A reinvigorated Quad is becoming a key element of the new US administration’s Asia policy. Its members—Australia, India, Japan, and the US—convened virtually in March at the leader level. Amid multiple global crises, they wisely opted to focus on concrete ways to deliver for their people and the region. The grouping sought to prove that democracy still works, as President Biden likes to say. The Quad Leaders’ communique set the bar high: cooperation on “the defining challenges of our time.”

Largely across US party lines, the consensus is building that China’s economic and military aggression ranks high among defining global challenges. But rather than construct an anti-China military alliance, the Quad has so far opted for a pragmatic and unifying focus on urgent global problems. That decision in part acknowledges India’s reluctance to antagonize China, especially while their border dispute remains unresolved. The smaller ASEAN countries and, to a lesser extent, even linchpin US ally South Korea, are wary of being jostled about by major power competition. More fundamentally, the region wants to tackle pressing issues like the pandemic and climate change.

Hopes were high in the early spring that the Quad’s ambitious plan for India to manufacture one billion vaccines, with financial and logistical assistance from the others, could help bring the COVID-19 pandemic to a swift conclusion. Southeast Asia was to be a primary beneficiary. But that was before a catastrophic second wave struck India, and the delta variant laid siege to unvaccinated Americans. The in-person Quad Leaders summit should clarify where the promising vaccine partnership stands.

The coalition also identified climate change as a top priority back in March. Since then, the countries appear to have stepped-up their cooperation in the last few months. For instance, Special Envoy John Kerry launched a new climate financing mechanism while in India last week. With COP26 mere weeks away and faith in global efforts wavering, the Quad countries need to demonstrate their firm commitment to cleaner technologies and support for emissions reduction.

The partners will also discuss progress related to critical and emerging technologies—now a significant dimension of preserving free and open societies. They will exchange views on reducing escalating tensions over the Taiwan Strait and addressing the tragedy unfolding in Myanmar. While defense ties are not the leading edge of the Quad, the leaders may not pass up the opportunity for discrete conversation about Western Pacific and Indian Ocean security.

The US and NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s reemergence elevates longstanding security concerns for India, in particular. New Delhi’s dodgy neighborhood has undoubtedly grown more dangerous. India-focused terrorist groups are likely emboldened by the return of an especially strict variant of political Islam to Afghanistan. In the past, the Taliban provided a playground for violent extremists targeting India and the West. The growing imperative for India to secure continental borders could distract from Asian maritime activities, unless likeminded friends can help it manage the increasing risk of terrorism.

The Quad Leaders will be meeting right after the big reveal of AUKUS, a new Indo-Pacific coalition launched by Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. AUKUS should complement the Quad’s early focus on non-military issues. Unlike it, the newcomer will be focused squarely on defense, related science, and technology cooperation. This emphasis reflects Washington’s serious determination to work with allies to create a favorable balance of power to deter China. Europe also remains critical to this project. It is worth exploring whether India or Japan can use growing Indo-Pacific cooperation with France to help smooth over Paris’s recent public disagreement with Canberra, Washington, and London.

The essential point remains this: In the past 18 months, China has resorted to economic coercion against Australia and Europe, military coercion against India, and elevated regional anxiety levels through heightened sovereignty claims, often far from established borders. To the extent AUKUS can induce greater caution and restraint from China around its periphery, that should be a welcomed development for India, the Quad, and the region.

The Quad and likeminded democracies are all eagerly exploring overlapping security arrangements in response to a shifting power balance. While they do so, it is vital that these liberal societies take the necessary steps to secure democratic institutions against the polarizing forces of nationalism, populism, and xenophobia. Distracted or divided democracies often have a way of letting domestic politics seep into foreign policymaking, which can lead to national interests being defined more narrowly to the detriment of international partners.

Coalitions like the Quad are important, but they are no substitute for united, open, and resilient societies. Both will be necessary to uphold regional peace and prosperity.

Atman Trivedi is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center and has over twenty years of foreign policy and trade experience with expertise in India and the broader Asia region.

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related content

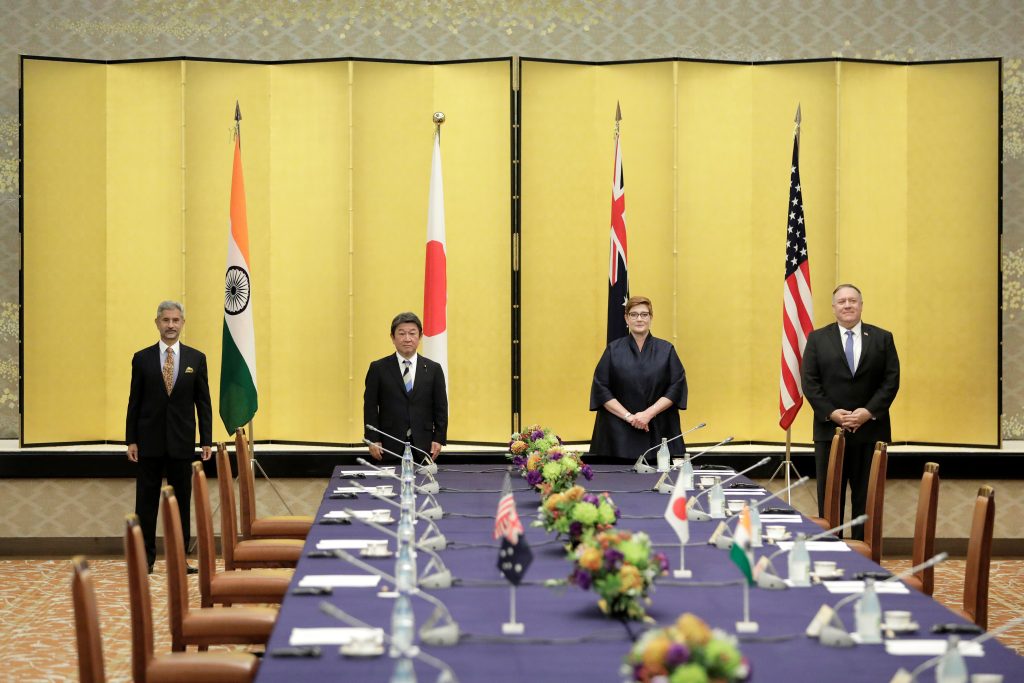

Image: Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, Japan's Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi, Australia's Foreign Minister Marise Payne and U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo pose for a picture prior the Quad ministerial meeting in Tokyo, Japan October 6, 2020. Kiyoshi Ota/Pool via REUTERS