Social lockdowns have been essential in the battle against the current COVID-19 pandemic. However, while these lockdowns have succeeded over time in “flattening the curve” (slowing the rate of infections to levels that local healthcare systems can withstand), the strategy has side effects. The catastrophic economic impact of keeping people at home has alarmed policymakers across the globe. Less noticed is the particular harm inflicted on one demographic – women.

Globally, almost 250 million women and girls between the ages of fifteen and forty-nine suffer physical or sexual violence at the hands of an intimate partner each year. These numbers are set to skyrocket, however, as the health, security, and financial worries caused by the coronavirus outbreak intensify domestic tensions and force families to lock down in what is statistically the most dangerous place a woman can be: her home. Home isolation orders present abusers with increased opportunity to inflict harm on victims who are rendered more vulnerable by reduced access to their support networks and limited options for escape from the home. Governments struggling to respond to the coronavirus epidemic have failed to respond to this spillover effect – and to a similar crisis affecting vulnerable children – with increased services that cater to those at risk. This has left domestic violence response centers overwhelmed by the heightened demands on their services.

The nations of the Global North – such as Canada, Germany, Spain, the UK and the US – suffered early waves of the pandemic and have already reported stark increases in demand for emergency shelters. As the pandemic spreads to Africa, the incidence of domestic assault is increasing there, too. In South Africa, where COVID-19 cases have been concentrated, 148 people have been arrested and charged with crimes relating to gender-based violence (GBV), and over 2,000 complaints of GBV were made to the South African Police Service in first seven days of the lockdown.

With an alarming 4,793 confirmed COVID-19 cases, South Africa has the largest number of COVID-19 infections on the continent, prompting President Cyril Ramaphosa to declare a twenty-one day nationwide lockdown beginning on March 27. Part of this initiative included the deployment of 24,389 security forces responsible for the enforcement of this strict policy. One of the very few countries to enforce exceptionally strict policies, the South African government has also prohibited the sale of cigarettes and alcohol, which have been identified as catalysts for domestic violence as well as immune system suppressants.

While these policies have apparently been effective at slowing the transmission of COVID-19, South Africa has experienced a wave of crime, including an increase in robbery, vandalism and gender-based violence. In an open letter to the South African people, President Ramaphosa condemned these “despicable” actions and reaffirmed his commitment to prioritizing responses to gender-based violence in the national COVID-19 response. He also promised unbroken commitment to the Emergency Response Plan to end violence against women and children that was introduced in 2019. Additionally, the GBV National Command Centre, which operates a national call center facility, has remained fully operational – and reports that it has received 12,000 calls since the implementation of the lockdown.

Prior to the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, rates of gender-based violence in South Africa were among the highest in the world. According to government reports, a South African woman is murdered every three hours on average, with many assaulted and raped before their demise. The rate in violence against women had already ignited protests in many parts of South Africa, leading the government in September 2019 to recognize the dire state of women within the country by declaring gender-based violence and femicide a national crisis.

South Africa is not alone. In Kenya, the National Council on Administration of Justice has also reported a spike in sexual offenses, and has identified the primary perpetrators as “close relatives, guardians, and/or persons living with the victims.”

Human Rights Watch has reported that one 16-year-old Kenyan girl was captured and sexually assaulted by a man who reportedly kidnapped her because he “needed female company” in order to get through the lockdown. Fortunately, she was rescued by neighbors and is now in a safe house. But violence is the daily reality for women and girls across Kenya, where 45 percent of women and girls aged fifteen to forty-nine have experienced physical violence and another 14 percent have reported experiencing sexual violence. (The true rate of violence is likely much higher due to the typical under-reporting of sexual crimes.)

Heightened rates of intimate partner violence during the pandemic should not have taken authorities off guard. During the 2014-16 Ebola virus outbreak that ravaged through some West African countries, there was similar evidence confirming that the safeguard measures implemented to prevent the spread of the Ebola virus also rendered women extremely vulnerable to GBV, and particularly increased the risk of sexual violence. Additionally, as resources for reproductive and sexual health were redirected towards the emergency Ebola response, many countries saw accompanying increases in maternal mortality. Should this pattern continue, there will be larger consequences for women and girls, beyond exposure to the virus.

UN Women has advocated loudly for actions to address this “shadow pandemic” of sexual violence. Under the leadership of the Executive Director, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, it has issued a series of recommendations to help governments, international and national civil society organizations, and United Nations (UN) agencies to curb the widespread violence against women and girls across the globe. These recommendations include allocating additional resources to address sexual violence in national COVID-19 response plans; strengthening services for women who experience violence – i.e. expanding capacity of shelters, strengthening hotlines, and ensuring psychosocial support; and placing women at the forefront of policy changes, solutions and recovery strategies. The UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women has also established a COVID-19 Funding Window, which aims to support existing civil society organizations and fund new projects specifically designed to support women and girls who experience violence in the context of the pandemic.

Given that the time for preparation in most countries is already long gone, governments need to take these recommendations as more than friendly suggestions. Women cannot continue fall through the cracks during times of crisis, especially given that many women in Africa become the primary caregivers for their families in times of poor health. Restricting people to their homes is the best way to contain the virus, no doubt, but in doing so it is important to recognize that many for many women, the home is not a safe haven. Too many lives have already been lost to the virus, so governments and civil society must do what they can to protect those women who are now doubly vulnerable.

Joanne Chukwueke is an intern with the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

Questions? Tweet them to our experts @ACAfricaCenter.

For more content, go to our Coronavirus: Africa page.

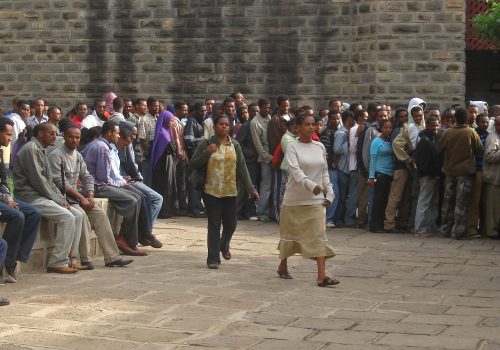

Image: A Central African woman prepares food in the Ngam refugee camp of Adamawa region, Cameroon. (Flickr/UN Women/Ryan Brown)