The feeling of dread and fear all Pakistanis are familiar with returned when a bomb blast ripped through a Shia mosque in Peshawar on March 4, 2022. Three days later, another suicide attack targeting a cultural festival killed five Frontier Constabulary paramilitary personnel in Sibi, Balochistan. Scores of people dying in suicide bombings reminded Pakistanis of the dark days of 2009 and 2010, when terror had a tight grip over the country. Is the recent uptick in suicide attacks a harbinger for the eventual return of the days of terror? If so, how will Pakistan counter another wave of terrorism, this time without an American presence in the region and with limited fiscal and military support?

There were over forty militant groups active in Pakistan for nearly two decades. Many of them conducted attacks in Afghanistan and India, but some, particularly the militant consortium of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), targeted civilians and state institutions within the country. They killed thousands of innocent civilians and brave soldiers. Suicide bombings became commonplace, upending many lives and livelihoods.

In time, US drone strikes along with Pakistani military operations severely degraded the TTP’s operational capabilities, killing its commanders and forcing its leadership to flee. Meanwhile, other Waziristan-based militant groups such as the Nazir group and other militias forming the Punjabi Taliban either dissipated or signed peace pacts with the government. There was, for a time at least, relative calm across the country—with an emphasis on relative.

However, the recent uptick in terrorist attacks provides evidence of a resurgence of militancy in the country. As early as 2018, many residents of Pakistan’s tribal belt, formerly known as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), informed me that militants were trickling back into the country from Afghanistan. “We see Taliban commanders again, sitting at tea shops, roaming the streets, as if nothing ever happened,” one resident of North Waziristan told me, referring to the Pakistani military’s Operation Zarb-e-Azb that was launched in 2014.

It is widely believed that the TTP resurfaced only after the Afghan Taliban took over Kabul last summer. Indeed, the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan was interpreted as a strategic win for all Islamist militant groups. However, as Waziristan residents told me, the TTP had been slowly regrouping ever since Noor Wali Mehsud took over its reins in 2018.

Known to be savvy and an intellectual, Noor Wali sought to unite the disparate and disgruntled militant groups across the country, reestablishing the TTP as an umbrella group or consortium, just like Baitullah Mehsud, its first chief, did.

Under Noor Wali, it appears that the TTP is back with a bang. It has a slick media and communications campaign and active social media presence. The TTP chief even gave his first media interview to CNN last year. Recently, he began making overtures to militant commanders, particularly those who had parted ways because of their contempt for Maulana Fazlullah and his brash TTP leadership (from 2014-2018, until he was killed in a US drone strike).

Not only did Noor Wali rekindle old ties across Pakistan’s tribal belt, but he also forged new alliances with Baloch separatists operating in the southwest of the country. Both the TTP and Baloch insurgent groups claim to be at war with Pakistani security forces—and the savvy Noor Wali Mehsud brokered collaboration to garner more muscle and might.

Unholy alliances

Many South Asia security watchers were confused when the TTP claimed responsibility for targeting Chinese workers and potentially the Chinese Ambassador to Pakistan while he was visiting Balochistan. Such attacks are usually planned by the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA), a separatist group claiming to fight for indigenous rights over the province’s natural resources. However, with a sharp rise in TTP-style terrorist incidents—particularly suicide bombings—targeting China-Pakistan Economic Corridor projects and security forces in Balochistan, the presence of a TTP-BLA nexus is undoubtedly clear. Baloch separatists did not previously have a history of using suicide bombers.

As residents of the tribal areas forewarned me about the TTP’s resurgence in 2018, they also apprised me of more ominous developments. They chillingly mentioned ISIS, whose affiliate in South Asia known as Islamic State-Khorasan Province (IS-K) invoked a kind of fear among residents that I had not witnessed before. “They’re a different breed altogether,” one journalist from the former FATA told me. Another researcher from the area described them as “ruthless” and “bloodthirsty.”

These groups comprise a host of disgruntled fighters from the TTP’s most violent splinter groups, like Jamaat ur Ahrar (JuA) and Lashkar-e-Islam. Most of them escaped to Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province after the Pakistani military offensive of 2014. After IS-K grew in eastern Afghanistan in 2015, the Afghan Taliban declared war against the group, pushing them into Pakistan and in particular the Khyber and Orakzai agencies. This is where IS-K slowly began to gain ground in Pakistan.

The TTP has denounced IS-K—it essentially had to in order to keep ties with the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS). But this denouncement seems fluid, just like their fighters. The TTP’s Umar Media announced that JuA had rejoined the TTP, while some JuA fighters merged with IS-K. They tap into the same financial and militant networks, and they are competitors, not adversaries. There have been no instances of violence between the two groups yet.

Terror redux?

This mosaic of terrorist groups is an ominous development for Pakistan, which is trying to reset its image in the region and the world. Pakistan, in its recently promulgated National Security Policy, focused on the country’s geoeconomic strengths and weaknesses while prioritizing its economic and human security. Pakistan’s national security establishment is actively trying to make the case that the country has an image problem, which it can now improve as the West will not look at Pakistan transactionally vis-à-vis the US war on terror. Hence, it is undergoing a rebranding of sorts by focusing on its geoeconomic potential.

But the resurgence of militant groups, especially IS-K, will render Islamabad’s goals unattainable. These organizations have regrouped slowly and steadily right under the government’s nose, all while Pakistan was distracted, either in its efforts to broker negotiations with the Afghan Taliban or dealing with rising extremism in India.

With political wrangling currently underway—Prime Minister Imran Khan facing a no-confidence motion, political opposition members organizing long marches across the country, and civil-military disagreements—there is no united policy or strategy to crush this rising tide of militancy. Consequently, Pakistan will continue to be viewed with a security lens by the West and other external stakeholders.

And, in this environment, Pakistan will be on its own. The United States has not only departed from the region, but it is mired in caustic domestic politics while trying to contain a war in Europe. Indeed, though military-to-military cooperation between Pakistan and the United States is continuing–evident from joint naval and maritime exercises as well as the recent Falcon Talon exercises between the Pakistan Air Force and US Air Force–there seems to be little appetite in the White House for otherwise increased cooperation.

The Biden administration is also still seething from its embarrassing withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul—the latter it attributes to the safe haven and support provided by Pakistan. As vice president in the previous Obama administration, US President Joseph R. Biden engaged with Pakistan many times, working with the US Congress to pass the Kerry-Lugar bill while urging for action in North Waziristan and against the Quetta Shura. But neither Pakistan’s government nor its military budged at the time, and actively vilified the Kerry-Lugar bill in the media. Biden has learned his lesson, and likely does not believe that Pakistan will change its policies.

There should therefore be no expectation of the same US counterterrorism assistance Pakistan had in the past. “Pakistan Fatigue” is real and here to stay in Washington. Prime Minister Imran Khan and his National Security Adviser Moeed Yusuf even complained that they have not received a phone call from President Biden since Khan took office in 2018. Given these circumstances, Biden will most likely not make that phone call, and Pakistan will be on its own dealing with a turbulent Afghanistan to the west, an increasingly antagonistic India to the east, and formerly battered terrorists seeking revenge at home.

Neha Ansari is a PhD candidate at Tufts University and a lecturer at George Washington University.

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Related content

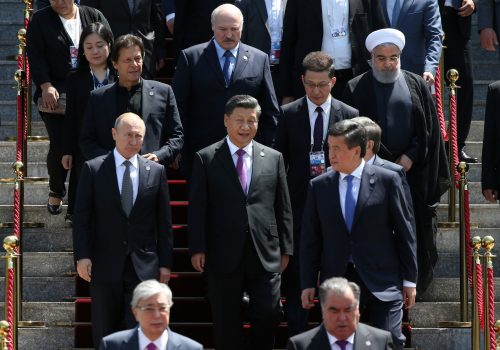

Image: An army soldier stands amid the damages at the prayer hall after a bomb blast inside a mosque during Friday prayers in Peshawar, Pakistan, March 4, 2022. REUTERS/Fayaz Aziz