South Asia midyear pause: Taking stock of 2021

Introduction

By Harris Samad

Though 2021 offers a glimmer of hope that the end of the COVID-19 pandemic is near, South Asia will contend with this wicked killer for far longer than the United States and its allies. In particular, given the region’s strained healthcare systems, geopolitical tensions, and economic slowdowns, it will likely experience the medium- and long-term ramifications of this unprecedented crisis for at least the next decade. Though we can and should be optimistic about the increasing availability of vaccines across South Asia, a parallel effect continues to take hold—particularly in the “big three” states (Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan)—as authoritarian figures and entrenched powers use the pandemic to justify heavy-handedness in suppressing media, free speech, religious diversity, and other pillars of democracy. Moreover, COVID-19 has exacerbated existing socioeconomic inequality across South Asia to the detriment of hundreds of millions of livelihoods. None of these issues are new, but the pandemic has made them far worse.

Intersecting with COVID-19, other crucial issues also confront South Asia in the remainder of 2021. How will the US withdrawal from Afghanistan impact human security, regional stability, and economic prosperity for that beleaguered nation? Will the Biden administration continue to treat Pakistan as a key ally? Can India really be the China counterweight that Washington desires? Will Bangladesh—until recently a leader of economic growth and vibrant democracy in the region—resist creeping authoritarianism? What about the existential threat of climate change that affects the whole of South Asia, but especially countries such as Nepal, in the foothills of the mighty Himalayas, or Sri Lanka and Maldives, a-sea in the vast Indian Ocean? As before, we do not presume to have the answers but hope our analyses provide a framework for understanding South Asia’s prospects in what remains of 2021.

Click here to read the South Asia Center’s 2021 road ahead analysis to explore the broader context of these issues.

Jump to a country:

Afghanistan

By Fahim Ahmad

The decision by US President Joe Biden’s administration and its NATO allies to withdraw all troops from Afghanistan by August 31, 2021, will test the young republic’s sustainability as the Kabul government is already struggling to fend off Taliban insurgents’ aggressive spring offensive with the objective to protect the budding democracy. Attacks on Afghanistan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) and civilians have increased drastically—including targeted killings of minorities and children—making hopes for a durable peace grim and far from reachable. Many fear that gains made in the last twenty years, particularly regarding women’s rights, could be at risk. Afghanistan faces a multitude of challenges including improving the deteriorated security situation across the country, tackling the COVID-19 pandemic, and boosting a struggling economy heavily reliant on foreign aid.

Taliban insurgents do not seek peace: The peace negotiation in Doha between the Taliban insurgents and Afghan government is at a stalemate, with the Afghan side pressing the Taliban delegation to agree to a ceasefire. However, the Taliban group seems to be pursuing an all-out victory and is not adhering to the initial commitments of the Doha agreement with the United States, those being a reduction of violence and agreeing to a political settlement. The current situation reveals that the group is mainly exerting violence as a strategy to gain territorial and political control, which has ultimately led to the Doha deal and the US and NATO withdrawal. To reinvent itself and clean its public image, the group has appeared on international media, promised reforms, and claimed that they are no longer the Taliban of the 1990s; however, such promises are merely used as a manipulative tool to gain international legitimacy and media coverage, ease international sanctions, and gain the ability to travel freely. The somewhat moderate group of Taliban in Doha will continue to persuade the hardliners on the ground to continue their fight by promising that victory is within reach. Any peace negotiation starts with a short-to-long-term ceasefire that helps the process kick-start and run smoothly; however, the Taliban fears that agreeing to a ceasefire would slow the fighting machine on the ground and ultimately cost them the upper hand at the negotiation table. Current efforts will not result in long-term peace since they will merely result in a peace deal rather than a peace process. In reality, only the latter is sustainable.

Creating and supporting militia groups is a flawed policy: The Afghan government is recruiting local militias and supporting former ethnic warlords to fight against Taliban advancement, a move that represents a strategic blunder and only a short-term solution to its security-sector shortcomings. Historically, Afghanistan has not had a pleasant experience with ethnic militias having access to weapons, such as the mujahideen who commenced a bloody civil war after Soviet troops left Afghanistan; and history has shown that rebel groups with ethnic and political affiliations have been manipulated both by domestic and foreign actors for specific motives. The mujahideen, who have enjoyed enormous power in the last twenty years, have consistently undermined the central government when their demands have not been met. This has led to fundamental institutional reforms not taking place, including but not limited to transitional justice, anti-corruption and counter-narcotics efforts, and election reforms. The Kabul administration needs to enlist these “volunteer” military supplements with proper identification to ensure future accountability for their actions and avoid a repeat of history, namely human rights abuses along ethnic lines.

Continued support for Afghan democracy: To turn the page on four decades of war and avoid another military intervention, the United States and its NATO allies should continue to stand with the republic and the current government to preserve the gains made in the last twenty years. Grave risks will persist should Washington not make clear its intentions to support Kabul and back them up with robust assistance.

Grave risks will persist should Washington not make clear its intentions to support Kabul and back them up with robust assistance.

Top Pentagon leaders have warned that terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda may have the potential to regroup and use Afghanistan as a breeding ground to pose a threat to other countries—including the United States—as quickly as two years post-withdrawal. To prevent such a scenario, the ANDSF requires continued military and financial support from the United States and its NATO allies to stop the emergence of terrorist groups. As of January 2021, the total number of ANDSF personnel was at 307,000 and the US Congress has approved a little over $3 billion to support the forces for 2021, its lowest appropriation to fund the force since 2008 The ANDSF will undoubtedly rely on continued military aid beyond 2024, deeming security assistance crucial to prevent a full-scale civil war. Post-US withdrawal, the ANDSF will be responsible for all military operations. For it to be able to sustain itself and maintain security, there is a dire need for funding and modern military equipment. The United States and NATO should continue to train and equip the Afghan military, including by upgrading its underdeveloped air force. Moreover, the international community should use foreign aid as leverage to encourage anti-corruption and other reform efforts within the security sector.

Despite the delicate situation, the Biden administration—if it plays its cards right for the remainder of the year—can strengthen the military and political partnership with the Afghan government to achieve strategic goals including national security priorities and promoting and strengthening republicanism and democracy abroad.

Economic growth: The COVID-19 pandemic coupled with political unrest hit the Afghan economy hard in 2020, resulting in decreased trade and decreased revenue. The unemployment rate was reported to be 11.73 percent in 2020 compared with 10.98 percent in 2019; however, Afghanistan is expected to see an increase in gross domestic product (GDP) from 3 percent in 2021 to 4 percent in 2022. The question remains whether the country will be able to sustain and even exponentially increase growth. Afghanistan is a landlocked country that relies heavily on imports and has not diversified its products. With its current rate of growth and lack of diversification, the economy will not be able to generate revenue and ensure long-term economic sustainability.

Inflation is forecast to be 5 percent in 2021 and 4 percent in 2022, according to the Asian Development Bank, and a slight disruption or delay in imports can cause food prices to spike even further in the market, making it difficult for consumers to adjust to increased prices, and further pushing those vulnerable into poverty. The balance of trade is currently a negative value of more than $5 billion, resulting in reduced wages for domestic workers and an overall reduction in national savings. Import-oriented economies tend to face challenges including high inflation rates and reduced consumer buying power. Hence, the country should focus on diversifying its economy including by investing in human capital, which would result in a higher employment rate and a reduction in poverty. Moreover, corruption is a major issue impeding economic growth. Afghanistan should make an ample effort to tackle corruption as part of international best practices and strategies.

Bangladesh

By Ayra Khan

Fifty years after independence, Bangladesh has caught up to its South Asian neighbors in terms of economic indicators, such as per capita income and GDP growth, and social indicators. Challenges persist as it transitions from an agriculture-based economy to an industrial and service-oriented one. The COVID-19 global pandemic has exacerbated pressure on healthcare facilities and exposed social inequalities. Likewise, climate change must also be confronted, and Dhaka must navigate changing regional political dynamics adroitly to avoid setbacks.

Vaccines—diplomatic opportunity or a path toward conflict? Early in 2021, Bangladesh had begun to show signs of recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic with reduced restrictions and increased trade. However, as of June 2021, a second wave has led daily infections to reach new highs, with cases rising sharply.

In response to the continuously developing COVID-19 situation, obtaining vaccines is high on Bangladesh’s agenda. Though the country promised to purchase thirty million vaccine doses in a deal with the Serum Institute of India in November 2020 and received promises to get vaccines from other wealthy countries, the severity of India’s COVID-19 crisis and vaccine export ban, coupled with slow delivery and broken pledges, left Bangladesh unable to procure enough vaccines. As a result, Bangladesh has sought new suppliers to meet its demand, including China and the United States. Interestingly, these developments in vaccine acquisition occur behind a tense political backdrop for Bangladesh. China has recently begun to expand its scope in the region, with vaccines offering a unique opportunity to extend a helping hand. Similarly, China had expressed concern over the possibility of Bangladesh joining the Quad, a strategic partnership among the United States, Australia, India, and Japan. As Bangladesh’s economic outlook rises, its role as a strategic player is also emerging. Will vaccine diplomacy enable its ambitions by providing life-saving shots or thwart those ambitions by rendering the country a pawn sacrificed in great power politics?

Domestic shortcomings: What can Bangladesh do next? COVID-19’s political and social implications have extended beyond foreign relations. The pandemic raises troubling questions about the state of the health system and its ability to serve underprivileged groups. Healthcare is a significantly underfunded sector, with only “5.14 percent of the total [fiscal year 2021] budget,” or “less than 1 percent of GDP,” allocated to it. The ongoing pandemic has exposed the need for crisis relief measures, adequate healthcare, and inclusive health support, which together require far greater outlays of expenditure.

The pandemic has also provided a revealing glimpse into the mechanisms of Bangladeshi institutions. In response to concerns raised about “disparities in healthcare access,” the government “silenced healthcare workers,” and government employees. Such actions add to concerns raised by organizations such as Human Rights Watch about growing censorship enabled by new laws such as the Digital Security Act of Bangladesh. However, in spite of the devastation caused by COVID-19 and a return to a stringent lockdown, there are reasons for optimism for Bangladesh’s future. Though Bangladesh has fully vaccinated less than 3 percent of its population, it has approved seven vaccines and resumed mass vaccination in July. Bangladesh has also created a new digital platform to coordinate and enable vaccine access. Before the second wave of coronavirus, there had been a positive rebound within various industries. With the rising availability of vaccines, hope for a return to normalcy grows. But as is true worldwide, there is also the realization that the previous normal did not work for all. For marginalized groups who were and continue to be disproportionately affected by the pandemic, such as women, particularly those employed by export-based industries, or refugees in Cox’s Bazar, the recovery has been riddled with inequality. For example, income distribution remains more unequal for low-income families, and women continue to lag in reaching pre-COVID employment levels. Overall, new policies and efforts must be inclusive of underprivileged groups to create meaningful and long-lasting recovery.

The [pre-pandemic] normal did not work for all… . New policies and efforts must be inclusive of underprivileged groups to create meaningful and long-lasting recovery.

Climate change: What is next? Bangladesh ranks sixth on the Global Climate Risk Index and continues to be among the most vulnerable countries to climate change due to its physical topography and social factors, including poverty and population density. Cyclone Yaas, which caused intense damage to the area, is the most recent in a long list of climate-related disasters to afflict the country. While Bangladesh’s crisis response to climate-related incidents has improved over the years, much remains to be done to support “resilient coastal communities.” Aside from more technical efforts such as shelters and disaster management programs, Bangladesh must redesign its climate response to prepare for long-term change. Bangladesh is a member of various global initiatives, including Partnering for Green Growth and the Global Goals 2030 (P4G) and the Leaders’ Summit on Climate, the latter convened by the United States in the spring of 2021. However, beyond such programs, Bangladesh must take concrete steps to contribute to global sustainability measures. These steps can include reducing its carbon footprint by decreasing the production of fast fashion. Moving away from such practices would help mitigate long-term ecological damage and reduce the threatening work conditions in this industry. Likewise, the scope for a blue, resilient economy is ever-present and becoming more evident. By supporting efforts to reduce the impacts of climate change and encourage sustainability, Bangladesh can support its growing economy as well as marginalized groups that are more vulnerable to climate shocks including the Rohingya refugees, who are disproportionately affected by monsoon-related disasters and the shortage of facilities, and women.

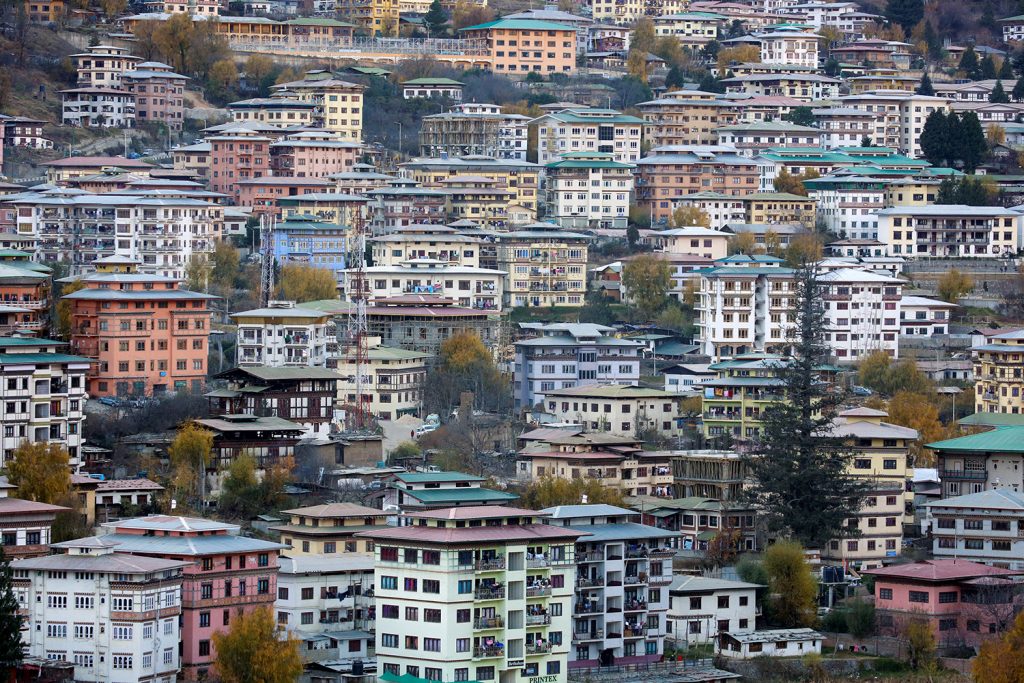

Bhutan

By Emily Carll

To date, just two people have died of COVID-19 in Bhutan. That said, the fact that Bhutan sits in between two countries that have suffered major COVID-19 outbreaks illustrates a highly delicate situation. Moreover, its reliance on regional hegemons to secure access to vaccines has put it in a precarious position. The struggles and effects of COVID-19 are far from over in Bhutan. Meanwhile, establishing itself on the international stage and furthering global partnerships will be a challenging yet critical opportunity. With continued restrictions and isolation due to the pandemic, Bhutan will need to be creative in its diplomacy but use its newfound inclusion and leadership roles to be a driving voice on key issues such as climate change. Going into 2022 Bhutan may also be forced to end its strategic silence to manage Chinese expansionism depending on the progress of talks between the countries to settle border disputes. Finally, it will be important to see how Bhutan will navigate its climate vulnerability after learning lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Managing COVID-19: Going forward in 2021, Bhutan will be at the whims of geopolitical giants for fair vaccine distribution. As studies continue to lower the eligible vaccination age bracket, and the Delta variant continues to permeate its southern border, Bhutan will need vaccines for younger individuals. India’s Vaccine Maitri initiative remains suspended with no resumption in sight due to the continued crisis there, while Bhutan barely avoided a situation that could have led to the collapse of its healthcare system. After obtaining second-dose vaccines from Denmark—with only two weeks remaining before the efficacy of the vaccine expired for the more than 93 percent of Bhutan’s eligible adults who had already gotten their first shots—Bhutan will have to ensure that it has reliable partners going forward.

Bhutan will need to be creative in its diplomacy but use its newfound inclusion and leadership roles to be a driving voice on key issues such as climate change

Growing international presence: Now included in platforms such as the P4G Summit and holding the presidency of the seventy-fourth World Health Assembly, Bhutan has the opportunity to raise awareness of issues that disproportionately impact smaller countries. Bhutan can seriously engage multilateral and bilateral fora on climate change discussions and solutions and should consider doing so before it is too late. In the first half of 2021, Bhutan used its international contacts to address this issue, signing a memorandum of understanding for cooperation on climate change and waste management with India and participating in the P4G Summit where world leaders addressed climate change and progress toward the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. Seeking to increase its international presence and build partnerships with countries in the region despite the pandemic, Bhutan will need to emerge from isolation and further engage the greater region and world. In June, Bhutan’s National Assembly adopted a preferential trade agreement between Bhutan and Bangladesh, a necessary step to begin integrating its economy into the region. Yet to successfully engage the greater region and world, Bhutan could use both its vaccination needs and the potential of the remote-work world to engage in creative diplomacy and forge partnerships with countries it may not otherwise engage.

Managing Chinese expansionism: While Thimphu has avoided aggravating its larger neighbor—particularly when Bhutan needed Chinese aid to control the pandemic—the country can maintain its strategic silence for only so long before current tensions come to a head. China is slowly pushing boundaries and limits along the China-Bhutan border, which it claims were never delineated. In April, China and Bhutan agreed to resume talks to come to a peace agreement, but China has allegedly taken things into its own hands and has started building infrastructure and buildings in rural Bhutan, a land-grabbing strategy similar to what it is doing in the South China Sea. While there has not yet been a direct conflict and exchange of gunfire, such as has happened in the China-India border conflict, the China-Bhutan border dispute is worth keeping an eye on.

Addressing climate change post-pandemic: Coming out of the pandemic, Bhutan is more vulnerable than ever to climate change. If the international community reverts to the normal actionless talks on climate change, Bhutan stands to be devastated by its effects. Its economy is reliant on climate-sensitive sectors including hydropower, agriculture, and environmental tourism, necessitating the need for climate resilience. Bhutan must invest in climate resilience and collaborate with regional partners on education and training surrounding natural disaster response while continuing to advocate in forums such as the P4G, the United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties, and others about the impacts of climate change and how to build climate resilience. Bhutan disproportionately feels the effects of climate change as landslides and flash floods have become a common occurrence, especially due to glacial melting and glacial lake outburst floods. It will be important to see if Bhutan and the international community will translate lessons learned about the importance of preparedness and resilience from the COVID-19 pandemic to mitigate climate vulnerability.

India

By Capucine Querenet

For India’s massive 1.3 billion population, 2021 offers no respite from COVID-19. With over thirty-one million confirmed cases, overwhelmed health infrastructures, and a crumbling democracy, the country once considered an economic powerhouse positioned to overtake China is faltering with yet more formidable challenges ahead. Post-pandemic reconstruction will require a concerted and collective effort by domestic and international actors to restore India’s vibrant economy, while public tensions over the government’s mishandling of a second coronavirus wave test the country’s political landscape.

A humanitarian crisis: The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s February 2021 declaration of victory in the fight against COVID-19 was premature. Loosened restrictions and public complacency, coupled with a slow government response to highly contagious variants, catalyzed a horrific second wave as infections soared to record the highest single-day figure globally. At the peak of the second wave, India was reporting an average of four hundred thousand cases per day, though evidence of underreporting suggests a much higher case count and death toll than even these gaudy numbers suggest. Overtaxed hospitals, still reeling from the first wave, were brought to their knees by the second wave and even today are forced to turn away patients, some of whom have desperately resorted to the black market, while those lucky enough to secure a bed scramble to find oxygen tanks and COVID-19 medications. Families vie for space at cremation grounds, even erupting into physical fights as emotions run high. Though official numbers as of mid-June show signs of easing—Delhi in fact lifted restrictions on manufacturing and construction in late May—the virus remains active and the government’s slow vaccination drive leaves room for variants to develop. Countering a third wave requires swift government action; however, many argue the latter has yet to materialize.

Critics of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s response largely cite his dismissal of expert warnings and blatant disregard of reality in favor of misleading optimism. As hospitals and crematoriums struggled to keep pace, critics argue that the prime minister showed greater concern for the future of his political fortunes than the health of the Indian population by allowing maskless religious and political gatherings and avoiding announcing the restrictions required to stem the rampaging virus. Such decisions worsened the crisis, which is predicted to knock off 2.8 percentage points from GDP growth in fiscal year 2022 and has pushed news outlets to become increasingly critical of current leadership. While vaccines offer a path forward, shortages, complicated policies, misinformation, and vaccine hesitancy have undermined the government’s vaccination drive with only 7.2 percent of the population fully immunized. Though the government launched a new policy offering free vaccinations to eligible adults, the social and economic impacts of COVID-19 are significant and require a reimagined government response to facilitate post-pandemic reconstruction.

The social and economic impacts of COVID-19 are significant [in India] and require a reimagined government response to facilitate post-pandemic reconstruction.

An erosion of democracy: Separate reports published in May 2021 by Freedom House and the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) measuring the state of democracy downgraded India in rankings to a “flawed democracy.” V-Dem even labeled India an “electoral autocracy,” citing increased pressures on human rights groups, curbs on media freedoms, and attacks on Muslims as the primary indicators of eroded political and civil liberties in the country.

Censorship efforts by the national government and its state allies are increasingly routine with laws on sedition, defamation, and counterterrorism used widely to silence critics. In early 2021, a farmer protest in Delhi led to dozens of police complaints against farm leaders, journalist arrests, suspensions of Twitter accounts, and loss of electricity, water, and internet. Later, in April, about one hundred Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter posts criticizing Modi’s COVID-19 response were removed at the BJP’s request. Just last year, sixty-seven journalists were arrested, detained, and/or questioned for their work. Siding with the government offers protection and business, while critics face court battles, blackouts, jail, and more. The government’s legislative and regulatory actions against media and civil liberties will have a lasting impact on India’s democratic credentials for years to come.

Maldives

By Ayra Khan

In June, Maldivian Foreign Minister Abdulla Shahid was elected president of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, outperforming his Afghan rival and capping a relatively successful first half of 2021 through which the island nation maintained its reputation as a must-travel destination in spite of the pandemic.

Maldives fights to remain a top travel location, despite the global pandemic: Maldives’ tourism-oriented economy took a severe blow in 2020, losing almost 67.4 percent of its tourists in early 2020, creating a vacuum in growth resulting from a loss of jobs and foreign exchange receipts. In July 2020, however, Maldives saw a resurgence, with tourist numbers surpassing predicted levels. These prospects continued well into 2021, an unexpected success credited to various factors, including its unique geographical advantages, well-adapted tourism infrastructure, and strict health requirements. Creative efforts, such as the 3V program, aimed to attract tourists looking to “visit, vaccinate, [and] vacation,” were also introduced in early 2021. However, despite its successes, Maldives has been placed in a difficult position as neighboring countries such as India have seen a surge in coronavirus infections. As a result, Maldives was forced to suspend tourism from South Asian countries, which is worrisome since this sector contributes to over 28 percent of the nation’s GDP. However, Maldives’ COVID–related outlook remains positive with continuously falling case numbers and a steady rate of vaccination (Maldives has enough doses to vaccinate around 54 percent of its population). A reopening of borders seems possible as early as July 2021, with restrictions already being reduced.

As climate concerns rise, does Maldives have the chance to shine? Climate change poses an existential challenge for Maldives. Raised by various leaders at multiple platforms, Maldives’ stance on sustainability remains positive and firm. Shahid has promised to encourage green, sustainable growth and also tackle the issue of climate change. This is of growing concern as rising sea levels, in particular, place Maldives in a highly vulnerable position. To respond to the looming threat, in collaboration with the Asian Development Bank, Maldives has established a comprehensive road map for its energy sector for 2020-2030. This plan underscores the critical role renewable energy investment has played and will continue to play in sustaining long-term growth in the country. In particular, solar, wind, tidal, and biomass energy sources remain unexplored and undercultivated, offering Maldives a unique opportunity to showcase climate-oriented innovation. Likewise, Maldives has a novel opportunity to lead the world in becoming a “blue economy.” Overall, climate change efforts offer a unique chance for Maldives to play a leadership role in enabling global collaboration with the help of investors, knowledge sharing, and interest from various stakeholders.

Climate change efforts offer a unique chance for Maldives to play a leadership role in enabling global collaboration with the help of investors, knowledge sharing, and interest from various stakeholders.

Political uncertainty and the pursuit of justice: Maldives is a young and learning democracy, having chosen its first freely elected president only in 2008. While over a decade has passed, the reality remains that Maldives is still discovering its path to creating a free, just, and democratic nation. This year has thus far been concerning amid recent political unravelings, including the attack in May on former President Mohamed Nasheed, attributed to religious extremism and political differences. Furthermore, Maldives scores relatively low on political freedom, scoring only 40 out of 100 points on Freedom House’s rankings in 2021. Areas for improvement include stronger measures against corruption and improved civil liberties, including freedom of the press and freedom of religion. A bright spot is Maldives’ introduction of the Transitional Justice Act and institution of the Office of Ombudsperson for Transitional Justice. The act is described as aiming to “[sanction] investigations into past wrongdoings by state authorities, heads of agencies, or individuals in power, which resulted in human rights violations.” While this is a step in the right direction, critics point out the disconnect between the intended and actual outcomes of the bill. In particular, they raise questions regarding the adequate enforcement of the bill, the ability to ensure accountability despite massive power imbalances, and the proper protection of the privacy and safety of victims. Will this bill serve the people who have suffered, or will it only act on a performative level? The answer will set the tone for the future of Maldives’ fabric as a nation and its relationships with its citizens.

Nepal

By Harris Samad, Capucine Querenet, and Areeba Atique

This year offers Nepal little reassurance as the country dives headfirst into a severe political and healthcare crisis catalyzed by a second coronavirus wave. Unprepared leadership has left overwhelmed hospitals to fend for themselves as medical supplies, beds, and healthcare workers run scarce, while pandemic-related disruptions disproportionately affect the poor and threaten to push more below the national poverty line. Women’s safety, too, remains at stake with new legislative frameworks that offer more harm than help and highlight the country’s recession of human rights. Overall, Nepal paints a bleak picture for the remainder of 2021 on intersectional issues related to corruption, coercion, and its COVID-19 pandemic response.

A healthcare catastrophe: Like much of South Asia, Nepal’s already under-resourced public health system has been further debilitated by COVID-19. With fewer than two thousand intensive care unit beds and six hundred ventilators for a population of thirty million, a humanitarian crisis is unfolding with far-ranging political and economic repercussions mirroring those of Nepal’s 2015 post-disaster recovery. To date, institutional incompetence and dysfunctional governance have sidelined marginalized communities while medical supply shortages exacerbate death tolls. Though medical supplies from China recently arrived, extra resources will prove futile without adequate government response or a strong vaccination campaign, both of which seem unlikely.

In late February, Minister for Health and Population Hridayesh Tripathi expressed optimism about receiving Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines from the Serum Institute of India, though this promise was short-lived. A spat between the Nepali government and Hukam Distribution and Logistics Private Limited—the agency in charge of supplying vaccines—leaves only 2.5 percent of the population fully immunized and threatens a third wave worse than India’s second surge. Mitigating this requires states to work collaboratively in supporting global mechanisms such as COVAX, yet whether such a policy materializes is uncertain and will be a crucial area to watch moving forward in Nepal.

Gender-based rampage: Recent legislation depriving women of self-determination and freedom garnered significant backlash for its skewed and myopic priorities that highlight leadership’s paternalistic views. Under the amendment, women under the age of forty must obtain approval from families and local wards to travel abroad and cannot seek employment outside the country. Though this is said to be intended to mitigate human trafficking and violence toward women and girls, it is a distinct example of victim-blaming and discriminatory legislation. The proposal objectifies women—first, by denying their autonomy in lieu of empowerment and capacity-building efforts; second, by doing so without female decision-making authority; and third, by regulating women rather than associated agencies and institutions.

Given that vulnerable populations have systematically been sidelined throughout the pandemic, repealing the current proposal and implementing smarter strategies is imperative to ensure women’s and girls’ safety. The Nepali government should work collectively with other nations to enact protection programs and should better regulate recruitment agencies to prevent gender-based abuses. Critically, however, many more women are needed at the decision-making level.

Unnecessary political maneuvers from both the formerly ruling Nepal Communist Party and its opposition overshadowed efforts necessary to combat COVID-19 and projected a long, tedious road to recovery.

Political turmoil after Parliament’s disbandment: Tandem to Nepal’s health and human rights crises, its troublesome political landscape does not inspire confidence; however, fresh leadership may open a new chapter. Former Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli’s assaults on the country’s constitution and democratic endeavors led to his demise when the Supreme Court ousted Oli in mid-July to instate President of the Nepali Congress Sher Bahadur Deuba for an eighteen-month position—his fifth stint in leadership. Though Deuba’s appointment is a welcome change for many, fissures are already emerging and the new prime minister’s history of ill governance practices may indicate future failure to end Nepal’s political chaos. As the country grapples with COVID-19 repercussions, notably a faltering economy and a public-health crisis, decisive and efficient leadership tending to the population’s needs rather than those of political parties is critical. But thus far, unnecessary political maneuvers from both the formerly ruling Nepal Communist Party and its opposition overshadowed efforts necessary to combat COVID-19 and projected a long, tedious road to recovery. Whether Deuba will navigate the current crisis appropriately and smartly remains to be seen; however, continued political infighting and inefficient governance bode ill for the country’s future.

Pakistan

By Kaveri Sarkar

This year presents a multitude of challenges for cash-strapped Pakistan. The economy remains in trouble, domestic political instability continues, vaccination centers face shortages, the situation in neighboring Afghanistan crumbles further, and Islamabad’s geoeconomic ambitions remain far from being realized. The remainder of 2021 will require Pakistan to concentrate its efforts to tackle the ongoing third and a possible fourth wave of the pandemic, articulate a cohesive economic strategy, and engage its neighbors responsibly.

The US military withdrawal from Afghanistan puts the spotlight on Pakistan: With Pakistan descending lower on Washington’s priority list in 2021, the US withdrawal from Afghanistan further threatens to unmoor Pakistan’s relevance to the United States. The imminent military withdrawal also brings Pakistan’s approach to Afghanistan into the limelight on the international stage. A regional consensus for Afghan peace is imperative yet currently lacking, and Pakistan stands to lose in many ways if the Taliban regains power. While the Pakistani leadership has pledged its support for and commitment to the intra-Afghan peace negotiations—powered by Prime Minister Imran Khan’s visit to Kabul last November—Islamabad will need to substantiate this rhetorical commitment with meaningful action. In 2021, it is in Pakistan’s national interests to leverage its long-standing ties with the Taliban to help negotiate a peace deal, along with weeding out Taliban strongholds within its own borders. If it does not, it stands to suffer from an influx of Afghan refugees, increased Taliban influence on militants housed within its own borders, and the evaporation of its economic and regional connectivity goals. Unfortunately for Pakistan’s international image, the recent abduction of the Afghan Ambassador’s daughter in Islamabad followed by Pakistan’s denial of the incident has led both countries to retract their diplomats—thereby exposing cracks in the already tense Pakistan-Afghanistan relationship—and conjured a diplomatic disaster for Islamabad. While marring the country’s dismal reputation regarding internal security, this abduction and the murder of a former Pakistani diplomat’s daughter also raise questions on the safety of women and gender-based violence more broadly.

Geoeconomic ambitions or delusions? In 2021, Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi and Chief of Army Staff General Qamar Javed Bajwa elucidated Pakistan’s aim to move from a geopolitical state to a geoeconomic one, a goal central to the country’s 2025 vision. This shift in goals is positive, but there are mounting concerns about Islamabad’s ability to realize these geoeconomic ambitions.

Pakistan’s debt to China now amounts to $24.7 billion, a phenomenon that Western analysts brand “debt-trap diplomacy.” Pakistan has cited waning US interest in Pakistan as having catalyzed Chinese involvement and deepened a seventy-year bilateral friendship; however, several factors deter foreign investment from the United States and other nations to Pakistan. Though it boasts more open foreign direct investment laws, the country’s Financial Action Task Force Grey List rating; incoherent governmental policies such as the TikTok ban, which was issued late last year and later rescinded; and a confused economic policy are unattractive, especially for e-commerce businesses. The recent addition to Amazon’s seller list, however, is a welcome update as it will likely lead to an increase in employment and exports, and make gracious use of the startup ecosystem in Pakistan.

On the other hand, the economic conversation taking place in the country remains limited to gas and power subsidies, lacks creativity and investment in research and development, and struggles to compete with the manufacturing sectors of other developing countries, all while textile and agricultural patronages dominate and inflation cripples the less privileged sectors of society. Adding to these woes, environmental sustainability continues to be the missing piece in Pakistan’s geoeconomic puzzle. Taking stock of the environmental ramifications of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project and hazards like air pollution and extreme heat should be an indispensable component of the leadership’s focus.

Pakistan has struggled to preserve old economic partners and runs into a brick wall when considering new ones. Last August saw tensions sprout when Qureshi, in an audacious move, challenged Islamabad’s support for Riyadh if Saudi Arabia did not take a firm stand on Kashmir. This resulted in Saudi Arabia—which has moved away from an Islamic foreign policy to one guided by economic interests—canceling a $3 billion loan to Pakistan. Khan’s May 2021 visit to Riyadh—undertaken in hopes of resuscitating Pakistan’s strained relations with its erstwhile economic patron—along with the repayment of a $1 billion loan made possible through Chinese assistance–seems to have done some much-needed damage control, for now.

Closer to home, Pakistan, in a moment of clarity, reconsidered lifting the ban on importing two commodities—sugar and cotton—from India in April of this year. Such a move would have broadened Pakistan’s trading options, reduced prices, and further integrated Pakistan economically in the region, and yet the opportunity was sacrificed to its preoccupation with Kashmir. Prime Minister Khan punctured speculations of a “thaw” in India-Pakistan relations by remarking that trade relations would not come at the expense of Kashmir. To truly realize its geoeconomic potential, Pakistan must de-link its economic outlook from its geopolitical and security whims, and protest issues of geopolitical significance in a way that does not hurt its economic prospects and further feed its aid dependency. To Pakistan’s credit, the ceasefire announced in February by India and Pakistan after decades of border skirmishes is a step in the right direction, especially as the ceasefire remains unviolated since then.

Domestic turmoil bubbles to the surface and threatens all else: Before Pakistan has a chance to flex its potential diplomatic muscles or set its geoeconomic aspirations in motion, Islamabad must contend with ongoing political and social issues—women’s rights, elitism, crackdowns on media freedom, political instability, religious extremism—that undermine its progress. Most recently, the torture of a vlogger—who had criticized the government and military—added another black mark to Pakistan’s poor reputation regarding threats to journalism and media freedom. Meanwhile, 2021 has also been privy to the ban of the extremist outfit Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan following violent protests; a brawl that broke out in the National Assembly; and the opprobrium inflicted upon the 2021 women’s march, not to mention the prime minister’s problematic comments on women’s clothing choices that left many appalled.

Before Pakistan has a chance to flex its potential diplomatic muscles or set its geoeconomic aspirations in motion, Islamabad must contend with ongoing political and social issues… that undermine its progress.

All of the above, coupled with the persistent political opposition faced by the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf government, cast doubt on Pakistan’s capacity to tackle the economic depredations of the pandemic and societal tumults in a competent way. If the recent privatization of vaccines—which would deepen existing socioeconomic fissures—is any indication, domestic strife is likely to subsist throughout the year.

Sri Lanka

By Emily Carll

Halfway through 2021, Sri Lanka’s democratic backsliding shows no signs of abating, and restrictions on religious freedom and human rights continue to grow. Not only is the government emboldened by the lack of any meaningful attention to its abuses from international actors—most of whom are distracted by COVID-19—but the pandemic has increased the country’s reliance on foreign borrowing, tipping the fragile balance of Sri Lanka’s dependence on China. Looking ahead, economic and environmental recovery will be both a difficult and slow process.

Democratic backsliding in human rights, political freedom, and accountability: Throughout 2021, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government has continued to use the pandemic and national security to justify its human rights abuses and increase restrictions on religious freedom with no signs of slowing down. In February, forced cremations of Muslims who had died due to COVID-19 were deemed a matter of “public safety” as the government argued that burials of COVID-19 victims would contaminate the groundwater. This ceased after Sri Lanka was met with international criticism, particularly from Pakistan. The government’s alternative solution, however, was to bury the dead on a remote island in the Gulf of Mannar, around three hundred kilometers from Colombo. In a further move to restrict religious freedom, the already problematic Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA)—which disproportionately imprisons Muslims and Tamils—was strengthened in March when the Rajapaksa government introduced a burqa ban, arguing it necessary as a matter of “national security.” In the latest erosion of Sri Lanka’s “democracy,” President Gotabaya Rajapaksa pardoned political ally Duminda Silva, who was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a political rival and three of his supporters. The lack of accountability for human rights abuses in Sri Lanka allows a convicted murderer to walk free while many remain imprisoned on false and baseless charges under the PTA. These developments indicate that such regressive policies are only accelerating to the detriment of Sri Lanka’s struggling democracy and should be closely monitored for the remainder of 2021.

Regressive policies are only accelerating to the detriment of Sri Lanka’s struggling democracy and should be closely monitored for the remainder of 2021.

A glimmer of hope: If the European Parliament is true to its word and demands actual accountability from Sri Lanka by leveraging their bilateral trade relationship, the Rajapaksa government may be forced to tamp down its human rights crackdowns, even if reforming only the most blatant offenses. International pressure began to mount against Sri Lanka in March of this year, when twenty-two countries in the United Nations Human Rights Council voted to pass a resolution against Sri Lanka. According to Human Rights Watch, they established “a powerful new accountability process to collect, analyze, and preserve evidence of international crimes committed in Sri Lanka for use in future prosecutions.” Since the resolution in March, the European Parliament also issued a statement in June warning the Rajapaksa government that its worsening human rights record will jeopardize its bilateral and trade relations with the European Union (EU).

The EU is Sri Lanka’s second-largest trading partner and second-largest export destination. To appease the EU, the Rajapaksa government released sixteen individuals imprisoned under the PTA. The statement from the EU also triggered a response from Sri Lankan Justice Minister Ali Sabry, who said, “The PTA will be either revised or repealed depending on a report by two committees appointed by the Cabinet.” This is the longest the international spotlight has been on Sri Lanka and its human rights abuses. As such, while a vote against Sri Lanka by the United Nations Security Council would never pass due to China’s and Russia’s veto power, this is a step in the right direction.

Debt burden and foreign policy: The balancing act: Unless India and the other Quad members provide assistance to Sri Lanka to counterbalance its dependence on Beijing, China will likely have an uncontested hand in influencing Sri Lanka’s foreign policy as it recovers from the pandemic. With India failing to deliver on its vaccine promises, Sri Lanka accepted help from China in the form of vaccines, financial assistance, oxygen, personal protective equipment, and more. In addition, Sri Lanka inaugurated the China-Sri Lanka Association for Trade and Economic Cooperation, creating a platform for increased Chinese economic influence in the region. Most recently, Sri Lanka showed its loyalties as it issued a golden coin as “an accolade for long-standing friendship and mutual trust” between the two countries.

This and increased Chinese engagement in Sri Lanka have certainly unnerved India and the other Quad powers. Increased Chinese engagement will also lead to the prioritization of Chinese interests at the expense of Sri Lanka’s. With a default risk of 27.9 percent—the highest in the Asia-Pacific—Sri Lanka may be walking into another Hambantota Port situation.

Recovery from the pandemic and an environmental disaster: Sri Lanka will spend the rest of 2021 attempting to recover from both the COVID-19 pandemic and concurrent crises. Specifically, managing its increasing debt will be one of the crucial pillars of Sri Lanka’s economic recovery. Sri Lanka’s high default risk also makes it likely that the country will go further into debt to repay its existing debts, potentially needing to turn to the International Monetary Fund for financial assistance.

To complicate recovery efforts, a recent fire on the MV X-Press Pearl cargo ship off the coast of Sri Lanka devastated beaches and fisheries with toxic chemicals, plastics, and waste. This unprecedented disaster in Sri Lanka will slow economic recovery due to the country’s reliance on the environment for food and tourism while adding environmental recovery to Sri Lanka’s growing list of priorities for 2021. Scientists predict that this incident will likely lead to years of ecological damage to Sri Lanka and its surrounding environment. With fishermen now out of jobs and people hesitant to eat seafood, immediate recovery efforts will be necessary to restimulate the economy. Finally, if not for the environment itself, tourism will be a driver of the environmental relief efforts as Sri Lanka’s third-largest foreign exchange earner. The country will be targeting efforts to curb the impacts of the disaster in hopes of setting tourism back on track and stimulating its economy.

The South Asia Center serves as the Atlantic Council’s focal point for work on greater South Asia as well as its relations between these countries, the neighboring regions, Europe, and the United States.

The authors

Fahim Ahmad is a project assistant at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Areeba Atique is a young global professional with the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center and a fellow with the American Pakistan Foundation.

Emily Carll is a project assistant at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Ayra Khan is a research assistant at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Capucine Querenet is a project assistant at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Harris Samad is assistant director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Kaveri Sarkar was a project assistant at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

All photos courtesy of Reuters.

More from the South Asia Center

Image: People shop at a crowded wholesale vegetable market after authorities eased coronavirus restrictions, following a drop in the coronavirus cases, in the old quarters of Delhi, India, on June 23, 2021. Photo via REUTERS/Adnan Abidi