Introduction

Over the course of the last decade Russian foreign policy has taken critical turns, surprising not only the entire international community but also Russia’s own foreign policy experts. Arguably, the most notable turn came in March 2014 when Russia annexed the Crimean peninsula, setting in motion developments that are continuously shaping Russia, its neighbors, and, to a certain degree, global affairs. Clearly, Russia’s post-Crimean foreign policy does not exist in a vacuum. Its ramifications are colliding with regional and global trends that are effectively destabilizing the post-Cold War international order, creating uncertainties that are defining the contemporary international moment.

In this report, we deal with those whose job it is to explain the logic of Russia’s foreign policy turns and to analyze global trends and their meaning for Russia and the rest of the world. Although these experts, as a rule, do not directly influence political decision-making, their debates, as Graeme Herd argues, “set the parameters for foreign policy choices” and “shape elite and public perceptions of the international environment” in Russia.1Graeme Herd, “Security Strategy: Sovereign Democracy and Great Power Aspirations,” in The Politics of Security in Modern Russia, ed. Mark Galeotti (Surrey, England, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Pub. Co, 2010), 16. Especially in times of crisis and rapid change ideas produced at some earlier stage by experts and think tanks external to the state bureaucracy can suddenly obtain instrumental value and direct policy options.

In Part 1, we briefly discuss the role of think tanks in Russian foreign policymaking and present the landscape of Russian think tanks working on foreign policy issues. We distinguish among three basic institutional forms: academic and university-based think tanks, private think tanks, and state-sponsored think tanks. Highlighting the diversity of organizations, we then focus on four state-sponsored think tanks whose size, political contacts, and financial means allow them to dominate the think tank scene in Russia and that represent different ideological angles of a broad, yet also comparatively volatile mainstream: the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy (SVOP), the Valdai Discussion Club, the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC), and the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISI).

Part 2 follows this selection by looking at Russian foreign policy debates since 2014. We consider how experts writing for these four organizations have approached three major themes: the evolution of the concept of Greater Europe and European Union (EU)-Russia relations, the establishment of the Greater Eurasia narrative in the context of Russia’s declared pivot to the East, and the concepts of multipolarity and the liberal world order.

Table of Contents

- Think tanks and foreign policy making in Russia

- The landscape of Russian foreign policy think tanks

- The big four: State-sponsored think tanks in Russia

- Foreign policy narratives since 2014

- The end of Greater Europe

- Greater Eurasia or China’s junior partner?

- Multipolarity and world order

- Conclusion

Part One

Part Two

Part One

Chapter 1: Think tanks and foreign policy making in Russia

Any discussion of the role of think tanks in Russia needs to start with the fact that Russian foreign policymaking is highly centralized. According to the 1993 Constitution, the Russian president directs the state’s foreign policy.2Constitution of the Russian Federation, art. 86. Yet in the 1990s, the lower house of the Russian parliament, the State Duma, which had been dominated by the Communist Party in opposition to President Boris Yeltsin, at times exerted considerable influence on the course of events, for example by refusing to ratify international treaties or by developing independent policy proposals. In turn, Russia’s foreign policy goals had not yet been fixed and strategies remained subject to frequent changes and compromise.

Since the first election of Vladimir Putin to the presidency in March 2000, the policy process has been increasingly concentrated within the presidential administration, where Putin himself acts as the sole strategic decision maker. Starting in 2003, liberal oppositional parties were increasingly pushed out of the State Duma, and the new party of power, United Russia, received a constitutional majority. The remaining opposition parties, including the once highly critical Communists, were increasingly co-opted in support of presidential policies.

In consequence, today, direct personal access to members of the administration and/or the president is the only way to have any real influence on the course of political action. This dominance of the state bureaucracy and its insulation from societal forces shapes the environment for the development and activities of (foreign policy) think tanks, in a considerable departure from Western liberal democracies, where the think tank concept was first developed.

In the United States, think tanks have been traditionally understood as “nonprofit organizations” with “substantial organizational independence” and the aim to influence public policy making.3R. Kent Weaver, “The Changing World of Think Tanks.” PS: Political Science & Politics 22, no. 3 (1989): 563–78. In a path-breaking article thirty years ago, R. Kent Weaver suggested that such organizations come in three ideal-typical forms: “universities without students,” “contract research organizations,” and “advocacy think tanks.” His classification rests on the differences in staff, operational principles, and product lines. While “universities without students” and “contract research organizations” both value academic credentials and norms of objectivity, they produce different types of work: monographs and articles versus problem-focused analyses commissioned by state agencies. “Advocacy think tanks,” by contrast, recruit staff with various backgrounds, including from business, journalism, and the military, and often “put a distinctive spin on existing research” with the deliberate aim to influence policy making and public debate.4Ibid, 567.

This tripartite concept helps us make sense of different strategies within the marketplace of ideas, but the assumption of organizational independence from the state does not travel well beyond the Anglo-American tradition.5Diane Stone and Mark Garnett, “Introduction: think tanks, policy advice and governance” in Think tanks across nations: A comparative approach, ed. Diane Stone, Andrew Denham and Mark Garnett (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1998), 3. In continental Europe, think tanks, particularly those working on foreign policy issues, are often linked to state institutions and/or political parties. At the same time, they are actively engaged in policy development and enjoy considerable intellectual autonomy. By the same token, the notion of think tanks as exclusively nonprofits unnecessarily excludes organizations that exist as businesses but engage in public policy debates. This is problematic because, in some countries, including Russia, choosing enterprises instead of non-profit organizations as the legal form of choice for think tanks is simply a way to avoid increasing state control of politically active civil society and noncommercial activities.

Hence, rather than starting from a narrow definition of think tanks as a specific type of organization, we follow recent arguments that think tanks should be seen as “platforms, composed of many individuals who have multiple affiliations and multiple ideas.”6David Cadier and Monika Sus, “Think Tank Involvement in Foreign Policymaking in the Czech Republic and Poland,” International Spectator 52, no. 1 (2017): 119.

They often function as meeting places for key stakeholders to produce specific end-products, such as publications or events. As will become clear, such a flexible approach is especially helpful in Russia, where organizational boundaries can be fuzzy and where experts frequently collaborate and can belong to multiple think tanks. More important than establishing clear-cut boundaries is to investigate their historical trajectory, which includes different sets of practices and various forms of policy work.

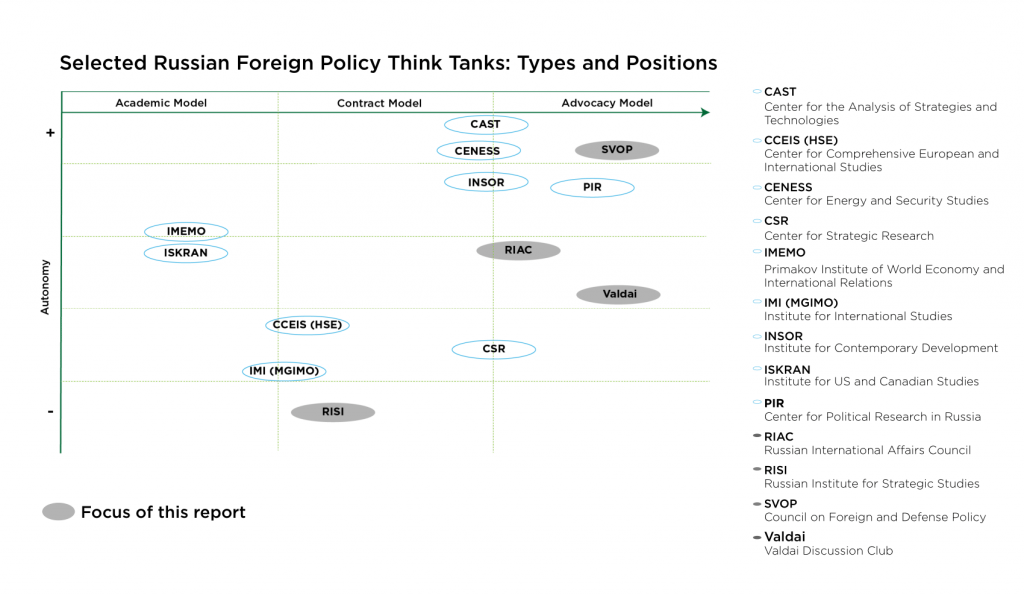

Different think tanks then can be usefully placed within a typological table along two dimensions: on the one hand, the kind and mixture of policy-related work following Weaver’s classification, differentiating among academic research, contract-based policy analyses, and advocacy; on the other hand, the degree of organizational autonomy, which includes institutional independence from both state agencies and private sponsors. The combination of both dimensions provides us with an admittedly rough, but helpful overview of the relative social position of thirteen selected Russian think tanks within the marketplace of producing policy ideas (Table 1).

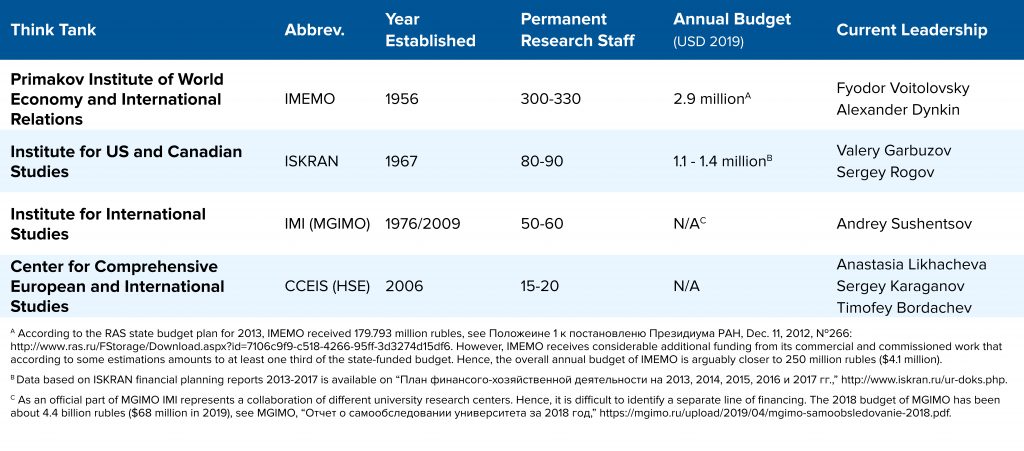

Our selection combines size, capacity, and institutional variety to illustrate the existence of different think tanks forms in Russia.7A dataset compiled by the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC 2015) presents ninety-four “organizations” active in the field of international research. However, the data collection among others includes eighteen institutions of the Russian Academy of Sciences, thirty university faculties, seven publications, three foreign organizations (including the Carnegie Moscow Center), and two polling firms. Moreover, since 2015 several centers listed in the directory have been dissolved or are inactive, while others focus dominantly on socio-economic policy issues. Hence, the actual number of Russian institutions in the field of foreign policy that could be categorized as think tanks broadly understood is considerably smaller and if one includes all area studies institutes of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) and certain universities closer to thirty. See http://ir.russiancouncil.ru/ir/. At the same time, the experts and think tanks discussed here do represent the dominant mainstream of the Russian foreign policy expert community with relevance for both policy and public debate. Think tanks beyond this selection usually (still) lack political relevance and critical mass,8For example, the Center for Strategic Assessment and Forecasts established by Sergey Grinyaev in February 2012 and the public diplomacy NGO Creative Diplomacy (PICREADI) founded in 2010 by Natalia Burlinova. study foreign policy only in passing,9For example, the Gorbachev Foundation, the Center for Political Technologies (founded in 1991 by Igor Bunin), the Institute of Political Studies (established in 1996 by Sergey Markov) and the Sulashkin Center (established by former Duma deputy Stepan Sulashkin in 2013). or focus on concrete world regions with a dominant domestic policy perspective.10 This includes, for example, the Institute of the Middle East established as the Institute of Israel in 1993 by Yevgeny Satanovsky. Moreover, the area studies institutes of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS), i.e. the Institute of Europe, the Institute of Oriental Studies and the Institute for African Studies, cover an entire range of issues from language, to history and politics. A special case are those centers that work among others on the post-Soviet space and specifically Ukraine, enjoying close personal relations with political power such as the Institute of CIS countries founded in 1996 by SVOP member and Duma deputy Konstantin Zatulin and the Center for Current Policy, established in 1992 and currently led by former deputy head of internal policy at the Presidential Administration, Alexey Chesnakov who is close to Presidential aide Vladislav Surkov. Finally, some think tanks that have been active in the past have either been shut down or reduced their activities to a minimum.11For example, the Institute for Political and Military Analysis (Alexander Sharavin and Alexander Khramchikhin; reduced activities), the Center for Strategic Assessments (Sergey Oznobishchev and Alexey Konovalov; inactive), the Institute of Strategic Studies and Analysis (Vagif Guseynov; dissolved after 2014) and the monarchist-orthodox ‘analytical center’ Katekhon, which ceased its public activities in Spring 2017. In this context it is important to emphasize that most Russian (foreign policy) think tanks are very small and depend on the leadership and engagement of just one or two persons. Hence, think tanks are usually heavily interrelated on an interpersonal level with individual analysts working simultaneously for several institutions. Because foreign policy is not a professionally clear-cut field of knowledge production, there are also overlaps with institutions dealing dominantly with economic and military policy issues.12In the field of military analysis there exists many different networks and clubs led by former officers, including for example the Academy of Military Sciences (Makhmut Gareev), the Academy of Geopolitical Problems (Leonid Ivashov), the Club of Military Leaders (Anatoly Kulikov) and the Association of Military Political Scientists (Vasily Belozyorov). With the exception of the Academy of Military Science most of them, however, do not issue policy analyses or (academic) research products on any significant scale.

The following two parts describe the emergence and main attributes of these thirteen think tanks, which are denoted by their official acronyms. First, we provide an overview of the general landscape of Russian foreign policy think tanks, which we divide into three groups: academic and university-based think tanks, private think tanks, and state-sponsored think tanks. Second, within the last group we zoom in on four organizations (in gray) that have played a significant role in Russian foreign policy debates in the last decade yet simultaneously represent different ideological angles. The more detailed information about their institutional design and historical trajectory will help us understand the social context of the policy debates that will be at the center of Part 2.

Chapter 2: The landscape of Russian foreign policy think tanks

Russian think tanks working on foreign policy issues can be divided into three basic groups depending on type of ownership and how they evolved historically. First, there are academic state-funded institutions, which include research institutes within the system of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) and state universities with faculties focused on studying foreign policy and international relations. Second, the collapse of the Soviet Union enabled not only former scholars but also journalists and military officers to establish their own private think tanks, particularly in the 1990s. Although many folded over time, some are still operating in distinct niches despite increasing political pressure. Finally, since the late 2000s the Russian state, with its growing political ambitions and economic potential, has actively invested in the creation of (foreign policy) think tanks and intellectual platforms. Nevertheless, as we will argue, the source of this support has been neither monolithic nor unambiguous. Rather, state-sponsored think tanks represent, to some extent, different positions and power struggles within the political elite.

Given this institutional diversity, Russian think tanks exist in numerous legal forms. Apart from those organizations which are part of state universities or exist as “state budget scientific institutions,” most (foreign policy) think tanks come in the form of either (autonomous) non-commercial organizations (NCO) or enterprises. Whereas the latter provides more liberty of action, the former is more common, even among state-sponsored think tanks, despite increasing regulation. In contrast to the United States, where think tanks as non-profit organizations and their donors enjoy significant tax advantages, the Russian tax law knows such privileges only for socially oriented NCOs, but on a lower scale.13Some NCOs, such as non-commercial partnerships, are allowed to engage in business activities. A heavy blow for think tanks existing as NCOs has been the revision of the Russian NCO law from July 2012, introducing the status of “foreign agents” for those NCOs that in some form touch upon political issues in their work and receive foreign funding.14Federal law “On non-commercial organizations,” Art. 2 (6), see http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_8824/87a16eb8a9431fff64d0d78eb84f86accc003448/ Currently there are seventy-five such organizations, which are subject to intensified bureaucratic control and often public harassment. Moreover, since May 2015, the law on undesirable organizations has terminated the activities of several foreign donor organizations of Russian politically active NCOs, including the Open Society Foundation, the German Marshall Fund, and the MacArthur Foundation.15The current list of undesirable organization whose activities are banned includes fifteen institutions, see https://minjust.ru/ru/activity/nko/unwanted. The MacArthur Foundation decided to leave Russia after the law had been adopted, see https://www.macfound.org/press/press-releases/statement-macarthur-president-julia-stasch-foundations-russia-office/.

Academic and University-Based Think Tanks

Most institutions doing academic research on foreign affairs and international relations in Russia are part of the Academy of Sciences and represent area studies institutes, which were predominantly founded in the late 1950s and 1960s to support Soviet international engagement. Given the lack of professional experience with many world regions inside the state bureaucracy at the time, these institutes became centers of nonmilitary knowledge production on the culture, politics, and economies of various countries, including the United States.16In addition, there are the Institute for African Studies (1959), the Institute for Latin America (1961), the Institute of the Far East (1966), and the Institute of Europe (1987). Together with the Economic Research Institute (1976) and the Institute of History, Archaeology, and Ethnography of the Peoples of the Far-East (1971), which both belong to the Far Eastern Branch of the RAS, since 2010 they constitute the department on global problems and international relations. In Soviet times, the two best-known were the Institute for US and Canadian Studies (ISKAN, today known as ISKRAN) founded in 1967 and the Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) that had been re-established in 1956.17IMEMO became the successor to the Institute for World Economy and World Politics, which had been established in 1925. In 1947, however, it was abolished after the ideas of its long-term director, Eugene Varga, about the postwar posture of the Soviet Union came into conflict with Stalin’s policies. Both profited from the Western focus of Soviet foreign policy, large research staffs, and their directors’ political connections.18For example, after Mikhail Gorbachev became general secretary of the Communist Party in March 1985, he appointed his friend, long-term ambassador to Canada and former IMEMO Director Alexander Yakovlev, to secretary of the Central Committee in charge of ideology. Yakovlev’s successor at IMEMO, Yevgeny Primakov, joined Soviet politics in 1989 as the chairman of the Soviet of the Union, the lower house of the Soviet parliament. The time of perestroika and glasnost was the heyday for these Soviet think tanks’ involvement in politics. Several initiatives by the political leadership were rooted in ideas developed at IMEMO and ISKAN or had been directly suggested by them. For the political role played by these institutes and their experts in the Soviet Union, see Jeffrey T. Checkel, Ideas and International Political Change: Soviet/Russian Behavior and the End of the Cold War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997) and Robert D. English, Russia and the Idea of the West: Gorbachev, Intellectuals, and the End of the Cold War (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000).

Today, the dominant university remains the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO), which is directly subordinate to the Russian Foreign Ministry.”

This photo was taken at the first session of the International Scientific and Expert Forum “Primakov Readings” titled “Is Russia and the US a limited confrontation or a potential partnership?” on June 29, 2017. Source: Wikimedia Commons/IMEMO RAS

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the institutionalized system of policy advisory based on the Communist Party structure dissolved. The fully state-financed institutes lost much of their funding and given the economic crisis, state interest in foreign and security policy issues diminished. In addition, many scholars, particularly young ones, got better-paid jobs in business or left the country altogether.19For example, in 1986, IMEMO had more than 700 researchers and almost 1,000 employees. With currently about 350 employees, it is again at the level of the late 1950s but remains by far the largest institute within the RAS department on global problems and international relations. See Pyotr Cherkasov, ИМЭМО Очерк истории (Moscow: Весь Мир, 2016), 428, 741. In consequence, the average age of Russian scholars steadily increased, whereas Western approaches–particularly International Relations (IR) theory—which had not officially existed as a subject in the Soviet Union—had to be learned anew. Only in the mid-2000s did some of the institutes and Russian academia in general partially recover from financial and institutional decay.20In the context of the RAS reform from 2013 to 2018 the maximum age for directors of state research organizations was set at 70. See “Федеральный закон от 22 декабря 2014 г. N 443 Ф3,” https://rg.ru/2014/12/26/fz443.dok.html. The different institutes, however, have had vastly different levels of success, depending on their leadership. For example, while IMEMO under the directorship of Alexander Dynkin (2006-2016), who now acts as the institute’s President and head of academic research, has secured new private funds, attracted young scholars, and once again become an international household name, not least through events such as the annual Primakov Readings, the once-prominent ISKAN (ISKRAN) has faced financial difficulties and overall decline. In July 2015, IMEMO was named after its former director and late Russian prime minister, Yevgeny Primakov, who had passed the month before.21“ИМЭМО РАН ходатайствовал о присвоении институту имени Примакова,” Interfax, July 3, 2015, https://www.interfax.ru/russia/451424.

Traditionally, the Soviet model envisaged a split between research done at the RAS institutes and teaching as the exclusive responsibility of universities. After 1991, this division of tasks started to break down, and Russian universities increasingly moved into applied research on foreign policy and international affairs. Today, the dominant university remains the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO), which is directly subordinate to the Russian Foreign Ministry. Together with the Diplomatic Academy, it is responsible for the education of most Russian diplomats.

However, as the think tank of the Foreign Ministry, MGIMO is also deeply involved in applied policy work and produces research notes and reports for government agencies. In 1976, the Institute established the Problem Research Laboratory for System Analysis, which eventually became one of just two Soviet centers studying IR theory.22Mark Khrustalyov, “Две ветви ТМО в России,” Международные процессы 4, ном. 2 (2006), 119-128, http://intertrends.ru/system/Doc/ArticlePdf/1058/PERSONA-GRATA-11.pdf After several reforms, in 2009 the lab became the Institute for International Studies (IMI), which consists of ten research centers that loosely cooperate. Together, they are responsible for executing the annual Russian Ministry of Forign Affairs (MFA) policy research agenda and answering ad-hoc inquires of the Ministry. Since October 2018, IMI has been headed by the young US specialist Andrey Sushentsov, who is also program director at Valdai and in 2014 founded his own small analytical agency (“Foreign Policy”).23Analysts writing for the agency are predominantly based in Russian universities, particularly MGIMO. The agency is available at http://www.foreignpolicy.ru/. Since 2017, Sushentsov has been the president of another MGIMO in-house analytical center called “Eurasian Strategies” with largely the same people involved, see http://eurasian-strategies.com/about-us/leadership/.

Moreover, in the post-Soviet era, the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE) in Moscow has become a hub for modern social science research. In 2006, it established a faculty on the global economy and international affairs under the leadership of then-SVOP Chairman Sergey Karaganov. While the faculty and the entire university could be legitimately seen as think tanks in their own right, Karaganov established the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies (CCEIS) in October 2006 as a specialized center with seven initial employees, including his associates Timofey Bordachev and Dmitry Suslov, who at first became managing director and deputy managing director, respectively.24Bordachev is now scientific supervisor (as is Karaganov), whereas Suslov remains deputy academic director. Director Anastasia Likhacheva has led CCEIS since spring 2019.

From the start, CCEIS had been envisaged as the leading policy research center of the faculty, providing commissioned reports to Russian enterprises and different economic-related state institutions with a focus on EU-Russian relations and the institutional development of the EU. Over time, it widened its research activities and increasingly started to promote the study of Eurasia, the Far East, and international cooperation within the framework of the association of five major emerging national economies known as the “BRICS.” Although applied research on the EU continued, the focus after the Russian-Georgian war in 2008 shifted to a more critical and confrontational attitude toward EU-Russia cooperation. This shift eventually resulted in the development of the “Greater Eurasia” paradigm as an alternative to both “Wider Europe” promoted by the EU and “Greater Europe,” the preferred concept of the Russian leadership in the early 2000s.

Private Think Tanks

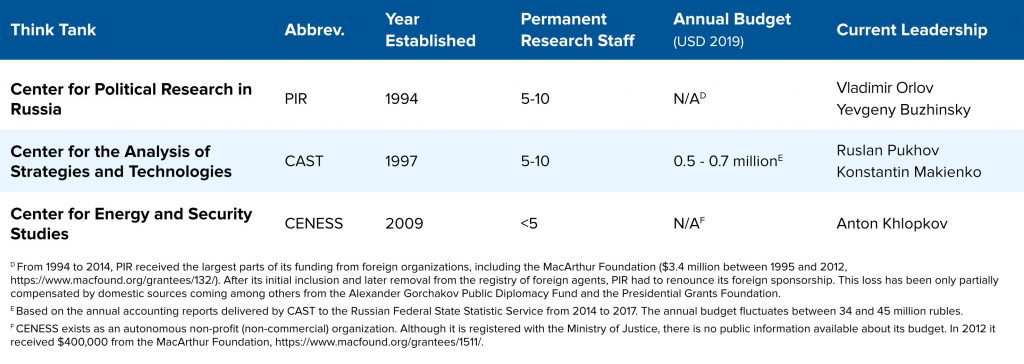

The collapse of the Soviet Union enabled private think tank initiatives for the first time. Several former academics from the RAS institutes and state universities established their own small policy research centers and networks. Given the lack of domestic funding, almost all had to rely on Western sponsorship. Many remained one-person operations and were soon dissolved. On the other hand, the economic crisis in Russia during the 1990s did not particularly encourage research on foreign and security policy beyond nuclear nonproliferation and arms control. State demand existed, if at all, for economic and financial policy issues. Nevertheless, during this time several successful private initiatives evolved as enterprises or noncommercial organizations. Since 2012, the noncommercial groups have faced considerable challenges due to changing legislation—particularly the foreign agents law from June 2012 and the law on undesirable organizations from May 2015—that made it more difficult to attract sponsorship from abroad.

Two successful private think tanks are the Center for Political Research in Russia (PIR) and the Center for the Analysis of Strategies and Technologies (CAST). The first was established by journalist Vladimir Orlov and some friends in spring 1994 at the newspaper Moskovskie Novosti (Moscow News), which had been the mouthpiece of Soviet perestroika. They set up the journal Yaderny Kontrol (Nuclear Control)25In 2007 the journal was renamed Indeks bezopasnosti (Security Index). The journal ceased to exist in 2016, See also Vladimir Orlov, “Brave New PIR: Turning the 20-year Journey into Generation 2.0,” Security Index 20, no. 3-4 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1080/19934270.2014.986364. in both English and Russian and soon received funding from the MacArthur Foundation and political-institutional support from MGIMO Rector Anatoly Torkunov and Yeltsin’s National Security Aide Yuri Baturin. Subsequent increases in funding enabled PIR to expand its work to new areas. Moving away from the narrow focus on nuclear nonproliferation, it launched projects on chemical weapons, missile technology, nonproliferation, military and technical cooperation, and civilian control of military activities. PIR, thus, transformed into what Orlov terms a “boutique think tank”26Ibid., 5. and became a hub for ambitious young students and researchers.

CAST was founded in 1997 by two former PIR employees, Ruslan Pukhov and Konstantin Makienko, who took with them the bulletin on conventional arms they had produced for PIR. In contrast to PIR, which remains a noncommercial organization, CAST largely survives by selling subscriptions to its Eksport Vooruzhenii (Arms Export) journal to a national and international audience and by producing analyses for Russian businesses active in the military-industrial complex. In addition, since 2008, CAST has published several monographs and edited volumes on topics including the 2008 Georgia-Russia conflict, Russian army reform, the Chinese defense industry, military aspects of the Ukrainian crisis, and Russia’s military engagement in Syria.

Finally, another think tank at the intersection of

foreign policy and technology is the Center for Energy and Security Studies

(CENESS), established in 2009 to focus on nuclear energy issues. Although it is

the smallest of the organizations discussed here, with fewer than five permanent

staff members, its founder, Anton Khlopkov—another PIR alumnus—has developed

close ties with stakeholders in the Russian nuclear industry and relevant

ministries, where his expertise as a physicist and knowledge about Iran’s

nuclear program is highly valued. Since 2010, CENESS has organized the Moscow

Non-Nonproliferation Conference, which takes place every other year and usually

attracts more than 200 high-ranking Russian and international participants as

well as sponsorship from various western embassies.

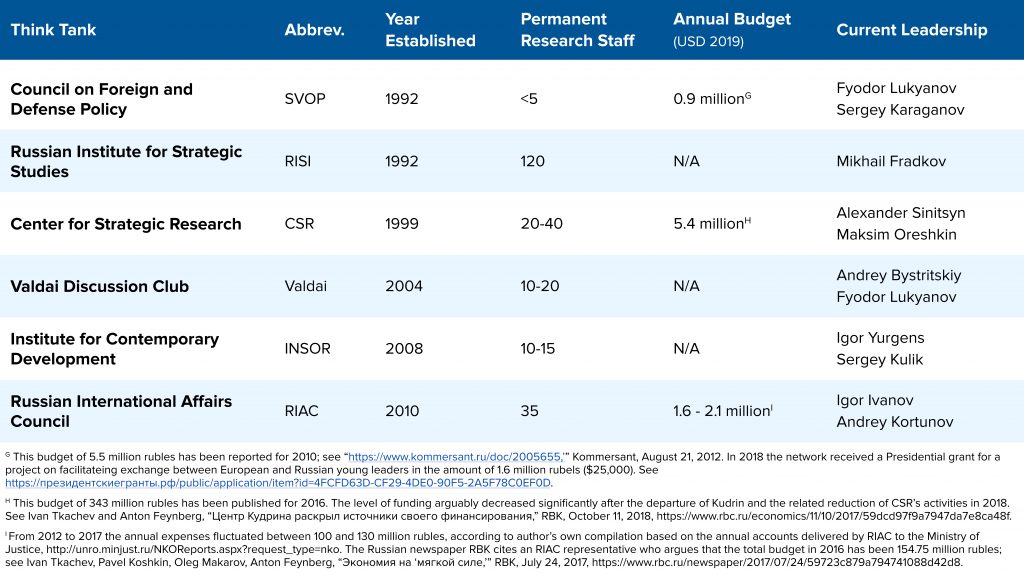

State-Sponsored Think Tanks

Since the late 2000s, as the Kremlin’s coffers have grown and officials have sought to promote Russian soft power globally, the Russian government has systematically sponsored official foreign policy think tanks and the consolidation of the Russian expert community. Organizations sponsored by the political elite are, as a rule, significantly larger than private think tanks and cover a broad spectrum of policy issues. Sponsorship as we use the term here, however, does not necessarily equal direct financing as in the case of the academic institutes of the RAS. Due to the importance of informal political practices in Russia, material and symbolic support can be secured by unofficial relations with major enterprises and political stakeholders. Moreover, fruitful interaction with state officials presupposes a certain level of moderation, which excludes extreme policy positions that reject the political regime as such. At the same time, the lack of strong political institutions beyond the Russian presidency makes the course of political action more volatile, with some think tanks, such as the Center for Strategic Research (CSR) and the Institute of Contemporary Development (INSOR), enduring steep up-and-down cycles.

CSR was established during Putin’s first presidential campaign in winter 1999 with the aim to develop a long-term program on social-economic issues (Strategy-2010). Since then, it has given an institutional platform to the Russian government’s leading economics personnel, most of whom came with Putin from St. Petersburg. To some extent, it is the think tank of the Ministry of Economic Development. The pace of CSR’s activities has fluctuated considerably depending on the Kremlin’s political interest. In 2011-2012, economic experts associated with CSR took part in elaborating the follow-up Strategy-2020 and warned against social unrest, before the think tank’s importance in federal politics diminished with the nationalist turn in Russian politics after Putin’s reelection in March 2012.

However, with the return of former Russian Finance Minister Alexey Kudrin, who in April 2016 agreed to prepare a new strategy for Russia’s socioeconomic development until 2024, CSR once again flourished. With Kudrin as director, the think tank for more than a year became the central Russian expert platform, with various working groups and more than 1,000 contributing researchers from different institutions.27RTVi, “Игорь Юргенс: ‘От президента сейчас зависит больше, чем от Политбюро во времена СССР,’” YouTube video, 56:49, November 25, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_81WN5uVyiw. Although its focus remained on economic and financial issues, CSR also, for the first time, took on “external challenges and security,” for which then-IMEMO Director Alexander Dynkin had lobbied. Kudrin and Dynkin were convinced that without a normalization in relations with the West, the 3 percent growth target, set by CSR as the overall goal, was impossible. A working group led by IMEMO researcher Sergey Utkin prepared several reports, including theses on Russia’s foreign policy and the country’s global positioning for 2017 to 2024. Yet after submitting the main report to Putin in May 2017 and Kudrin’s appointment to lead the Russian Accounts Chamber, CSR once again pared back its activities and Utkin’s working group was dissolved.

INSOR has also seen its fortunes wax and wane. Established as a noncommercial foundation out of the Center for the Development of an Information Society (RIO) in March 2008, INSOR also touches upon foreign policy issues, mainly through the prism of economic development and modernization. Politically sponsored by then-Minister of Communications and Information Technologies28From May 2008 to September 2010, Reyman was an advisor to President Medvedev. Today, he is the director of the Alternativa Capital investment fund. Leonid Reyman, Director Igor Yurgens in 2006 started to advance proposals for Russia’s long-term socioeconomic modernization as possible successor strategies for the original CSR program from 2000.

In the contest between Defense Minister Sergey Ivanov and first Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev to follow Putin as president, INSOR sided with Medvedev, who tasked the institute with developing national projects. Medvedev’s eventual victory in the internal power play allowed Yurgens to proceed with his projects and RIO transformed into INSOR as the new presidential think tank. At INSOR’s opening ceremony in March 2008, the president argued that “the authorities do not need compliments or flattery from the expert community, they need public and comprehensive discussion.”29Oleg Shchedrov, “Russia’s Medvedev urges social, economic debate,” Reuters, March 18, 2008, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-medvedevexperts/russias-medvedev-urges-social-economic-debate-idUSL1880846820080318. Although Medvedev joined INSOR as the head of the board of trustees, the Institute received no financial support from the state budget.

Over the course of Medvedev’s presidency, INSOR became an intellectual platform for the collaboration of experts from universities and research centers, supporting the declared socioeconomic modernization agenda. The ability of INSOR to promote these ideas politically depended, however, entirely on Medvedev’s position and personal fate. The failing bet for his reelection in September 2011 and Putin’s return to the presidency put an end to INSOR’s special position and modernization strategy. As Yurgens put it at the time, “We lost to the ‘preservers’ [okhraniteli]. They just beat us.”30Igor Yurgens, “Мы проиграли охранителям,” The New Times, March 3, 2012, https://newtimes.ru/articles/detail/50506.

The next section presents the historical development

and current position of four state-sponsored think tanks in more detail:

Council on Foreign and Defense Policy (SVOP), Valdai Discussion Club, Russian

International Affairs Council (RIAC), and Russian Institute for Strategic

Studies (RISI). Although these organizations differ significantly in

institutional design and historical origins (Table 3), they all represent the

very broad Russian mainstream—they are either personally and/or intellectually

close to state institutions. This similarity allows us to compare their output,

arguing that even in Russia, state owner- and sponsorship does not necessarily squelch

critical engagement. In fact, as we show in Part 2 of this report, these four

organizations take quite different political positions.

Chapter 3: The big four: State-sponsored think tanks in Russia

The Council on Foreign and Defense Policy (SVOP)

Among state-sponsored think tanks, SVOP is the exception to the rule. As one of the oldest Russian nongovernmental organizations, it does not receive financial support from the state but survives on private and commercial donations. Yet SVOP receives symbolic and intellectual state sponsorship, insofar as several members enjoy close relations with political power. In addition, SVOP is not a compact institute, but a network of private citizens with varying professions and political views. SVOP’s roughly 200 members include many leading figures of other think tanks and academics, but also journalists; entrepreneurs; scholars; politicians; and diplomats, such as Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and several of his deputies; Dmitry Rogozin, the director general of the Russian state space agency, Roscosmos; and former deputy prime minister.

The transformation of RIA Novosti to Rossiya Segodnya and the replacement of Mironyuk with Kiselyov, whose views on media and state propaganda differed considerably from the progressive bureaucrat’s, led to Valdai’s reorganization.”

Sergei Karaganov (center-left), Sergei Lavrov (center-right), and Fyodor Lukyanov (right) at an SVOP panel in Moscow on April 8, 2017. Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs

The initiative to establish SVOP emerged in the wake of the failed coup d’état in the Soviet Union in August 1991. Karaganov, at the time deputy director of the Institute of Europe in the Soviet Academy of Sciences, proposed to Vladimir Rubanov, Vitaly Shlykov, and Alexander Zalko that they assemble a group of people in order to save the collapsing country and to provide a platform for integrating various elite members, particularly those in the security services. Unlike the scholar Karaganov, the other three had had long careers in the Soviet military and intelligence and turned to politics under Gorbachev.

In January 1992, this initial group was joined by a dozen men for the constitutive conference at the Institute of Europe. Coming predominantly from the academy or military, most of them had begun to build political careers, including, for example, Vladimir Lukin, a former ISKAN scholar who would become Russia’s ambassador to the United States, a member of parliament, and human rights ombudsman under Putin. From that time on, the group would meet once a year at a resort on the outskirts of Moscow.

Soon, SVOP established several working groups on pressing issues and organized bilateral and international conferences with partners in the United States, Ukraine, and Germany, among others. In the 1990s, the network created a stir by publishing broad strategies for the development of Russian foreign and security policy that were critical of the Yeltsin Administration’s policies. SVOP members initiated and promoted important debates on, for example, widespread drug abuse in Russia and its health consequences, the urgent need for reform of the Russian military, and the political union with Belarus. While driving important debates, however, it remains unclear whether SVOP persuaded the government to adopt specific policies.

Nevertheless, a growing number of SVOP members did move into important political positions, particularly after Yeltsin’s reelection in 1996. With the appointment of SVOP member Yevgeny Primakov, first as foreign minister in January 1996 and then as prime minister from September 1998 to August 1999, SVOP enjoyed its political heyday. Despite some differences, most members supported Primakov’s agenda, consisting of demanding respect for Russian national interests, a multi-vector foreign policy, and support for multipolarity as the desired principle of international order.

Yet Primakov’s bid for the presidency failed after losing elections to the State Duma in winter 1999 (a campaign that had been openly opposed by Russian oligarchs) and that put an end to the political advancement of SVOP members. Instead, Putin’s election brought in new elites from St. Petersburg, and the old guard from the late-Soviet and Yeltsin eras slowly but steadily lost influence and position.

The club’s focus shifted from informing foreigners about Russian politics to promoting distinct Russian views on international affairs.”

President Vladimir Putin’s speech at the final session of the seventh meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club in Sochi, Russia on October 22, 2015. Source: Kremlin.ru

Hence, since the 2000s, SVOP has seemed less like a political club influencing decision making and more like a platform for public advocacy and education, particularly starting with the publication of the journal Russia in Global Affairs in 2003. Fyodor Lukyanov, who in 2012 took over the chairmanship from Sergey Karaganov, says SVOP performs “enlightenment functions.”31Fyodor Lukyanov, “Об ирландских монахах или роль независимых экспертных центров и СМИ в российской внешнеполитической дискуссии,” Indeks Bezopasnosti 1, ном. 112 (2015), 90, http://pircenter.org/media/content/files/13/14301348380.pdf. Since 2013, it has conducted public lectures and in 2016 it established a policy analysis and writing seminar series over several months for aspiring young experts. Although SVOP members continue to meet regularly and publish political strategies, the organization has lost its former institutional connection to real power, aside from the continuing membership of Lavrov and his deputies.

Valdai Discussion Club

Thanks to its annual meetings with Vladimir Putin, the Valdai Discussion Club is arguably Russia’s best-known intellectual brand in international think-tankery. Valdai is formally independent and does not receive direct financial support from the government. Yet the commingling of politics and business in Russia ensures that funding comes from state-owned and large private companies, directly coordinated by the presidential administration. Although the amount of that financial support is kept under wraps, Valdai’s current business partners include the Metalloinvest mining company, owned by Alisher Usmanov; Alfa Bank Group—Russia’s largest private bank—headed by Petr Aven and Mikhail Friedman; and the VTB Group.

The Valdai Discussion Club originally emerged from the international conference “Russia at the Turn of the Century: Hopes and Realities,” organized in September 2004 by SVOP and the Russian state news agency RIA Novosti in Veliky Novgorod, near Lake Valdai.32Fyodor Lukyanov, “Вечные ценности автаркии,” Gazeta.ru, September 9, 2004, https://www.gazeta.ru/comments/2004/09/08_a_168862.shtml. The event was the brainchild of Svetlana Mironyuk, then editor in chief at RIA Novosti, but Karaganov, at the time SVOP chairman (and now honorary chairman), and his team actively engaged in its intellectual conceptualization. The conference culminated in a meeting of thirty-nine participants from Germany, France, and the United Kingdom with Putin at his state residence in Novo-Ogaryovo. In the following years, Valdai increasingly institutionalized, and annual meetings were held in several Russian regional cities, while the core concept and the number of participants remained stable.

That changed after 2009, when the club began to supplement its annual autumn meetings with international events on Russian politics and international relations in cooperation with foreign partners. For example, in 2009 Valdai hosted conferences in London and Amman, and in 2010 events were organized in Berlin, Shanghai, Beijing, and Valletta. Working groups on the future of US-Russia relations were held at Harvard University and in Moscow and Boston, and were co-sponsored by various US foundations, including the Carnegie Corporation, the Open Society Foundation, and the MacArthur Foundation. Despite the presidential administration’s informal support of Valdai, the change in political winds after Putin’s reelection in March 2012 buffeted the organization. In December 2013, Valdai’s co-founder, Mironyuk, was abruptly fired from RIA Novosti, which itself was abolished by presidential decree to make way for the Rossiya Segodnya state news agency Segodnya under the leadership of Dmitry Kiselyov.33Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 09.12.2013 г. № 894, “О некоторых мерах по повышению эффективности деятельности государственных средств массовой информации,” http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/37871. Two years earlier, the presidential administration had objected when Mironyuk began her Master of Business Administration (MBA) studies at the University of Chicago. She said she was advised that a Russian state media administrator of her seniority should not travel to the United States to receive an education.34Yulia Taratuta, “Светлана Миронюк: ‘Я точно знаю, что никогда больше не буду работать на государство,’” Forbes, October 30, 2015, http://www.forbes.ru/forbes-woman/karera/304331-svetlana-mironyuk-ya-tochno-znayu-chto-nikogda-bolshe-ne-budu-rabotat-na. After that, she clashed repeatedly with Mikhail Lesin, a Putin aide,35Lesin was found dead in a DC hotel room in November 2015 under suspicious circumstances. and Alexey Gromov, first deputy chief of staff of the presidential administration, about the role and purpose of state media.36Taratuta, “Светлана Миронюк.” The transformation of RIA Novosti to Rossiya Segodnya and the replacement of Mironyuk with Kiselyov, whose views on media and state propaganda differed considerably from the progressive bureaucrat’s, led to Valdai’s reorganization. The club decided to split from RIA Novosti. Instead, RIAC, the Higher School of Economics (HSE), and MGIMO were brought in as new partners. The Foundation for Development and Support of the Valdai Discussion Club, which had been established in March 2011, subsequently took over management of the club’s projects. In parallel, Valdai’s organizational procedures and agenda were reformed. What had, according to one Valdai expert, been a “tourist office with an intellectual-propagandist odor”37Interview with one Valdai expert. turned increasingly into an analytical center.38Sergei Podosenov, “Валдайский клуб ждет перестройки,” Gazeta.ru, July 21, 2014, https://www.gazeta.ru/politics/2014/07/18_a_6118873.shtml.

The club’s focus shifted from informing foreigners about Russian politics to promoting distinct Russian views on international affairs. Accordingly, Valdai established five annually rotating policy programs, each led by a representative of a participating organization. Sushentsov, director of the Institute of International Studies at MGIMO since October 2018, became responsible for the study of war and armed conflict. Dmitry Suslov, a former journalist from St. Petersburg and Karaganov’s associate at HSE, focuses on regionalization and US-Russia relations. Timofey Bordachev, who heads the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies at HSE, has been curating the program on Eurasia since 2015. Ivan Timofeev, program director at RIAC, and MGIMO professor Oleg Barabanov are responsible for topics including social stability and the transformation of global institutions. Finally, SVOP Chairman Lukyanov functions as Valdai’s research director.

The 2014 relaunch also widened Valdai’s publication activities and multiplied its outreach platforms. Bimonthly reports that had been published since winter 2009 became more frequent and comprehensive. Since October 2014, the organization has also been publishing short analytical articles, the so-called “Valdai Papers,” by Russian and international experts.39“Valdai Papers,” Valdai Discussion Club, accessed May 10, 2019, http://valdaiclub.com/a/valdai-papers. Short video interviews with conference participants also were introduced as a new multimedia format. In addition, the number of participants at the annual meetings of the Valdai Discussion Club and the scale of the event itself have steadily increased. At its 10th anniversary in September 2013, almost 200 Russian and international experts participated,40“Ежегодные заседания дискуссионного клуба ‘Валдай,’” RIA Novosti, October 15, 2018, https://ria.ru/20181015/1530522198.html. and after changing venues for several years, the annual Valdai conference has been organized in Sochi since 2014.

Russian International Affairs Council

In February 2010, President Medvedev issued an order establishing RIAC as a noncommercial partnership under the patronage of the Foreign and Education ministries. It took the Foreign Ministry, however, more than a year to complete the necessary procedures and establish the legal basis for providing state funding for daily operations. RIAC is part of a larger effort to improve Russia’s image abroad and promote Russian perspectives internationally.

Although it is difficult to establish a direct causal relationship, some of the organizations in the report were made to register as foreign agents, forced to reduce their activities, or even dissolved.”

RIAC President Igor Ivanov (left) and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (right) at the annual general meeting of the Russian Council for International Affairs (INF) on November 20, 2018. Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs

At the second annual meeting in 2011, RIAC President and former Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov said, “The council has been created as an instrument to unite the Russian foreign policy community, and not as a bureaucratic structure or an alternative to one or another existing organization.”41Vladislav Vorobyov, “У дипломатов появился новый инструмент,” Rossijskaya Gazeta, no. 157 (5533), July 21, 2011, https://rg.ru/2011/07/21/rsmd.html. Ivanov said Foreign Ministry expertise, although considerable, could not by itself forecast complex developments in international relations, such as the Arab Spring. That kind of prescience would require scientific know-how, permanent monitoring, consultations with international experts, and regular contact with a wide range of societal groups. Hence, RIAC was established as a platform rather than an analytical center, and, in the words of Council’s Director of Programs Ivan Timofeev, compares with the Council on Foreign Relations in the United States or the German Council on Foreign Relations.42Ivan Timofeev, “Советы по международным делам: зарубежный опыт и российский проект,” Международная жизнь (January 2012), 15-20. As such, it has a small in-house staff of around thirty-five, who in 2011/2012 were predominantly recruited directly from university, first as interns and later as project managers.

The expert work, by contrast, builds upon various forms of cooperation with established research institutions, including the institutes of the RAS and individual researchers. Major events are organized by reaching out to RIAC’s extensive membership base of individuals and corporations, which include, for example, the Alfa Bank Group, the state technology corporation Rostec, and energy companies such as Lukoil and Transneft. Together, they unite representatives of Russian academy, business, diplomacy, and politics. RIAC’s individual memberships have doubled from about eighty in 2011 to more than 160 today.

Despite its diversity, RIAC’s membership base is ideologically centrist. Representatives of the extreme right or left who, at some point, were prominent political commentators, such as extreme right-wing neo-Eurasianist Aleksandr Dugin and left-wing nationalist Sergey Kurginyan, neither belong to nor collaborate with the organization. Consequently, although RIAC represents a broad spectrum of social and intellectual positions, it constitutes the mainstream of the Russian foreign policy expert community, as it is dominated by Foreign Ministry officials and RAS academics. The integrating figure of both professional spheres remains the well-respected Ivanov.43Aside from his political standing that partially stems from his close relationship with Primakov, who he had known since their days at IMEMO in the early 1970s, RAS scholars emphasize Ivanov’s academic credentials and interest in research. See Vladimir Kara-Murza, “Александр Шаравин об отставке Игоря Иванова,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, July 9, 2007, https://www.svoboda.org/a/401773.html.

With this prominent support and its wide social network, RIAC has become the main communication platform for Russian foreign policy experts. To some extent, it plays the role SVOP did in the 1990s, at least in strategic coordination, debate, and international outreach, though on a different scale. Unlike SVOP, RIAC is primarily financed by the state budget via the Foreign Ministry. In the first three years of operation from 2012 to 2014, almost all its spending—more than 95 percent—came from the state budget, including the federal, regional, and municipal levels. Since 2015, the share of donations from Russian businesses and private citizens, as well as RIAC’s own commercial activities, in its annual expenses has been increasing, and in 2017 accounted for almost one third.44Own compilation based on the annual accounts delivered by RIAC to the Ministry of Justice,

http://unro.minjust.ru/NKOReports.aspx?request_type=nko. However, officially declared expenses suggest that, in absolute terms, annual state funding has been rather stable over time.45Based on the annual accounts delivered by RIAC to the Ministry of Justice expenses coming from the state budget fluctuated between 98 and 110 million rubles from 2012 to 2016. In 2017 they decreased to 83 million rubles, but in 2018 again accounted for 92 million rubles. By contrast, the Russian newspaper RBK argues that absolute state funding has been constantly decreasing from 100 million rubles in 2014 to merely 79.67 million rubles in 2018, Ivan Tkachev, Pavel Koshkin, Oleg Makarov, Anton Feynberg, “Экономия на ‘мягкой силе,’” RBK, July 24, 2017, https://www.rbc.ru/newspaper/2017/07/24/59723c879a794741088d42d8.

In April 2016, RIAC leadership teamed up with CSR’s foreign policy working group. The result, in June 2017, was a joint presentation on Russia’s foreign policy and global positioning, with perspectives from 2017 to 2024.46Ivan Timofeev, Theses on Russia’s Foreign Policy and Global Positioning (2017-2024), Russian International Affairs Council and Center for Strategic Research, June 2017, https://russiancouncil.ru/papers/Russian-ForeignPolicy-2017-2024-Report-En.pdf. As part of the project, RIAC conducted thirty interviews with diplomats, experts, media specialists, and entrepreneurs, and developed several case studies. Among other things, the report suggested that “Russia is an integral part of European civilization” and argued that the “underdevelopment of the Russian economy and governance institutions poses a much more significant threat to the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity than any realistic military threats.”47Ibid, 5, 27. Moreover, Council experts participated in another policy report presented by CSR in April 2018 defining seven strategic priorities for Russia’s development until 2024, particularly regarding the country’s integration into the global economy and the use of its foreign policy as a tool for economic development.48“Ключевые позиции в мировой экономике,” Center for Strategic Research, last updated April 18, 2018, http://2035.media/2018/04/18/economic-positions/.

Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISI)

RISI emerged by presidential decree in February 1992 from the basis of the Scientific Research Institute for Intelligence Problems, which had been part of the counterintelligence arm of the Soviet Committee for State Security (KGB) under Yuri Stsepinskiy. Despite these origins, RISI was established as a new state-sponsored institute, formally independent from the intelligence services. In April 1994, Stsepinskiy was replaced by the academic historian Yevgeny Kozhokin, who had been elected to the first Soviet Russian parliament, the Congress of People’s Deputies, in partially free elections. Directly before his appointment to RISI, he served as deputy chairman of the State Committee for Federal and National Affairs.

When Kozhokin took the helm, RISI consisted of no more than fifty analysts with varying backgrounds, including former intelligence officers and civilians. In addition, a considerable information department collected and analyzed open-source materials. During his fifteen years as director, Kozhokin brought many new researchers to the Institute, particularly from his alma mater, Moscow State University. He established the study of the post-Soviet space as one of the Institute’s signature areas and turned RISI into a respected institution. In 2007, the Institute employed arguably around seventy researchers, working on international security, the near abroad, military-strategic questions, international economic security, and market economic issues.49Нина Беляева and Дмитрий Зайцев, Сравнительный российских и зарубежных центров: case study (Москва, Государственный Университет Высшей Школы Экономики, 2007), 118.

For most of Kozhokin’s directorship, however, the Institute remained almost invisible to the public. That started to change in April 2009, when Medvedev turned RISI into a federal scientific institution financed by the presidential administration, with the president as its founder. Its research activities were tied to the strategy and priorities outlined in the president’s annual address to the Federal Assembly. In consequence, the Institute added new departments, received more resources, and increased its public activities substantially. At the same time, Medvedev dismissed Kozhokin and appointed Lieutenant General Leonid Reshetnikov, who had just retired from the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), as director.

Given the opportunity and financial means, Reshetnikov and his new team made several important changes. First, the Institute established several regional information-analytical centers in Russia and appointed contact people abroad. Whereas the Institute had only one such center in Kaliningrad (since 1996) under Kozhokin, new offices were opened in Rostov, St. Petersburg, and Yekaterinburg from August to November 2009. Moreover, in April 2011, Reshetnikov established another center for regional and ethno-religious studies in Kazan. After the annexation of Crimea, similar centers were opened in Simferopol and Sevastopol in April and September 2015, respectively. In addition, since March 2014, RISI opened an information center in Tiraspol. Finally, over the course of 2013, RISI appointed individual representatives in Helsinki, Belgrade, and Warsaw, some of whom have since been expelled from the respective countries.

Second, the corps of analysts at RISI increased to more than 120, with more than 200 total employees. An analysis of available biographical data suggests that most of the researchers employed in 2016 had joined RISI after 2009, sometimes directly after graduating from university.50Alexander Graef, “Russia’s RAND Corporation? The Up and Downs of the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISI),” Russian Analytical Digest No. 234 (2019), 6, https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000331035. Reshetnikov himself added the Humanitarian Research Center as a new department, with the aim to study “the contentious issues of foreign relations history and the role of the religious factor.”51Alexandra Kononeko and Alexander Kornilov, “The Russian Institute of Strategic Studies: The Organizational Dimension,” Bilge Strateji 6, no. 10 (2014), 18. He also brought several new personal advisers to RISI, including former diplomat Vladimir Kozin, who became a frequent commentator on questions of arms control and US missile defense, and historians Petr Multatuli and Mikhail Smolin, both of whom support the restoration of the Russian monarchy.

Third, RISI’s publications became more frequent and diverse, as researchers were encouraged to publish for wider audiences and to be visible on state TV and in the news. In late 2009, RISI launched the quarterly Problems of National Strategy journal (published every two months since 2012) and in 2012 founded its own book series on religious-historical themes in cooperation with the FIV publishing house, owned by Smolin. Under Reshetnikov, the institute also established RISI TV and since 2014 has shot several films, particularly on Ukraine, making the case for the Crimean annexation based on the peninsula’s cultural affinity with Russia.

From 2009 to 2016, Reshetnikov’s political views were integral to the institute’s work and reputation. Reshetnikov sees Russia as a distinct Christian civilization in an eternal political and cultural struggle against the West, particularly the United States. The nationalist shift in Russian foreign policy since 2012 has provided this worldview with ample scope for action. Under Reshetnikov, RISI actively promoted attempts to intensify the military conflict in eastern Ukraine, aiming at the creation of Novorossiya (New Russia) as a confederation to extend control over southeastern Ukraine.

In this context, at least two former employees have publicly argued that RISI’s work, particularly on Ukraine, was shoddy and highly ideological. Instead of profound analyses, the institute had fed political leaders propaganda and distorted information about the events in Ukraine and their prospective development, the former staffers argued.52Pavel Gusterin, “Леонид Решетников как стратег,” Voennoe Obozrenie, November 5, 2016, https://topwar.ru/103202-leonid-reshetnikov-kak-strateg.html. As a result, they said, the potential for a local insurgency against the central government in Kyiv had been overstated,53Aleksandr Sytin, “Анатомия провала: О механизме принятия внешнеполитических решений Кремля,” Bramaby, January 5, 2015, http://bramaby.com/ls/blog/rus/1841.html. contributing, at least from Moscow’s perspective, to a major foreign policy failure.

In the intra-Russian foreign policy debate, RISI also has been used as a way to police the activity of other Russian think tanks. In February 2014, RISI, together with the Center for Actual Politics, assessed the activity of eight Russian research institutions, networks, and think tanks, including PIR; the New Eurasia Foundation, led by RIAC Director General Andrey Kortunov; the RAS Institute of Sociology; and even the Russian International Studies Association, led by MGIMO Rector Anatoly Torkunov. The resulting report suggested that the organizations be made to register as foreign agents. “Positions contradicting Russian state interests have become a persistent part of mass consciousness and thinking among a considerable part of the Russian expert community,” the report said.54Методы и технологии деятельности зарубежных и российских исследовательских центров, а также исследовательских структур и ВУЗов, получающих финансирование из зарубежных источников: анализ и обобщение, Russian Institute for Strategic Studies and the Сenter for Actual Politics, February 2014, https://riss.ru/analitycs/5043/.

Although it is difficult to establish a direct causal relationship, some of the organizations in the report were made to register as foreign agents, forced to reduce their activities, or even dissolved. Main financial sponsors, such as the MacArthur and Open Society foundations, were declared “undesirable organizations” and banned. The report poisoned the relationship between the Russian academic expert community based at MGIMO and the RAS institutes on the one hand and the RISI leadership on the other. Institutional links were cut, although cooperation with individual researchers continued. Reshetnikov’s academic reputation was in tatters.

Overall, the status of the ‘big four’ foreign policy think tanks in Russia depends on existing interpersonal relations with political power that ensure both direct state funding and/or intellectual sponsorship”

Mikhail Fradkov (left) and Leonid Reshetnikov (right) at a meeting with Vladimir Putin (center) on January 31, 2017, at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia. Source: Kremlin.ru

In November 2016, Putin replaced Reshetnikov with SVR Director and former Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov, who still leads RISI. Speculation about the reasons for the shakeup ranges from political leaders’ dissatisfaction with RISI’s analytical work and its dominant monarchist-religious orientation to its alleged hand in failed Russian attempts to undermine Montenegro’s accession to NATO.55Christo Grozev, “Balkan Gambit: Part 2. The Montenegro Zugzwang,” Bellingcat, March 25, 2017, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2017/03/25/balkan-gambit-part-2-montenegro-zugzwang/ Some attribute Reshetnikov’s dismissal to successful lobbying by politically well-placed think tankers and researchers who were mentioned in the 2014 report.

Whatever the reason, institutional reforms launched in May 2017 by the new director discarded the religious agenda and led to a repositioned RISI. Fradkov dissolved the Center for Humanitarian Studies, and its director, Mikhail Smolin, along with several advisers close to Reshetnikov, left RISI. The entire leadership of RISI and almost all deputy directors were replaced. Moreover, Fradkov established a new Center for Research Coordination and rearranged some of the research centers. Several department heads were replaced. Arguing for the reorganization, Fradkov said, “We need to be more professional” and “produce work of high quality,” in a swipe at the quality of analysis produced by RISI under Reshetnikov.56“Структурная реорганизация в РИСИ,” Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, May 2, 2017, https://riss.ru/events/40480/.

Overall, the status of the “big four” foreign policy think tanks in Russia depends on existing interpersonal relations with political power that ensure both direct state funding and/or intellectual sponsorship. In this context, it is striking that apart from RISI, all other think tanks represent social networks and meeting points rather than institutes with permanent research staff. This fact highlights both their role as tools of Russian soft power directed at foreign audiences and platforms to consolidate the Russian expert community. Whereas SVOP has been able to selectively influence policy making in the 1990s, this role has been partially overtaken by RIAC. Here, the direct linkages that exist between the RIAC leadership and the Russian MFA are crucial to introduce ideas into the policy process. The Valdai Club, on the other hand, serves as the international mouthpiece of Russia’s foreign policy elite, enabling its members to participate in global debates. The exception to the rule is RISI as the research institute directly subordinated to the presidential administration. After seven years of maximum publicity following a monarchist-orthodox agenda, RISI’s work has once again become less accessible, stressing the in-house character of its analyses.

Part Two

Chapter 4: Foreign policy narratives since 2014

In the second part of this report, we look at Russia’s grand foreign policy narratives and their evolution after the Ukrainian crisis of 2014, as defined by the Russian foreign policy expert community. To that end, we focus specifically on reports, working papers, foreign policy concepts, and policy briefs published with RIAC, the Valdai Discussion Club, SVOP, and RISI.

Most of the materials that define Russian foreign policy discourse in its public form are published by the RIAC and Valdai Club. Both organizations seek to engage an international audience and therefore publish most of their work in Russian and English. Both have also built research partnerships with renowned foreign policy institutions around the world. For instance, of the thirty-one reports that RIAC has published57See RIAC’s full list of reports: “Publications,” Russian International Affairs Council, accessed June 20, 2019, https://russiancouncil.ru/activity/publications/. since 2014, seventeen were co-sponsored by international partners, including the Royal United Services Institute, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the European Leadership Network, the German Council on Foreign Relations, and the Atlantic Council of the United States.

As neither the Valdai Club nor RIAC has a large permanent staff, most of the work they publish is written or co-authored by foreign affairs experts from MGIMO, the RAS institutes, and the Higher School of Economics (HSE), among other organizations, thus representing a broader view of international relations and Russian foreign policy.

In this part of the report, we consider how Russian foreign policy experts have approached three major themes: First, the evolution of the concept of Greater Europe and how it defines Russia-EU relations today, specifically in the context of the Ukrainian conflict, the annexation of Crimea, and the war in The Donbas; second, the establishment of Greater Eurasia narrative and its relation to Russia’s pivot to the East, with a specific focus on Russia-China relations; and third, the evolution of the Russian foreign policy community’s attitudes to the concept of multipolarity and current world order.

Chapter 5: The end of Greater Europe

Russian understanding of what exactly Greater Europe is and could be has always been flexible. The term ‘Greater Europe’ refers to the entire geographic space between Iceland and Norway in the North and Turkey in the South and the space from Portugal in the West to Russia in the East. In the context of Russia foreign policy thinking since the 1980s, it was presumed that this macro-region could be tied together one way or another, not only due to economic, political, and security considerations but also largely to a common cultural and historic closeness. The details of this cooperation varied depending on political circumstances of the moment, but the idea that Russia and the rest of Europe would move closer to each other has been one of the most enduring narratives guiding Russia’s foreign policy community since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Much of Russia’s institutional cooperation with the West in the 1990s, including the Russia-EU Partnership and Cooperation Agreement signed in 1994, Russia’s accession to the Council of Europe in 1996, and the Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation, and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation signed in 1997, were motivated by a vision of Europe from Lisbon to Vladivostok.

The first half of the 2000s saw intensified institutional cooperation with the EU and aspirations to implement the four Common Spaces framework, which provided considerable incentives for the foreign policy community to further develop the concept of Greater Europe, envisioning deeper economic, institutional, and social ties. But political elites viewed this process differently than did the larger foreign policy community, as suggested58Igor Ivanov, “Speech at the Greater Europe Task Force Meeting, London,” (speech, Meeting of the Task Force on Cooperation in Greater Europe, London, December 11, 2015), https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-andcomments/analytics/rech-na-vstreche-rabochey-gruppy-proekta-stroitelstvo-bolsho/. by former Foreign Minister and current RIAC President Igor Ivanov in 2015. The proposals on Euro-Atlantic cooperation “were ahead of their time: the political elites in our countries were not prepared for such groundbreaking ideas,” Ivanov explained. “We should learn this lesson. We need to be more realistic and develop proposals that reflect the political situation. That means not falling behind, but also not racing ahead of ourselves.”59Ibid.

By the early 2010s, much of the Greater Europe agenda had been reduced to talks about possible visa liberalization, economic ties, and cultural, academic, and civil society cooperation. The evolution of Russia’s political system, especially after Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, constrained considerably the Greater Europe agenda that had been a pet project of the expert community. Still, the idea has not been discarded altogether, despite the clear divergence of political goals in Russia and the EU. The annexation of Crimea and the war in the east of Ukraine created enormous differences in Russian and Western assessments of the Ukrainian conflict and its causes, prompting a raft of eulogies for the Greater Europe vision.

Ukraine: Cause or consequence?

While nearly all American and European experts see Russia’s annexation of Crimea as a violation of international law that openly breached Ukrainian sovereignty and created multiple risks for European and global security,60Managing Differences on European Security in 2015, Russian International Affairs Council, Atlantic Council, and European Leadership Network, March 26, 2015, https://russiancouncil.ru/en/activity/publications/managingdifferences-on-european-security-in-2015/. the Russian expert community publicly presents quite different views on the events of 2014. The most exotic take on the roots of the Ukrainian crisis came from RISI under Reshetnikov’s leadership. In an October 2014 report61“The Ukrainian Crisis: Instrument of Geopolitics of the West,” Russian Institute for Strategic Studies: RISI Analytical Review 6 (2014), https://riss.ru/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/AO_2014_ves-tekst.pdf., RISI combined the most dominant conspiratorial views of Western policy toward Ukraine, asserting that the Ukrainian revolution of 2013-2014 was a Western plot aimed at “waging an informational, economic, political, and possibly military assault on Russia.”62Ibid., 4. According to the report, Russia is thwarting the creation of a new world order that US “business and political elites” have been trying to create for the last couple of decades. Moreover, the authors claimed that the United States planned to evict the Russian military from the Crimean Peninsula to construct US military bases on the Black Sea coast. Russia’s pushback in Ukraine, according to RISI experts, prevented the creation of a global society of “chipped and nanorobotized transhuman bio-objects, semihuman-semicomputers.” In later interviews, Reshetnikov doubled down, telling Komsomolskaya Pravda in October 2015, for instance, that “regardless of its leaders, Ukraine can exist only as a state hostile to [Russia], or as no state.”63Михаил Панюков, “Леонид Решетников: Русофобы продержатся на Украине еще максимум 20 лет,” Komsomolskaya Pravda, October 15, 2015, https://www.kp.ru/daily/26444.7/3314664/.

It must be noted that RISI’s take on this issue is an outlier, even for the most conservative parts of Russia’s foreign policy community. But even though RIAC and Valdai Club experts do not cite wild conspiracy theories about Ukraine, they do tend to both overlook the fact of Ukraine’s political agency and see the conflict through the prism of post-Cold-War relations between Russia and the West. RIAC experts attribute the Ukrainian crisis to flaws in the Euro-Atlantic security architecture, which since the collapse of the Soviet Union has become “less transparent, less predictable, and less stable than in the twentieth century.”64Managing Differences, 2. This deterioration, these experts say, is due to the failure of Russia’s Western partners to understand Russia’s security concerns and their rejection of Russia’s proposals to create a joint European security architecture that would treat all parties involved as equal. A September 2014 report65Украина: Предпосылки Кризиса и Сценарии Будущего, Valdai Discussion Club, September 2014, http://ru.valdaiclub.com/files/22576/. by the Valdai Club claimed that Russia annexed Crimea because the Kremlin realized it was being cheated by the West. EU and US backing for the Ukrainian revolution, it argued, was not motivated by a desire to support democracy and human rights, but to kick out the Russian fleet from Crimea and to admit Ukraine to the EU and NATO. The report asserted that Russia’s annexation of Crimea was not a goal in and of itself, but a response to two and a half decades of the West dismissing Russia’s national interests. The report also claimed that even a hypothetical resolution of the Ukrainian crisis today would not lead to “business as usual,” as the very basis of Russian-Western relations needs to be reconsidered.

Ultimately, Russian foreign policy experts considering the causes of the Ukrainian conflict ended up in a similar place as they had on the concept of Greater Europe. The West and Russia have failed to understand each other’s position, RIAC President Igor Ivanov argued.66Ivanov, “Speech.” The West had expected Russia to recognize Western institutions as superior and adapt to Western rules of the game without considering Russia’s specifics and ambitions, while Russia had expected that building a Greater Europe would lead to some sort of compromise between the two, he said. Since Russian leadership values being treated as an equal partner much more highly than being part of the West, this conflict seemed unavoidable. Although the vast majority of experts agree that the crisis in Ukraine has scuttled old expectations and models of relations with the West, they disagree on how Russia should proceed with damage control. SVOP’s 2016 strategy on foreign policy—co-authored by Karaganov, Bordachev, and a couple of experts from the Higher School of Economics,67Cтратегия для России: Российская внешняя политика: конец 2010-х–начало 2020-х годов, Совета по внешней и оборонной политике, May 23, 2016, svop.ru/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/тезисы_23мая_sm.pdf.—argued that the conflict in The Donbas will not be solved anytime soon, so Russia should keep it in a “frozen” state.