FAST THINKING: Is the Iraq War over… again?

JUST IN

First Afghanistan, now Iraq. Seven years after US troops returned to the country to fight ISIS, US President Joe Biden and Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi announced on Monday that the American combat mission in Iraq will wrap up by year’s end. As the US military formally transitions to an advisory role with Iraqi forces, what’s next for the fights against ISIS and Iran-backed militias? Will anything really change? Our Iraq experts weigh in.

TODAY’S EXPERT REACTION COURTESY OF

- Kirsten Fontenrose: Director of the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative and former US National Security Council senior director

- Andrew Peek (@AndrewLPeek): Nonresident senior fellow and former deputy assistant secretary for Iran and Iraq at the US State Department

- Abbas Kadhim (@DrAbbasKadhim): Director of the Iraq Initiative

The more things change…

- It’s natural to compare Biden’s simultaneous military pullouts in Iraq and Afghanistan. But Kirsten says that in contrast to the full withdrawal from Afghanistan, “in Iraq the drawdown is more of a rebalancing, removing fighting forces and replacing them with trainers who will continue to build the capacity of Iraqi security services.”

- Andrew calls the announcement “useful diplomatic sleight of hand” for the Biden administration. “Of course the US should be advising the Iraqis, and not sending combat troops on patrols through Baghdad. But they don’t [patrol Baghdad] now.”

- What will likely remain, Andrew predicts, are the most important elements of the existing mission: “high-end [US special operations] capabilities” and “US military engagement with Iraqi forces and Iraqi politicians. … All of that can be done under the rubric of an advisory mission, or whatever is most useful for Kadhimi and the administration to call it.”

- Zooming out, Kirsten foresees China, Russia, and Iran arguing that the Afghanistan and Iraq withdrawals “signal that the US is not the best choice for a strategic partner.” But the US government has poured resources into Iraqi and Afghan security forces “so that they can have a chance, if they choose, to protect their own countries,” she notes, whereas the Chinese, Russian, and Iranian governments wouldn’t “be willing to do that; they prefer the security services of countries they work with to be weak so their influence and resource-exploitation goals in the country cannot be challenged.”

Subscribe to Fast Thinking email alerts

Sign up to receive rapid insight in your inbox from Atlantic Council experts on global events as they unfold.

Wild cards to watch

- Kirsten advises keeping an eye on the “Iran-aligned Popular Mobilization Forces (PMFs) in Iraq, nominally part of the Iraqi security services but more loyal to Tehran than Baghdad.” These are the groups that the United States recently bombed.

- While the US withdrawal “will inevitably be interpreted as a win,” for the PMFs, Kirsten tells us, they “may see this announcement as merely window dressing without a meaningful reduction in the size of the US footprint; the uniforms change, the numbers don’t.”

- US special operations forces will be much more limited in what they’re authorized to do after this withdrawal is complete, Kirsten contends, but that might not stop the PMFs from attacking Americans. “In that case,” she asks, “is the US simply putting more service members with less ability and authority to defend themselves in the same danger US combat troops have faced?”

Politicking in Baghdad

- “There are several [political] players in Iraq who will not be satisfied with less than a full withdrawal of all US military presence, including contractors and trainers,” Abbas says. But “the Iraqi government must make it clear to its domestic political partners and to the Iraqi public that any proposal to put Iraqi security forces in complete responsibility will have to include serious measures for training, equipping, and capacity-building, which have to be provided by international allies.”

- Andrew says that while Kadhimi has tried to take on Iran-backed militias, this deal signals that “he needs either a sop to the Iran-aligned political factions in the country to retain their blessing for his appointment or needs this deal to obviate a more forceful parliamentary action” such as evicting the US military altogether.

- Monday’s announcement, according to Kirsten, “was undoubtedly timed to get in front of Iraqi parliamentary elections” in October and avoid placing Kadhimi in the bind of having to enforce a parliamentary vote expelling American forces he relies on. This week’s agreement among US and Iraqi leaders, she explains, “preserves the prime minister’s standing and allows the US to shape its drawdown to the liking” of US Central Command and Iraqi forces.

- Abbas forecasts that putting aside contentious issues involving the American military presence in the country will improve US-Iraqi diplomatic relations, which have started to flower beyond the longtime concerns of troops and oil. “A noticeably deep discussion on bilateral cooperation on economics, education, and cultural exchange,” he says, will help define the future of the relationship.

Further reading

Mon, Jul 26, 2021

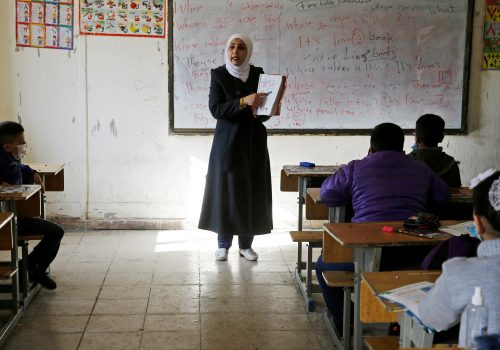

An “illiterate generation”—one of Iraq’s untold pandemic stories

MENASource By

The devastating impacts of COVID-19, coupled with years of spillover effects of violent conflict and extremism, have already proved to be detrimental to students whose education and future career ambitions already receive limited attention.

Mon, Jun 28, 2021

FAST THINKING: What Biden’s airstrikes left behind

Fast Thinking By

What does this mean for the future of drone warfare and the US military presence in Iraq? Our experts sort through the fallout.

Wed, Mar 3, 2021

How to normalize the Iraq-Iran relationship

MENASource By Andrew L. Peek

Of course, no country exists in a vacuum, but there are certain clarifications of the relationship between the two countries that every Iraqi should support—and Americans should insist upon.

Image: A US soldier is seen during a handover ceremony of Taji military base from US-led coalition troops to Iraqi security forces, in the base north of Baghdad, Iraq, on August 23, 2020. Photo by Thaier Al-Sudani/Reuters.