Why Morocco will not cut ties with Israel

Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal, from the luxury of his exile in Qatar, sparked public anger and controversy by addressing the Moroccan people on November 19 in a video urging them to sever ties with Israel and expel its representative in Rabat amid the ongoing Israel-Hamas war. “Morocco can correct its mistake and perform a duty,” Meshaal stated, calling on citizens to take to the streets in a virtual message during a political rally organized by Morocco’s Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD). Furious Moroccans took to social media to decry the speech as a breach of the kingdom’s sovereignty and an attempt to interfere in its domestic affairs. This incident and the considerable pro-Palestine demonstrations in Morocco in recent weeks have raised an important question: Will mounting pro-Palestinian sentiment pressure Moroccan leadership to reverse the December 2020 normalization agreement with Israel? The short answer is no.

Many Moroccans were shaken by the flow of footage depicting the dire humanitarian situation in Gaza in the aftermath of the October 7 terrorist attacks. Akin to many Arab and global capitals, tens of thousands of citizens have marched in solidarity with the Palestinian people in recent weeks. There are undeniably long-standing affinities between many Moroccans and Palestinians today due to religious, linguistic, and cultural similarities, notwithstanding their geographical distance and often divergent political trajectories.

Bilateral relations might traverse a period of malaise . . . but it is highly unlikely that the kingdom will pull back from its commitments with the United States and Israel.

These protests have led some foreign commentators to proclaim that normalization is in peril. What many such commentators get wrong, however, is that these demonstrations are not happening against the wishes of the country’s leadership and are not perceived as pressure points within Moroccan political spheres. On the contrary, this social movement in support of Palestinians is organized with the state’s blessing. The government provides logistical and security arrangements for demonstrators every weekend, and it seems to view the marches as an expression of indisputable civil rights. It also has clearly formulated a position on the conflict that is in tune with public demands, calling for de-escalation, access to humanitarian aid, and the protection of civilians in line with international law.

Morocco, however, has no intention of revoking the normalization agreement it signed with Israel. Bilateral relations might traverse a period of malaise, and certain public-facing projects might even be frozen until the next Israeli government takes power, but it is highly unlikely that the kingdom will pull back from its commitments with the United States and Israel. This was apparent from Rabat’s veto, together with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan, Mauritania, Djibouti, Jordan, and Egypt, on November 11 that blocked a proposal to cut ties with Israel at the Arab League summit in Riyadh.

Unlike countries that share immediate borders with Israel and have a long history of conflict with it, Morocco has a greater margin to maneuver over its foreign policy. The kingdom has pragmatically shown over the years a quasi-secular approach, decoupling what it considers a religious and brotherly duty to support Palestinians and what it believes can best serve its territorial integrity and economic development agenda. Hence, Rabat often reiterated the importance of involving Palestinians in the Abraham Accords process while it gradually expanded the prospects of its cooperation with Israel. Morocco was even cautious about phrasing its agreement with Israel as a “re-establishment of diplomatic ties” rather than as normalization. The relations between the two countries never graduated from the limited status of reopening their respective liaison offices to having full diplomatic representation, despite Israel recognizing Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara in July—the main pillar of the deal brokered back in 2020 by the Trump administration.

At the same time, several anti-normalization voices are mounting in Morocco, notably influential Islamist and leftist party leaders and elites, such as Abdelilah Benkirane, the former prime minister from the PJD, and Nabila Mounib, the general secretary of the Unified Socialist Party. Many more private citizens are feeling increasingly frustrated at the humanitarian toll of the Israeli military operations in Gaza and have decided to join the boycott, divestment, and sanctions movement or protest groups online and in the streets. Nevertheless, it would be misleading to use a snapshot of one part of society to make a blanket statement about what all nearly forty million Moroccans want or believe.

Over the past few weeks, some commentators and journalists seem to be feeding sensationalism and presenting a misleading image of a country on the brink of serious civil unrest over the Israel-Hamas war. Interestingly enough, while the war on Gaza still dominates headlines, many Moroccans seem more preoccupied with rain scarcity, teacher strikes, reform of the family code, or even the new Pedro Sanchez government in Spain. The country is also linguistically, ethnically, and ideologically diverse. Many Moroccans, for example, chose to stand with Israel in the ongoing conflict using hashtags like “Morocco First” or “Taza before Gaza”—Taza being a small town in Morocco’s northeast. If one were to zoom out from the elites with internet access and social media accounts, one may very well find that a silent majority has no strong opinion on the matter.

Rather than spinning stories about civil unrest in Morocco and reenacting the failed 2011 Arab Spring forecasts about an imminent revolution awaiting the kingdom, it is perhaps better to focus instead on a recent and worrying escalation in Western Sahara. On October 29, the local authorities reported four blasts in civilian areas in the city of Smara, resulting in one dead and three injured. The attacks against civilians, which the separatist Polisario Front later claimed, could represent a kind of spillover of the Israel-Gaza conflict into North Africa, especially with the Front’s insurgents taking advantage of the current international momentum and mimicking Hamas-style speeches and narratives. The Moroccan authorities have since been in constant confrontation with the insurgents, who, for the first time in years, executed an operation in the Moroccan-controlled territories rather than along the Berm sand wall. The German newspaper Die Welt also reported earlier this month on an even more disturbing piece of intelligence, revealing that Iran might be planning an attack on the Israeli liaison office in Rabat using Polisario as a proxy.

These recent developments suggest that the kingdom may tone down its public collaboration with Israel and the United States and continue to criticize the humanitarian situation in Gaza publicly. Yet, it remains improbable to envisage a split with Israel at the security and intelligence levels, as this collaboration is now a matter of national security for a monarchy that’s succeeded in surviving for twelve centuries.

Sarah Zaaimi is the deputy director for communications at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center & Middle East programs where she oversees the Center’s strategic communications, media relations, and social and digital marketing efforts. She previously worked as a journalist and international development professional in Morocco, Egypt, Iraq, and elsewhere in the region.

Further reading

Mon, Nov 13, 2023

On a knife’s edge: How the conflict in Gaza could tip the scales in North Africa

MENASource By Karim Mezran

Western countries should take into consideration the ongoing tensions in North Africa to make their decision-making process regarding the events in Gaza more precise and holistic.

Mon, Oct 9, 2023

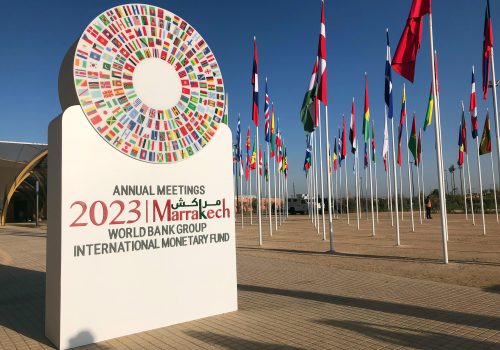

Go behind the scenes as financial leaders gather in Marrakesh for the IMF-World Bank meetings

New Atlanticist By

Atlantic Council experts are on the ground in Morocco to gauge whether global financial leaders can get the world on a trajectory toward ending poverty and attaining sustainable growth.

Tue, Sep 12, 2023

The politics behind Morocco turning down help after the devastating earthquake

New Atlanticist By Sarah Zaaimi

Morocco has allowed search teams to access the disaster areas and deploy their field operations, but it has declined or ignored aid offered by France and Algeria.

Image: Morocco's Foreign Minister Nasser Bourita, waits outside the Kedma Hotel, the location of "The Negev Summit", attended by U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and the Foreign Ministers of Israel, the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco and Egypt in Sde Boker, Israel, March 28, 2022. REUTERS/Amir Cohen