Japan balances Tehran and Washington

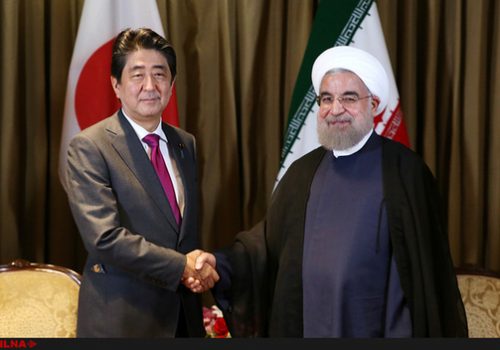

On December 19, Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani visited Japan. The two-day visit was the first by an Iranian president since 2000. It also marked the third meeting between Rouhani and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe this year.

The Tokyo meeting covered an array of issues. The talks ranged from finding a means to utilize Iran’s oil export income from Japan—which continues to be held in Japanese banks due to US sanctions—to Tokyo’s plan to dispatch the Self Defense Forces (SDF) to the Persian Gulf region for “investigation and research.”

More importantly, according to the Japanese Foreign Ministry, Prime Minister Abe requested Iran fully comply with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), as the country continues to reduce its commitments in response to the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the multilateral accord in May 2018. Abe also conveyed concerns about the recent demonstrations that have spread across Iran, urging Tehran to use utmost restraint.

Japan is aware that the visit by President Rouhani has been harshly criticized by hardliners in Tehran, who were skeptical about the benefits of a visit for Iran. Tokyo understands the skepticism may be fueled not only by the rivalry between factions within the Islamic Republic but also by close relations between Japan and the United States—as demonstrated by Abe discussing the meeting with US President Donald Trump immediately after Rouhani left for Tehran.

Japan is also aware that many believe Iran was behind the attack on a Japanese owned oil tanker in mid-June, during Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Tehran—while he was in a meeting with the country’s Supreme Leader.

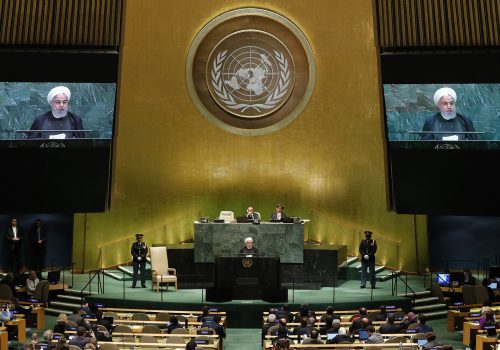

However, Japan has never cast blame for the oil tanker attacks. Instead, Abe held a bilateral meeting with President Rouhani in September on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York—less than two weeks after the Saudi Aramco oil facility attacks—to discuss the importance of stability in the Persian Gulf region.

Prime Minister Abe has consistently sought diplomacy to bring stability to the Middle East. Firstly, Japan depends on the Persian Gulf region for its oil. More than 80 percent of Tokyo’s oil imports come from the region. Even when Iran’s crude oil production decreased considerably during the 1979 revolution and eight-year war with Iraq, Japan’s level of dependency on Persian Gulf oil remained high at around 70 percent. Thus, Tokyo has no choice but to pursue diplomatic efforts to bring stability.

Secondly, Prime Minister Abe considers it essential to hold direct talks with President Rouhani about his intention to dispatch the SDF, specifically a Japanese destroyer and patrol plane, to the Persian Gulf region—though it will not enter the Strait of Hormuz. While the dispatch is a response to Trump’s announcement in June that all countries protect their own ships instead of relying on the US “for zero compensation,” it is also in line with a more active Japanese approach to its security.

Established following World War II, the SDF is designed to be a solely defensive force whose mission is strictly restricted by the Japanese Constitution, which renounces war. Therefore, if the SDF is dispatched to the Persian Gulf, what it can do to protect Japanese ships would actually be quite limited. However, the Japanese Government has made the decision as an attempt to normalize its security stance.

Iran has repeatedly said that it is the responsibility of regional countries and not outside powers to protect the stability of the Persian Gulf region. In an attempt not to alienate neither Iran nor the United States, Tokyo has chosen to dispatch the SDF independently and not part of the US-led naval “coalition of the willing” that the Trump administration has invited its allies to join.

President Rouhani’s response was unequivocal. He expressed appreciation that Japan welcomed his Hormuz Peace Endeavor (HOPE) initiative and understood that Japan needs to protect its ships. President Rouhani’s “consent” was one of the leading news items that the Japanese media took up after his visit concluded.

President Rouhani, on his return to Tehran, mentioned that Japan was once the first country to break the British economic blockade of Iran in 1953, during the oil nationalization era, when a Japanese tanker directly bought oil from Iran. He may be expecting Japan’s proposal to utilize Iranian oil export income to happen.

The unprecedented US maximum pressure campaign accompanied by effective sanctions seems to be making things much harder for Iran compared to 1953. However, it does not mean that Japan has to give up the need to ease tensions to improve the stability of the Persian Gulf region in today’s circumstances. In this sense, Japan’s effort to find a diplomatic solution to alleviate tensions can only continue, regardless of the expectations from the United States and Iran.

Sachi Sakanashi is a senior research fellow at the JIME Center, Institute of Energy Economics, Japan (IEEJ).

Image: Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani meet in Tokyo, Japan, December 20, 2019 (Reuters)