Germany’s social democrats look for a new face, but their problems are much deeper

Key Points

- The SPD's own policies have led to falling numbers of traditional workers, the party's main base.

- At the same time, SPD is being squeezed from the political right and left over immigration and climate change policy

- The party must decide if they will pivot back left, remain in an uneasy alliance with Merkel's Christian Democrats, or attempt to appeal to the new workers of the 21st century

Since the end of the Second World War the social democratic parties of the center-left, together with the center-right Christian Democrats, have dominated national parliaments across Europe, creating political stability on the continent. In 2010 their fortunes began to shift, however, and across Europe social democrats found themselves defeated in national elections and competing with smaller parties to their right and left. In France, the Netherlands, and Czech Republic social democratic parties are down in the single digits. In Germany, one of the continent’s most important center-left parties the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) is reeling from back to back losses in national and European elections this year. In an effort to stall off total implosion, the SPD is seeking new leadership in a vote undertaken by individual party members rather than the party elite. But change at the top may not be enough to reverse SPD’s decline, as the party has failed to respond to structural changes within German society that have eroded support for the social democrats.

The German center-left collapses

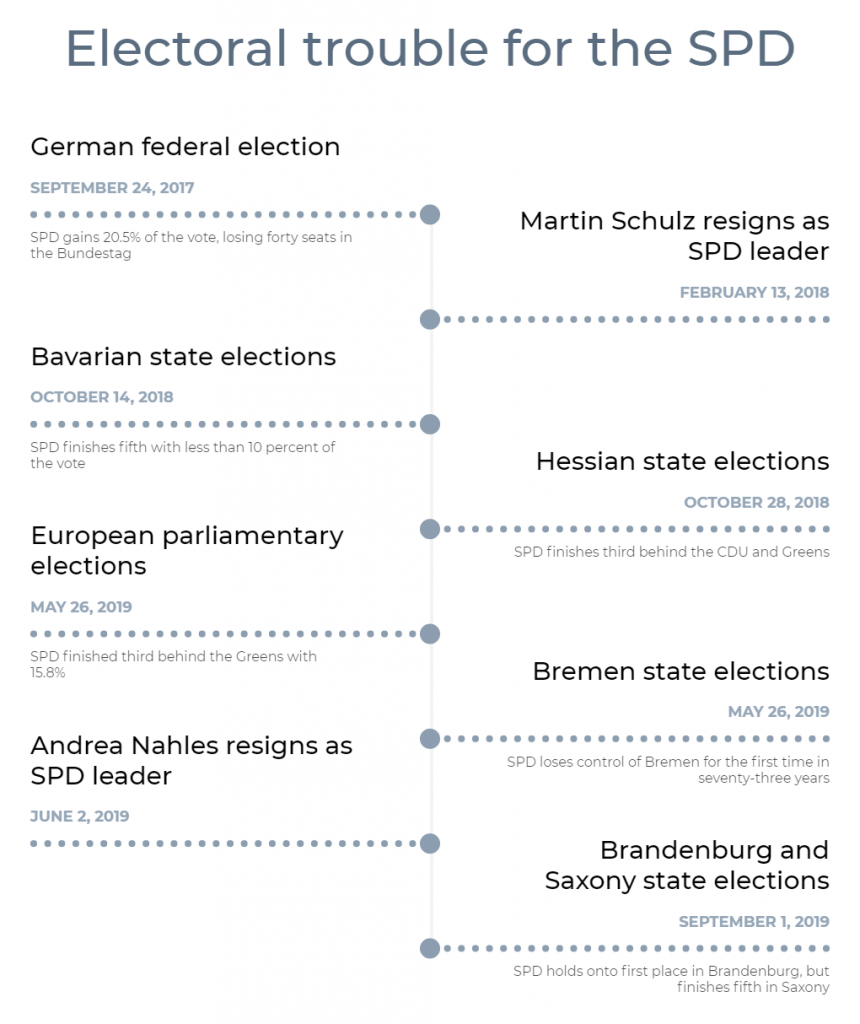

It is not an exaggeration to say that the SPD, like all of the European center-left, is in crisis. In 2002 the party gained the support of about 38 percent of the electorate; at the 2017 Federal election it got only 20.5% of the vote. In the 2019 European election of May 26, the German Green Party beat out the SPD with 20.5% compared to 15.8%. That same day, German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) defeated the SPD in Bremen, where the center-left party had held power for the last seventy-three years. The defeat in Bremen, compounded by a 2017 loss in Schleswig-Holstein devastated the party which had always counted on Northern Germany as a traditional stronghold of the center-left.

The string of defeats is unprecedented for Germany’s oldest political party, which traces its roots back to 1863 when, inspired by Karl Marx, the party was central to numerous social advancements including universal pensions and opening access to higher education. The SPD resisted the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s and was a vocal supporter of Ostpolitik in the 1970s that helped contribute to the Cold War detente in the 1980s.

But now it appears that the heyday of the SPD is past and the party is in serious trouble. The years of governing with Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in a ‘Grand Coalition’ (known colloquially as the GroKo in German) have now led the party to electoral disaster.

The resounding defeat at the recent European election forced out the SPD Leader Andrea Nahles, who resigned on June 2 both as party leader and head of the SPD’s Parliamentary group. Nahles had taken over from Martin Schulz, who was forced to resign after leading the SPD into a second GroKo following the 2017 federal election. Heralded as the left-wing reformer the party needed, Nahles was booted out as party leader after just over a year following poor results at the ballot box and an inability to stabilize a party without direction. The current search for a leader is seen as an attempt to stem the bleeding of the party and reinvigorate the membership, but it may not be enough to save the SPD.

A self-inflicted wound?

Once a big tent party of the center-left the last decade has been brutal for the SPD. In 1998 the party commanded 40 percent of the national vote, today the SPD would be lucky to reach half of that. The decline of the traditional working class in Germany, which formed the backbone of SPD support in the 20th century, is been coupled with the rise of a new group of workers, a digital precariat. These younger works are often highly educated and socially progressive, caring about the environment and viewing migration more positively than the traditional working class. Stuck in the gig economy they generally lack the job security of the classic worker and a reduced social safety net leaves them vulnerable. The have a very different take on the concept of justice, than more traditional workers.

How can one party be the home for both highly educated voters, working in a precarious new economy, as well as the traditional working class?

Meanwhile as classical industrial jobs fade away, ever larger numbers of more traditional German workers are cast aside. This is especially problematic in the east, where workers are often less educated and are less progressive on social issues than in western Germany. The changing nature of what it means to be a “worker” leaves the SPD is a serious bind. How can one party be the home for both highly educated voters, working in a precarious new economy, as well as the traditional working class?

Rather ironically this situation was, in part, created by the SPD. When the Red-Green coalition government of Gerhard Schroeder took over in 1998 the German economy was only just sputtering along and the Federal Republic was dubbed by The Economist as “the sick man of the euro” suffering from “a byzantine and inefficient tax system, a bloated welfare system, and excessive labor costs.” In response, Schroeder launched his Agenda 2010, which implemented cuts to the German welfare system and liberalized the labor market in an attempt to improve economic performance and reduce unemployment. As the Third Way Manifesto signed by both Schroeder and then British Prime Minister Tony Blair put it, these changes were necessary to “transform the safety net of entitlements into a springboard to personal responsibility.” In the Third Way, “part-time work and low-paid work are better than no work because they ease the transition from unemployment to jobs.” Technological advancements, a globalized economy, and the Agenda 2010 reforms created the German digital precariat, while at the same time alienating traditional workers, many of whom began fleeing to the far-left Die Linke party.

The next blow would come during the European migrant crisis that began in 2015. As Germany was inundated with migrants from North Africa and the Middle East the CDU-SPD coalition government pursued a policy of openness and integration with Angela Merkel proclaiming “Wir schaffen dass” (we can do it). This made Merkel an exception among western leaders who mostly turned a blind eye to the crisis. Although the Federal Republic did an excellent job integrating a million new arrivals and Germany needs the immigration to maintain a strong economy, the policy put off many traditional SPD voters who felt alienated by the amount of money the federal government was spending on refugees as opposed to needy Germans. This was especially the case in the former East Germany, where many people, despite the billions of Euros invested into the region, felt left behind. This caused an additional exodus of SPD voters, this time towards parties on the right of the political spectrum such as the Alternative for Germany (Alternativ für Deutschland –AfD). At the same time, Merkel has been steadily moving the CDU more into the center of the center-right, eating up issue positions once advocate by the center-left.

Finally, the issues occupying German voters’ minds has shifted away from the SPD’s turf. The Federal Republic has enjoyed ten consecutive years of economic growth, unemployment is at a record low, and wages are rapidly increasing. As such, a message oriented at social economic issues that would appeal in poorer parts of the country, rings hollow in wealthier parts of Germany. Meanwhile, parts of the Rhine River were closed during a summer of scorching heat in 2019, further highlighting the challenge of the climate crisis to an already sympathetic German electorate. Approximately 59 percent of Germans find that climate change in the most pressing problem facing Germany. The SPD has had a difficult time hitting the right notes on climate change—especially as a member of a coalition government accused of a lackluster response. As a result, the popularity of the Green Party has risen, whilst the SPD has continued to decline.

Finding a new face

In an attempt to regain momentum, the SPD has looked for changes at the top. For the first time since 1993, party members will select the party leader. While legally the leader of a German party has to be elected indirectly by party convention, SPD leaders will hold the member vote at the party convention, which will be seen by the party convention as politically binding. Although only one party leader is required by law, the SPD has encouraged joint mixed gender bids. Consequently, there are seven male-female pairs for the leadership, along with one single bid for the leadership race. The contenders are currently on a country wide “speed dating” tour of Germany, attending regional conferences to meet and appeal to party members. The first round of votes by members will be on October 14 and 25. If no ticket receives an absolute majority, the two tickets with the highest number of votes qualifies for the next round of voting. A quorum of 20 percent of the party membership is required to legitimate the vote. The Executive Board of the SPD will propose the winning ticket as the new leader at the party convention on December 6-8.

Many of the SPD’s more prominent leaders such as the extremely popular Malu Dreyer, minister-president of Rhineland-Palatinate, and Manuela Schwesig, minister president of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, shied away from the contest. Most prominent among the candidates is Finance Minister Olaf Sholz who is in a co-leadership bid with Klara Geywitz, a little-known member of parliament from eastern Germany.

Sholz and Geywitz are running on a platform that includes remaining in the Grand Coalition, a position shared by the next most prominent challenger, moderates European Affairs Minister Michael Roth and Christina Kampmann, who served as state minister for families, children, youth, culture, and sport in North Rhine-Westphalia from 2015-2017. Preserving the Grand Coalition is not popular with many in the SPD, especially within the SPD’s Youth Group led by Kevn Kühnert. The favorite bid of Kühnert is Norbert Walter-Borjans and Saskia Esken. Walter-Borjans carved a name for himself in German politics when as finance minister of North Rhine-Westphaia he pursued tax evaders with Swiss bank accounts. Walter-Borjans and Esken bid have have questioned the utility of the Grand Coalition, along with other farther left candidates Ralph Stegner and Gesine Schwan. Esken told Der Spiegel on the record that the grand coalition should not be a regular occurrence. In her opinion, the SPD needs to demonstrate vision and leadership, not consistent compromise with the center-right. In many ways the discussion in the SPD mirrors that within the US Democratic Party with more centrist candidates fending off progressive pairs intent on returning the SPD to its labor-oriented roots.

Searching for salvation

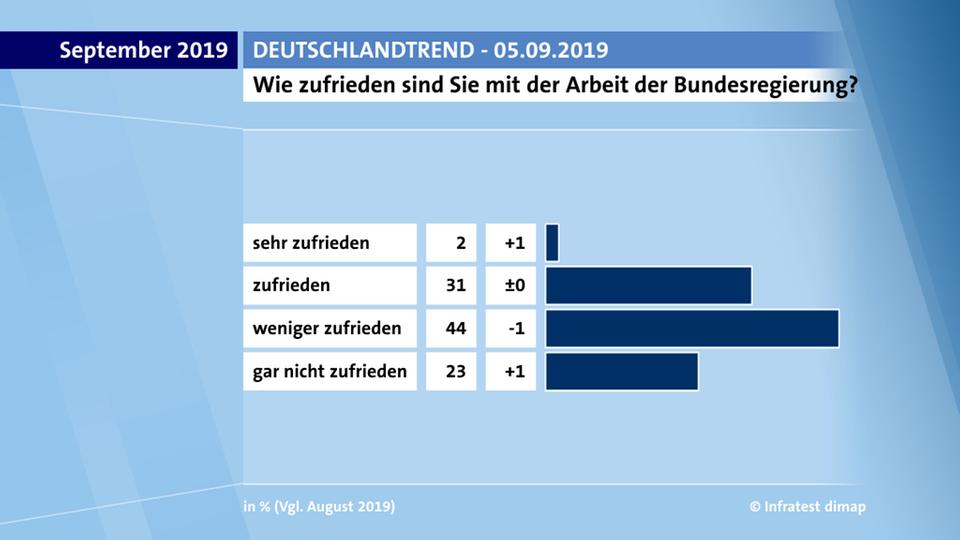

Despite the dislike of the Grand Coalition in the SPD, the Coalition Government has been highly productive. A recent survey by the Bertelsman Foundation found that in the first fifteen months of rule the government fulfilled or substantially addressed more than 60 percent of its promises. Despite this, the coalition is not popular across the political spectrum. An astounding 79 percent of those questioned believe that the Grand Coalition has only addressed “hardly any” or “about half” of the promises in the Coalition Agreement. In a second survey conducted in early September, 67 percent of those questioned said they were not satisfied with the performance of the government, with only 33 percent content with the Grand Coalition’s work to date.

Most interesting for those in the SPD that want to leave the coalition is voters’ views of party performance in the GroKo. Whilst 35 percent of citizens are satisfied with the job of the CDU in government, only 23 percent feel the same about the SPD. Worryingly, the number for the SPD is four points down from October 2018 and seven points up for the CDU. Clearly the GroKo is not working to the SPD’s advantage. German voters, however, paradoxically want the CDU/CSU-SPD coalition to remain in power until the end of the current legislative period in September 2021. For the SPD, the trend of polling suggests this is not a good idea, but what course the SPD takes very much depends on the next leader. Depending on the predilection of the leadership team, the party has a few options.

The first option available is to stay the course, which is the most likely outcome if Scholz and Geywitz wins the leadership. But all of the data indicates that the GroKo is damaging the SPD. German voters attribute success in the GroKo to the CDU/CSU and the SPD is viewed as neoliberal sellouts creating a serious credibility problem that has caused them to lose voters to both ends of the political spectrum. Leaving the GroKo, as those on the more left wing of the party want, may allow the SPD to start to rebuild the brand, but the question is, in what direction might the new SPD brand develop?

A second option is a hard turn to the left. This is the course advocated by some including Kevin Kühnert of the SPD Youth Group. Kühnert has called for the collectivization of large German companies, such as BMW, and for limits on private ownership of real estate. Without such moves, according to Kühnert, “overcoming capitalism” will be impossible. These views, however, are not widely popular in Germany and the party adopting such positions makes about as much sense as staying in the GroKo. There is no evidence in polling that suggests these ideas would be welcomed by a large part of what is a generally prosperous Germany society. In fact, such a move would most likely cause the remaining support for the party to collapse.

The final option would be to reinvent the party for the 21st century worker. Trying to return to the traditional party base is difficult given the decline of traditional workers. Given that traditional jobs continue to decline and that many of these voters are older, the smarter bet seems to be navigating a position that more accurately reflects the concerns of younger workers in the new economy. This approaches builds on the present and the future, not the past. An agenda oriented around economic, social, generational, and environmental equity, and delivered as the main opposition party, may be enough to start reinvigorating what’s left of the SPD. Instead of compromise after compromise with the Union in coalition, the SPD can hammer the CDU/CSU on these areas of concern, rebuilding credibility and stalling off total irrelevance.

Given the structural changes in German society and the economy, the SPD will most likely never regain the same size share of the vote as they had at the turn of the century, but if the party can climb back to the high twenties/low thirties in the polls, it would be a triumph in and of itself. These numbers, when coupled with a larger vote share for the Greens, would mean that it might then be possible to form a Green-SPD coalition that may serve both parties well. Whichever direction the party chooses this autumn, social democrats across Europe will be watching closely to see what course one of Europe’s most prestigious parties chooses to chart.

Professor Michael John Williams is director of the Program in International Relations at New York University.

Further reading:

Image: German Social Democratic Party (SPD) Finance Minister Olaf Scholz and SPD supporters react after first exit polls for the Brandenburg state election in Potsdam, Germany, September 1, 2019. REUTERS/Christian Mang