Vladimir Putin’s regime is much easier to understand than it might first appear. In October 1939, Winston Churchill famously stated that Russia “is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.” That was a long time ago. Today, the key is crony capitalism. Putin is about two things—power and wealth.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2000, the American journalist Trudy Rubin famously asked a panel of Russians: “Who is Mr. Putin?” Wisely, none of them answered. During his first term as president, 2000-2004, Putin consolidated power by being everything to everybody, and the Russian market economy worked better than ever. An obvious parallel is to the first term of Turkish strongman Recep Tayyip Erdogan from 2003-2007. Both have degenerated as they have consolidated power.

Putin’s second presidential term was premeditated by the arrest of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the main owner and CEO of the Yukos Oil Company, and Russia’s richest man when he was arrested on October 25, 2003. The ensuing confiscation of Yukos amounted to a war on the oligarchs, but the other big businessmen kept quiet. The essence of Putin’s second term was state capitalism. Putin did not care about the efficiency, social values, or profitability of state companies. He wanted control through loyalists in charge who transferred the surplus of the companies toward him and his friends. Accordingly, the market value of Gazprom has sunk from a peak of $369 billion in May 2008 to currently barely $60 billion. CEO Alexei Miller who has cost the company $310 billion remains in place, showing that Putin does not mind.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

During Putin’s third informal term, Dmitri Medvedev was formally president. Then Putin went all out, opting for real crony capitalism. His friends indulged in massive asset stripping from state companies, chiefly from Gazprom. The four primary cronies are long-time friends of Putin from St. Petersburg. The brothers Arkady and Boris Rotenberg make money on building pipelines for Gazprom and roads for the Russian state in no-bid contracts. Gennady Timchenko also builds gas pipelines but he also produces gas benefiting from favorable licenses. Yuri Kovalchuk, CEO of Bank Rossiya, is in charge of financial and media asset stripping from Gazprom and controls twenty television channels. In March 2014, the US sanctioned all four and their companies, while the European Union did not sanction Boris Rotenberg and Timchenko, because they had acquired Finnish citizenship in the 1990s.

After Putin resumed the presidency in 2012, his rule is best described as “manual management” as the Russians like to put it. Putin does whatever he wants, with little consideration to the consequences with one important caveat. During the Russian financial crash of August 1998, Putin learned that financial crises are politically destabilizing and must be avoided at all costs. Therefore, he cares about financial stability. Russia maintains huge currency and gold reserves, balanced budgets, minimal public debt, low inflation, and tiny unemployment.

In contrast, Putin could care less about the standard of living or economic growth. Officially, Russia’s disposable incomes declined by 13 percent from 2014-2018, but before the statistics were revised it was even 17 percent, and the decline continues. After a decade of 7 percent growth a year, Russia has had an average economic growth of 1 percent a year since 2009.

A key question is how much wealth Putin has accumulated. The irony is that having undermined all property rights in Russia, Putin and his cronies are compelled to launder their loot in offshore havens. If they were to lose power in Russia, they would also lose all their assets there.

Total Russian private wealth held abroad is assessed at $800 billion. My assessment is that since Putin’s circle got its looting fully organized around 2006, they have extracted $15-25 billion a year, reaching a total of $195-325 billion, a large share of the Russian private offshore wealth. Presuming that half of this wealth belongs to Putin, his net wealth would amount to $100-160 billion. Naturally, Putin and his cronies cannot enjoy their wealth. It is all about power. If they are not the wealthiest, they fear they will lose power.

Putin’s crony capitalism condemns Russia to near stagnation for as long as he stays in power. No political or economic reform is on his agenda, since reform would undermine his political power. Instead, Putin needs foreign adventures, such as the wars in Georgia, Ukraine, and Syria to rally his people around the flag.

The best defense of the West against Putin’s authoritarian and kleptocratic regime is transparency, shining light on this anonymous wealth, which is probably held predominantly in the United States and the United Kingdom, the two countries with good rule of law that allow anonymous companies on a large scale and have deep financial markets.

Anders Åslund is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and author of the new book “Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy” (Yale UP).

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values, and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia, and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

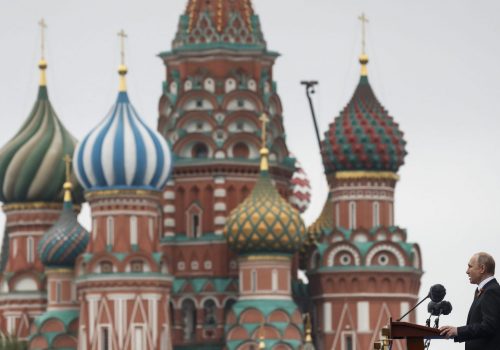

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin meets with public in Crimea on March 18, 2019. Credit: Kremlin.ru