Climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic each disproportionately hurt the world’s poor; together they are a perfect storm of distress and devastation for the most vulnerable members of our global society. The World Bank estimates that in 2021, the number of people living in COVID-induced poverty is 97 million. More than half of the global poor live in South Asia, one of the regions most at risk of climate change. Given the region’s diversity, no one silver bullet exists for every nation and community when it comes to fighting climate change, but, whatever the path chosen, women must be at the center of the solution.

Women comprise the majority of people living in extreme poverty. In South and Central Asia, where an estimated one fifth of the world’s poor women and girls live, systematic factors trap women in the cycle of poverty. Inequitable education, inadequate healthcare, and high risk of exploitation and violence impoverish the lives of women across the region.

Simultaneously, as South Asian economies have grown and caused a movement of men to take jobs both in manufacturing and abroad, women are increasingly involved in agriculture, food production, and water access in South Asia. In Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, and Pakistan, women outnumber men in the agriculture sector. In these countries, 60-98% of the agriculture workforce are female. Women have become the front line against the effects of climate change in their communities. Extreme and unpredictable weather due to climate change continues to affect farming and water access, propelling women to adapt their practices or face economic ruin. Raising the share of women in climate dialogues will create better representation of women’s concerns in climate response, and it is also likely to lead to more effective adaptation strategies.

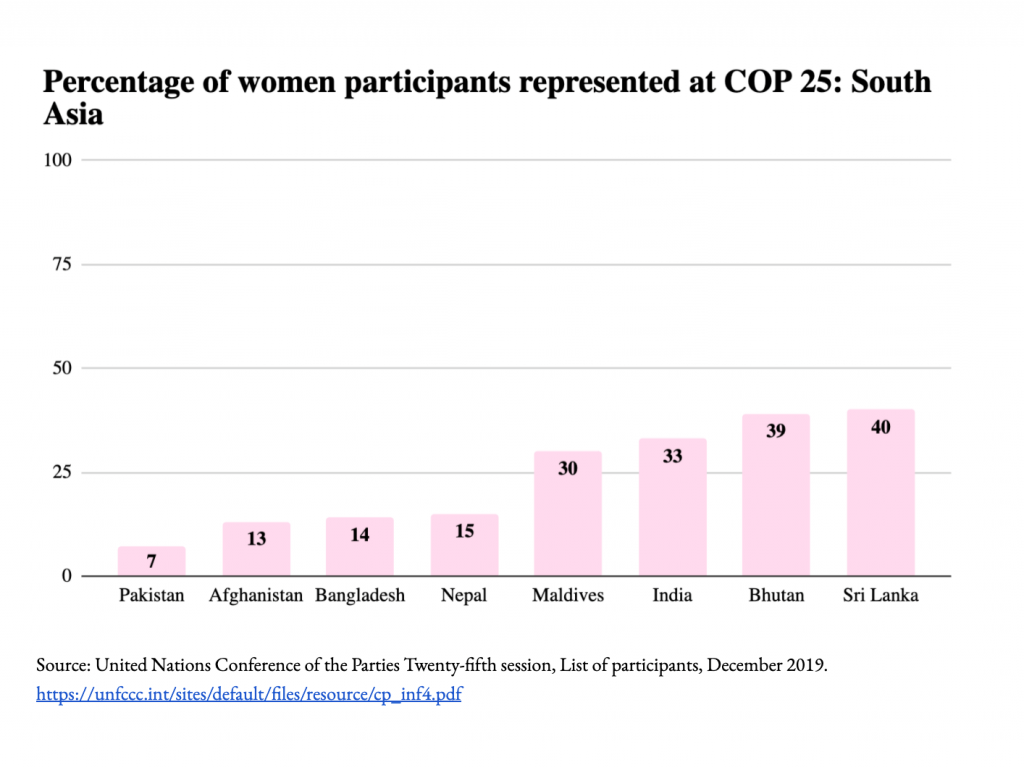

Yet, South Asian women are too often excluded from the decision-making processes that disproportionately affect them. At the 25th Conference of the Parties (COP 25), female representation from South Asia was discouragingly low. Of the 237 participants from South Asia, only 50 were women, accounting for just 21% of the region’s participants. Bhutan and Sri Lanka had the highest female representation, with 39% and 40% respectively. From Pakistan, only one of the fourteen participants was a woman, accounting for a paltry 7% of its delegation.

There are lots of examples around the region of how women are combatting the effects of climate change in their communities. Women have implemented climate-smart farming techniques and innovative solutions that address their realities. To prevent runoff and soil erosion, women constructed embankments; when faced with pest outbreaks, women concocted homemade solutions to rid the crops of their pests. Farming in unforgiving climates has led women to perfect water management techniques, a key to climate-resilient farming. Working together to prevail against the warming climate, women have implemented institutional arrangements to manage common property resources better and have formed women’s self-help groups. Women are adapting to the warming climate, and they are doing it together on the front lines. As they continue to lead by example, it is time for the world to start listening.

Of all 8 countries in South Asia, only Nepal and Bangladesh have implemented Climate Change Gender Action Plans, augmenting their individual National Climate Change Action Plan to identify gender-specific issues in each priority sector. These action plans incorporate gender as a crucial concept in national climate change processes, policy development, decision-making, project development, and implementation.

Following in Nepal’s footsteps, countries should adopt policy directives for establishing quotas that increase women’s participation in agriculture climate action. As a result of these quotas, Nepali women increased their skills, social status and decision-making power. Similarly, Bangladesh has taken action. As part of their Climate Change and Gender Action Plan, they have spearheaded a project to increase the share of female entrepreneurs who have access to innovative technologies to support climate change adaptation. They have also established “Climate Field Schools” for women farmers which provide specialized climate training and networking programs for women.

Furthermore, the cheapest, most cost-effective solution to mitigate climate change is girls’ education; educating girls is more likely to result in lower carbon emissions than urban public transport, renewables, or improved agricultural practices. Higher levels of education lead to lower rates of fertility; lower rates of fertility lead to a more sustainable population, ultimately mitigating human-accelerated climate change. By supporting reproductive health and education programs, governments can take steps to curb overpopulation which will significantly mitigate future CO2 emissions and reverse the trend of increasing poverty in South Asia. Investing in young girls is good climate policy.

The COP26 climate summit is about to start in Glasgow on Sunday. Monetary commitments will be central to the discussion there. Governments must re-examine their climate finance policies to ensure that funds are directed to and advised by those who know the on-the-ground truth, rather than others who will be drawn to invest in climate buzzwords such as renewables and technological saviors. As all eyes turn to climate policy in the coming weeks and months, a visible indicator of success will be how many women are at the table. Gender needs to be incorporated into all national action plans in South Asia. Climate finance should invest in girls’ education and support on the ground realities that South Asian women battle everyday. Women are South Asia’s best asset to fight climate change, and honoring and learning from their knowledge and expertise is our best chance to prevail against this existential challenge.

Megan Goyette is an analyst at the New York Times with an interest in climate change and South Asia. She was formerly a project assistant at the South Asia Center.

Emily Carll is a project assistant with the South Asia Center and a current Fulbright English teaching assistant in Serbia.

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related content

Image: Farmers harvest rice on a field in Lalitpur, Nepal October 26, 2016. REUTERS/Navesh Chitrakar