The Black Lives Matter movement has led to a wave of monument removals across Europe and North America in recent weeks as people reflect on the appropriateness of the historic figures enjoying pride of place in their towns and cities. This reckoning with the past has encompassed everything from memorials honoring Confederate generals to statues of English slave traders and European monarchs. Some have been toppled by mobs, while others have been quietly removed. For supporters, this trend represents belated recognition of grave historical injustices. Critics, meanwhile, see it as an attack on heritage and identity. The ensuing debate has energized audiences on both sides of the Atlantic and threatens to become a feature of this year’s US presidential election campaign.

The intensity of these memory wars has taken many by surprise, but the competing arguments they involve are all too familiar when viewed from Ukraine. Ever since their country first gained independence in 1991, Ukrainians have struggled with a national identity crisis rooted in rival interpretations of the country’s turbulent past. Advocates of a clean break from the Soviet era have embraced a liberation narrative that depicts Ukraine as a post-colonial country looking to shed the vestiges of Russian domination. Opponents of this approach have rejected attempts to portray Ukraine as a victim and instead sought to maintain traditionally close ties with Russia. This has resulted in increasing political polarization that has often expressed itself in the removal or erection of contentious monuments.

Ukraine’s memory wars have rumbled on throughout the past three decades and been marked by periodic escalations. Since the early 1990s, streets have been gradually renamed, Soviet symbols have been removed from public places, and countless monuments have been dismantled. This was initially most evident in western Ukraine, before gathering momentum in central Ukraine and the east of the country during the 2000s. The 2004 Orange Revolution was a particularly important landmark in the evolution of Ukraine’s post-Soviet identity, leading to reevaluations of the country’s past and greater awareness of Soviet crimes against humanity. Pro-Kremlin forces fought back by rallying around the memory of the USSR’s WWII experience and the Red Army’s lead role in the defeat of Nazi Germany.

The biggest turning point for independent Ukraine’s evolving national identity came in early 2014, when the country’s Euromaidan Revolution reached a bloody climax and was rapidly followed by the Russian invasion of Crimea and eastern Ukraine. Much like the Orange Revolution a decade earlier, Ukraine’s Euromaidan protest movement was driven by a desire to embrace democratic European values while rejecting the authoritarianism associated with both the Soviet past and the contemporary Russia of Vladimir Putin.

When the protests first erupted in Kyiv, thousands of Soviet monuments remained in place across Ukraine. The most prominent Lenin statue in the Ukrainian capital was the first to be toppled. It came down in December 2013, setting the tone for the months ahead. As events escalated in early 2014 and it became increasingly obvious that Moscow sought to undermine Ukrainian independence, the removal of Soviet statues took on a defiant character and merged with the wave of resistance sweeping the nation.

The Ukrainian government then attempted to formalize this process, introducing a series of Decommunization Laws in spring 2015 that outlawed most Soviet monuments and mandated name changes for streets, villages, towns and cities honoring Soviet figures. When the dust finally settled in 2017, thousands of Lenin monuments had been dismantled, while changes to place names had transformed the map of Ukraine.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Ukraine’s decommunization drive did not bring the country’s memory wars to an end. Some felt the process did not go far enough and continue to push for further changes. Others objected to the removal of familiar local landmarks or accused the authorities of attempting to rewrite history. Meanwhile, the appearance of replacement statues and place names caused an entirely new round of confrontations.

While public disagreements continue, there are also strong indications that many Ukrainians are tired of endless disputes over the country’s past. TV comedian Volodymyr Zelenskyy was careful to avoid Ukraine’s divisive memory politics during his 2019 presidential election campaign. Instead, he played down the importance of historical controversies and appealed for national unity. This proved hugely popular and helped him secure a landslide victory over incumbent Petro Poroshenko.

Since taking office in May 2019, President Zelenskyy has continued to distance himself from contentious historical themes. During his annual New Year address to the nation, Zelenskyy directly questioned the importance of the country’s recent enthusiasm for toppling monuments and renaming streets. “What difference does it make?” he asked. This convenient stance allows Zelenskyy to avoid unpopular or polarizing positions, but it also risks abandoning the national identity debate to populist politicians and extreme elements.

With its epic memory wars showing no signs of waning, Ukraine serves as both a fascinating case study and an important cautionary tale for other countries that are currently wrestling with their own histories and looking to reevaluate the past. The Atlantic Council invited a number of Ukraine observers to reflect on Ukraine’s recent decommunization efforts and asked them to consider what lessons could be learned from the country’s extensive monument-toppling experience.

Olesya Khromeychuk, Teaching Fellow, Department of History, King’s College London: Injustice is invisible. Whether because of the color of one’s skin, one’s gender, or social background, it is experienced daily by all who lack the good fortune to be born into privilege, but it mostly goes unseen. What is visible is the celebration of those who were instrumental in the perpetuation of this injustice. When the match is lit in a powder keg, as was the case with the beating of protesters by riot police in Kyiv in 2013, or the killing of George Floyd by the police in Minneapolis in 2020, people look for an object that can embody that invisible but omnipresent injustice. That’s when monuments take center stage.

When, in 2013, Kyiv’s most famous Lenin fell, starting an avalanche of Soviet monument removals all over Ukraine, it was very much in the spirit of rebellion against abuse of power and curtailing of freedoms. Lenin was not only the symbol of decades of Soviet rule, but also of the ongoing interference of the Kremlin, corruption, and injustice. For some time, the plinth where Lenin had stood was occupied by a golden toilet, an apt metaphor for Ukraine’s obscene inequality. In reaction to the spontaneous toppling of Lenin monuments, the Ukrainian state ordered a top-down “decommunization” of the country. This was an attempt by the authorities to take charge not only of national memory but also of the history that was unfolding before its eyes.

Decommunization was criticized for conducting only superficial consultations with local communities on the removal of monuments and the changing of place names, and for using Soviet-style, centralized methods to remove traces of the Soviet past. Nevertheless, the job was done: most of the monuments to Soviet leaders are gone, apart from those that remain in Crimea, the occupied territories of eastern Ukraine, and the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone.

Was formal decommunization in Ukraine the acknowledgment of injustice that the protesters had sought when they toppled the first Lenin? To some degree. But cleansing the country of the symbols of past abuses of power can hardly keep at bay the wrath of the public towards current political mishandling, especially when governments change but injustice remains. If there’s one thing those in power in Ukraine, and elsewhere in the world, can learn from the recent Ukrainian experience, it is not to wait for public anger to reach the level when monuments get toppled.

Vladislav Davidzon, European Correspondent, Tablet magazine: Decommunization in Ukraine was in many ways a long overdue process that could not have been avoided. It was also in many instances mismanaged in a polarizing and haphazard fashion which only served to undermine important relationships with the country’s neighbors and allies. Ukraine’s diplomatic relations with Romania, Hungary, Poland and Israel all suffered to one extent or another because of inflexibility in presenting strongly held memory policies. Indeed, the Hungarian case was bad enough to cause long-term damage to Ukraine’s core national interests such as the cause of NATO integration.

Armed mobs taking down statues by force, without the benefit of any sort of legal process or fair procedure, is not just unfair; it also leads to unpredictable side-effects and fallout that can ripple through society. The polarizing political climate of monument removal in Ukraine after 2014 was at least partially responsible for the the backlash towards Westernizing and modernizing impulses that emerged among a portion of Ukrainian citizens, particularly in the south and east of the country where nostalgia for the Soviet past has traditionally been stronger. It also played into the hands of propagandists who did not have Kyiv’s best interests at heart, while at the same time strengthening the Kremlin’s revisionist agenda, which revolves around the glorification of WWII and the rehabilitation of at least certain aspects of the Soviet era.

Ukraine’s experience is a reminder of how moving too quickly and attacking cultural points of reference that an older generation still holds dear can be destabilizing enough to cause serious recoil. Historical issues which are not settled in a democratic and controlled manner can explode with uncontrollable effect. Conversely, if they are repressed for the social or political greater good, they can also lead to the parallel threat of festering quietly and weakening society from within. Anyone who witnessed the turbulence of the decommunization process in Ukraine during recent years can only urge caution and delicacy.

Eurasia Center events

Alya Shandra, Editor, Euromaidan Press: The push to reassess the legacy of historical figures that we are currently seeing around the world is understandable. Ukraine witnessed much the same processes after the country’s 2014 Euromaidan Revolution, when many figures from the Soviet pantheon were toppled, including a huge number of Lenin statues that had survived the Soviet collapse. These communist-era statues served as visual markers of the country’s totalitarian past at a time when this past was being weaponized by Russia to resurrect its former empire. Their removal was emblematic of Ukraine’s choice to pursue a future as part of the Western world.

Unlike the toppling of statues currently taking place in other countries, the removal of Ukraine’s Lenin monuments was largely mandated by law as part of the decommunization measures adopted after the Euromaidan Revolution. At the time, there was criticism that the process was conducted via “Soviet methods”, meaning that it was done too rapidly and with little public discussion. For those caught up in the revolutionary moment, it felt like the right thing to do. However, in hindsight, a more open and detailed public debate could have been very beneficial for Ukraine. For example, the push to remove monuments could have been used to inform modern Ukrainian society about Soviet atrocities. If this had been done, then perhaps fewer than one-third of Ukrainians would be nostalgic for the USSR, as one recent poll suggested. We might also have fewer social divisions based on the politics of memory.

Ukraine’s decommunization experience also serves as a reminder of a basic rule at the heart of memory politics – the removal of monuments creates a vacuum that begs to be filled. Who should occupy the empty pedestal? This is a discussion any society engaged in toppling outdated heroes must be ready to have.

Peter Zalmayev, Director, Eurasia Democracy initiative: Instead of consolidating Ukraine’s post-Soviet society, the country’s hasty decommunization process has only exacerbated its myriad tensions. It was perhaps naive to expect a different outcome, given that Ukraine remains deeply divided by conflicting interpretations of the past.

Any nation’s historical memory necessarily features a multiplicity of narratives and includes figures who are revered as heroes by some and denounced as villains by others. No figure is more polarizing in Ukraine than nationalist icon Stepan Bandera. While Lenin monuments have been toppled by the hundred since 2014, statues of Bandera have gone up and streets have been renamed in his honor, including in Kyiv. Whatever one’s personal view of Bandera’s historical legacy, it is undeniable that his glorification, coupled with the wholesale destruction of totems of the Soviet past, has made Russian-speaking Ukrainians in the country’s east and south particularly susceptible to Moscow’s propaganda and wary of Ukraine’s post-Maidan trajectory. “Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater!”, the saying goes.

As Americans yearn to right historic wrongs and topple politically incorrect monuments, they must understand that the more rushed and chaotic the process, the less chance there is of any permanent healing and reconciliation. As Ukraine’s experience demonstrates, the US risks undermining national cohesion whilst in the grip of the current Jacobin zeal.

Peter Dickinson is the Editor of the Atlantic Council’s UkraineAlert Blog.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

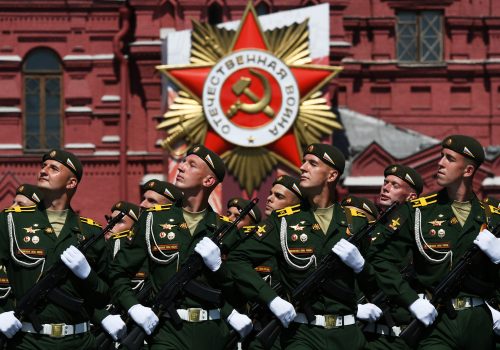

Image: A Lenin monument painted in the colors of the Ukrainian flag pictured in September 2014 in eastern Ukraine's Donetsk region. All of Ukraine's Lenin monuments were dismantled following the passing of decommunization laws in spring 2015. REUTERS/Gleb Garanich