With anti-interventionist sentiment becoming clearer in Mali and recent political turmoil in Niger, Francophone African countries in the Sahel seem to be stripping themselves of their French colonial legacies.

Once a vital player, France now has a footprint on the continent that is rapidly fading away, with few prospects for its return. This void creates an opportunity for the West’s adversaries—particularly China, Russia, and Iran—who are asserting an increasingly active stance in Africa.

France is leaving behind a power vacuum; Turkey’s strategy in Africa offers lessons for NATO on how to fill it.

Ankara’s ‘soft’ approach

Ankara’s foreign policy in Africa rests on a careful balance of soft and hard power. On one hand, Turkey’s cultural and political engagement with Africa has been a prominent element in Ankara’s foreign policy since the late 1990s. As Elif Çomoğlu Ülgen, general director of Eastern and Southern Africa at the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, explained in a recent panel discussion, the political-cultural opening to the continent gained momentum with the proliferation of Turkish embassies across Africa and the expansion of Turkish Airlines’ flight network, connecting Ankara to many African capital cities.

Turkey’s strategic opening to Africa, and Turkey-Africa relations overall, gained attention in 2005 with Ankara’s “Year of Africa” agenda. According to the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the initiative helped pave the way for enhanced political and economic ties, including trade cooperation agreements, with African countries. That year, the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency opened its first office in Africa; now it has more than twenty offices across the continent, implementing culture and development projects. Over the last few decades, Turkey has signed free trade agreements with five African nations: Morocco, Tunisia, Mauritius, Sudan, and Egypt. From 1980 to 2017, the trade volume between Turkey and several African countries grew dramatically: For example, Turkey-Algeria trade tripled, while Turkey-Egypt trade increased by five times. The improvement in relations was also accompanied by the expansion of efforts to promote the Turkish language and culture on the continent.

Today, thousands of African students study in Turkish universities or among the Turkish Cypriot community with the help of Turkish scholarships. Additionally, Turkey’s Maarif schools provide Turkish-language education to around twenty thousand students across twenty-four African countries. Under the ruling Justice and Development Party, Turkish-African relations improved further, with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan saying that the Turkish people and African populations had built “heart-to-heart” connections. Such heart-to-heart connections were evident in state visits, with Erdoğan’s 2011 visit to Mogadishu amid a large-scale famine and drought that affected more than twelve million people across the Horn of Africa.

Turkey’s ‘hard power’ contributions

In addition to using soft power, Turkey has deployed hard power—in the form of its burgeoning defense diplomacy and military-capacity building—to connect with African countries. The positive momentum in Turkey-Africa relations has also led to closer security-military cooperation, specifically in counterterrorism operations.

As Turkey struggles with its own decades-long terrorism problem with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party—a Kurdish militant group which Turkey, the United States, and the European Union recognize as a terrorist organization—Ankara can empathize with its African partners who are facing their own challenges from terrorist groups. As these countries look to combat terrorism, Turkey exports lessons learned from its counterterrorism operations to its African partners.

Turkish companies have sold armored vehicles to African countries; the Turkish government has donated such vehicles to some countries as well. Troops in Kenya, Chad, and Somalia are pursuing terrorist groups with the help of these Turkish armored vehicles.

Additionally, Turkish drones hover over the African continent. An increasing number of African nations—including Niger and Ethiopia—are deploying Turkish unmanned aerial systems to conduct pinpoint strikes and collect intelligence on terrorist targets.

Several announcements from Turkish officials and improving Turkey-Africa relations suggest that the Turkish defense industry’s footprint in the continent might deepen in the future. Importantly, in contrast with some other countries arming African nations, Turkey’s military policy involves a high degree of cooperation, after-sale support, and other forms of assistance. In this sense, Ankara is transferring its concept of operations to African countries such as Somalia.

In addition to equipping the Somali Armed Forces with high-end Turkish weapons systems, Turkey also established a defense university, Camp TURKSOM, in Mogadishu in 2017 to train Somalia’s military. Such a university demonstrates that for Turkey and Somalia, their military relations rest on bolstering their joint capabilities (rather than simply a set of transactions), strengthening Somalia’s security, and fostering a common identity for the two nations’ armed forces. Additionally, Turkish military policy in Africa has remained mostly unchanged despite recent security challenges in the region and the open threats Ankara has received from terrorist organizations such as al-Shabaab. This unchanged posture shows the importance and depth of its military-security cooperation with Somalia.

Beyond its involvement in counterterrorism and capacity-building efforts in Africa, Ankara’s positioning in recent affairs in the region also differs from the positions taken by many other NATO countries. During the recent political turmoil in Niger, while some countries cut off or threatened to halt humanitarian aid, Turkey refrained from making bold claims on the matter. Later, Erdoğan opposed proposals for a military intervention in Niger and expressed hopes that the country could reach constitutional order and democratic governance soon. This noninterventionist stance seems closely tied to Ankara’s strategic objective to establish a long-lasting relationship with Niger—and to possibly secure the continuation of military-security cooperation deals signed between Ankara and Niamey (which involve the prospect of opening a military base in Niger) and protect Ankara’s investments in the country, which depend on Niger’s stability.

Moving forward, the steps NATO allies take in Africa will greatly shape the continent’s geopolitical orientation. As Western capitals are increasingly pushed to recalibrate their Africa strategies, Ankara’s approach—one that rests on the pillars of a careful mix of hard and soft power, capacity building, noninterventionism, and mutual cooperation—can provide lessons. And while that process is underway, Turkey—whose political-military ties to the continent sit on strong foundations—can help counterbalance the growing footprint of NATO’s strategic rivals.

Sine Özkaraşahin is an analyst in the security and defense program at the Istanbul-based think tank the Centre for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies. Follow her on X (formerly known as Twitter) @sineozkarasahin.

Further reading

Thu, Sep 28, 2023

What’s behind the strengthening UK-Turkey partnership?

TURKEYSource By

As the United Kingdom adjusts to its post-Brexit reality, Turkey is emerging as a key partner with converging interests.

Mon, Aug 14, 2023

The United States can’t offset its rivals in Central Asia alone. Turkey can help.

TURKEYSource By

Turkey is well-positioned to counter US rivals in Central Asia by expanding its influence and diversifying the region's partners.

Fri, Jul 21, 2023

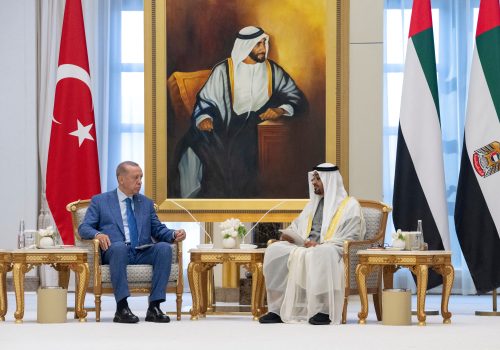

What’s behind growing ties between Turkey and the Gulf states

TURKEYSource By

Erdoğan's tour of the Gulf opens a new chapter in Turkey's political and economic relations with the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar.

Image: Somali supporters of Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan hold Turkey's flag during celebrations after the second round of the presidential election, in Mogadishu, Somalia May 29, 2023. REUTERS/Feisal Omar