Could the IRGC pull a Wagner Group move in Iran? That’s what some Iranians are hoping for.

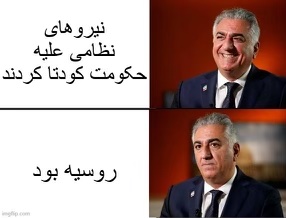

“Military forces staged a coup against the regime… It was Russia,” said a meme depicting a smiling, then disappointed former Iranian Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi. When Wagner Group mercenaries, led by Yevgeniy Prigozhin, advanced toward Moscow—reaching within 125 miles of the capital within twenty-four hours—to take down Russia’s military command on June 23-24, it was not just Ukrainians watching with schadenfreude and hope. Many Iranians—both inside Iran and in the diaspora—wondered what it meant for the Islamic Republic’s future if Russian President Vladimir Putin, one of the clerical establishment’s top allies, was taken down.

Upon news of the Prigozhin-led rebellion, Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Telegram channels quickly covered the breaking story. One viral screenshot of the IRGC’s main channel reposted a tweet by a pro-regime journalist emphasizing, “If necessary, just as we prevented the fall of [Bashar al-]Assad, we will prevent the fall of #Putin.”

The upper echelons of the Islamic Republic were quick to respond to the events. “The Islamic Republic of Iran supports the rule of law in the Russian Federation,” noted the Foreign Ministry spokesman on June 24 without any mention of Putin, adding that the mutiny was a “domestic affair.” Russian media reported that Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi spoke with Putin on the same day, but didn’t provide any details on what was discussed. Meanwhile, the Iranian foreign minister spoke with his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov regarding “developments related to the situation in some regions of Russia”—a reference to the events in Bakhmut, where the rebellion came to a head. Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian said that Moscow would “pass this phase” and warned against “foreign interference.”

State media outlets gave a better sense of how the higher-ups interpreted the revolt. Nour News, closely tied to the Supreme National Security Council, tweeted that, although the Wagner Group could have “destructive psychological effects due to its involvement in the Ukraine war,” the group “lacks the necessary strength to challenge the Russian army.”

Meme’d scene from Braveheart

After the Wagner Group rebellion seemingly ended, on June 25, state media outlets covered the events with front-page headlines that mostly took jabs at the mercenary leader and his forces. Hardline daily Kayhan played into common conspiracy theories blaming the West and NATO. A headline for the hardline newspaper Javan read, “Treacherous dagger did not cut it,” referring to Prigozhin stabbing Putin in the back. Even pro-regime social media users made light of the events, with one posting a meme’d scene from Braveheart, with Ukraine and the United States watching gleefully as Wagner and Russian fighters are about to clash, only to see them kiss and make up.

Reformist papers took a slightly nuanced approach. Pro-reform Hammihan newspaper published an op-ed about how the rebellion may be an “alarm bell” for Tehran not to rely solely on the East—a reference to China and Russia. Similarly, a dissenting voice came from the former head of the parliament’s National Security and Foreign Relations Committee, Heshmatollah Falahatpisheh. He argued that “it was naturally clear that Putin cannot have a stable future” and that Russia was heading “back to the [Boris] Yeltsin period.”

None of these reactions are much of a surprise. A pro-Russia angle was expected from the Islamic Republic, given that it is one of Moscow’s main military backers.

Since the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Iran has been providing hundreds of attack drones to Russia and is currently delivering materials to build an Iranian unmanned-aerial-vehicle manufacturing plant east of Moscow. The two countries are also heavily relying on one another as part of a sanctions evasion axis, having reportedly conducted $4.9 billion in trade during 2022 (up 20 percent compared to 2021).

There’s a soft power element as well, with Russian tourists making Iran a top three tourist destination (after Turkey and India). Additionally, a historical drama series named Khatoon (“Once Upon a Time in Iran”), which portrays the Anglo-Soviet occupation of Iran during World War II, became a point of controversy in Iran for not depicting Moscow favorably.

Whereas official organs of the Islamic Republic attempted to downplay the events in Russia, many Iranians joked on social media about the possibility of the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei getting “orphaned if Daddy Putin falls,” while one asked how much it cost to “rent the Wagner Group for a week” in order to take out Khamenei. Another Iranian quipped that it was as if the late IRGC Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani and the Supreme Leader were going head-to-head and that the former was coming to take Tehran.

That last tweet was particularly reflective of the thoughts of a portion of Iranian society, as they pondered whether similar events could play out in Iran in the near future. For years, some Iranians have held on to the idea that when the Supreme Leader eventually passes away, the IRGC would take the helm of the country in the form of a social liberal military dictatorship—something that has only intensified in recent months due to the ongoing anti-establishment protests that began in September 2022. Separately, Pahlavi, a leading Western-based opposition figure to the Islamic Republic, has repeatedly called on IRGC members who have not committed atrocities to defect and join the people to overthrow the regime (hence the meme at the beginning of the piece).

While the IRGC is no monolith and has its own external operations arm—the Quds Force, which could arguably have parallels drawn between it and the Wagner Group (the former is also state-funded but has roles in conflicts such as Libya, Mali, and Ukraine), it is best to stay clear of such comparisons.

The role of the IRGC since the 1980s was to protect the Islamic Republic from inside and outside threats, including mass uprisings, coup d’états, and foreign interventions. Consequently, the IRGC shares the ideology of the Velayat-e Faqih itself. Since Khamenei became Supreme Leader in 1989, the IRGC has played a larger role not just domestically—by controlling much of the Iranian economy, swaying elections, and crushing dissent—but also externally, with its involvement in countries in the region (Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen). It is highly unlikely that the IRGC would defect in its entirety from the clerical establishment to overthrow its leadership.

What the IRGC continues to do is have its members occupy high positions in government, with the Raisi cabinet having the most positions occupied by the IRGC compared to past administrations. The Guards will continue to maintain a key role as the right hand of the next Supreme Leader whenever succession does occur.

Given the news out of Russia, like much of the international community, the security and intelligence apparatus of the Islamic Republic was watching the events closely to see its outcome. Had Prigozhin followed through with his plans and succeeded at ousting Putin, Tehran’s calculations with one of its top allies would’ve had to adjust accordingly. However, an aborted attack on Moscow is merely seen by Tehran as a nuisance for Putin in the same way that the Russian president likely views the ongoing anti-regime protests in Iran as an annoyance for the clerical establishment. In November 2022, Raisi and Putin discussed deepening bilateral ties at the height of protests in Iran, and the Russian president reportedly didn’t even bring up the unrest.

For those betting on the IRGC, perhaps the lesson of the Wagner Group’s failed rebellion in Russia—which was about a personal vendetta against an authoritarian leader more than anything—is that only the people of Iran and Russia can control their destinies.

Holly Dagres is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs and editor of the Atlantic Council’s IranSource blog. She is also the author of the “Iranians on #SocialMedia” report. Follow her on Twitter: @hdagres.

Further reading

Wed, Jun 28, 2023

The Wagner rebellion is over—for now. But how will the events reverberate in the Middle East and North Africa?

MENASource By Mark N. Katz

The June 23-24 rebellion led by Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin—aimed, he claimed, at replacing the Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov (not Russian President Vladimir Putin)—has ended. However, reverberations from it are likely to continue being felt beyond Russia, such as in the Middle East and North […]

Wed, Jan 11, 2023

Soccer players versus the IRGC. Who do the people of Iran choose?

IranSource By

Iranians know who their national heroes are.

Tue, Jan 24, 2023

Can Reza Pahlavi help unite the Iranian opposition? A hashtag is suggesting so.

IranSource By

An Iranian journalist started the hashtag #You_Represent_Me, which was quickly picked up by thousands of other Iranians, inside and outside the country, who used it to declare their support for Reza Pahlavi.

Image: An Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) military personnel stands in front of portraits of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (R), and Former commander of the IRGC’s Quds Force Qasem Soleimani, after a ceremony in the Iranian Interior Ministry building in downtown Tehran, on April 14, 2022. (Photo by Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto)