Arab states are normalizing with the Assad regime. This is the Middle East’s 1936 moment.

With tensions between the West and the Russia-China-Iran axis escalating, observers increasingly resort to ever-alarming historical analogies to avert a sleepwalk to disaster. The standoff between the United States and Iran, for example, was likened by one think tank to a 1914 moment where “a small incident could blow up into region-spanning conflict.”

More recently, Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territory was equated to Germany’s 1938 takeover of Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia, and China’s naval build-up that challenges US supremacy in the Pacific was said to echo the pre-World War I Anglo-German arms race. Even the September 11 terrorist attacks were said to be “the Pearl Harbor of the twenty-first century.” How useful any of these parallels are is debatable. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s worldview “lives in historic analogies and metaphors,” which doesn’t seem to have inspired great decision-making. Comparisons with the past, however, can be useful in making sense of events that appear nonsensical on the surface.

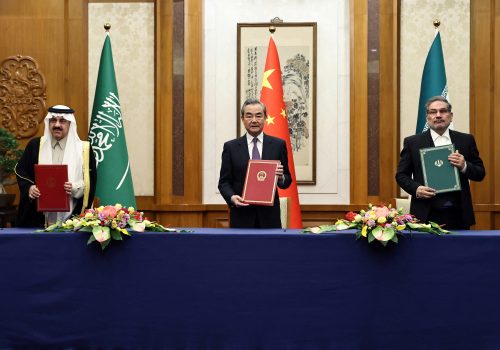

A prime example is the increasing pace of Arab normalization with Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad. For instance, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has, for years, been very keen on rehabilitating the Assad regime, which is accused of war crimes, gross human rights violations, and the forced displacement of 13 million Syrians. In a recent visit to Abu Dhabi on March 19, the UAE gave Assad the full red-carpet treatment in a brazen display of defiance against the United States and its European allies who insist on continuing to ostracize him. Oman, another West-friendly Gulf country, did the same on February 20.

Now diplomatic relations are set to be restored between Syria and two behemoths of the Arab League: Egypt and Saudi Arabia, who are the holders of the all-important veto on Assad’s return to regional respectability. While the two Arab states are considered Western allies, they appear to be acting contrary to Western policy. This rush to part ways with more than a decade of West-Arab consensus on Syria is even more puzzling given that Assad has little to offer the Arabs except for a likely bill for reconstruction, which could amount to $400 billion.

Analysts have come up with, at best, speculative explanations for why the normalization drive is shifting gears. A reoccurring argument is that Arab states have concluded that de-escalation and regional coordination serve their interests more than confrontation among themselves and with Iran and Turkey. This is a convenient take and one that is based on a less-than-verifiable assessment that the culmination points of several regional conflicts have been reached simultaneously, including those in Syria, Yemen, Lebanon, and Iraq.

A second argument is that states such as the UAE have their eyes set on lucrative reconstruction contracts, but it is never explained who would actually pay for them. Certainly not Russia or Iran, who have their own domestic economic worries, and not China either, which avoids investing in unstable war zones. Additionally, there is the idea of authoritarian solidarity, an understandable impulse but one that is insufficiently convincing alone. Interestingly, some suggest that Assad is using the Captagon card—a multi-billion dollar amphetamine smuggling operation run by his family—to leverage his position vis-a-vis Jordan and the Arab Gulf states. This might be an item on the agenda, but, as long as Arab states do not compensate Assad for the loss of drug income, the rules of war economy suggest that the trade will continue. Last but not least, balancing Iranian influence in Syria has also been suggested as a reason for normalization. However, Iran has actually welcomed the Arab embrace of its Syrian proxy.

There is another, more convincing explanation, and it has nothing to do with Assad or Syria per se. To expound, one needs to go back to 1936 and a largely forgotten decision by Belgian King Leopold III, when he canceled the Franco-Belgian Military Accord meant to deter German aggression and reverted to a policy of strict neutrality. According to historian Pierre Henri Laurent, “Belgium sought this dramatic alternation of its international status as a response to the vast transformation of Europe from 1933 to 1936.” In other words, the policy of neutrality was a direct response to the growth of German power under Adolf Hitler and the obvious weaknesses of the French and British positions.

Today’s Arab rulers are like Leopold III: scared. They look around and see an assertive China challenging US hegemony, a revanchist Russia gobbling territory in Europe, and an Iran that is an ally and appears to be winning in all its regional proxy wars. On the other hand, America’s allies in the Middle East are losing everywhere. Whether it be the pro-West leaders of Iraq and Lebanon, the various shades of Syrian opposition, or the Saudis and Emiratis in Yemen, being an ally of the West means likely being outfought, outmaneuvered, and outwitted. For Arab states with limited military resources and fragile economies that cannot withstand instability, this is no laughing matter. Should the situation escalate, the region’s strategic location would make them particularly vulnerable. In the case of an all-out military conflict, their chances of autonomy would perhaps be no better than Belgium’s in 1940

The Arab normalization drive with Assad—enabled by Russia, China, and Iran—challenges the West’s “rules-based“ global order. It can be read as part of a wider development towards a multipolar order akin to a twenty-first century Congress of Vienna, where American power is balanced by a powerful Eurasian alliance. In this light, Arab states normalizing with Assad are not necessarily signaling their faith in the Syrian dictator, who they know is duplicitous and has little to offer them, or in Syria as a state, which is broken and likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.

Instead, Arab states are making a public—and what they would consider a sensible—commitment to neutrality amid a global struggle for domination between two competing power blocs that they see as morally equivalent. This hedging of bets is considered smart politics, much as Leopold III had thought of his reversal of opinion in 1936. The inadvertent winner of all this is Assad, who is happy to be a barometer for the anti-West axis’ success: the more he is normalized, the more ridiculous the West looks. Moreover, indulging him is a convenient way of currying favor with Moscow, Beijing, and Tehran and, given the current irresolute state of US policy on Syria, carries little risk of censure beyond a verbal slap on the wrist.

Western leaders should understand that the era where they could dictate terms to Arab allies is coming to an end. With its heavy military footprint and political clout, the US will continue to play the role of a major ally and security guarantor for the time being. Thus, Arabs have no reason to simply abandon this strategic relationship. However, they will seek a more neutral position by diversifying their alliances.

From this perspective, mending fences with Assad signals a shift away from the West without cutting ties with established partners. Attempts to enforce the ostracization of Assad through pressure alone—including the threat of sanctions—might just accelerate the erosion of Western influence in the Middle East. This might be a hard pill to swallow. Nevertheless, the alternative would amount to tilting at windmills, given that securing a sustainable place in the emerging multipolar world order is a matter of survival for Arab states. This incipient new order cannot be averted, but it can be shaped to encompass a large degree of Western values and norms. For that to happen, Western leaders need to stop considering power in the region as a zero-sum game, but as a competition for the best ideas and offers that can create new qualities of alliances.

Malik al-Abdeh is a Syria affairs expert and managing director of Conflict Mediation Solutions, a London-based consultancy specialized in Track II work.

Lars Hauch is a researcher and policy advisor for Conflict Mediation Solutions. Follow him on Twitter: @LarsHauch.

Further reading

Fri, Mar 17, 2023

The earthquake in Syria: A crisis of nature and politics

MENASource By

Politics is the art of the possible, and the tragic earthquake has put Syria on the priority list again.

Tue, Mar 21, 2023

China’s mediation between Saudi and Iran is no cause for panic in Washington

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

The deal is a mere statement of intentions by both countries to improve relations, meaning reconciliation is not complete.

Thu, Feb 9, 2023

In Syria, the earthquake ‘did what the Assad regime and Russians wanted to do to us all along’

MENASource By Arwa Damon

While aid increasingly flows into Turkey from around the world by air, land, and sea, areas on the other side of the border in Syria’s rebel-controlled areas are seeing none of that.

Image: Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, President of the United Arab Emirates, bids farewell to Bashar Al Assad, President of Syria, at the Presidential Airport in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates March 19, 2023. Abdulla Al Neyadi/UAE Presidential Court/Handout via REUTERS