Entangling alliances? Europe, the United States, Asia, and the risk of a new 1914

Introduction

As Russia invades Ukraine, China threatens Taiwan, Iran harasses the Gulf States, and Turkey’s neighbors worry about Ankara’s designs, it is a good time to reassess the validity of alliances for global security.

Some believe that traditional military alliances are getting weaker or outmoded, and will increasingly be replaced by looser ad hoc groupings such as the Quad,1The Quad involves Australia, India, Japan, and the United States. the defense-alliance trio known as AUKUS, or coalitions for given operations such as those in Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, or Libya. After all, isn’t the US Secretary of State’s own rock band called Coalition of the Willing?

This author was wrong when he surmised in 2004 that “permanent multinational alliances appear increasingly to belong to the past.”2Bruno Tertrais, “The Changing Nature of Military Alliances,” The Washington Quarterly 27, no. 2 (2004), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1162/0163 66004773097759. He was not alone. In 2007, Rajan Menon predicted “the end of alliances.”3Rajan Menon, The End of Alliances (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). In 2008, Parag Khanna thought that states now operated “in a world of alignments, not alliances.”4Paragh Khanna, The Second World: Empires and Influence in the New Global Order (New York: Random House, 2008). Likewise, in 2009, Stephen Walt wrote that the United States would rely more heavily on ad hoc coalitions and bilateral arrangements.5Stephen M. Walt, “Alliances in a Unipolar World,” World Politics 61, no. 1 (2009). Thomas Wilkins concurred with Khanna and wrote in 2012 that informal security arrangements (“alignments”) would be the future international security standard.6Thomas S. Wilkins, “‘Alignment,’ not ‘Alliance’: The Shifting Paradigm of International Security Cooperation: Toward a Conceptual Taxonomy of Alignment,” Review of International Studies 38, no. 12 (January 2012), https://www.jstor.org/stable/41485490.

In fact, standing alliances are proliferating (increasing in numbers), widening (welcoming new members), and deepening (reinforcing solidarity and cooperation). The result is a network of interlocking defense relationships, to which an ever-thicker layer of new security groupings and quasi alliances is being added.

Yet alliances will increasingly be tested. As alliances are created or reinforced, adversaries react and probe their limits. This, in turn, may lead to what political scientists call “bandwagoning,” or rallying behind a protector. This dynamic will increase as both neoimperial behaviors develop and as the scope of contested spaces expands—at sea, in cyberspace, and in outer space.

Will this expanding network of alliances create more stability or more instability? Does alliance proliferation reduce or increase the risk of war? And if war erupted somewhere, what would be the risks of escalation?

A definitive answer may be impossible to arrive at, but evidence suggests that the current proliferation of alliances is, on balance, more stabilizing to world order than not. There is no need for complacency. The emerging system is complex, and policymakers would do well to think through possible future crises by imagining how the various moving parts would end up interacting.

That said, most of our mental maps of how alliances should work are shaped by living memory of the Cold War, and the comparatively stable and predictable bipolar order that emerged during that time period. The dawning multipolar world, featuring an increasingly dense network of security arrangements, uncomfortably reminds us of the years 1912- 1914, shortly before the outbreak of World War I. Analysts worry that the impenetrable web of obligations may put us on a “conveyor belt” to conflict.7See Roger Cohen, “Yes, It Could Happen Again,” Atlantic, August 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/08/yes-it-could-happenagain/373465/; Ja Ian Chong and Todd H. Hall, “The Lessons of 1914 for East Asia Today: Missing the Trees for the Forest,” International Security 39, no. 1 (2014), https://direct.mit.edu/isec/article-abstract/39/1/7/12289/The-Lessons-of-1914-for-East-Asia-Today-Missing?redirectedFrom=fulltext; and Richard N. Rosecrance and Steven E. Miller, eds., The Next Great War? The Roots of World War I and the Risk of US-China Conflict (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2014).

The resilience of alliances

The term “alliance” is of broad usage, often used alongside expressions such as “strategic partnership” or “defense agreement.”

There are two broad possible definitions of what an alliance is.8This paper refers only to permanent or standing alliances, not ad hoc or temporary coalitions. In the strictest definition, it refers to an explicit defense commitment—whether it is treaty-based or more informal—that involves a positive security guarantee or a promise of military assistance in case a country is attacked. This excludes US partnerships with “major non-NATO allies,” a badly named category of arrangements designed to facilitate security assistance and arms transfers but that does not entail any defense commitment to the designated country.9US Department of State, “Major Non-NATO Ally Status,” Fact Sheet, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, January 20, 2021, https://www.state.gov/major-nonnato-ally-status/. This definition of alliance also excludes collective security organizations such as the Organization for the Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), as well as groupings such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).10Vali Kaleji, “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization Is No ‘New Warsaw Pact’ or ‘Eastern NATO,’” National Interest, November 13, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/shanghai-cooperation-organization-no-%E2%80%98new-warsaw%E2%80%99-or-%E2%80%98easternnato%E2%80%99-196138. The same goes for concepts such as an “alliance of democracies” once promoted by US President Joe Biden.11Joe Biden, “Democracy in an Age of Authoritarianism,” Remarks by then-Vice President Biden, Copenhagen Democracy Summit, June 22, 2018, https://www.allianceofdemocracies.org/speech-by-joe-biden/. One of the crispest definitions of an alliance was put forth by political scientist Robert Osgood: “a latent war community.”12Robert E. Osgood, Alliances and American Foreign Policy (Washington: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1968), 19.

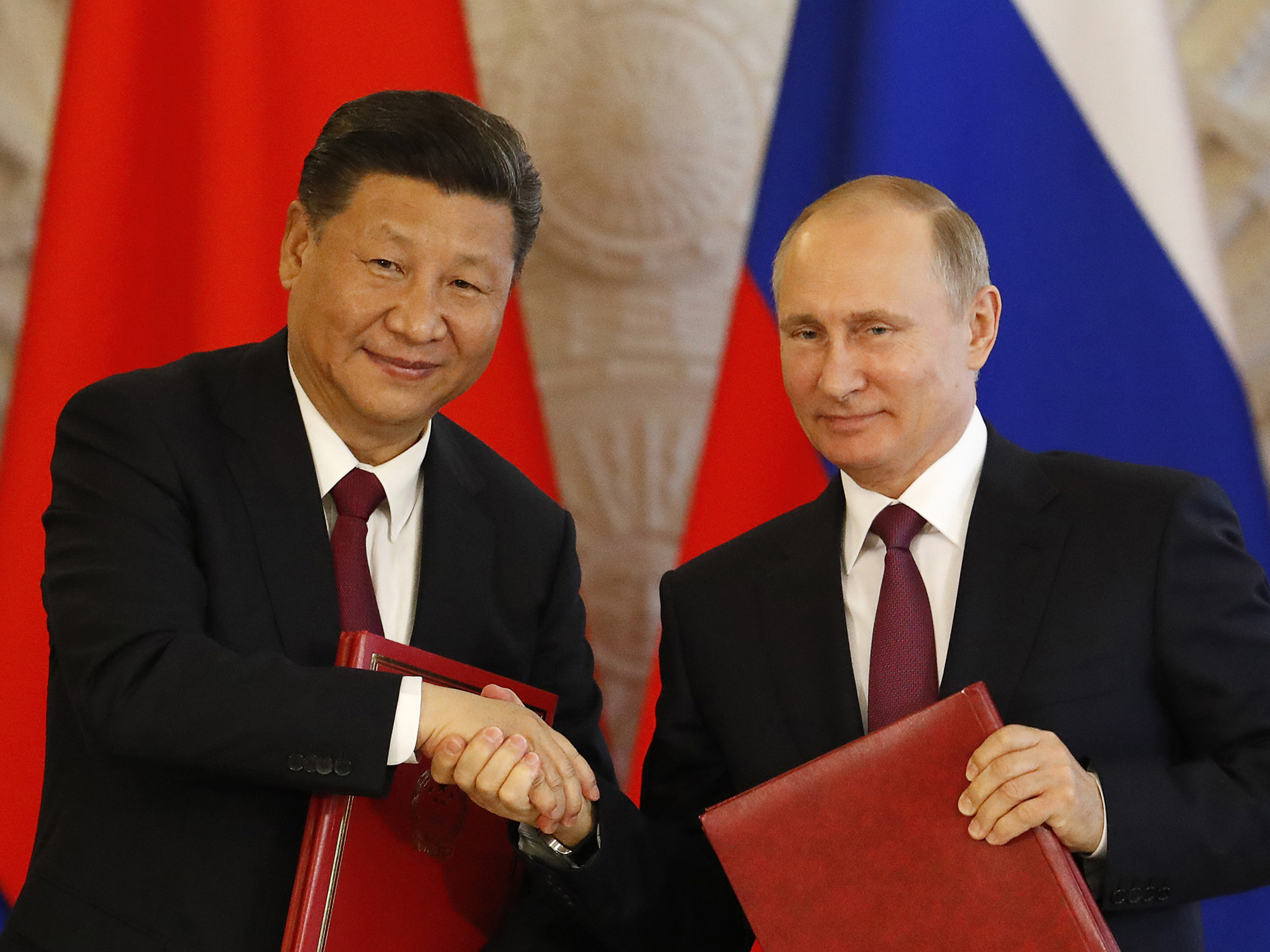

A second, broader definition includes close defense partnerships which do not include a security guarantee but may nevertheless be interpreted by at least one of the parties—an ally or an adversary—as quasi alliances. Walt calls an alliance “a formal or informal arrangement for security cooperation between two or more sovereign states.”13Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1987), 12. This category includes the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) involving Australia, India, Japan, and the United States (described by Delhi as a “nonmilitary alliance”), as well as the network of French Indo-Pacific partners once described as an “alliance” by French President Emmanuel Macron.14Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “To Smoothen Ruffled Feathers in Asia, India Terms QUAD a Nonmilitary Alliance,” Economic Times, September 22, 2021, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/to-smoothen-ruffled-feathers-in-asia-india-terms-quad-a-non-military-alliance/articleshow/86415597. cms; Emmanuel Macron, Discours du Président de la République à la Conference des Ambassadeurs, Office of the President of France, August 27, 2019, https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2019/08/27/discours-du-president-de-la-republique-a-la-conference-des-ambassadeurs-1. It also includes the Russia-China partnership, sometimes explicitly described by Russian authorities as an “allied relationship” and the two as “allies”—while Beijing likes to claim this relationship is “better than an alliance.”15President of Russia, “Valdai Discussion Club Session,” October 3, 2019, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/61719; Tass, “Russia, Chinese Presidents to Discuss NATO’s Belligerent Rhetoric, Says Kremlin Spokesman,” December 14, 2021, https://tass.com/politics/1375233; and Laura Zhou, “Russia Relationship Better Than an Alliance, Foreign Minister Says,” South China Morning Post, July 12, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/ diplomacy/article/3140798/russia-relationship-better-alliance-chinese-foreign-minister. The difference is qualitative more than quantitative: some security partners cooperate more than formal defense allies.

Since the end of World War II, alliances, however you define them, have proven to be quite resilient. The official list of formal US collective defense commitments includes treaties signed with countries of the American continents (Rio, 1947), Europe and Canada (Washington, 1949), Korea (1951), Australia and New Zealand (1951), the Philippines (1951), Japan (1951, 1960), and members of the largely forgotten but still valid South-East Asia Treaty (the Manila Pact of 1954).16US Department of State, “US Collective Defense Arrangements,” (Treaty Affairs, Archived Content 2009-2017, https://2009-2017.state.gov/s/l/treaty/ collectivedefense/index.htm). Two Asian countries that are members of the Manila Pact are also covered by other US commitments (the Philippines by treaty, Thailand through the Rusk-Thanat Communiqué of 1962). Pakistan withdrew from the (now defunct) South-East Asia Treaty Organization, or SEATO, in 1968 and no longer appears on the list of Manila-Pact-related US defense commitments. Expert Alexander Lanoszka calls the South-East Asia Treaty a “zombified alliance.” See Alexander Lanoszka, Military Alliances in the Twenty-First Century (London: Polity Press, 2022), 176. To this list can be added Taiwan, the Gulf States, as well as Israel—countries that do not benefit from treaty-based commitments but for which repeated and explicit statements by US presidents amount to de facto security guarantees.17Neither Israel nor the United States was ever interested in forging a true defense pact. As per Saudi Arabia, US presidents have used language such as “the United States is interested in the preservation of the independence and territorial integrity of Saudi Arabia. No threat to your Kingdom could occur which would not be a matter of immediate concern to the United States.” See President Truman to King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia, 711.56386A/10–3050, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1950, V, The Near East, South Asia, and Africa, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/ frus1950v05/d658.

While the United States has the largest number of inherited security commitments that persist to this day, there are several others worth considering. European countries remained bound together by the Modified Brussels Treaty of 1954 until it was subsumed in the Lisbon Treaty. Less known is the fact that sixteen UN members (including seven NATO countries) also remain committed to the defense of Korea through a 1953 declaration stating that they would “again be united and be prompt to resist” should the armistice break down.18Declaration of the Sixteen Nations Relating to the Armistice, July 27, 1953, https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8100/CBP-8100.pdf. China, for its part, has a long-standing commitment to the security of North Korea. Finally, the Arab League’s mutual defense commitment still exists on paper, though it has not proven very efficient since its signature in 1950.19Treaty of Joint Defense and Economic Cooperation between the States of the Arab League, June 17, 1950, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/ arabjoin.asp.

To be sure, there have been dents in the web of legacy alliances. Those forged by the Soviet Union have disappeared. The Warsaw Pact was disbanded in 1991. The USSR’s Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance with North Korea (1961), which involved a defense commitment, was replaced in 2000 by a Treaty on Friendship, Good Neighborliness and Cooperation, which includes a mere commitment not to side with any attacking party.20“Russia and North Korea Sign Friendship Treaty,” Monitor vol. 6, no. 30 (February 2000), Jamestown Foundation (defunct publication), https://jamestown.org/program/russia-and-north-korea-sign-friendship-treaty/.

Western alliances have not been immune to shocks and tensions either. Due to Wellington’s antinuclear stance, the United States withdrew its alliance obligations to New Zealand under the ANZUS Treaty in 1986. Mexico, for its part, withdrew from the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance—the Rio Treaty—in 2002 to protest against US foreign policy. In addition, the four countries of the “Bolivarian Alliance” (Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, and Venezuela) announced their withdrawal in the early 2010s, although they never formally went further. More recently, President Donald Trump questioned whether Washington should defend the “tiny” and “aggressive” small country of Montenegro, NATO’s latest admitted member.21Amanda Macias and Tucker Higgins, “Trump Says Defending Tiny NATO Ally Montenegro Could Result in World War III,” CNBC, June 18, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/07/18/trump-defending-nato-ally-montenegro-could-result-in-world-war-3.html. President Macron famously wondered whether the Alliance was in danger of “brain death.”22Emmanuel Macron Warns Europe: NATO Is Becoming Brain-dead,” Economist, November 7, 2019, https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/11/07/ emmanuel-macron-warns-europe-nato-is-becoming-brain-dead. Recent spats between Turkey and its allies have led many wondering whether Ankara would, or should, remain a member of NATO. Meanwhile, France updated its own defense agreements with eight former African colonies, no longer committing itself to automatically defend seven of them (the outlier being Djibouti).23Jean-François Guilhaudis, “Les accords de ‘défense’ de deuxième génération, entre la France et divers pays africains,” Centre d’études sur la sécurité internationale et les coopérations européennes, June 1, 2021, https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01978366.

That said, most pre-1990 defense guarantees have overall proven remarkably resilient.24Some legacy defense commitments (e.g., US-Liberia agreements of 1942 and 1943) are not mentioned here. Alliances are regularly described as being “in crisis.” Yet as Alexander Lanoszka puts it, “dysfunction is a permanent feature of alliance politics, not a temporary bug.”25Lanoszka, Military Alliances, 193.

US alliances were successfully tested in 2001. NATO’s Article 5 was invoked for the first time ever. It was not a given that the Alliance would survive the Iraq War and major transatlantic crises such as the Snowden affair. The Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance—the Rio Treaty—was also invoked in 2001, as well as in 2019 (regarding the situation in Venezuela).26Congressional Research Service, “The Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance and the Crisis in Venezuela,” Insights (series), Version 8, Updated December 11, 2019, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11116. It was not a given either that the US-Saudi defense relationship would have survived 9/11 and Jamal Khashoggi’s murder, or that the US-Turkey alliance would survive the acquisition by Ankara of modern Russian air defense systems. Nor was it a given, more generally, that US alliances would survive the Obama and Trump eras, when attention given to most allies was less important than it had been in the past. During the presidency of Donald Trump, the number of US troops in Europe increased and NATO welcomed two new members (Montenegro and North Macedonia). In fact, two scholars suggest that when seen in a historical perspective, US-based alliances tend to last twice as long as non-US-based ones, and that the main treaty-based American alliances forged after 1945 are historical outliers in terms of their duration.27Mark S. Bell and Joshua D. Kertzer, “Trump, Psychology, and the Future of US Alliances,” in Assessing the US Commitment to Allies in Asia and Beyond, ed. Sharon Stirling, German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2018, https://www.gmfus.org/sites/default/files/ Assessing%2520the%2520US%2520Commitment%2520to%2520Allies%2520in%2520Asia%2520and%2520Beyond_0_0.pdf.

China, meanwhile, has twice renewed (in 2001 and 2021) its own 1961 Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance with North Korea—its sole formal defense commitment.28Khang Vu, “Why China and North Korea Decided to Renew a 60-year-old Treaty,” Interpreter (commentary and analysis site), Lowy Institute, July 30, 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/why-china-and-north-korea-decided-renew-60-year-old-treaty. Khang Vu, “Why China and North Korea Decided to Renew a 60-year-old Treaty,” Interpreter (commentary and analysis site), Lowy Institute, July 30, 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/why-china-and-north-korea-decided-renew-60-year-old-treaty.

The deepening and expanding of formal alliances

The NATO Alliance has welcomed fourteen new members since 1990, nearly doubling its membership. After three decades of absence, France rejoined NATO’s military command structure in 2009. After focusing on peace support and counterterrorism operations for twenty years, NATO renewed its focus on collective defense vis-à-vis Russia, and is currently reviewing what the rise of China means for the Alliance’s security. Importantly, Alliance members have also made it clear that beyond terrorism, other forms of nontraditional aggression, in cyberspace (2014) as well as “to, from, or within outer space” (2021) could qualify as an armed attack and trigger Article 5.29Wales Summit Declaration Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the North Atlantic Council in Wales, September 5, 2014, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_112964.htm; and Brussels Summit Communiqué Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the North Atlantic Council in Brussels, June 14, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_185000.htm.

The Alliance also has developed a web of security partnerships with many countries: fifteen “partners for peace,” seven members of the Mediterranean Dialogue, four Gulf countries of the Istanbul Cooperation Initiative, as well as nine “partners across the globe.” Sweden, Finland, Ukraine, and Georgia have joined the NATO Response Force.30“Sweden to Join NATO Response Force and Exercise Steadfast Jazz,” NATO, Newsroom (website), October 14, 2013, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/ news_104086.htm. NATO is increasingly projecting its security umbrella over European nonmembers. As early as 1991, NATO allies declared that “the consolidation and preservation throughout the continent of democratic societies and their freedom from any form of coercion or intimidation are therefore of direct and material concern to us.”31“Partnership with the Countries of Central and Eastern Europe,” Statement, North Atlantic Council Meeting in Ministerial Session in Copenhagen, June 6-7, 1991, NATO Online Library, https://www.nato.int/docu/comm/49-95/c910607d.htm. Finland and Sweden have applied to NATO membership given the war in Ukraine, and were given security guarantees by several Alliance members to ensure their protection in the interim period. Measured in terms of intensity of relations, in the 2010s Ukraine became the number one NATO partner by a large margin.32Branislav Mičko, “NATO between Exclusivity and Inclusivity: Measuring NATO’s Partnerships,” Czech Journal of International Relations 56, no. 4 (2021), https://mv.iir.cz/article/view/1746. Whatever the outcome of the Russian invasion, NATO will likely have to provide some form of security guarantees for the Ukraine that emerges on the other side. Separately, the United States is also bolstering its defense cooperation with key NATO allies in the South (Greece) and in the North (Norway, Denmark).33Humeyra Pamuk, “Blinken Says Renewed US-Greece Defense Deal to Advance Stability in Eastern Mediterranean,” Reuters, October 15, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/greece-says-renewed-defence-deal-with-us-protect-sovereignty-both-2021-10-14/; US Department of State, US-Norway Supplementary Cooperation Agreement, April 16, 2021, https://www.state.gov/u-s-norway-supplementary-defense-cooperation-agreement/; and “Denmark Talks on Hosting US troops Not Triggered by Ukraine Crisis: PM,” Reuters, January 10, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/denmark-us-begintalks-new-defence-agreement-2022-02-10/.

In addition, the Treaty of Lisbon (2007) commits EU members to collective defense through Article 42.7.34Article 42.7 no longer binds the United Kingdom, which has left the EU. This is inherited from the aforementioned Modified Brussels Treaty of 1954. While the obligation is generally considered secondary given that most concerned countries are members of NATO, Article 42.7 was nevertheless activated by France after the terrorist attacks of November 2015 in Paris. Contrary to NATO’s Article 5, the EU’s Article 42.7 does not require consensus: any EU country can invoke it to support an attacked member. Intra-European defense solidarity was further reinforced by two new bilateral defense clauses: one between Germany and France through the Aachen Treaty of 2019 (which includes a particularly strong mutual commitment), and another between Greece and France through a strategic partnership agreement signed in 2021.35John Psaropoulous, “Greece Ratifies Landmark Intra-NATO Defence Pact with France,” Al Jazeera (website), October 7, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/ news/2021/10/7/greece-ratifies-intra-nato-defence-pact-with-france. These countries are thus now protected by concentric circles of alliances resembling a set of matryoshka dolls. For countries that are members of both the European Union and NATO, Article 42.7 is a sort of “backstop” in case consensus could not be achieved within the North Atlantic Council (NAC) to trigger Article 5; and the France-Greece agreement is a backstop for Greece in case 42.7 could not be invoked. Note also that the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) includes a “solidarity clause” (Article 222) that can be invoked in case of terrorist attack. On top of these two agreements, Paris increasingly recognizes now that its nuclear deterrent has a de facto European dimension and thus protects its neighbors’ vital interests.36Emmanuel Macron, Speech of the President of the Republic on the Defense and Deterrence Strategy, February 7, 2020, https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2020/02/07/speech-of-the-president-of-the-republic-on-the-defense-and-deterrence-strategy. Additionally, Paris and London have recognized since 1995 that their own vital interests are nearly identical, paving the way for mutual nuclear defense.37Bruno Tertrais, Entente Nucléaire: Options for UK-French Nuclear Cooperation, Discussion Paper 3, Basic Trident Commission, British-American Security Information Office, June 2018, https://basicint.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/entente_nucleaire_basic_trident_commission.pdf.

Alliances have also been bolstered outside of Europe. In 2010, Washington instituted an in-depth Extended Deterrence Dialogue with Japan, and in 2016, an Extended Deterrence Strategy and Consultation Group with Korea.38US Department of State, “United States-Japan Extended Deterrence Dialogue,” Press Release, Office of the Spokesperson, April 30, 2021, https://www.state.gov/united-states-japan-extended-deterrence-dialogue/; and Chang Jae-soon, “S. Korea, US Agree to Launch High-level ‘Extended Deterrence’ Dialogue,” Yonhap News Agency, October 20, 2016, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20161019010455315. Since 1996, US officials have made it clear that the contested Senkaku islands (called Diaoyu by China) were covered by the US-Japan security treaty. This was for the first time confirmed at the presidential level by Barack Obama, orally, in 2014, and then more solemnly by Donald Trump, in writing, in 2017.39Brian Victoria, “The Shifting US Position over the Senkaku Islands,” East Asia Forum, November 13, 2020, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/11/13/theshifting-us-position-over-the-senkaku-islands/. The Trump administration also bolstered its commitment to the Philippines, making it clear that an attack against Filipino forces in the South China Sea would be covered by the 1951 treaty—a stance that was affirmed by the Biden administration; the two countries are currently discussing a possible modification of the existing treaty.40Renato De Castro, “Washington’s Changing Position on the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty,” BusinessWorld, September 28, 2021, https://www.bworldonline.com/washingtons-changing-position-on-the-1951-mutual-defense-treaty/; and Associated Press, “US, Philippines Assessing Defense Treaty, China Wary,” September 30, 2021, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/rest-of-world/us-philippines-assessing-defense-treaty-china-wary/articleshow/86651005.cms. The United States is also reinforcing its defense cooperation with Australia, and both countries now agree that their alliance is also valid for defending against cyberattacks.41US Department of State, “Joint Statement on Australia-US Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) 2021,” Press Release, Office of the Spokesperson, September 16, 2021, https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-australia-u-s-ministerial-consultations-ausmin-2021/; “ANZUS 2.0.: Cybersecurity and Australia-US Relations,” Special Report, Australian Security Policy Institute, April 2012, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/161646/SR46_cybersecurity_v2.pdf. Finally, the Biden administration has clearly confirmed that it would defend Taiwan against mainland China, rhetorically putting the island on a par with countries protected by treaty-based obligations.42David Brunnstrom, “US Position on Taiwan Unchanged Despite Biden Comment: Official,” Reuters, August 20, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asiapacific/us-position-taiwan-unchanged-despite-biden-comment-official-2021-08-19/. The consolidation of the Western system of alliances in Asia was made even stronger in 2021, when Australian and Japanese officials made it clearer that their countries would support the United States in a conflict over Taiwan.43Reuters, “‘Inconceivable’ Australia Would Not Join US to Defend Taiwan: Australian Defence Minister,” November 13, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/ world/asia-pacific/inconceivable-australia-would-not-join-us-defend-taiwan-australian-defence-2021-11-12/; Reuters, “Japan Deputy PM Comment on Defending Taiwan if Invaded Angers China,” July 6, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/japans-aso-peaceful-solution-desirable-any-taiwancontingency-2021-07-06/; and Jeffrey W. Hornung, “Taiwan and Six Potential New Year’s Resolutions for the US-Japanese Alliance,” War on the Rocks, January 5, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/01/taiwan-and-six-potential-new-years-resolutions-for-the-u-s-japanese-alliance/. The two countries have signed a Reciprocal Access Agreement as well.44“Japan, Australia Sign Defense Pact to Counter China’s Rise,” Nikkei Asia, January 6, 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/JapanAustralia-sign-defense-pact-to-counter-China-s-rise.

Meanwhile, US lawmakers have asked the Biden Administration to consider an enlargement of the “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing group (involving Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States) to include South Korea, Japan, India, and Germany.45US Congress, HR 4350–FY22 National Defense Authorization Bill, Subcommittee on Intelligence and Special Operations, https://docs.house.gov/ meetings/AS/AS00/20210901/114012/BILLS-117HR4350ih-ISOSubcommitteeMark.pdf.

It is also noteworthy that the US nuclear umbrella has been discreetly expanded in the past decade. Since the Nuclear Posture Review of 2010, nuclear extended deterrence explicitly covers not only allies but also “partners”—a formulation kept deliberately vague. This shift was confirmed by the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review.46US Department of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review Report, 2010, https://dod.defense.gov/News/Special-Reports/NPR/; and US Department of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, 2018, https://dod.defense.gov/News/SpecialReports/2018NuclearPostureReview.aspx. US nuclear weapons thus protect some fifty countries, or about one-quarter of the world’s total.

Support for US alliances around the world is at or near an all-time high. Opinion polls show that overwhelming national majorities support their country’s NATO membership.47NATO Public Diplomacy Division, “NATO Audience Research: Presummit Polling Results 2021,” June 11, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/ news_184687.htm. In the United States, polls by the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations showed that, for all of Trump’s negative rhetoric, solid majorities in 2020 continued to say alliances in Europe (68%) and East Asia (59%) mostly benefited the United States as well as its allies.48Dina Smeltz et al., Divided We Stand: Democrats and Republicans Diverge on US Foreign Policy, Results of the 2020 Council Survey of American Public Opinion and US Foreign Policy, Chicago Council on Foreign Relations, 2020, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/report_2020ccs_americadivided_0.pdf. In 2020, majorities of Americans wanted to either maintain or increase the US military presence in the Asia-Pacific region (78%), Africa (73%), Latin America (73%), Europe (71%), and the Middle East (68%).49Dina Smeltz et al., A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class: What Americans Think, Results of the 2020 Council Survey of American Public Opinion and US Foreign Policy, Chicago Council on Foreign Relations, 2021, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/ccs2021_fpmc_0.pdf. Americans were as willing as ever to send US troops to defend allies and partners, for instance in case of a North Korean invasion of South Korea (63%), in case of a Russian invasion of a NATO member (59%). And for the first time, a majority of Americans (52%) supported using US troops if China were to invade Taiwan.50Smeltz et al., A Foreign Policy for the Middle Class. In early 2022, according to two different polls, a surprising number of Americans and Europeans were ready to defend Ukraine.51Carl Bildt et al.,”Survey: Western Public Backs Stronger Support for Ukraine against Russia,” Atlantic Council, January 25, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/survey-western-public-backs-stronger-support-for-ukraine-against-russia/; and Ivan Krastev and Mark Leonard, “The Crisis of European Security: What Europeans Think About the War in Ukraine,” Policy Brief, European Council on Foreign Relations, February 9, 2022, https://ecfr.eu/publication/the-crisis-of-european-security-what-europeans-think-about-the-war-in-ukraine/. In February and March 2022, consensus in the NAC was easily achieved to bolster deterrence and defense of Central and Eastern European countries.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members signed a joint defense agreement in 2000, and since then have operationalized their “Peninsula Shield” common force. In Africa, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which includes a Protocol on Mutual Assistance and Defense (1981), has become a regional security actor through mediation and peacekeeping, notably through the establishment of ECOMOG (ECOWAS Monitoring Group). Members of its sister organizations, the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and the South African Development Community (SADC), signed their own Mutual Assistance Pact for the former (in 2000), and a Mutual Defense Pact for the latter (2003). In 2005, the 54 members of the African Union signed an all-African Nonaggression and Common Defense Pact.

The emergence of new alliances and security arrangements

In 1992, Russia forged the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) with Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan (three other ex-Soviet Republics later joined but then withdrew in 1999, when the treaty was renewed), a defense alliance despite its name. The CSTO created its own Collective Rapid Reaction Forces in 2009.52CSTO Joint Staff, “Collective Rapid Reaction Forces of the CSTO,” https://jscsto.odkb-csto.org/en/voennaya-sostavlyauschaya-odkb/ksorodkb.php. In 2010, the CTSO’s mutual defense provisions were significantly reinforced to include “other forms of armed attack that threaten the security, stability, territorial integrity and sovereignty of the parties.”53Collective Security Treaty, Collective Security Treaty Organization, https://en.odkb-csto.org/documents/documents/dogovor_o_kollektivnoy_ bezopasnosti/; Presidency of Russia, “Protocol on Amendments to the Collective Security Treaty Has Been Submitted to the State Duma for Ratification,” August 31, 2011, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/12507/print. That same year, Armenia and Russia signed a bilateral defense pact that included a security guarantee.54Breffni O’Rourke, “Russia, Armenia Sign Extended Defense Pact,” Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty, August 19, 2010, https://www.rferl.org/a/Russian_President_Medvedev_To_Visit_Armenia/2131915.html. The Russia-Belarus alliance has grown even stronger, with Minsk having amended its constitution in order to allow it to host nuclear weapons.55“Belarus Referendum Approves Proposal to Renounce Nonnuclear Status,” Reuters, February 27, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/launchpad-russias-assault-ukraine-belarus-holds-referendum-renounce-non-nuclear-2022-02-27/. In 2022, the CSTO intervened to help Kazakhstan, which claimed to face a “terrorist aggression,” suggesting that it may become a sort of Warsaw Pact-light organization.

After the 1991 Gulf War, France signed agreements that include defense clauses with Kuwait (1992), Qatar (1994, 1998), and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (1995, 2009). The UAE has become the most important ally of France in the Middle East: Paris committed itself to “participate in the defense of the security, the sovereignty, the territorial integrity, and the independence of the State of the United Arab Emirates,” and may engage its forces to “deter or repeal any aggression conducted by one or several States.”56République française, Décret n° 2012-495 du 16 avril 2012 portant publication de l’accord entre le Gouvernement de la République française et le Gouvernement des Emirats arabes unis relatif à la coopération en matière de défense, signé à Abou Dabi le 26 mai 2009, et de l’accord sous forme d’échange de lettres relatif à l’interprétation de l’accord de coopération en matière de défense, signées à Paris le 15 décembre 2010, Journal officiel de la République française, April 18, 2012, https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000025705803. The UK signed its own defense agreement with the UAE in 1996; the UK government’s comments in Parliament suggest that London is committed to deterring threats or preventing aggression against the Emirates, and, “in the event of such aggression taking place, to implementing the joint military plans which are judged appropriate for the defense of the UAE.”57UK Parliament, “Co-operation Accord (United Arab Emirates),” Hansard (official report of debates) 286, Commons: November 28, 1996, Written Answers, Defense, https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/1996-11-28/debates/becc7cbf-c160-4d16-95f4-b2fbf024a1ef/Co-OperationAccord(UnitedArabEmirates).

Not to be outmaneuvered, in 2006, Iran and Syria signed a mutual security pact that reportedly includes a defense clause (although a text has never been publicly released).58Bilal Y. Saab, “Syria and Iran Revive an Old Ghost with Defense Pact,” Brookings Institution, Op-Ed, July 4, 2006, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/ syria-and-iran-revive-an-old-ghost-with-defense-pact/; and United States Institute of Peace, “Syria’s Alliance with Iran,” USI Peace Briefing, May 2007, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/syria_iran.pdf. A few years later, in 2011, Turkey and Azerbaijan concluded a defense pact.59Shahin Abbasov, “Azerbaijan-Turkey Military Pact Signals Impatience With Minsk Talks: Analysts,” Eurasianet (news site), January 18, 2011, https://eurasianet.org/azerbaijan-turkey-military-pact-signals-impatience-with-minsk-talks-analysts. In 2020, Greece and the UAE signed a security agreement that reportedly contained a mutual defense clause.60Vassilis Nedos, “Greece, UAE Commit to Mutual Defense Assistance,” Ekathimerini, November 23, 2020, https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/259450/ greece-uae-commit-to-mutual-defense-assistance/.

In addition to formal agreements, a slew of defense cooperation groupings have also emerged in recent decades. These groupings have not replaced formal military alliances: their development comes on top of them.

The United States has considerably expanded the list of its major non-NATO allies, which number nineteen today, up from five in the late 1980s, plus Taiwan. Qatar has since joined and the total number (including Taiwan) is now 20.61US Department of State, “Major Non-NATO Ally Status,” Fact Sheet Washington is also stepping up its cooperation with non-NATO Northern European countries.62Aaron Mehta, “Finland, Sweden, and US Sign Trilateral Agreement, with Eye on Increased Exercises,” Defense News, May 9, 2018, https://www.defensenews.com/training-sim/2018/05/09/finland-sweden-and-us-sign-trilateral-agreement-with-eye-on-increased-exercises/. Separately, the five Nordic countries set up a common defense cooperation framework (NORDEFCO) in 2009. Three of them (Denmark, Norway, and Sweden) have agreed in 2021 to enhance operational cooperation.63Swedish Ministry of Defense, “The Defense Ministers of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden Sign Statement of Intent on Enhanced Operational Cooperation,” September 24, 2021, https://www.government.se/press-releases/2021/09/the-defence-ministers-of-denmark-norway-and-sweden-sign-a-trilateralstatement-of-intent-on-enhanced-operational-cooperation/. More recently, just before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the United Kingdom, Poland, and Ukraine are seeking to form a new security and defense partnership.64Matthias Williams and Gabriela Baczynska, “Britain, Poland, and Ukraine in Cooperation Talks over Russian Threat,” Reuters, February 1, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/britain-poland-ukraine-preparing-trilateral-security-pact-kyiv-says-2022-02-01/.

Regional cooperation is also on the rise in other parts of the world. In 2012, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey instituted a strategic partnership that includes a military dimension.65Zaur Shiriyev, Institutionalizing a Trilateral Strategic Partnership: Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Policy Paper, 2016, https://www.kas.de/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=cd257d1b-df92-5184-9ad4-2a5dd95c0886&groupId=252038. The defense ministers of Cyprus, Greece, and Israel have met annually since 2018. Following the 2020 Abraham Accords, the latter is now also seeking military ties with Gulf countries.66Dan Williams, “Israel Defence Chief Sees ‘Special Security Arrangement’ with Gulf States,” Reuters, March 2, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/usisrael-gulf-idUSKCN2AU1PW.

Nowhere is this expansion of informal security groupings clearer than in the Indo-Pacific region, where the United States has built a hub-and-spoke defense cooperation system. The Quad now has an explicit security (though not defense) dimension, something it did not have when this format was created in 2007. The first ever in-person summit of the leaders of the four countries was held in September 2021. There are now separate Australia-Japan-US and Korea-Japan-US defense forums.67US Department of Defense, “Australia-Japan-United States Defense Ministers’ Meeting Joint Statement,” July 7, 2020, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2266901/australia-japan-united-states-defense-ministers-meeting-joint-statement/; and Japanese Ministry of Defense, “JapanRepublic of Korea-United States Trilateral Ministers Meeting Joint Press Statement,” November 17, 2019, https://www.mod.go.jp/en/d_act/exc/area/docs/2019/20191117_j-kor.html. The new AUKUS trilateral security partnership set up in September 2021 brings together Canberra, London, and Washington. Even US-New Zealand defense cooperation is now being rejuvenated after decades of neglect.68United States | New Zealand Council, “Washington Declaration on Defense Cooperation,” US|NZ Council website, June 19, 2012, http://usnzcouncil.org/ us-nz-issues/washington-declaration/. The 1971 Five Power Defense Arrangements, which commit its members to consult in case of an armed attack against Malaysia or Singapore, are given a new life, due in particular to British and Australian interest.69Euan Graham, “The Five Power Defence Arrangements at 50: What’s Next?,” Analysis, International Institute for Strategic Studies (blog), December 10, 2020, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2020/12/five-power-defence-arrangements. The Indo-Pacific region has also featured the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM) since 2006, and the South Pacific Defense Ministers’ Meeting (SPDMM) involving Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, and Tonga since 2013.

Meanwhile, Russia and China started developing a tighter defense partnership after signing their Friendship and Cooperation Treaty in 2001, which was renewed in 2011 and 2021. The China-Russia relationship has turned into a near alliance, or at least a non-aggression pact à la the Treaty of Rapallo (1922). In fact, in recent years Moscow has started to use the words “alliance” or “allied” to qualify its relationship with Beijing.70Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, “Russia-China Strategic Alliance Gets a New Boost with Missile Early Warning System,” Diplomat, October 25, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/10/russia-china-strategic-alliance-gets-a-new-boost-with-missile-early-warning-system/. Decades-old, close military partnerships—quasi alliances—also continue to exist between China and Pakistan, as well as between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Generally speaking, defense cooperation agreements have proliferated since 1990, from less than one hundred to more than six hundred.71Brandon J. Kinne, “Defense Cooperation Agreements and the Emergence of a Global Security Network,” International Organization, August 15, 2018, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-organization/article/defense-cooperation-agreements-and-the-emergence-of-a-global-security-net work/76662383DB9CA3D26BE4FA883E5C95A2.

In sum, military ties are thickening globally. Alliances are modernizing and reinforcing themselves, with bilateral or multilateral military partnerships proliferating and expanding. Why is that so?

The endurance of existing military alliances can be partly explained by mere inertia, vested interests, and sunk costs.72Stephen M. Walt, “Why Alliances Endure or Collapse,” Survival 39, no. 1 (1997): 156-179, doi: 10.1080/00396339708442901. Yet, there is more to it than that. Since 1815, offensive alliances have become a rarity. Modern alliances are defensive in nature and, as a result, are more resilient and durable than aggression-oriented pacts of the distant past. Moreover, except in rare cases, they are generic as opposed to threat specific (i.e., designed to face one single, explicitly identified threat73This is the case for the US commitment to the South-East Asia Treaty (see below).). They apply to any aggression.74Mira Rapp-Hooper, “Absolute Alliances: Extended Deterrence in International Politics” (doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, 2015), Columbia University Academic Commons (website), https://doi.org/10.7916/D85Q4TWX.

This has rendered them capable of confronting the reemergence (Russia) or growth (North Korea, China) of perceived threats, or to be the vehicle for dealing with new ones such as terrorism. The ANZUS treaty was initially set up to counter a possible resurgence of Japanese militarism. The European mutual defense commitment enshrined in the Lisbon Treaty is the distant successor to the Brussels Treaty of 1948, which itself was an enlargement of the Treaty of Dunkirk, a defense pact signed the previous year by London and Paris to protect against Germany.

All this helps explain why alliances endure today. Since 1945, alliances have lasted fourteen years on average, compared with eight years before then.75Breet Ashley Leeds et al., “Reevaluating Alliance Reliability: Specific Threats, Specific Promises,” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 44, no. 4 (2000), https://www.jstor.org/stable/174649. The expansion of the sphere of security competition at sea (with a growing number of open disputes), as well as in cyberspace and outer space, has led allies to confirm or expand their security guarantees.

The growth of the Western system of military alliances and partnerships is partly a consequence of the radicalization of Russian and Chinese policies. To use political science jargon, there is more balancing going on vis-à-vis Moscow and Beijing, and more bandwagoning with the United States. Russia and China have few military allies (only one formal ally for Beijing: North Korea).

There is more to it than that, though. The US system of alliances is “unique in human history.”76Kathleen J. McInnis, “The Competitive Advantages and Risks of Alliances,” Heritage Foundation, October 30, 2019, https://www.heritage.org/militarystrength-essays/2020-essays/the-competitive-advantages-and-risks-alliances. It is institutionalized like no other. A few years ago, a scholar calculated that US alliances covered some 25 percent of the world’s population and 75 percent of its gross domestic product.77Michael Beckley, “The Myth of Entangling Alliances: Reassessing the Security Risks of US Pacts,” International Security 39, no. 4 (Spring 2015), https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/IS3904_pp007-048.pdf. NATO is not only the biggest formal alliance in membership in the world but also one of the only two with a permanent military command (the other being the ROK/US Combined Forces Korea). NATO has also proven flexible enough to lead major operations with nonmembers, such as in Kosovo, Afghanistan, or Libya. Unlike ad hoc coalitions of the willing, NATO allows for collective decision-making, tested procedures, interoperability, and the use of common assets.

The United States stands out as a security guarantor due to the combination of its enjoyable location, its democratic nature, and its unparalleled power. US-led formal alliances are unique in that they involve both interests and ideals.78Bruno Tertrais, “The Changing Nature of Military Alliances,” The Washington Quarterly 27, no. 2 (Spring 2004), https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/twq04springtertrais.pdf. Today, the US administration is expanding and consolidating these links seeking to “build a latticework of alliances and partnerships globally that are fit for purpose for the twenty-first century.”79“A Conversation With Jake Sullivan,” Council on Foreign Relations, December 17, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/event/conversation-jake-sullivan. North Korean, Iranian and, to some extent, Turkish foreign policies have also contributed to various states seeking new defense partnerships for mutual protection.

Of course, this proliferation of defense accords would not have happened if security guarantors—Washington in particular—did not have direct interests at play. The protection of a weaker power remains a vehicle for political influence, commercial benefits (notably arms sales),80A. Trevor Thrall et al., “Power, Profit or Prudence? US Arms Sales Since 9/11,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 14, no. 2 (Summer 2020), https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/SSQ/documents/Volume-14_Issue-2/Thrall.pdf. military access (bases), capabilities, and legitimacy for common operations.81See Olivier Schmitt, Allies That Count: Junior Partners in Coalition Warfare (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2018). For a good “balance sheet” of US alliances, see Hal Brands and Peter Feaver, “What Are America’s Alliances Good For?,” Parameters 47, no. 2 (2017), https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2928&context=parameters. Leaving aside the specific case of the Warsaw Pact, which was an instrument to control its members, these interests are never one-sided, and allies clearly see an upside to continued cooperation. Allies return the favor when they participate in operations led by their protector, for instance in the Middle East and Central Asia for the United States, or in the Sahel for France. They show goodwill by siding with their protectors on contested issues. This is what political scientist Glenn Snyder called the “halo effect” of alliances.82Glenn Herald Snyder, Alliance Politics (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1997), 8.

Reassurance is also instrumental in reducing the risk of a renationalization of defense policies. This was an acute concern in 1945 (when NATO was also about “keeping the Germans down”) and immediately after the Cold War. It also helps reduce the risk of nuclear proliferation, a long-standing US and global concern: extended nuclear deterrence is widely considered the best way to discourage an ally from embarking on developing a nuclear weapons program of their own. Alliances also have a pacifying effect: they damp the risk of open conflict among members. This, in turn, facilitates economic cooperation and growth—the best examples being the recovery of Europe, Japan, and South Korea after 1945.

US attitudes have also led to consolidation of military ties between its own allies and friends, either to diversify security portfolios or to hedge against US retrenchment—“internal hedging,” given that all the actors belong to the same US-led alliance system. This is the case for Gulf countries, for instance, or for the aforementioned Greece-France security partnership.

Finally, the reinforcement of defense arrangements may reflect the post-1990 maturation of regional organizations, as was the case in Europe and to a lesser extent in Africa.

Is the expansion stabilizing or destabilizing?

There are well-known objections to the multiplication of alliances, including free-riding (hence the classic burden-sharing debate within NATO, for instance) and overextension (the risk of an alliance being able to credibly uphold all its commitments). Two timelier questions stand out at this particular moment in world history: is this thickening web of alliances good or bad for global stability, and does it increase or decrease the risk of war? While definitive judgments are impossible to make, arguments claiming that alliances are good for stability are convincing.

Deterrence is an improbable proposition, but it does seem to work. Russia and China have never openly attacked territories clearly covered by Western security guarantees. By contrast, they have invaded or encroached upon nonprotected countries and disputed territories.

Alliances also contribute to keeping the peace internally. The protector power can play a mediating role between allies, as the United States sometimes does between Greece and Turkey, or between Japan and South Korea.

The defensive nature of modern alliances provides stability and predictability in the international system.83To be sure, Russia claims that NATO’s role in the ex-Yugoslavia or in Libya is the proof of its “offensive” nature, but such compellence (i.e., coercive) operations were designed to protect civilians, not, say, to invade a country. Such alliances provide stability and predictability in the international system. There is solid academic evidence that such alliances do reduce the risk of war.84Jesse C. Johnson and Brett Ashley Leeds, “Defense Pacts: A Prescription for Peace?,” Foreign Policy Analysis 7, no. 1 (2011), https://academic.oup.com/fpa/article-abstract/7/1/45/1795309; and Thorin M. Wright and Toby J. Rider, “Disputed Territory, Defensive Alliances and Conflict Initiation,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 31, no. 2 (2014), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0738894213503440. They are also less likely in themselves to produce a pushback from other countries (the “security dilemma”), especially when they adopt unilateral confidence-building measures aimed at reassuring a potential adversary that they have no aggressive designs against it. Moreover, defensive alliances often operate by consensus.85This is the case for two of the most important ones: NATO and the CSTO. This is also true for some bilateral defense commitments such as the Franco-Greek one of 2021, which includes the condition that both parties must “jointly” find that an armed aggression has taken place. For example, it is not certain how NATO, with its thirty members, could obtain consensus to a policy of aggression.86Absent consensus, nothing would prevent the collective exercise of self-defense—especially since NATO’s supreme commander in Europe is also commander of US Forces in Europe—however, collective NATO-only assets would not be accessible. Almost all defense commitments have significant caveats that are stabilizing.87The Article 5 language was a compromise between the language of the Rio and Brussels treaties. See Bruno Tertrais, “Article 5 of the Washington Treaty: Its Origins, Meaning and Future,” Research Paper no. 130, NATO Defense College, April 2016, https://www.ndc.nato.int/news/news.php?icode=934. Most of the time, they do not compel allies to use military force, and where applicable they mention national restrictions such as “the constitutional provisions and processes” (US-Japan) or “the specific character of the security and defense policy of certain member States” (Treaty on European Union, or TEU88This is known as the “Irish clause” and is designed to accommodate the specific policies of Austria, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Malta, and Sweden. See Clara Sophie Cramer and Ulrike Franke, eds., “Ambiguous Alliance: Neutrality, Opt-Outs, and European Defence,” Essay Collection, European Council on Foreign Relations, June 2021, https://ecfr.eu/publication/ambiguous-alliance-neutrality-opt-outs-and-european-defence/.).

These alliances also apply only to a defined area. The NATO treaty, which defines at length its scope of application, concerns only “Europe and North America.” This includes Alaska but not Hawaii and US territories in the Pacific.89The North Atlantic Treaty, April 4, 1949, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_17120.htm; see Tertrais, “Article 5 of the Washington Treaty.” The US-Japan treaty covers “the territories under the administration of Japan.”90The treaty of mutual cooperation and security between Japan and the United States, January 19, 1960, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/n-america/us/q&a/ ref/1.html. The US-South Korea one is drafted along the same lines: “an armed attack in the Pacific area on either of the Parties in territories now under their respective administrative control, or hereafter recognized by one of the Parties as lawfully brought under the administrative control of the other.”91Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Korea, October 1, 1953, https://www.usfk.mil/Portals/105/Documents/SOFA/H_ Mutual%20Defense%20Treaty_1953.pdf. The US-Philippines treaty’s scope is “the metropolitan territory of either of the Parties, or on the island territories under its jurisdiction in the Pacific or on its armed forces, public vessels, or aircraft in the Pacific.”92Mutual Defense Treaty between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines, August 30, 1951, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/phil001.asp.

Almost all of these alliances are vague enough or contain sufficient ambiguity to avoid the protected party believing that its security guarantor would automatically use force to defend it. The most significant caveat of the majority of treaty-based commitments is the very notion of “armed attack,” the casus fœderis of defense alliances. In international law, “aggression” refers to Article 39 of the UN Charter (“threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression”). UN General Assembly Resolution 3314 (1974) defines it as “the use of armed force by a State against the sovereignty, territorial integrity, or political independence of another State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Charter of the United Nations.”93Elizabeth Wilmhurst, “Definition of Aggression,” General Assembly Resolution 3314 (XXIX) of December 14, 1974, Audiovisual Library of International Law, https://legal.un.org/avl/ha/da/da.html. An “armed attack”— which authorizes self-defense—refers to Article 51 of the Charter and is one step higher. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) considers that its characterization requires “a relatively large scale . . . a sufficient gravity, and . . . a substantial effect.”94Albrecht Randelzhofer and Georg Nolte, “Article 51,” in The Charter of the United Nations: A Commentary, eds. Bruno Simma et al., Third Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 1409.

Still, drawing red lines—the essence of security guarantees—is a form of art.95On the notion of red lines, see Bruno Tertrais, “The Diplomacy of ‘Red Lines,’” Recherches & Documents, no. 2 (2016), Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/recherches-et-documents/2016/201602.pdf. The line should be clear enough to deter, but not to the point of ensuring the adversary he will not suffer from consequences if he acts below the line. It must also leave enough room of maneuver to the protector. And today more than ever, red lines are drawn over gray areas.

What exactly does “armed attack” mean in a century of hybrid threats, from election interference and political manipulation to cyberattacks, frozen conflicts, “little green men” in Europe, and land reclamation in Asia?96In international law, “armed attack” authorizes self-defense and differs from mere “aggression.” The French language obfuscates the difference between the two by using the expression “agression armée” for “armed attack.” In its landmark 1986 Nicaragua decision, the ICJ stated that armed attack may include “the sending or on behalf of a State of armed bands, groups, irregular or mercenaries” provided that the adverse State has “effective” control over them.97Karl Zemanek, “Armed Attack,” Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, October 2013), https://opil.ouplaw.com/view/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e241. But it remains by no means certain that alliance members would easily agree on triggering security guarantees for political interference or nonovert attack of militias or nonuniformed forces, in Europe or in Asia (the “little blue men” of civilian Chinese boats). The same problem exists with major cyberattacks, which could qualify as armed attacks warranting self-defense only if attribution could be ascertained—something which may be extremely difficult.

For militia as well as cyberattacks, international law provides the useful concept of cumulative effects. This was made clear by the ICJ’s rulings: an accumulation of minor events could be tantamount to an armed attack.98Zemanek, “Armed Attack.” (NATO adopted it in 2021 for cyberattacks and there is thus no reason why it could not use it also for militia attacks.99Brussels Summit Communiqué Issued by the Heads of State and Government Participating in the North Atlantic Council in Brussels.”) The problem with this notion, which is also applicable to any escalation scenario starting with a minor incident, is that there is no obvious threshold for declaring that security guarantees are at play. This is a classic problem akin to salami slicing or the “boiling frog” theory: the water is so slowly heated that the frog never realizes when it is about to die.

Another uncertainty relates to the exact definition of protected territories, the centerpiece of security guarantees. To be sure, this has never been a simple thing: many borders are undefined or contested. Yet this is increasingly a problem at sea. Since the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Seas entered into force in 1994, many states have made irreconcilable claims regarding their territorial waters as well as economic exclusion zones (EEZs, which are not part of national territories but where national forces are often present). China specifically has had an active policy of land reclamation and occupation in the South China Sea aimed at creating “facts on the water” to alter the legal status of rocks, islets, and reefs it controls.

Another problematic example is the European Union. Where exactly does Article 42.7 of TEU apply? This simple question has no clear answer given the many special statuses of European territories. As one legal commentator put it, “EU law applies very differently to Campione d’Italia, the Holy Mount Athos, the municipality of Budapest, the double kingdom of Wallis-et-Futuna within the French Republic, Martinique, or the Island of Bonaire.”100Dimitry Kochenov, “The Application of EU Law in the EU’s Overseas Regions, Countries, and Territories After the Entry into Force of the Treaty of Lisbon,” Michigan State International Law Review 20, no. 3 (2012): 674, https://www.montesquieu-instituut.nl/9353262/d/Kochenov%20EU%20Law%20in%20 the%20Overseas.pdf.

Finally, there are some lingering uncertainties inherited from the Cold War. The US commitment to its South-East Asia Treaty allies only applies to “Communist aggression.”101South East Asia Collective Defense Treaty (with Protocol) of September 8, 1954, United Nations (website), https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/ volume%20209/volume-209-i-2819-english.pdf. Would contemporary China appear qualified as such by all signatories?

All this suggests that allies do not get embroiled by mere virtue of a text or declaration: going to war would remain a political decision.

Concerns about entrapment

Protected parties may fear abandonment, but security guarantors fear “entrapment.”102The word “entanglement” is often used, but alliances by nature “entangle” the interests of their members. Entrapment is “a form of undesirable entanglement.” See Tongfi Kim, “Why Alliances Entangle but Seldom Entrap States,” Security Studies 20, no. 3 (2011): 350-377, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09636412.2011.599201. This refers to situations where allies are dragged into war due to alliance commitments. This may be due to the emboldening of protected allies or fear for their own reputation.103Dominic Tierney, “Does Chain-Ganging Cause the Outbreak of War?,” International Studies Quarterly 55 (2011), https://academic.oup.com/isq/ article/55/2/285/1791143?login=true.

In some circumstances alliances may embolden member states to initiate disputes against nonmember states and be more likely to aggravate dispute initiation against member states.104Choong-Nam Kang, “Capability Revisited: Ally’s Capability and Dispute Initiation,” Conflict Management and Peace Science, 34, no. 5 (2017), https://www.jstor.org/stable/26271480. (Recall that President Trump’s disparaging comments about the “tiny” and “aggressive” country of Montenegro were precisely meant to signal the fear that an ally could drag the United States into “World War III.”105Macias and Higgins, “Trump Says Defending Tiny NATO Ally Montenegro.”) In particular, “revisionist countries holding unconditional deterrent agreements are more likely to initiate conflict than if they had not been given an alliance or had been given a conditional deterrent alliance instead.”106Brett V. Benson et al., “Ally Provocateur: Why Allies Do Not Always Behave,” Journal of Peace Research 30 (2013), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0022343312454445.

However, there is little evidence that contemporary allies have shown aggressiveness in their neighborhood without fear of retaliation because they felt protected.107A legitimate question mark could exist for Turkish behavior in recent years, but given the tensions between Ankara and its allies—notably the United States—it is unlikely that It played a role. True, weaker parties can—sometimes in good faith—mistakenly convey to their publics that contested territories would be protected. The public debates surrounding the Russia-Armenia defense accord of 2010 (about Nagorno-Karabakh), or the France-Greece strategic partnership of 2021 (about the Greek EEZ), are cases in point.108See Breffni O’Rourke, “Russia, Armenia Sign Extended Defense Pact,” Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty, August 19, 2010, https://www.rferl.org/a/Russian_President_Medvedev_To_Visit_Armenia/2131915.html; and Bruno Tertrais, “Reassurance and Deterrence in the Mediterranean: The Franco-Greek Defense Deal,” Institut Montaigne, November 17, 2021, https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/blog/reassurance-and-deterrence-mediterranean-francogreek-defense-deal. In both cases, however, clarifications were given by the protector. As Lanoszka explains, entrapment is “a self-denying prophecy.”109Lanoszka, Military Alliances, 51.

A second issue is entrapment through reputation concerns, which are often raised as a reason to intervene in defense of an ally or a partner. A classic case of this for the United States was Vietnam. Yet this fear too seems overblown.

Reputation does matter when explaining choices made by US administrations.110Frank P. Harvey and John Mitton, Fighting for Credibility. US Reputation and International Politics (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017); and Alex Weisiger and Keren Yarhi-Milo, “Revisiting Reputation: How Past Actions Matter in International Politics,” International Organization 69, no. 2 (2015), https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-organization/article/revisiting-reputation-how-past-actions-matter-in-international-politics/8BF54EA849FC4925FDC4C43FB9A810C4. Yet an analysis of US commitments by political scientist Michael Beckley supports the idea that overall, Washington maintained its freedom of action when deciding whether or not to intervene: it found only five examples of ostensible US entanglement since 1945 (the Taiwan Strait crises of 1954 and 1995, the Vietnam War, and interventions in Bosnia and Kosovo in the 1990s).111Michael Beckley, “The Myth of Entangling Alliances: Reassessing the Security Risks of US Pacts,” International Security 39, no. 4 (2015), https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/files/IS3904_pp007-048.pdf. Even in such cases, the United States had many interests at stakes, not just those related with reputation. By contrast, Washington did not support the French in Dien Bien Phu or the British in the Falklands. Moreover, the US actually undermined both in the Suez crisis.

Allies in fact often play the role of a brake on escalation. To be sure, faced with the prospect of their protector getting involved in a distant contingency, they could welcome the effective exercise of security guarantees since it would validate in their eyes the one they benefit from. Yet the same allies could also serve as a restraining factor, fearing that their own regional interests would then be less protected (a classic case being Europeans concerned about Vietnam).112Allies can also play a restraining role on enlargement, as demonstrated by the French and German refusals to offer a NATO Membership Action Plan to Georgia and Ukraine in 2008 and more recently in 2022 with Turkey’s opposition to Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO. As Beckley explains, “in most conflicts, only a few allies were directly threatened and demanded US intervention. …Most allies…urged restraint because they worried their security would suffer if the [United States] drained its strength in a peripheral region or escalated a faraway conflict into a global war.”113Michael Beckley as quoted by Adam Taylor, “Map: The US is Bound by Treaty to Defend a Quarter of Humanity,” Washington Post, May 30, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/05/30/map-the-u-s-is-bound-by-treaties-to-defend-a-quarter-of-humanity/.

Recent events show that NATO has been cautious in invoking Article 5: it was not done in 2007 when massive distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks of Russian origin affected Estonia, or when a Turkish aircraft was downed by Syria over international waters in 2012. Likewise, Seoul and Washington did not overreact when North Korea attacked a South Korean ship and shelled islands in 2010; the CSTO did not move when a missile fell on Armenian territory in 2020; and Iranian attacks on Saudi territory over the past decade elicited fairly measured US reactions. If anything, the United States occasionally appears hesitant in upholding its own red lines, to the point that some have wondered whether its nonintervention in Syria in 2013 might have encouraged Russian and Chinese aggressiveness.114See Jeffrey Lewis and Bruno Tertrais, “Beyond The Red Line: The United States, France, and Chemical Weapons in the Syrian War, 2013-2018,” Recherches & Documents no. 6 (2018), Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, https://www.frstrategie.org/web/documents/publications/recherches-etdocuments/2018/201806.pdf.

In fact, modern defense commitments are vaguer than they were in the past in terms of the anticipated allied response.115As an example, the Dual Alliance of 1879 committed Austria-Hungary and Germany to come down on Russia with “the whole war strength of their empires.” See “The Dual Alliance Between Austria-Hungary and Germany – October 7, 1879,” The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy, Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library (website), accessed May 30, 2022. This contributes to the freedom of action of guarantors.

For all these reasons, implementing a security guarantee would not be automatic—and in many cases, it would be a matter of political, more than legal, judgment. Moreover, there is of course the possibility that a guarantee breaks down even though the circumstances for which it was designed—i.e., a clear-cut armed attack—are present. Defensive alliances are not always upheld: a recent academic analysis found that they are honored only 41 percent of the time.116Molly Berkemeier and Matthew Fuhrmann, “Reassessing the Fulfillment of Alliance Commitments in War,” Research & Politics 5, no. 2 (April-June 2018), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2053168018779697. (Then again, those including nuclear powers are rarely tested either.) What if, for instance, a US president refused to defend a smaller NATO member against regional aggression? Ultimately, security guarantees may work as reassurance, but fail not only at deterrence but also at collective defense.

The reference to a possible 1914-like sequence of events— in reference to how the European alliance system is said to have facilitated the march to general war by “chain-ganging”—thus seems off.

Two additional arguments will make this clearer. First, the traditional narrative of World War I as a case of unfortunate “chain-ganging” is now challenged by historians. In 1914, Dominic Tierney argues, “the war began, not as a result of chain-ganging, but because of coordinated aggression by Germany and Austria-Hungary. The latest historical research on the origins of World War I is inconsistent with the chain-ganging hypothesis.”117Tierney, “Does Chain-Ganging Cause,” 299.

Second, the early twenty-first century network of alliances and partnerships is not the equivalent to those of the twentieth century. The United States has five dozen allies, and Russia has five. China and India, the two most-populous countries in the world, have been unwilling to sign new defense commitments. Despite the closeness between Pakistan and China, Islamabad insists that it does not want to be part of any “bloc.”118Ayaz Gul, “Pakistan’s PM Urges US, China to Reduce Tensions,” Voice of America, December 9, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/pakistan-s-pm-urgesus-china-to-reduce-tensions/6346614.html. In fact, Beijing has always claimed that the US network of global alliances is a cover for hegemony.119“China Believes That America Is Forging Alliances to Stop Its Rise,” Economist, September 25, 2021, https://www.economist.com/china/2021/09/25/ china-believes-that-america-is-forging-alliances-to-stop-its-rise. The multiplication of informal defense arrangements and partnerships is more likely to dampen the risk of escalation than to increase it: it creates uncertainties in the adversary’s mind about how a nonformally-allied country (say Sweden or India) would react to an attack against an ally, and vice versa. There is little evidence of a true “clash of alliances in the Pacific” that would pit what an author calls a “JAUKUS” (Japan and AUKUS countries) bloc against a “RUCNDPRK” (Russia, China and North Korea) one.120Artyom Lukin, “‘JAUKUS’ and the Emerging Clash of Alliances in the Pacific,” PacNet Commentary no. 59, Pacific Forum International, December 22, 2021, https://mailchi.mp/pacforum/pacnet-59-jaukus-and-the-emerging-clash-of-alliances-in-the-pacific-1172630?e=5ea77c93b0.

Finally, it should be noted that the military culture of the early twentieth century was heavily geared toward what was called the “cult of the offensive.” We live in a different time.

Wartime: How would the system work?

Still, the unprecedented contemporary web of alliances leaves many questions open as to how it would operate in wartime. There are several kinds of major scenarios that warrant discussion. How would Western security guarantees operate and interact given different geographical contexts (Europe or Asia) and scopes (initially involving external actors or only local ones).

Clear-cut cases of aggression triggering security guarantees include the following scenarios: a Russian attack against Poland, the Baltic states or Turkey; a North Korean offensive against South Korea; a Chinese operation against Taiwan; a China-Japan fight over the Senkaku islands; a North Korean strike against Japan; a China-Philippines war in the South China Sea; and an Iranian attack against a Gulf State or Israel. In all of the above cases, most Western countries would almost certainly support the United States as well as their friends and allies across the globe.

In case of a conflict in East Asia, the probability that allies would be directly pulled into combat operations is low (except perhaps for the case of South Korea, due to the aforementioned 1953 commitments by sixteen countries to defend the peace on the peninsula). Some European countries may end up involved in maritime security operations in the South China Sea, for instance, to secure vital arteries of global trade. France and the United Kingdom, by virtue of their permanent membership of the UN Security Council and their roles in the Indo-Pacific region, would have specific reasons to participate in such scenarios. Such conflicts could, however, escalate quickly. China or North Korea could warn US allies to “stay out” by reminding them of the vulnerability of their countries to cyberattacks and missile strikes—which, in turn, would force Paris or London to counter Bejing’s threats through deterrence. A missile threat against US territory in North America would in turn compel NATO allies to express their solidarity with Washington and get involved.

Meanwhile, NATO would have to guard against opportunism by Russia. In case of a near-simultaneous Russian attack in Europe, the US Army could still play a major role—it would not be heavily involved in most Asian contingencies—but “the [US Navy] and [Air Force] would largely play support and coordinative roles.”121Robert Farley, “Can the US Military Still Fight a Two Front War and Win?,” National Interest, January 22, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/reboot/canus-military-still-fight-two-front-war-and-win-176799. In other words, the Europeans could not hide behind the Americans to blunt and counter a Russian attack and backfilling would be the order of the day.

Similar questions would be raised in case the initial scenario is a European one, but the parallel is limited. In relative terms, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, or Australia would have less immediate interests in Eastern Europe than France, Germany, or the United Kingdom would in East Asia. It is harder to imagine that Russia could threaten Asian allies of the United States for their support of Europe than in the China or North Korean case. In any case, here, too, the Europeans should expect to carry a heavier part of the burden than would have been the case during the Cold War. It is not widely known that during the Obama administration, for the first time ever, “the United States formally clarified to allies… that should a crisis arise in the NATO Treaty Area, a significant portion of its capabilities and capacity might be committed to Combatant Commands in other regions and hence not available to NATO.”122Robert G. Bell, “NATO Nuclear Burden-Sharing Post-Crimea: What Constitutes “Free-Riding?” (doctoral dissertation, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, June 2021), 61.

The Trump presidency also highlighted the possibility of a nightmare scenario for Europeans: what if the United States refused to fulfill its promise to defend them in case of Russian aggression? As suggested above, failure to obtain consensus in the NAC would not paralyze action: collective self-defense would still be possible (though without NATO common assets). Recall also that Article 42.7 of TEU binds Europeans—actually in a stronger way than Article 5 of the Washington Treaty—and that it thus plays the role of supplementary insurance.123The Washington Treaty’s Article 5 reads: “will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith . . . such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force.” The TEU’s Article 42.7 reads: “shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power.” Note also that the former refers to “armed attack” and the latter to “armed aggression.” Whether this is a production of the French translation or a deliberate broadening is debated. See J. F. R. Boddens Hosang and P. A. L. Ducheine, “Implementing Article 42.7 of the Treaty on European Union: Legal Foundations for Mutual Defence in the Face of Modern Threats,” Amsterdam Law School Research Paper No. 2020-71, Amsterdam Center for International Law No. 2020-35, December 2020, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3748392.

Thus, if simple models of a division of labor between Europeans and Americans in case of major war accurately reflect the complex realities of how such crises would unfold, Europeans should expect to take up more defense responsibilities for the defense of the continent, whatever the scenario.