Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has emerged as one of the world’s harshest critics of Israel’s response to Hamas’s October 7 terrorist attack. Yet Erdoğan did aspire to secure a role for Turkey in de-escalating the conflict and to serve as a “guarantor” of a future ceasefire and peace agreement. Despite Erdoğan’s change in tone and adoption of anti-Israel vitriol, Turkey could still possibly play a mediating role—and it could well be a useful one for Palestinians, Israelis, and all who seek peace in the Middle East, considering Turkey’s experience with conflict mediation and peacekeeping.

The Israel-Hamas war broke out just as efforts by Israel and Turkey to normalize their diplomatic relations were gaining steam. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Erdoğan held their first-ever meeting in person in New York on September 19, just a few weeks before October 7. The discussion reportedly went well, clearing the way for a new phase of bilateral cooperation. One former ministerial-level Israeli official affirmed to me at that time that Netanyahu acceded to Erdoğan’s request to focus on joint energy projects, while a current ministerial-level Turkish official told me that Ankara believes Israel was then ready to resurrect a natural gas pipeline project connecting its giant Leviathan field in the Mediterranean Sea with Turkey.

Following such efforts to normalize relations, Erdoğan’s initial statements after Israel’s military response in Gaza were restrained. On October 7, Erdoğan called upon “the parties to act with restraint in light of the events in Israel this morning and to stay away from impulsive steps that will escalate tension.” Four days later, the Turkish president told members of his party, “We openly oppose the killing of civilians on Israeli territories. Likewise, we can never accept the massacre of defenseless innocents in Gaza by indiscriminate, constant bombardments.”

As Israel’s bombardment of Gaza intensified and civilian casualties mounted, however, Erdoğan’s tone shifted back toward his more typical support for the Palestinian people. His anti-Israel rhetoric crescendoed for a fortnight, peaking in late October when the Turkish president said to his party that Hamas fighters are liberators, and when—at a pro-Palestinian rally in Istanbul—he told hundreds of thousands of supporters, “Hamas is not a terrorist organization,” and “Israel is an occupier.” At the rally, Erdoğan further said that Turkey would “declare Israel a war criminal” and that Netanyahu “is no longer someone we can talk to, we have crossed him out.”

Despite this rhetoric, it could still be valuable for Turkey to play a leading role in diplomatic efforts to secure a ceasefire and then pursue a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict. Ankara has succeeded in mediating in the past, particularly in facilitating talks (in collaboration with the United Nations) between Russia and Ukraine, resulting in the Black Sea grain deal in July 2022—although the deal fell apart a year later. In addition, Turkey is home to NATO’s second-largest military and has extensive peacekeeping experience in Afghanistan, Lebanon, Somalia, and Kosovo. The Turkish president may have been angered when US Secretary of State Antony Blinken—during his first post-October 7 trip to the Middle East—skipped visiting Turkey, which could have suggested that the United States didn’t see Turkey as a possible mediator. Later that month, Erdoğan seemed to have snubbed Blinken by not meeting him when he visited Ankara.

Turkey, among other countries, has offered to mediate and serve as a “guarantor” to end the conflict and to ensure the implementation of a political solution. However, the guarantor proposal—first outlined by Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan on October 17—has not gained traction despite Fidan’s flurry of international diplomacy, including at the Cairo Peace Conference on October 21 as well as talks in London and Paris. Instead, Qatar (in coordination with Egypt and the United States) led negotiations to obtain the week-long “humanitarian pause” that began on November 24 and included hostage and prisoner releases plus aid deliveries into Gaza from Egypt.

In the future, Qatar and Turkey could form a valuable diplomatic partnership to pursue additional humanitarian pauses or even an eventual ceasefire, building on their existing (and strong) security and economic relations. Turkey maintains a military base in Qatar under the Qatar-Turkey Joint Forces Command and was Doha’s staunchest supporter when Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates blockaded Qatar from 2017 to 2021. Doha, meanwhile, has provided Ankara significant financial support, including a $500-million presidential jet that Emir of Qatar Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani donated to Erdoğan in September 2018.

The trust Qatar has garnered from both Israel and Hamas coupled with Turkey’s military and diplomatic capabilities could eventually enable multilateral discussions about a two-state solution. And despite his bitter rhetorical attacks on Netanyahu and Israel, Erdoğan has arguably kept the diplomatic door ajar by allowing Turkey’s diplomatic mission in Israel to remain open.

Moreover, Israel and Turkey have muddled through previous bouts of intense diplomatic tensions. Following the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident—when Israeli commandos killed eight Turkish citizens and one Turkish American during a raid on the flagship of a flotilla trying to break Israel’s blockade of Gaza—Israel-Turkey relations entered a deep chill. Yet (despite episodic and reciprocal withdrawals of each country’s ambassadors) the countries largely kept their respective embassies open and bilateral trade and investment continued to flourish, leading to a doubling of the two countries’ trade volume from $3.4 billion to $8.4 billion by 2021.

But that was before October 7, the day the largest loss of Jewish lives since the Holocaust took place. For the foreseeable future, Israel’s entire political spectrum will remain shaken and embittered by Erdoğan’s embrace of Hamas and condemnation of Israel and will thus recoil at any suggestion of a “guarantor” role for Turkey.

Still, Turkey’s past engagement with Hamas could pay dividends for peace in the Middle East. Erdoğan disclosed on November 21 that Fidan and Turkey’s intelligence director, Ibrahim Kalın, were working with Qatar on the release of hostages held by Hamas. These efforts appear to have produced results. Even Hamas credited Turkey for having facilitated the release of citizens held by Hamas, saying in a November 27 statement, “In response to the efforts of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Islamic Resistance Movement Hamas has completed the release of Thai detainees inside the Gaza Strip.” Moreover, Turkey’s ambition to be a “guarantor” of a future ceasefire and eventual political solution could help persuade Egypt and other countries to play an eventual role on the ground and avoid a political vacuum in Gaza.

What is less evident, however, is whether Erdoğan will moderate his rhetorical attacks on Israel, and even if so, whether Israelis, stung by Ankara’s embrace of Hamas, would even accept Turkey (in tandem with Qatar) as a mediator or guarantor in achieving tangible benefits in Gaza.

Matthew Bryza was a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center and the Atlantic Council IN TURKEY.

Further reading

Wed, Dec 6, 2023

Erdoğan’s rhetoric on the conflict in Gaza puts much more than the Israel-Turkey relationship at risk

TURKEYSource By

The president's shifted rhetoric towards Israel may impact Turkey's credibility in the region as a power broker.

Fri, Jul 21, 2023

What’s behind growing ties between Turkey and the Gulf states

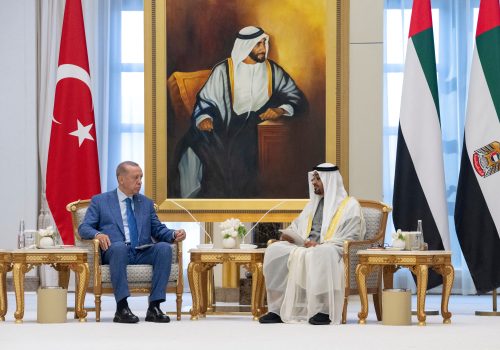

TURKEYSource By

Erdoğan's tour of the Gulf opens a new chapter in Turkey's political and economic relations with the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar.

Thu, Nov 10, 2022

With an eye on Iran, Turkish-Israeli relations will deepen

TURKEYSource By Pınar Dost

Driven by strong regional imperatives, Turkey-Israel relations are warming quickly. After a decade long rift, the two countries have many areas to benefit from cooperation.

Image: Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan and Qatar's Emir Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al Thani walk to pose for a family photo during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, December 1, 2023. REUTERS/Thaier Al-Sudani