In the wake of new attacks on US troops in Iraq, the administration was reassessing its strategy in Iraq. Then came the coronavirus.

The number of violent attacks on US, Iraqi, and international troops and civilians by Iran-directed paramilitary groups in Iraq has escalated in the past two weeks at an alarming rate. Whether this uptick is a sign of the Iranian regime’s death throes or a considered strategy, Tehran is betting that the world is too consumed with managing a pandemic to hold them accountable—and that the US administration is unwilling to stay the course in Iraq because it is too gun shy in an election year and too financially strapped by the coming burden of US unemployment. The implications of a global pandemic make that a risky bet.

While it is true that the Trump administration’s Iraq policy is largely a corollary of its Iran policy, the US government pursues several objectives in Iraq that are distinct. The first, based on the president’s campaign promise, is to bring US troops home. Other interests include consolidating counterterrorism gains, maintaining a partnership with Iraqi security forces that enables future interoperability, keeping Iraqi energy flowing to the global market, and stabilizing the Iraqi economy to create openings for US companies.

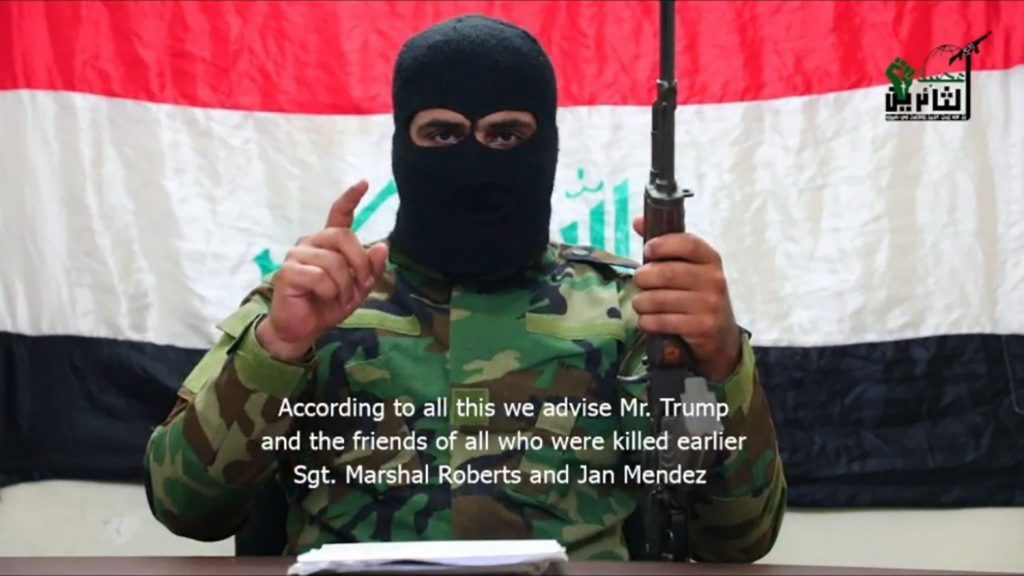

The continued presence of US forces and civilians in Iraq, at the invitation of the Iraqi government, has been a pillar of the strategy to achieve all but the first objective. But a few variables have changed on the ground this month that are causing career officials and senior advisors to the US president to regroup, reset, and reassess how to best pursue US objectives. The first is the geopolitical earthquake caused by the coronavirus. The Iraqi population has not yet embraced the idea of social distancing and the US military understandably wants to reduce exposure by troops housed in closed quarters. The second is the emergence of a group named Usabat al-Thaireen, or League of Revolutionaries, which the US Defense Department believes to be a rebranding of previously designated groups and individuals, vowing to push the United States out of Iraq in two recent trash-talking videos. While the Defense Department has not confirmed which Popular Mobilization Unit (PMU) in Iraq is responsible for each of the mid-March rocket attacks on Americans, this new group claims at least two of them.

A third shift on the ground is the hesitancy of the Iraqi security force charged with protecting the US embassy in Baghdad to do their job. They allowed angry protestors to breach the embassy grounds in January and have made it clear they are not interested in being caught in a fire fight between Kata’eb Hezbollah and the US military.

The fourth shift on the ground is a Kata’eb Hezbollah statement issued a week and a half ago calling for Iraqi militias aligned with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps to work together to oust the US from Iraq.

In light of these shifts and the administration’s conclusion that action is required in the very near term, the US military has four options in Iraq.

The first option is to maintain the status quo and hunker down. This would include prolonging the pause in Iraqi Security Force training and transitioning to NATO the workload palatable to its members. In this scenario the United States could hand over additional bases to Iraqi partner forces and limit troop movement to reduce US visibility and targetability. It could sustain relationships with the Counter Terrorism Service and the Iraqi Security Forces on an officer-to-officer level because they will be important in the future.

A second option is a drawdown that would end Operation Inherent Resolve. Taking this course would result in the withdrawal of conventional forces and trainers, leaving only a specialized unit in place to conduct targeted strikes against groups that carry out attacks against US interests and allies. Shi’a militia groups like Kata’eb Hezbollah, Harakat Al Nujaba, and Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq should know that will include them.

A third option is a smackdown. This involves launching decisive strikes against the Popular Mobilization Units responsible for attacks on the US presence. Once complete, popular outrage would pressure the Iraqi Parliament to order the United States out. The United States would then respect the revocation of the invitation to be present in the country and withdraw. When ISIS resurges and the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps-aligned Popular Mobilization Units start to control the country like Colombian cartels, the blame will fall on the Iraqi Parliament that ordered the eviction.

A final possibility is a hybrid approach combining a phasedown with a smackdown. In this scenario, the United States would gradually pull back troops and trainers. When Americans are safely outside the reach of immediate retaliation, they would go full guns blazing on the Popular Mobilization Units responsible for the loss of American life and the stream of attack planning. Once complete, the Defense Department would immediately announce the end of Operation Inherent Resolve and drop the mic.

None of these are optimal. While options one and two do not appear to be as aggressive as options three and four, the expected continuation of attacks on Americans by Shi’a militia groups means we will wind up at three or four eventually. Option three results in a war in Iraq between interests that do not represent most Iraqis. Option four could lead to attacks on US citizens, allies, or interests outside of Iraq.

All of these response options stop short of strikes inside Iran or even targeting Iranians in Iraq. But the United States will closely monitor Iran’s actions in the aftermath of implementing the option chosen. If Iran is focused domestically on pressures created by the coronavirus and chooses not to mobilize another round of Iraqi proxy militia attacks on US personnel, it could end the cycle of escalation. However, if Tehran elects to expend resources supporting renewed strikes, it should understand that the coronavirus is reconfiguring strategic equations in the United States in real time.

The one variable that the regime in Tehran may not have considered is this: their assumption that US President Donald J. Trump is loath to start a war with Iran is based on conditions that pre-date coronavirus. With US unemployment skyrocketing, the prospect of ramping up military engagement begins to look like an economic stimulus package and federal jobs program.

This financial argument will have to be balanced against the reality that a more robust kinetic conflict with Iran would inevitably include disruption to crude oil flows through the Strait of Hormuz. According to experts at Rapidan Energy Group, a Hormuz disruption would likely last longer than conventional wisdom believes, for many weeks or longer.

A debate about this will work its way through hallways in Washington. Gulf watchers should recognize that COVID-19 has changed the rules of the game. In Iran, where regime survival is the primary objective, the virus is making them reckless. In the United States, where objectives assume a US economy that can underwrite their pursuit, the virus is making past redlines irrelevant.

Kirsten Fontenrose is director of the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council. She previously served in the Trump administration as senior director for Gulf Affairs at the National Security Council.

Further reading:

Image: Members of Iraqi security forces are seen at a civilian airport under construction which, according to Iraqi religious authorities, was hit by a U.S. air strike, in the holy Shi'ite city of Kerbala, Iraq March 13, 2020. REUTERS/Alaa al-Marjani