Permanent deterrence: Enhancements to the US military presence in North Central Europe

North Central Europe has become the central point of confrontation between the West and a revisionist Russia. Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia is determined to roll back the post-Cold War settlement and undermine the rules-based order that has kept Europe secure since the end of World War II. Moscow’s invasion and continued occupation of Georgian and Ukrainian territories, its military build-up in Russia’s Western Military District and Kaliningrad, and its “hybrid” warfare against Western societies have heightened instability in the region have made collective defense and deterrence an urgent mission for the United States and NATO.

The United States and NATO have taken significant steps since 2014 to enhance their force posture and respond to provocative Russian behavior. Despite these efforts, the allies in North Central Europe face a formidable and evolving adversary, and it is unlikely that Russian efforts to threaten and intimidate these nations will end in the near term. Now, ahead of NATO’s seventieth anniversary there is more that can be done to enhance the Alliance’s deterrence posture in the region. Against this backdrop, the government of Poland submitted a proposal earlier this year offering $2 billion to support a permanent US base in the country. While negotiations are ongoing, the issue is fundamentally about what the United States and NATO need to do to defend all of Europe.

To provide an independent perspective, the Atlantic Council established a task force to assess the broader political and military implications of an enhanced US posture in North Central Europe. The report’s recommendations, guided by several key principles, are a result of the task force members’ agreement that enhancements to the US presence in the region could, and should, be undertaken to bolster deterrence and reinforce Alliance cohesion. The release of this full-length report follows a preview of the report released in December.

Table of contents

Atlantic Council Task Force on US force posture in North Central Europe

Current and anticipated security environment

Political, diplomatic, and military considerations

Principles for enhanced deterrence

Recommended enhancements to US force posture in North Central Europe

Atlantic Council Task Force on US force posture in North Central Europe

In September 2018, the Atlantic Council established a task force on US Force Posture in Europe to assess the adequacy of current US deployments, with a focus on North Central Europe. The task force was co-chaired by General Philip M. Breedlove, USAF (Ret.), former NATO supreme allied commander Europe (SACEUR) and former commander of US European Command (EUCOM), and Ambassador Alexander R. Vershbow (Ret.), former NATO deputy secretary general.

This report is a product of the task force’s assessment of the security situation in North Central Europe, including the military balance and the threats to military stability and peace, today and in the foreseeable future. The report also recommends actions the United States should take to enhance deterrence and defense against aggression toward US allies in that region.

This set of force-posture recommendations has been approved by the two co-chairs as the appropriate response to the current and projected military and geopolitical situation in North Central Europe. All recommendations have been endorsed by the other members of the task force as steps that would strengthen the US posture in the region, in order to bolster NATO deterrence and political cohesion.

Executive summary

North Central Europe has become a central point of confrontation between the West and a revisionist Russia. Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia is determined to roll back the post-Cold War settlement, undermine the sovereignty of former Soviet states, and overturn the US-led, rules-based order that has kept Western Europe secure since the end of World War II and enlarged to countries of Central and Eastern Europe after 1989. Moscow’s invasion and continued occupation of Georgian and Ukrainian territories, its military build-up in Russia’s Western Military District and Kaliningrad, its intervention in Syria, and its “hybrid” warfare against Western societies have heightened instability in the region and made collective defense and deterrence an urgent mission for the United States and NATO.

The United States and NATO have taken significant steps since 2014 to enhance their force posture in Europe and respond to provocative Russian behavior. Despite these efforts, the allies in North Central Europe face a formidable and evolving adversary, and it is unlikely that Russian efforts to threaten and intimidate these nations will end in the near term. Now, ahead of NATO’s seventieth anniversary, more can, and should, be done to enhance the Alliance’s deterrence posture in the region.

Against this backdrop, the Republic of Poland submitted to the United States in April 2018 a proposal to host, on a permanent basis, a US military division on Polish territory, and offered $2 billion to finance infrastructure for that deployment. While the Polish offer is being weighed inside the United States, the issue is broader than just enhancing the US presence in Poland; it is fundamentally about what the United States and NATO need to do to defend all of Europe. Any decision about an enhanced US presence in Poland would have serious implications for the region and for the Alliance as a whole. The ongoing negotiations and discussions on this matter, within the US government and in Poland, could significantly benefit from an independent perspective outside the US government that considers these issues in the context of a broader, long-term transatlantic approach toward Russia.

To that end, the Atlantic Council established a task force, led by General Philip Breedlove and Ambassador Alexander Vershbow, to assess the broader political and military implications of an enhanced US posture and presence in North Central Europe and provide recommendations for the way forward. This report and its recommendations are products of the task force’s study, consultations, and deliberations on the current US military force posture in North Central Europe. Overall, the members of the task force agree that significant enhancements to the existing US presence could, and should, be undertaken to bolster deterrence and reinforce Alliance cohesion. The task force members also believe this can be done while maintaining the framework of deterrence by rapid reinforcement reaffirmed by allied leaders at the 2018 NATO Brussels summit, and while avoiding a divisive debate on the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act.

The task force’s recommendations are focused on negating the threat of a fait accompli that could be achieved by a limited Russian land grab in the Baltic States. Although NATO’s aggregate conventional capabilities surpass those of Russia, Russia maintains a conventional overmatch on its border with NATO allies. The recommendations in this report would reduce NATO’s time-distance gap, improving the ability of allied forces to defend the Baltic region in the initial period of a conflict, while facilitating rapid reinforcement into the area. These enhancements to US presence in North Central Europe are designed to create an untenable risk for Russia in any military operation against NATO.

The task force has outlined several key principles that should guide US decisions regarding the United States’ force posture in Europe, asserting that any deployment should:

- enhance the United States’ and NATO’s deterrent posture for the broader region—not just for the nation hosting the US deployment— including strengthening readiness and capacity for reinforcement;

- reinforce NATO cohesion;

- promote stability with respect to Russian military deployments to avoid an action-reaction cycle;

- be consistent with the US National Defense Strategy and its concept of dynamic force employment;1Dynamic force employment is an effort to prepare the US military to transition from a focus on fighting terrorist groups to a possible great-power conflict, with about the same force size. It calls for greater agility, more lethality, less operational predictability, higher readiness, irregular deployments, and maximum surge capacity. See Department of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2018), 7, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf.

- include increased naval and air deployments in the region, alongside additional ground forces and enablers;

- promote training and operational readiness of US deployed forces and interoperability with host-nation and other allied forces;

- ensure maximum operational flexibility to employ US deployed forces to other regions of the Alliance and globally;

- expand opportunities for allied burden sharing, including multilateral deployments in the region and beyond; and

- ensure adequate host-nation support for US deployments.

In addition, US and NATO decisions should be made in a way that strengthens the foundation of shared values and interests on which the Alliance rests.

Within these parameters, the task force members propose a carefully calibrated package of permanent and rotational deployments in Poland and the wider region. This would largely build on the significant US capabilities already deployed in Poland, and should be complemented by capabilities from other NATO allies. Ultimately, the recommended package would make certain elements of the current US deployment in Poland permanent, strengthen other elements of that deployment by reinforcing the brigade combat team (BCT) deployed there with various enablers, assign an- other BCT on a permanent or rotational basis to Germany, establish a more frequent rotational US presence in the Baltic States, and increase the US naval presence in Europe. The task force members are confident this can all be done while maintaining NATO solidarity and enhancing burden sharing among allies. The task force strongly recommends that the United States and the rest of the Alliance move forward on this basis.

These recommendations, laid out in detail would maintain a continuous US rotational military presence at permanent installations in North Central Europe by:

- upgrading and making permanent several headquarters units, to provide continuity for command elements;

- making rotational units in Poland and the Baltic States more predictable, continuous, and enduring;

- deploying more enablers to the region;

- strengthening other US forces in Europe for training and rapid reinforcement to the northeastern region, and making Poland a staging area for forward operations; and

- ensuring and accelerating European Defense Initiative funding, and focusing Polish financial contributions on training facilities.

Introduction

North Central Europe has become a central point of confrontation between the West and a revisionist Russia. Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia is determined to roll back the post-Cold War settlement, including by undermining the independence and sovereignty of the states that reemerged from the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and Soviet Union. More broadly, Russia is seeking to thwart US-led efforts to build a Europe whole, free, and at peace, and to overturn the rules-based order that has kept the general peace in Europe since the end of World War II. Moscow’s invasion and continued occupation of Georgian and Ukrainian territories, its military build-up in Russia’s Western Military District and Kaliningrad, its intervention in Syria, and its “hybrid” warfare against Western societies have heightened instability in the region and have reanimated collective defense and deterrence as an urgent mission for the United States and NATO.

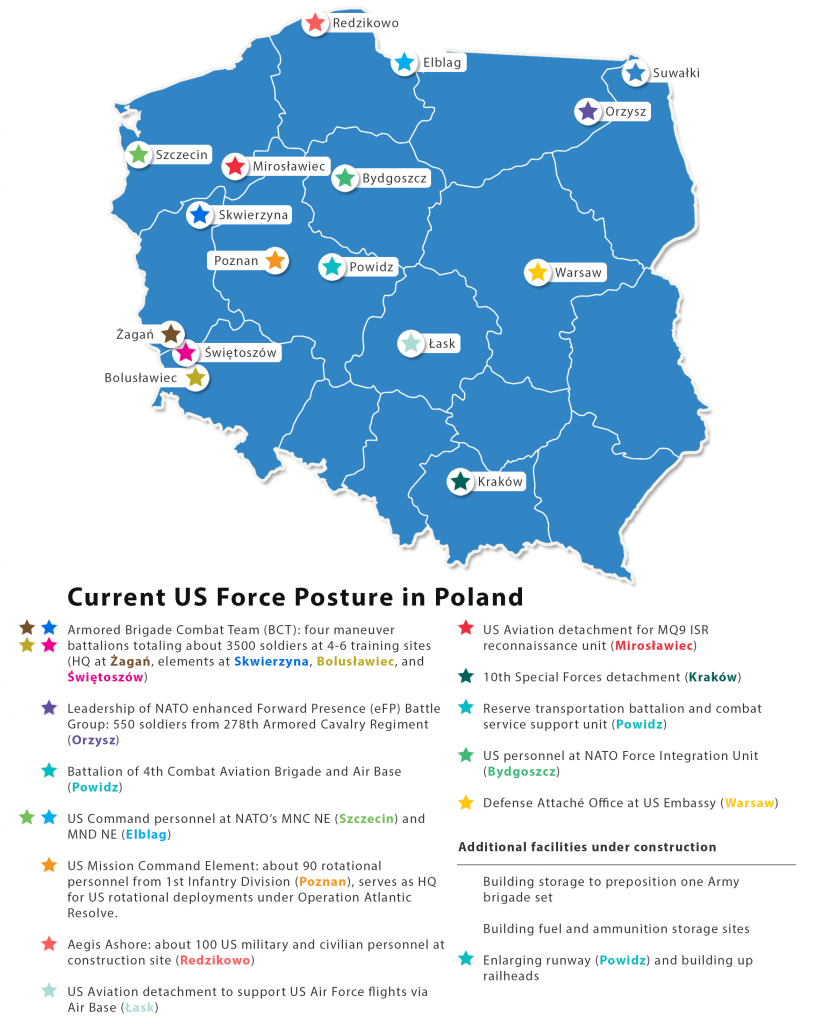

To strengthen deterrence and effectively defend against Russian aggression, the United States and NATO have taken significant steps since 2014 to enhance their force posture and respond to provocative Russian behavior. US efforts have included significantly increased investments to support the activities of the US military and its allies in Europe through the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), formerly the European Reassurance Initiative (ERI). The United States has also begun rotating an armored brigade combat team (ABCT) to Europe in “heel-to-toe” rotations every nine months, and prepositioning equipment for a second brigade combat team (BCT) that would deploy from the United States in a crisis. NATO efforts have included, among other important steps, deploying battalion-sized battle groups to each of the Baltic States and Poland through the Alliance’s enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) initiative. The United States leads the NATO eFP battalion based in northeastern Poland, near the Suwalki Corridor.

Despite these and other US and NATO efforts, the allies in North Central Europe face a formidable and evolving adversary, and it is unlikely that Russian efforts to threaten and intimidate these nations will end in the near term. Despite NATO’s overall military superiority, Russia still maintains a local tactical advantage in North Central Europe. Accordingly, the transatlantic community must reassess its response and adopt a more strategic, long-term approach to the Russian challenge. As long as the Kremlin continues on its current track, the military elements of the Alliance’s response will remain critically important, for both political and military reasons. The current US military presence in the region is predominantly rotational, which offers both geopolitical and operational advantages and disadvantages. Looking forward, assessing whether the United States should transition to a more permanent deterrence posture in the region—one that features a mix of permanent and rotational capabilities—has become timely and urgent.

It was against this backdrop that the Republic of Poland submitted to the United States in April 2018 a proposal to host, on a permanent basis, a US military division on Polish territory, and offered $2 billion to finance infrastructure for that deployment. The offer underscored Poland’s commitment to contribute to regional stability, burden sharing, and making the concept cost-effective for the US government. Still, the issue of an enhanced US presence in Europe is broader than Poland; it is fundamentally about NATO and defending all of Europe. Any decision about an enhanced US presence in Poland would have serious implications for the region, and for the Alliance as a whole.

The US Congress has expressed high interest in this Polish concept. The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2019, passed in June 2018 and signed into law on August 13, 2018, tasked the US Department of Defense with producing a report on the feasibility and advisability of establishing a more permanent presence in Poland, which is due March 1, 2019. The report requires “an assessment of the types of permanently stationed United States forces in Poland required to deter aggression by the Russian Federation and execute Department of Defense contingency plans” and “an assessment of the international political considerations of permanently stationing such a brigade combat team in Poland, including within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.2H.R. 5515, John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, (2018), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5515/text. This presents an important opportunity to catalyze a broader conversation about the United States’ and NATO’s long-term strategic approach to Russia, with military presence and force posture in the region as fundamental components of that.

During the September 2018 Washington summit between US President Donald Trump and Polish President Andrzej Duda, the US president emphasized that his administration was carefully considering the Polish offer and exploring concrete options. While the original Polish proposal sought a permanently stationed US armored division, negotiations since then have suggested a shift, with discussions moving away from one major base and toward a lighter US footprint, with rotational US personnel based at existing facilities across the country.3“Poland Wants a Fort with Donald Trump’s Name on It,” Economist, January 10, 2019, https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/01/12/poland-wants-a-fort-with-donald-trumps-name-on-it; Rick Noack, “Syria and Afghanistan are Losing U.S. Troops but ‘Fort Trump’ Talks are Going Well, Poland Says,” Washington Post, December 21, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2018/12/21/syria-afghanistan-are-losing-their-us-troops-fort-trump-talks-poland-are-going-well/?utm_term=.98b7d5f6ed98. At the time of this writing, US-Polish negotiations on this matter are ongoing.

Meanwhile, the discussions could significantly benefit from an independent perspective from outside the US government and the halls of Congress that considers these issues in the context of a broader, long- term transatlantic approach toward Russia. That is the goal of this Atlantic Council task force, established to consider the wider political and military implications of an enhanced US presence in Poland and the North Central European region.

This report and its recommendations are a product of the task force’s study of the security situation in North Central Europe, including the military balance and the threats to military stability and peace, today and in the foreseeable future. The report also reflects the group’s deliberations on the actions the United States should take to enhance deterrence and defense against aggression toward US allies in that region, which are captured in the final recommendations.

Current and anticipated security environment

The two decades following the end of the Cold War and collapse of the Soviet Union saw a significant shift in US defense priorities and resources away from Europe and toward other regions. The strategic assumption was that a post-Soviet Russia would be less antagonistic in the European security environment, and potentially a strategic partner. The United States drew down its combat forces in Europe, while European defense spending and readiness declined with the fall of the Alliance’s greatest strategic threat.

While there were signs that Russia had begun pivoting to a more hostile posture toward NATO—with cyberattacks against Estonia in 2007, the invasion of Georgia in 2008, and its subsequent major force build-up and modernization program—the United States and its NATO allies failed to fully anticipate and direct resources toward deterring the growing threat.4“How a Cyber Attack Transformed Estonia,” BBC, April 27, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/39655415. In 2014, when Russian forces invaded first Crimea and then eastern Ukraine, the United States and its allies were caught flat-footed.

Russia’s strategy and objectives

Russia has continued to be a driving factor in the European threat environment. Russia’s current strategy under President Vladimir Putin focuses on rolling back the post-Cold War settlement, including by undermining the independence and sovereignty of the states that reemerged from the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and Soviet Union. More broadly, Russia is seeking to thwart US-led efforts to build a Europe whole, free, and at peace, and to undermine the rules-based order that has kept Europe secure since the end of World War II. Key objectives to that end include weakening NATO, the European Union (EU), and other democratic institutions to create a divided Europe based on zones of influence. In fact, the Russian National Security Strategy, published in 2015 after Crimea, named the United States and its NATO allies as the primary threat to Russia.5“Russian National Security Strategy,” December 2015, paragraph 12, http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/OtrasPublicaciones/Internacional/2016/Russian-National-Security-Strategy-31Dec2015.pdf. Russia has attempted to create seams in the Alliance that it can exploit in pursuit of its aims, including attempts to cut the Baltic States off from the rest of the Alliance. Moreover, the Kremlin seeks to revise what it sees as a US-dominated world order, secure a strong voice or even a veto in key European security decisions, regain Russia’s clout as a major player on the global stage, and dominate the former Soviet space.

Accordingly, Russia has adopted a broader strategy of intimidation, underpinned by increasing hybrid actions coupled with a conventional military build-up and increasingly robust nuclear posture. This has been manifested in regions stretching from the Black Sea and Mediterranean, to the Baltic Sea and High North, and into the North Atlantic. For example, Moscow has used its conventional overmatch in the Suwalki Gap, the border between Poland and Lithuania, in attempts to intimidate the Baltic States. Russia’s constant probing has heightened instability across the transatlantic community, making the European security environment increasingly congested, contested, and susceptible to potential miscalculations and incidents.

Russia’s actions and behavior

As part of this strategic intimidation, Russia has been waging a significant hybrid warfare campaign against the transatlantic community. The Kremlin has employed a range of tools to exercise malign influence and carry out opportunistic aggression—not only in its traditional sphere of influence, but in the heart of Europe, and even in the United States. Russia’s hybrid actions include low-level conflict, such as the “little green men” maneuvers seen in Crimea, cyberattacks, disinformation, and political and economic subversion and coercion.6“Ukraine Security Agency Blames Attempted Cyberattack on Russia,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, December 5, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-cyberattack-thwarted/29638290.html Recent examples include the Skripal chemical attack in the United Kingdom, the cutting off of natural-gas pipelines to Ukraine, and the cyber and social media interference in the 2016 US elections.7Andrew Gardner, “Russia cuts gas to Ukraine,” Politico, June 16, 2016, https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-cuts-gas-to-ukraine/. These hybrid activities directly threaten, and have gradually undermined, transatlantic security, interests, and values—to the benefit of Russian aims. These actions are attempts to capitalize on diverging threat perceptions and views toward Russia within the Alliance, which has constrained collective response and further emboldened the Kremlin.

On the conventional side, increasingly aggressive behavior in the air, land, and sea has further highlighted Russia’s intent and capacity to challenge the current international security order. Russia has engaged in reckless incidents in and around Europe, such as buzzing US Navy ships and purposely violating the sovereign airspace of NATO allies.8Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “A Strange Recent History of Russian Jets Buzzing Navy Ships,” Washington Post, April 14, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2016/04/14/a-strange-recent-history-of-russian-jets-buzzing-navy-ships/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.86ea162c6cfe; Lizzie Dearden, “NATO Intercepting Highest Number of Russian Military Planes Since the Cold War as 780 Incidents Recorded in 2016,” Independent, April 22, 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/nato-russian-planes-intercepted-eu-europe-fighter-jets-scrambled-bombers-raf-typhoons-alaska-putin-a7696561.html. Moscow has increasingly attempted to assert its military power throughout Europe and the wider region, deploying forces and testing capabilities in the High North and North Atlantic that threaten to block potential reinforcements from North America.9James Stavridis, “Avoiding a Cold War in the High North,” Bloomberg, May 4, 2018, “https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2018-05-04/russia-is-gearing-up-for-a-cold-war-in-the-arctic. Russia has also maneuvered to employ advanced high-precision capabilities and project power into the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, as witnessed in its significant military campaign in Syria.10Adam Chandler, “Russia is Really Just Showing Off in Syria at This Point,” Atlantic, October 7, 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/10/russia-cruise-missiles-syria/409444/. The Kremlin announced that, overall, sixty-three thousand Russian military personnel had seen combat in Syria since September 2015, claiming to destroy “terrorist targets” and kill “militants.” Most of Russia’s involvement, however, served to consolidate the position of its ally, Syrian President Bashar al Assad, at the expense of US-backed rebel forces. “Russia Says 63,000 Troops Have Seen Combat in Syria,” BBC, August 23, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-45284121. Recently, Russia has also begun militarizing the Sea of Azov, adjacent to the Black Sea, deploying ships to block its only access point, and opening fire on and seizing Ukrainian vessels in the area.11“Russia-Ukraine Tensions Rise After Kerch Strait Ship Capture,” BBC News, November 26, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-46340283. These illegal actions heighten tensions, raise concerns that Russia is planning further action, and significantly increase the risk of miscommunication and accidents that could spiral and quickly escalate into conflict.

In a similar vein, Russia has repeatedly conducted large-scale, no-notice “snap” exercises, which many Russia watchers worry could be used to disguise a Crimea-like mass mobilization to invade elsewhere, or to leave forces or equipment behind in foreign territory such as Belarus.12Dave Johnson, “VOSTOK 2018: Ten Years of Russian Strategic Exercises and Warfare Preparation,” NATO Review, December 12, 2018, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/2018/Also-in-2018/vostok-2018-ten-years-of-russian-strategic-exercises-and-warfare-preparation-military-exercices/EN/index.htm. Moscow has also continued to ignore several of its international treaty commitments, including failing to accurately represent the size of its military exercises under the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Vienna Document, barring confidence-building Open Skies flights over Russian, Georgian, and Ukrainian territory, and violating the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), which led to the US decision to withdraw from the treaty.13This follows suit with a number of Kremlin decisions to ignore international treaty commitments, including its suspension of the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty (CFE) in 2007, and implementation issues and violations of the Open Skies Treaty (OST). See Gustav Gressel, “Under the Gun: Rearmament for Arms Control in Europe,” European Council on Foreign Relations, November 28, 2018, https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/under_the_gun_rearmament_for_arms_control_in_europe; Aaron Mehta, “US, Russia Remain at ‘Impasse’ over Open Skies Treaty Flights,” Defense News, September 14, 2018, https://www.defensenews.com/air/2018/09/14/us-russia-remain-at-impasse-over-nuclear-treaty-flights/; Daniel Boffey, “NATO Accuses Russia of Blocking Observation of Massive War Game,” Guardian, September 6, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/06/nato-russia-belarus-zapad; “Russian Compliance with the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, December 7, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/nuke/R43832.pdf.

On the nuclear side, the Kremlin has engaged in saber rattling, unveiling new types of strategic systems, including a hypersonic cruise missile designed to slip past NATO air- and missile-defense systems.14James J. Cameron, “Putin Just Bragged About Russia’s Nuclear Weapons. Here’s the Real Story,” Washington Post, March 5, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/03/05/putin-claims-russia-has-invincible-nuclear-weapons-heres-the-story-behind-this. Russia has used strong rhetoric to emphasize the concept of “de-escalatory” asymmetric strikes, which would involve limited nuclear strikes or cyberattacks in a conventional conflict to force its opponent to capitulate to its terms for peace.15US Department of Defense, 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, February 2018, 30, https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF. Though hardly new or distinctive in itself, this Russian emphasis on “escalating to de-escalate” has generated NATO concern that such threats might be employed in an effort to deter an allied response to a limited intrusion in NATO’s east. All these activities increase the risk of a second arms race in Europe between NATO and Russia, a highly destabilizing outcome.

Russia’s force posture

The Kremlin’s assertive behavior has been backed by an enhanced Russian force posture, built up over the last ten years. In the decades following the Cold War, both Russia and the United States began downsizing their military presence and posture in and around Europe. Then, after the 2008 Russia-Georgia war, in which Russia managed to occupy two “breakaway” regions of Georgia without any significant repercussions from the international community, Russia worked to build up its forces and capabilities. In light of relatively poor performance during the conflict—which highlighted the operational deficiencies of the Russian military even as it attacked a significantly smaller defender—Moscow also initiated a widespread modernization campaign, and began to increase its assertive activities around Europe’s periphery. According to a 2017 US Defense Intelligence Agency report, Russia’s defense-modernization program, the Strategic Armament Program (SAP), called for spending 19.4 trillion rubles (equivalent to $285 billion) to re-arm Russian forces from 2011 through 2020.16Defense Intelligence Agency, Russia Military Power, 2017, 20, http://www.dia.mil/Portals/27/Documents/News/Military%20Power%20Publications/Russia%20Military%20Power%20Report%202017.pdf.

Since then, Russia has continued to take steps to improve its command structure, the speed of decision-making, and communication of decisions to its forces to support rapid deployment.17Scott Boston, et al., Assessing the Conventional Force Imbalance in Europe, RAND, 2018, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2400/RR2402/RAND_RR2402.pdf. It has also enhanced interoperability among military branches, increased combat readiness, modernized former Soviet-era equipment, and created a more professional army. These efforts have produced noteworthy improvements to Russia’s warfighting capabilities, and have effectively equipped Russian forces with more modern weapons systems.18Russia Military Power, 12–13. Combine this with valuable recent combat experience from Ukraine and Syria, and the result is a starkly transformed Russian force.

Today, Russian military forces are segmented into five distinct districts, each with its own geographic focus: the Western Military District, Southern Military District, Central Military District, Eastern Military District, and Joint Strategic Command North Fleet.19Ibid., 58. The Western Military District has principal responsibility for confronting NATO, as well as supporting operations in Ukraine under the command of the Southern Military District.20Institute for the Study of War, Russia’s Military Posture: Ground Forces Order of Battle, March 2018, 12, https://www.criticalthreats.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Russian-Ground-Forces-OOB_ISW-CTP-1.pdf.

The Western Military District has also been the focus of the majority of Russia’s recent conventional build-up, which most significantly threatens NATO members in Eastern and North Central Europe. After the illegal annexation of Crimea, NATO allies have raised concerns that the former Soviet states in the region, now NATO members, could be Russia’s next targets.

The ground troops are the largest component of the Russian Armed Forces, with roughly 350,000 personnel centered around forty maneuver brigades and eight maneuver divisions.21Russia Military Power, 50. These major combat units are further operationally and administratively organized into combined-arms armies (CAA), of which the Western Military District has three, in addition to the Baltic Sea fleet. According to a report by the RAND Corporation, Russia has built up roughly eighty thousand combat personnel in the Western Military District, with almost eight hundred main battle tanks in active units or based near Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.22Boston et al., Assessing the Conventional Force Imbalance in Europe, 7–8. A major concern is that Russia’s force posture has been reorganized and repositioned, enabling it to deploy combat troops to the country’s western border very rapidly, with little warning. Russia has also improved infrastructure to facilitate quick border crossings into its western neighbors, including the three Baltic States, whose comparably smaller forces and capabilities could be quickly overwhelmed in the absence of significant US or NATO presence.23Ibid.

This posture underscores Russia’s ability to quickly generate massive manpower and firepower in its “near abroad” in Eastern and North Central Europe.

As part of the Western Military District, Russia also maintains forces in its Kaliningrad enclave. Because of the enclave’s geostrategic position between Lithuania and Poland, along with port access to the Baltic Sea, Russia has used it as a hub for powerful capabilities and as the basis for maintaining transport routes through allied territory. The territory houses a host of ground units, including two motor rifle brigades (roughly the same size as a US BCT), and artillery, missile, and anti-aircraft brigades.24Ibid. In Kaliningrad, Moscow has steadily built up its anti-access/area denial (A2AD) capabilities. This involves using integrated air defenses, counter-maritime forces, ballistic and cruise missiles, and other precision-guided munitions to create a layered array of strategic surface-to-air missiles aimed at denying an enemy’s ability to operate in the region.25Lidia Kelly, “Russia’s Baltic Outpost Digs in for Standoff with NATO,” Reuters, July 5, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato-russia-kaliningrad-idUSKCN0ZL0J7. Part of this network relies on high-precision, long-range strike capabilities, including the Iskander-M ballistic missiles and S-400 “Triumf” anti-aircraft missile system, which could be used to attack NATO installations and aircraft in the Baltics.26Ian Williams, “The Russia—NATO A2AD Environment,” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2, 2017, https://missilethreat.csis.org/russia-nato-a2ad-environment/. Charlie Gao, “NATO’s Worst Nightmare: Russia’s Kaliningrad is Armed to the Teeth,” National Interest, May 25, 2018, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/natos-worst-nightmare-russias-kaliningrad-armed-the-teeth-25958.

Kaliningrad also hosts a growing Russian naval presence with the Baltic Sea fleet. The fleet includes several ships and submarines capable of firing long-range Kalibr cruise missiles. Other Baltic Sea fleet assets include a destroyer, six frigates, and seven corvettes, which carry advanced anti-ship missiles and provide additional anti-surface, anti-submarine, and anti-air warfare capabilities.27Charlie Gao, “NATO’s Worst Nightmare: Russia’s Kaliningrad is Armed to the Teeth,” National Interest, May 25, 2018, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/natos-worst-nightmare-russias-kaliningrad-armed-the-teeth-25958. Together, the Russian navy and air force also maintain roughly eighty fighter aircraft and more than one hundred ground-attack aircraft in the district, supported by powerful electronic-warfare and advanced technological capabilities that can be employed in the region, reducing a previously stark gap with the United States and NATO.28“Chapter Five: Russia and Eurasia,” in The Military Balance (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2017), 202, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/04597222.2018.1416981.

Together, these capabilities create a potential threat to US or NATO forces attempting to enter North Central Europe to defend or reinforce the region in a potential crisis. While Russia’s posture would not stand up to the United States or NATO in the long term, denying or contesting US or allied forces’ ability to maneuver in the region could impede or delay their response long enough for Russia to achieve a fait accompli. Given Russia’s readiness, proximity, and ability to quickly mass firepower close to its borders, along with its demonstrated behavior and objectives in the region, North Central Europe remains arguably the most vulnerable potential flashpoint between Russia and the United States and NATO.

Russia has also extended its provocative force posture farther south; Moscow has been militarizing the Crimean Peninsula since its illegal annexation of the territory in 2014. Russia established an army corps, supported by a long-range coastal air-defense brigade.29“The Shore of Russia was Covered by ‘Rocket Monsters,’” Izvestiya, January 7, 2018, https://iz.ru/680351/nikolai-surkov-aleksei-ramm-evgenii-dmitriev/poberezhe-rossii-prikryli-raketnye-monstry. It also built up its naval and air assets, deploying twelve SU-30 fighter jets, helicopters, an additional six submarines, three frigates, a coastal radar complex for surveilling NATO maritime activity, and its S-400 air-defense system on the Crimean Peninsula.30Dmitry Gorenburg, “Is a New Russian Black Sea Fleet Coming? Or Is It Here?” War on the Rocks, July 31, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/07/is-a-new-russian-black-sea-fleet-coming-or-is-it-here; “Russia to Continue Deploying Advanced S-400 Air Defense Missile Systems in Crimea,” Tass, May 4, 2018, http://tass.com/defense/1002861. Russia has used the strategic location of the peninsula to create a second A2AD bubble in the region, from which Moscow could strike targets in Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East.31Ruslan Minich, Russia Shows its Military Might in the Black Sea and Beyond, Atlantic Council, November 6, 2018, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/russia-shows-its-military-might-in-the-black-sea-and-beyond. This significant military footprint has provided Russia strategic access to the Black Sea, which threatens NATO assets and territory, and could allow the Kremlin to extend its influence and power projection toward the Mediterranean Sea and the Balkan States, and into North Central Europe.

Against the backdrop of this assertive force posture on NATO’s borders, Russia has also developed and boasted about its nuclear arsenal, including a long-range, ground-launched cruise missile—in violation of the INF Treaty—and controversial low-yield and tactical nuclear weapons, which Russia’s doctrine suggests it could use at dangerously low thresholds of conflict. Compounding that, its recent iterations of the major Zapad and Vostok exercises have highlighted Russia’s ability to rapidly coordinate, mobilize, and deploy large military formations that include advanced air defense, armored formations, and long-range strike capabilities.32The Zapad and Vostok exercises are part of Russia’s four annually rotating regional training operations that tests military strategy and troop preparedness by simulating war. For more, see https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/09/13/5-things-to-know-about-russias-vostok-2018-military-exercises/?utm_term=.8631776edfe8 and https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/articles/zapad-2017-a-guide-to-russia-s-largest-military-exercise. Taken together, Russia’s readiness, proximity, advanced capabilities, and ability to quickly mass significant firepower showcase Russia as a more formidable and emboldened opponent than has been seen since the Cold War—one that NATO and the United States must address with their own enhancements to defense and deterrence in the

Looking ahead: the future of the Russian threat and other emerging threats

The Kremlin’s current and foreseeable course of action is largely driven by internal political dynamics inside Russia, which are not likely to change in the near term. The legitimacy of Putin’s regime, strained by a struggling economy but not likely to fall soon, is underpinned by the narrative of “encirclement of Russia by a hostile West.” This provides the pretext for Russia to demonstrate its power on the world stage. As a result, Moscow will continue to assert its interests most boldly in its sphere of influence in Eastern and North Central Europe, and may do so with force when it deems that necessary, or when the Kremlin sees a low-cost opportunity to increase its political or military power. However, Putin will avoid actions he believes would provoke a major military response from the United States and NATO, making the Alliance’s deterrent posture even more crucial. If Putin questions the credibility of NATO’s deterrence, because of perceived military inadequacy or alliance disunity, a carefully calculated military action on allied territory is not unimaginable. For these reasons, Russia’s current conventional overmatch in North Central Europe, especially in the Baltic States—although it has been mitigated by NATO since 2014—remains a matter of serious concern for the Alliance.

Meanwhile, the Kremlin will seek to exploit the narrative that the West is weak, and is divided over internal disputes and differences between Washington and its European allies. The Kremlin will continue to increase the intensity, complexity, and scope of its hybrid and cyber activities, in attempts to destabilize Western societies and discredit democratic values. Russia will also likely continue to ignore its international treaty obligations, in an effort to undermine the security architecture set by the United States and Europe.

Despite a further decline in 2018 to 2.771 trillion rubles ($41.5 billion), Russian defense spending is expected to grow again, to 2.808 trillion rubles ($42.1 billion) in 2020.33Sergey Zhavoronkov, “Two Lean Years: Russia’s Budget for 2018–2020,” Russia File (blog), Wilson Center, December 8, 2017, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/two-lean-years-russias-budget-for-2018-2020. Russia will continue to develop and modernize its capabilities, including through the introduction of new electronic, cyber, and hypersonic technologies. The Kremlin has already demonstrated a new focus on advancing high-precision strike capabilities, as part of what it deems as “pre-nuclear deterrence.” General Curtis M. Scaparrotti, NATO supreme allied commander Europe and commander of US European Command, has emphasized that if the United States does not keep up its modernization efforts, the pace of Russia’s efforts “would put us certainly challenged in a military domain in almost every perspective by, say, 2025.”34Patrick Tucker, “Russia Will Challenge US Military Superiority in Europe by 2025: US General,” Defense One, March 8, 2018, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2018/03/russia-will-challenge-us-military-superiority-europe-2025-us-general/146523/.

At the same time, Russia is expected to further modernize, if not increase, its nuclear arsenal—including tactical, short-range, and Iskander-class capabilities—and re-nuclearize Crimea.35“Russia Deploys Nuclear Weapon Carriers in Occupied Crimea—Yelchenko,” Unian Information Agency, December 6, 2018, https://www.unian.info/politics/10365714-russia-deploys-nuclear-weapon-carriers-in-occupied-crimea-yelchenko.html. Russia’s continued ambiguity regarding its doctrine and “escalate to deescalate” strategy will force NATO to consider the possibility that the Kremlin will use asymmetric, or even nuclear, capabilities to settle a conventional conflict on its terms. This has significant implications for the United States and NATO—in terms of force posture, but also potentially strategy and doctrine.

Signs indicate that Russia will sustain its large-scale exercises and increase their complexity, maintaining and honing the ability to rapidly mass conventional forces with little warning. This enhances Russia’s ability to prepare for potential offensive operations that could overwhelm forces on NATO’s borders, increases the chances of Russia using a snap exercise to disguise another illegal intervention abroad, and raises the risks that a miscalculation by a NATO ally or Russia could escalate to full-scale conflict.

Looking to the future, the global threat environment may evolve in other ways, with growing instability emanating from the Arctic, China, Iran, and beyond. China continues to pose a challenge as a great-power competitor, while challenges to the nonproliferation regime from Iran and North Korea, as well as the developing impacts of climate change, could represent further threats for the United States and the transatlantic community in the coming years.

Against this backdrop, the United States must be able to strategically deploy its limited resources around the world. As Europe is the United States’ closest and most important ally, its security is critical to the USglobal agenda. Russia now represents the most serious threat since the end of the Cold War to the collective peace and security that the United States and its allies in Europe have fought so hard to rebuild and preserve. To be sure, the Russian challenge, both in Europe and elsewhere, is only one aspect of the current and anticipated security environment, but a significant and pressing one. The US National Defense Strategy underscores this with its focus on great-power competition and Russia, providing the strategic impetus and groundwork for action. The United States and its allies must bolster defense and deterrence against Russia, particularly where the Alliance is most vulnerable in North Central Europe. Steps have been taken, but more can be done to meet this long-term challenge.

The US and NATO response

Recognizing the resurgence of Russia as a strategic competitor, the United States and NATO have taken several significant steps to respond to multiple aspects of the Russian challenge.

On the political, economic, and other non-military fronts, some notable progress has been made since 2014. The United States spearheaded sanctions, some multinational with EU partners, to punish Russia for its illegal annexation of Crimea, hybrid war and aggression in Eastern Ukraine, its cyber and critical-infrastructure attacks, and its interference in elections in the United States and Europe.36Mark Landler, Annie Lowrey, and Steven Lee Myers, “Obama Steps Up Russia Sanctions in Ukraine Crisis,” New York Times, March 20, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/21/us/politics/us-expanding-sanctions-against-russia-over-ukraine.html; Allan Smith, “U.S. Imposes New Russia-Related Sanctions, Citing Election Interference, ‘Other Malign Activities,’” NBC News, December 19, 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/u-s-imposes-new-russia-related-sanctions-citing-election-interference-n949991. The United States, with the support of Congress, also established the Global Engagement Center (GEC) at the Department of State to counter Russian disinformation and influence operations in Europe and Eurasia—though many assert that more resources and authorities are required for the GEC to have a real impact.37Gardiner Harris, “State Dept. Was Granted $120 Million to Fight Russian Meddling. It Has Spent $0,” New York Times, March 4, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/04/world/europe/state-department-russia-global-engagement-center.html. NATO has created its own Hybrid Analysis Branch focused largely on Russia, signed a watershed joint declaration to boost NATO-EU cooperation against hybrid threats, and, alongside the EU, supported the establishment in Helsinki of a multinational European Center of Excellence (COE) for Countering Hybrid Threats.38European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, “Common Set of Proposals for the Implementation of the Joint Declaration by the President of the European Council, the President of the European Commission and the Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization,” December 6, 2016, https://www.hybridcoe.fi/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Common-set-of-proposals-for-the-implementation-of-the-Joint-Declaration-2.pdf. Many European allies have also sharpened their approaches for holistically tackling Russian malign influence.

On the military front, the United States and NATO have also made important strides by adapting their force posture, as described in more detail below.

NATO and US force posture in Europe pre-2014

At the height of the Cold War, the United States, as the driving force behind NATO, had upward of three hundred thousand personnel deployed to Western Europe, operating as a deterrence by denial force. Posture in Europe was centered around four divisions and five brigade combat teams, primarily located in Germany, the expected point of attack for Soviet forces. 39Kathleen H. Hicks, et al., Evaluating Future U.S. Army Force Posture in Europe (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2016), https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/160712_Samp_ArmyForcePostureEurope_Web.pdf. These NATO forces were supplemented by major stockpiles of equipment for further reinforcements in the event of a war. NATO routinely trained this capability in REFORGER exercises, which transported large-scale reinforcements from the United States to West Germany, and ensured NATO had the ability to rapidly return forces to Europe in the event of a conflict with the Soviet Union.40“Countdown to 75: US Army Europe and REFORGER,” US Army, March 22, 2017, https://www.army.mil/article/184698/countdown_to_75_us_army_europe_and_reforger.

The end of the Cold War eliminated the basis for this American force posture in Europe. The collapse of the Soviet Union removed an urgent and significant military threat, and Russia under the leadership of President Boris Yeltsin generated hopes for a genuine and lasting partnership between the West and Moscow. In the years that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall, notwithstanding conflict in the Balkans, the United States began decreasing its military footprint in Europe. In the late 1990s, the United States maintained four brigades permanently in Europe, housed under two divisions—the 1st Armored Division and 1st Infantry Division—in Germany, with an airborne brigade in Italy.41Ibid.

In the early 2000s, with growing European integration, relative peace and stability on the European continent, and rising demands for US forces in the Middle East and elsewhere, US military leadership asserted that the United States could fulfill its commitments to an enlarged NATO with fewer forces in Europe. In 2004, President George W. Bush’s administration decided to remove the heavy armored brigades of the 1st Armored Division and 1st Infantry Division back to the United States, along with their enablers and headquarters elements, as part of the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) commission in 2005.42Gary Sheftick, “Army Planning Drawdown in Europe,” US Army, March 26, 2012, https://www.army.mil/article/76339/army_planning_drawdown_in_europe. This move was later paused, in part due to infrastructure concerns in the United States.43“Lawmakers Scramble to Save Bases,” CNN, May 14, 2005, http://www.cnn.com/2005/POLITICS/05/13/base.closings/. In 2012, citing a downsizing of the US Army and a new focus on the Asia-Pacific region, the Barack Obama administration carried out the removal of these two brigades long stationed in Germany, and brought home all the US tanks and other heavy vehicles prepositioned in Europe. This left the US Army, the primary component of US forces in Europe, with just two light BCTs and approximately sixty-five thousand total US personnel stationed in Europe by 2014.44Philip Breedlove, statement to the House Armed Services Committee, February 25, 2015, www.eucom.mil/media-library/…/u-s-european-command-posture-statement-2015.

Still, throughout those years, the NATO Alliance maintained a modest, but important, presence on Europe’s eastern flank, particularly to support its newest allies. Since 2007, NATO has maintained a Baltic Air Policing mission over Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, a Joint Force Training Center (JFTC) in Bydgoszcz, Poland, under NATO’s Allied Command Transformation, and the Multinational Corps Northeast (MNC-NE) in Szczecin, Poland.45Paul Belkin, Derek E. Mix, and Steven Woehrel, “NATO: Response to the Crisis in Ukraine and Security Concerns in Central and Eastern Europe,” Congressional Research Service, July 31, 2014, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R43478.pdf. MNC-NE was established by framework nations Germany, Denmark, and Poland to assist with the collective defense of NATO territory, contribute to multinational crisis management including peace-support operations, and provide command and control for humanitarian, rescue, and disaster-relief operations. This grew to include fourteen contributing nations by 2014. However, in the early 2000s, many of its personnel were assigned to NATO’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission in Afghanistan, reflecting the West’s rising focus on counterterrorism. Despite this shift, the United States continued to contribute a four-aircraft rotation to the Baltic Air Policing Mission, and maintained a small number of troops at both MNC-NE and the JFTC.

NATO force posture in Europe post-2014

Notwithstanding Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008, the transatlantic community was shocked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014—including the illegal annexation of Crimea and the seizure of territory in eastern Ukraine by Russian-led forces—as well as the Kremlin’s demonstrated capacity for hybrid warfare in eastern Ukraine and against Western democratic institutions. In response, the United States and NATO began to quickly rebuild their defense-and-deterrence posture in Europe, while also increasing assistance to non-NATO countries on NATO’s periphery, to allow them to defend their territory from ongoing and potential Russian attack and subversion.

The Alliance’s initial response to the invasion of Ukraine, a non-NATO nation on its frontier, was “assurance measures” focused on air defense and surveillance, maritime deployments, and military exercises. The primary focus was Europe’s northeast, where allied territory was most vulnerable because of its geographic proximity with Russia. NATO increased the Baltic Air Policing mission from four to sixteen aircraft, and NATO AWACS conducted sustained missions over Poland and Romania to monitor events in Ukraine.46Ibid. In the maritime domain, NATO deployed two maritime groups on patrol to the Baltic and Mediterranean Seas.47Ibid. Outside of NATO’s existing exercise regimen, NATO member states conducted a series of military drills in the Baltics, such as a drill in Estonia with six thousand participating allied troops, aimed at repelling a potential attack on Estonian territory.48Ibid. Some allies, particularly the Baltic States, called for a more robust response, one that included the permanent stationing of troops in NATO’s east.49Richard Milne, “Baltics Urge NATO to Base Permanent Force in Region,” Financial Times, April 9, 2014, https://www.ft.com/content/86e4a4cc-bfb5-11e3-9513-00144feabdc0.

At the NATO Wales Summit in September 2014, seven months after the invasion of Crimea and with escalating Russian-Ukrainian hostilities in eastern Ukraine, Alliance leaders promulgated a Readiness Action Plan designed to combine some of the short-term “assurance measures” already in place with “adaptive measures” that offered a longer-term response to Russian aggression.50NATO’s Readiness Action Plan, July, 2016, NATO, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2016_07/20160627_1607-factsheet-rap-en.pdf The Readiness Action Plan centered around building up NATO’s reinforcement capabilities, rather than building a permanent conventional deterrence structure. The plan increased the size of the NATO Response Force (NRF), nearly tripling it from thirteen thousand to forty thousand personnel, and incorporating land, sea, air, and special-forces components.51Ibid. Within the NRF structure, NATO created the Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF), a quick-reaction force of five thousand personnel designed to respond to a crisis within a matter of days. Allies also established NATO force integration units (NFIU), small teams staffed to support defense planning and facilitate rapid reinforcement, and deployed them to the Baltic States, Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria.52Ibid. Other adaptation measures included the establishment of a new multinational division for the southeast in Romania, prepositioning, and preparation of infrastructure to support reinforcement.53Ibid.

NATO’s existential deterrence strategy, implemented through the Wales Summit initiatives, relied heavily on the existence of these relatively small spearhead units. While it reduced the arrival time for NATO reinforcements, many judged this limited rapid-reaction capability insufficient to deter Russian aggression, whether large-scale conventional attack or a scenario involving ambiguous hybrid methods, such as those Moscow demonstrated in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. Many allied and NATO leaders made it clear that a more significant military response was required, calling for a “sufficiently robust and multinational forward presence backed up by swift reinforcements,” to signal to Russia that the cost of breaching NATO borders would be too high.54Alexander Vershbow, “A Strong NATO for a New Strategic Reality,” (keynote address at the Foundation Institute for Strategic Studies, Krakow, March 4, 2016), https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_128809.htm.

At the July 2016 Warsaw Summit, the Alliance took that next step by deploying its enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) battle groups, a ground combat force, to Eastern and North Central Europe, still the most significant potential flashpoint for a conflict with Russia. Allied leaders agreed to deploy four multinational NATO battle groups to each of the Baltic States and Poland, on a rotational basis. The presence, which became operational in 2017, used the framework-nation model, with the United States leading the battalion in Poland, the United Kingdom leading in Estonia, Germany leading in Lithuania, and Canada leading in Latvia. In early 2018, this presence numbered more than 4,600 troops, with seventeen contributing nations.55“NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence,” NATO, February 2018, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2018_02/20180213_1802-factsheet-efp.pdf.

This eFP mission transitioned NATO’s defense of North Central Europe to a strategy of deterrence by trip wire. The location of eFP battalions and their multinational character are intended to make clear to Russia that any aggression would be met immediately—not just by local forces, but by forces from across the Alliance. As the Warsaw Communique states, the battle groups “unambiguously demonstrate, as part of our overall posture, Allies’ solidarity, determination, and ability to act by triggering an immediate Allied response to any aggression.”56NATO, press release, “Warsaw Summit Communiqué,” July 9, 2016, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm. In Warsaw, the Alliance also declared cyber an operational domain.57Colin Clark, “NATO Declares Cyber a Domain; NATO SecGen Waves Off Trump,” Breaking Defense, June 14, 2016, https://breakingdefense.com/2016/06/nato-declares-cyber-a-domain-nato-secgen-waves-off-trump/. Amid a growing number of cyber incidents and hack-and-release tactics by Russia against the United States and Europe, this empowered the Alliance to coordinate and organize its efforts to protect against cyber threats in more efficient and effective ways, thereby increasing deterrence.

While eFP marked a significant increase in allied force presence in North Central Europe, the combination of these forward-deployed elements and host-nation forces still faced significantly larger, and more heavily armored, combined Russian forces immediately across the border. Thus, defending North Central Europe in a crisis would immediately require substantial reinforcements from elsewhere in Western Europe, or even the United States. These forces would take time to mobilize and deploy, giving Russia a limited window for opportunistic aggression, which could result in a fait accompli and require the Alliance to undertake costly offensive action to reacquire territory seized by Moscow.

At its July 2018 Brussels Summit, NATO sought to shorten this time-distance gap.58NATO, press release, “Brussels Summit Declaration,” July 11, 2018, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_156624.htm. The NATO Readiness Initiative (NRI), the so-called “Four 30s” plan, requires thirty ground battalions, thirty air squadrons, and thirty major naval combatants ready to deploy and engage an adversary within thirty days. NATO also undertook significant command-structure reform, to help address this problem and ensure the structure was fit for purpose in today’s security environment. As part of the more robust command structure, allied leaders agreed to establish a Joint Support and Enabling Command (JSEC) in Germany to facilitate the support and rapid movement of troops and equipment across Europe, and a Joint Force Command Norfolk to protect crucial sea lines of communication and transport between North America and Europe. In a related effort, NATO and the EU have also collaborated on a “military mobility” initiative, under Dutch leadership, which seeks to facilitate the rapid movement of forces and equipment across the European continent, especially as it relates to border crossings, infrastructure requirements, and legal regulations.59Current efforts seek to ensure diplomatic clearance for force movements within five days of their reaching a border. In light of increasingly aggressive cyber incidents perpetrated by Russia, at the Brussels Summit NATO also established a Cyber Operations Center. The center was designed to coordinate NATO’s cyber deterrent and nations’ capabilities, through a team of experts fed with military intelligence and real-time information on threats in cyberspace. When operational, the center could help boost deterrence by potentially using offensive cyber capabilities provided by nations to take down enemy missiles, air defenses, or computer networks, in appropriate circumstances.

These decisions from the Wales, Warsaw, and Brussels Summits have accumulated and evolved, laying the groundwork for deterrence by rapid reinforcement, the Alliance’s current strategy for defending its eastern frontier.

To facilitate these efforts, European allies and Canada have also taken steps to halt the drop in defense spending that had undercut allied deterrence. In 2014, only three allies—the United States, the United Kingdom, and Greece—met NATO’s 2-perent-of-GDP defense-spending target, and only seven allies spent 20 percent of their defense budgets on major equipment, as required by NATO’s benchmark. Since 2014, European allies and Canada have added $46 billion to their defense budgets.60“Secretary General’s Annual Report: The Alliance is Stepping Up,” NATO, March 17, 2018, 6, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_152805.htm Eight allies are expected to have met the 2-percent threshold in 2018, and the majority have plans to reach that mark by 2024, as allies pledged to do at the Wales Summit.61Ryan Heath, “8 NATO Countries to Hit Defense Spending Target,” Politico EU, May 7, 2018, https://www.politico.eu/article/nato-jens-stoltenberg-donald-trump-8-countries-to-hit-defense-spending-target/; “Secretary General’s Annual Report: The Alliance is Stepping Up,” NATO.

US forces posture in Europe post-2014

The drawdown of US troop levels in Europe since the end of the Cold War—particularly the 2012 downsizing of the US Army presence from four to two BCTs—had raised concerns among commanders at EUCOM and in the Office of the Secretary of Defense. However, it was not until the events of 2014 that those views were shared widely in the White House and Pentagon.62Hicks et al., Evaluating Future US Army Posture in Europe, 15. In conjunction with the Readiness Action Plan laid out at the 2014 Wales Summit, the United States reacted quickly to reassure Eastern and Central European allies of its dedication to the Alliance’s collective-defense mission.

Immediately after Russian troops entered Crimea, EUCOM deployed company-level elements from army units based in Europe to Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland as an immediate reassurance measure.63Jesse Granger, “173rd Conducts Unscheduled Training with Latvian Army,” US Army Europe Public Affairs, April 25, 2014, https://www.army.mil/article/124667/173rd_conducts_unscheduled_training_with_latvian_army. The United States also recognized a need for deterrence in the air domain, deploying six F-15s to the Baltic Air Policing mission, along with an aviation detachment of twelve F-16s to Łask, Poland.64Belkin, et al., “NATO: Response to the Crisis in Ukraine and Security Concerns in Central and Eastern Europe.” This tripwire force, similar in doctrine to NATO’s subsequent eFP deployments, allowed the United States to immediately reinforce the collective defense-and-deterrence mission, while it slowly expanded deployments and funding. Many of these efforts were supported by the FY2015 European Reassurance Initiative (ERI), a watershed military program launched by the Obama administration as part of Operation Atlantic Resolve. ERI, which later became the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), has continued to expand under the Trump administration, providing significant funding to support US presence, exercises and training, enhanced prepositioning, and improved infrastructure throughout Europe.

From there, under the auspices of ERI, the United States continued to slowly augment its presence, particularly in North Central Europe which is the focal point of potential confrontation with Russia. Nearly two years after Crimea, the United States had added roughly four thousand additional rotational troops to Europe, in addition to the BCTs already permanently deployed to Europe: the Germany-based 2nd Cavalry Regiment at Vilseck and the Italy-based 173rd Airborne BCT at Vicenza. In Grafenwöhr, the United States also maintains the Grafenwöhr Training Area—its largest training facility in Europe—which supports US and NATO force qualifications.657th Army Training Command, http://www.7atc.army.mil/.

Recognizing the longer-term nature of strategic competition with Russia, during the discussion of the 2017 NDAA, the US Congress changed ERI’s name to EDI to reflect the evolution of the mission from reassuring allies to deterring Russia. Acknowledging that current US and allied forces in North Central Europe were insufficient for deterrence purposes, in 2017 the United States also began the nine-month, heel-to-toe armored brigade combat team (ABCT) rotations to Europe, supported by EDI. These continue today in Poland, with detachments deploying regularly throughout Central Europe.66Michelle Tan, “Back-to-Back Rotations to Europe Could Stress the Army’s Armored BCTs,” Army Times, February 11, 2016, https://www.armytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2016/02/11/back-to-back-rotations-to-europe-could-stress-the-army-s-armored-bcts/. Before the arrival of the first rotational brigade, the US Army filled the gaps with Regionally Allocated Forces (RAF) from the 1st BCT, 3rd Infantry Division, of Fort Stewart, Georgia. Between their rotation cycles, soldiers from 2nd Cavalry Regiment and the 173rd Airborne BCT filled in.67Ibid. These rotations now provide periods during which US forces are systematically postured closer to the frontline of a potential conflict in North Central Europe, to further reduce the time-distance gap and enhance deterrence in the region.

While certainly nowhere near its Cold War level, US posture in Europe is markedly different today than it was four years ago, with a strong emphasis on deterrence by rapid reinforcement and the rotational presence of forward-deployed combat units. The US Army in Europe (USAREUR) currently maintains thirty-five thousand US soldiers in theater, with twenty-two thousand permanently assigned to USAREUR. The US Army presence in Europe includes the 12th Combat Aviation Brigade (CAB), USAREUR Headquarters, the 21st Theater Sustainment Command, the 16th Sustainment Brigade, the 10th Army Air and Missile Defense Command, the 7th Army Joint Multinational Training Command, the 66th Military Intelligence Brigade, and the 5th Signal Command, which provide headquarters and enabler units including rotary-wing assets, command and control, logistics, sustainment, intelligence, and engineering support.68“Evaluating Future US Army Posture in Europe,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 29, 2016, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/160712_Samp_ArmyForcePostureEurope_Web.pdf. The US Army also employs 12,500 local nationals, eleven thousand civilian officials from the US Department of the Army, and RAF rotating through as part of Atlantic Resolve.69“Fact Sheet: U.S. Army Europe,” US Army Europe Public Affairs Office, November 14, 2018, http://www.eur.army.mil/Portals/19/documents/20181114USArmyEuropeFactSheet.pdf?ver=2018-11-14-105314-843. In 2018, USAREUR participated in fifty-two exercises to enhance readiness and interoperability of these forces, with approximately twenty-nine thousand US personnel and more than sixty-eight thousand multinational participants from across forty-five countries.70Ibid.

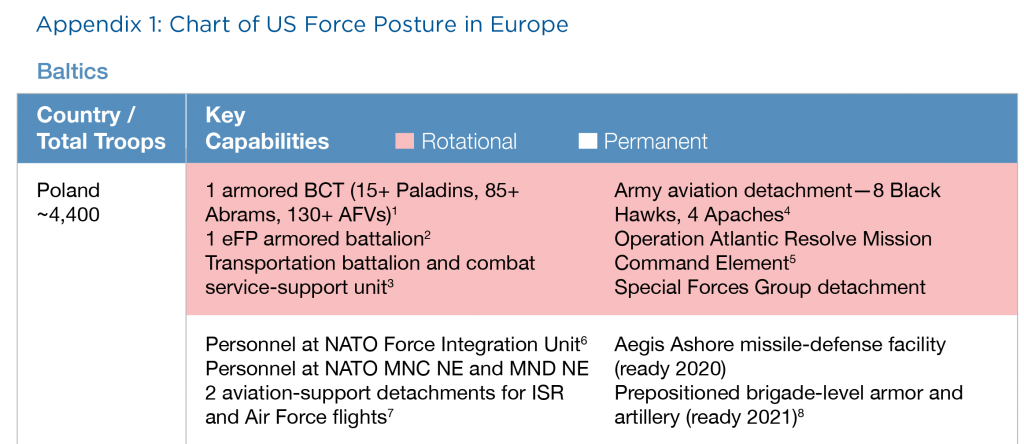

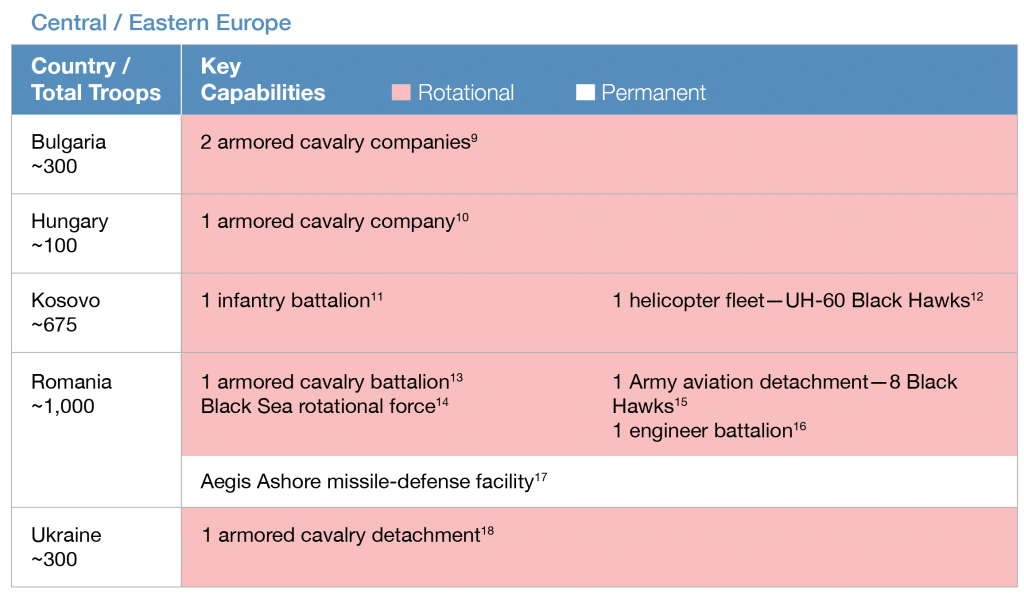

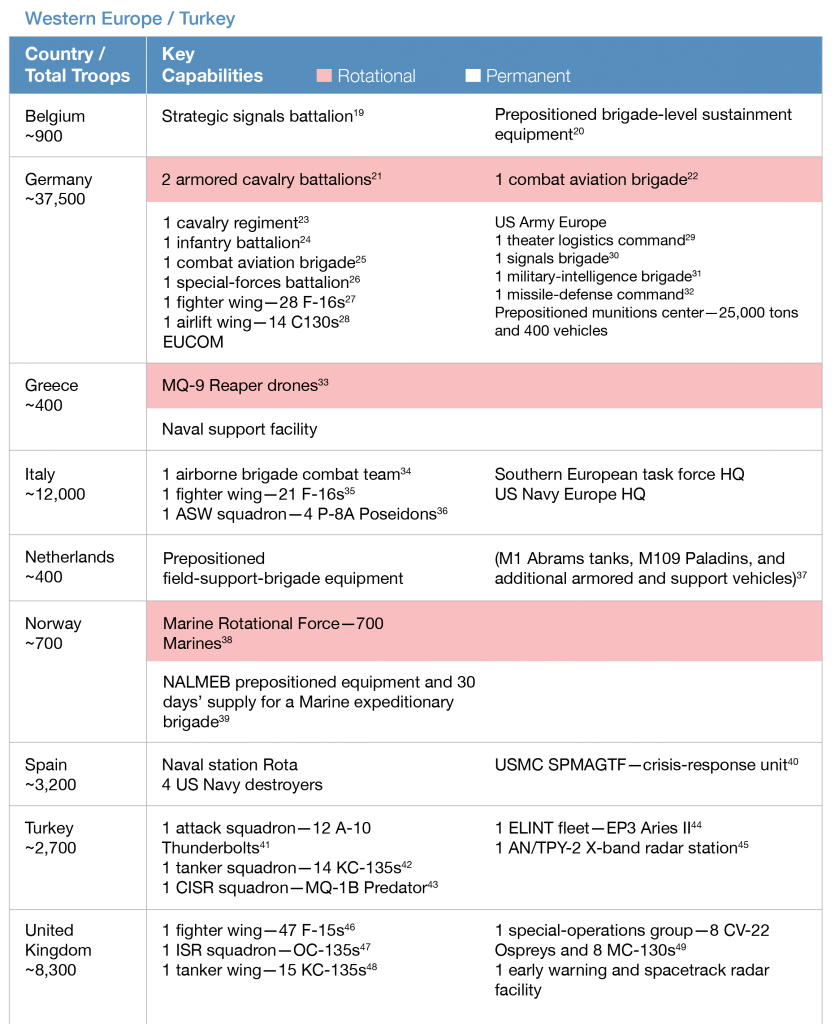

In addition to its major Army units, the United States’ European Command (EUCOM) has at its disposal a number of other land, air, and naval assets in its area of operations, totaling more than sixty thousand military and civilian personnel.71“EUCOM Posture Statement 2018,” EUCOM, March 8, 2018, https://www.eucom.mil/mission/eucom-posture-statement-2018. Significant units are listed below.

- There is a sizeable military presence in Germany, which, alongside the permanently stationed cavalry regiment, includes: a permanently stationed combat aviation brigade (CAB) and a rotational CAB operating in support of Atlantic Resolve; a special-forces battalion; theater-level training, air and missile defense, battlefield-coordination, and theater-sustainment commands; a fighter wing of twenty-eight F-16s; and an airlift wing of fourteen C130s.72“Fact Sheet: U.S. Army Europe,” US Army Europe Public Affairs Office. The additional rotating CAB, which offers a combination of attack/reconnaissance helicopters (AH-64 Apache), medium-lift helicopters (UH-60 Black Hawk), and heavy-lift helicopters (CH-47 Chinook), provides a significant supplemental capability to the region.

- In the high north in Norway, the US Marine Corps maintains a battalion-sized rotational presence, alongside a brigade-level prepositioning site under the Norway Air-Landed Marine Expeditionary Brigade (NALMEB) program.73Ryan Browne, “US to Double Number of Marines in Norway Amid Russia Tensions,” CNN, June 12, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/06/12/politics/us-marines-norway-russia-tensions/index.html.

- In the United Kingdom, the US Air Force maintains a supplemented fighter wing of forty-seven F-15s alongside a tanker wing, an intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) squadron, and a special-operations wing composed of CV-22 Ospreys and MC-130 Hercules aircraft.

- In Southern Europe, EUCOM maintains a range of air, land, and sea assets, with a naval station in Rota, Spain, currently supporting: four US Navy Aegis destroyers; a permanently stationed airborne BCT, F-16 fighter wing, and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) squadron in Italy; a naval support facility in Souda Bay, Greece; and attack, tanker, and ISR squadrons stationed at Incirlik, Turkey, used to support operations against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS).

- The Atlantic Resolve BCT and CAB rotations are deployed throughout Central Europe, with company-level detachments rotating through Bulgaria and Hungary, and a battalion from the BCT deploying to Romania, coupled with an aviation detachment and engineer battalion. Romania also hosts a permanent Aegis Ashore missile-defense facility.

- In addition, the United States maintains several prepositioned stock sites in Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands, which can outfit an armored BCT, whose personnel would be flown in from the continental United States (CONUS).

Over the last four years, EDI has continued to grow, reaching a $6.5 billion budget request for FY2019.74US Department of Defense, “Department of Defense Budget Fiscal Year (FY) 2019, European Deterrence Initiative,” https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2019/fy2019_EDI_JBook.pdf. One major output from the FY2018 EDI was the prepositioning of Air Force equipment and airfield infrastructure improvements to support current operations, exercises, and activities, and to enable a rapid response to contingencies.75“2018 European Deterrence Initiative (EDI) Fact Sheet,” EUCOM, October 2, 2017, https://www.eucom.mil/media-library/document/36100/2018-european-deterrence-initiative-edi-fact-sheet. The FY2019 budget builds on this, funding European Contingency Air Operations Set (ECAOS) Deployable Airbase System (DABS) prepositioned equipment at various locations throughout Europe.76US Department of Defense, “Department of Defense Budget Fiscal Year (FY) 2019, European Deterrence Initiative. This provides a basis for implementing the concept of adaptive basing for air forces as an important element of NATO’s reinforcement strategy. The FY2019 EDI also supports “the continued buildup of a division-sized set of prepositioned equipment that is planned to contain two armored BCTs (one of which is modernized), two Fires Brigades, air defense, engineer, movement control, sustainment and medical units.”77Ibid., 11. USAREUR has identified Powidz Air Base, Poland, as a brigade-level prepositioning site.78“Fact Sheet: Army Prepositioned Stock,” US Army Europe Public Affairs Office, September 13, 2018 http://www.eur.army.mil/Portals/19/Fact%20Sheets/FactSheet-APS.pdf?ver=2019-01-22-110643-650. Additional EDI funding is also designated for ammunition and bulk fuel storage, rail extensions and railheads, a staging area in Poland, and ammunition infrastructure in Bulgaria and Romania, which is a welcome development.79US Department of Defense, “Department of Defense Budget Fiscal Year (FY) 2019, European Deterrence Initiative,” 25.

Assessing the response

The United States and NATO have taken significant steps to respond to Russia’s significant military build-up and aggression, by first implementing a deterrence by tripwire strategy and then a deterrence by rapid reinforcement strategy. Still, the evolution and implementation of these responses have been incremental, temporal, and reactive. Most importantly, the forces deployed under these strategies have not sufficiently addressed time, space, and mass advantages currently leveraged by Russia. Given the enduring nature of the Russian challenge, the United States, along with its NATO allies, must reassess its approach to account for long-term strategic competition with Russia.

Certainly, the United States and NATO have made strides toward responding to Russia’s provocative behavior, including when it comes to hybrid and cyber activities. But, overall, allied retaliatory measures have not been sufficient to change Putin’s calculus in Ukraine or elsewhere. Going forward, the United States and NATO must implement a more strategic and long-term approach toward Russia, using the full range of political, economic, military, and other responses.

The need for an enhanced force posture

The conventional military pillar of this approach remains fundamental to deterring Russia. The United States and NATO face a pressing need to adjust their posture to strengthen defense and deterrence, given the vulnerability of North Central Europe. NATO’s current defense-and-deterrence posture relies on the certainty that the Alliance would respond to any aggression quickly, and that all allies would respond forcefully to an armed attack. However, deterrence may still lack sufficient credibility given Russia’s and the Alliance’s respective force postures in the region.

Overall, Russia’s military forces would be at a distinct disadvantage in a protracted conflict with the United States and NATO. In the long term, with the requisite political will, the United States and NATO could leverage their advantages in military and economic power to prevail. Nevertheless, the reality remains that Russia’s force posture in North Central Europe, where current US and allied force posture is comparatively lacking, gives Russia a short-term advantage locally. A notable RAND study from 2016 underscored these challenges, concluding that a “force of about seven brigades, including three heavy armored brigades—adequately supported by airpower, land-based fires, and other enablers on the ground and ready to fight at the onset of hostilities” was needed to effectively defend the Baltic States.80David A. Shlapak and Michael Johnson, “Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank,” RAND, 2016, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1253.html.

Despite the important decisions and progress of allied leaders across the past three major summits—particularly Warsaw and Brussels, which addressed some of the weaknesses identified in the RAND report—a determined Russian conventional attack, especially if mounted with little warning, could still defeat current forward-deployed NATO forces in a relatively short period of time. For example, the often-cited nightmare scenario of a limited Russian land grab of territory in the Baltic States could take place well before US and allied reinforcements from Germany, Western Europe, or the continental United States could be brought to bear. Such a fait accompli could ultimately break the Alliance’s will and determination to live up to its Article 5 commitments. While the Baltic States present a different context than Russia’s last land grab in Crimea, and the likelihood of a Russian incursion into NATO territory is low, the United States and NATO must be prepared for any contingency. The United States and its allies can only do this through advance planning and preparation, including the deployment of the proper force mix in North Central Europe.

A first step must be to identify and rectify current gaps in the Alliance’s force posture in North Central Europe.

Gaps in the US and allied force posture