geopolitical competition between Washington and Beijing, but that framework misses the bigger picture.

Image: Wang Yi, a member of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and director of the Office of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission attends a meeting with Secretary of Iran's Supreme National Security Council Ali Shamkhani and Minister of State and national security adviser of Saudi Arabia Musaad bin Mohammed Al Aiban in Beijing, China March 10, 2023. China Daily via REUTERS