How OPEC+ oil cuts accelerate China’s push for multipolarity in the Middle East

The United States is right to show frustration at the October 5 decision of the thirteen oil-producing countries making up OPEC+ to cut oil production by two million barrels per day (BPD) This is because officials in Washington don’t only see the struggle with Russia in Ukraine as a defining moment that will shape the future of the world order, but also see American predominance over historical allies and partners dwindling in favor of fierce competitors like China and Russia.

This was evident in the magnified reaction by some prominent members of Congress calling Saudi Arabia, the de-facto leader of OPEC, an “ally” of the US’s “greatest enemy,” Russia.

Washington’s fury towards some of its Middle East partners emanated, by and large, from a distorted mutual understanding between both sides, a natural prerequisite for what Jonathan Panikoff, the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative, called “misaligned expectations.”

Misaligned perceptions

Expectations between allies remain aligned as long as they share the same perception of the strategic environment they operate in. Thus, a misaligned perception of the historic shifts the region is witnessing is the core underlying epidemic currently ripping through the alliance, and “misaligned expectations” is just a visible symptom.

The issue of having different notions about the causes of the shifts in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) (and their consequences) lies in the conflict between the United States’ new great-power competition narrative and MENA countries’ struggle to maintain their agency. Although many countries worldwide have started to feel the weight of the US-China race for prevalence, the United States, so far, seems to be oblivious to their views.

In the Middle East, this is happening because regional countries’ drive for more “strategic autonomy” to achieve their interests has been recently seen as an analog for anti-American behavior. This is not to say that the Joe Biden administration—and Donald Trump administration before it—object to the rise of regional self-determination. However, the worry is that a desire for increased independence works hand-in-hand with China’s push for greater autonomy and less US preponderance in MENA.

The Biden administration’s policy is that the United States will not intervene in any conflict outside the Indo-Pacific. This unsettles Middle Eastern countries and dents their trust in the US, despite Washington’s strenuous efforts to soothe their concerns.

Notwithstanding supplying regional allies with technical and military resources, the US failure to directly intervene to defend Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates against barrages of missiles and drones by Iran and its proxies changed these countries’ longstanding views of America as a credible ally worth their trust. Their concerns have been further intensified by the Biden administration’s new National Security Strategy pledging to support a more integrated Middle East “while reducing the resource demands the region makes on the United States over the long term.”

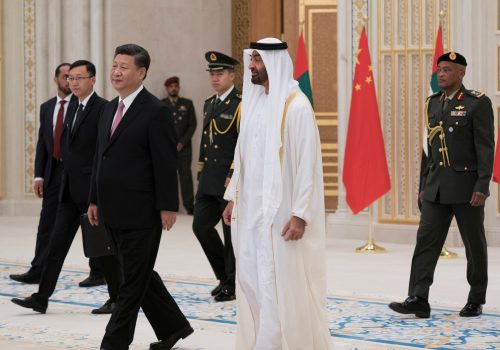

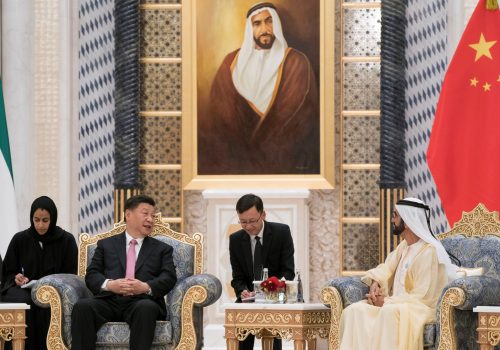

Meanwhile, China has been exploiting the rising skepticism on both sides to advance its interests, which are primarily focused on trade and infrastructure. China’s trade with the Middle East reached $330 billion in 2021. Despite the surge in Russia’s oil supply, Saudi Arabia regained its position as top supplier, with almost 2 million BPD in August and 1.83 million in September. The Middle East received around 57 percent of China’s Belt and Road Initiative investments in the first half of 2022. Middle Eastern countries have also been flooded with Chinese Wing Loong, CH-4, and CH-5 advanced drones due to Washington’s constant rebuffing of their requests to obtain American equivalents.

Rhetoric in China is gradually diversifying to include business development, tech, and, notably, security. Beijing feels more confident in challenging longstanding American wisdom and its regional security role. During Biden’s controversial trip to the region in July, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi was in Syria and used the occasion to take a swipe at American efforts to fix deteriorating ties with Saudi Arabia. After offering support for the region to develop “independently” and end security instability “through unity and self-empowerment,” he accused Americans of interfering and “trying to transform the region by their own standards.”

Three months later, in September, China detailed its vision for a new security order in MENA during the Second Middle East Security Forum in Beijing. The proposal is based on China’s Global Security Initiative (GSI) principles, rolled out by President Xi Jinping at the Boao Forum for Asia in April. Additionally, on October 27, Wang told Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud that Beijing is “taking Saudi Arabia as a priority in its overall diplomacy, its Middle East diplomacy in particular.” The Saudi foreign minister also confirmed Xi would visit his country, putting further restrains on relations with Washington.

China’s GSI is still opaque and it will take Chinese and foreign observers time to decipher its conceptualizing merits. But GSI’s intent, in the MENA context, is pretty straightforward. It aims to export its security and authoritarian policing model and create future momentum to restructure the security order, while fiddling with the concept of cooperative security in a way that would further de-centralize America’s hegemonic position.

To the chagrin of many in Washington, most MENA countries have come to understand and positively interact with both objectives.

This highlights the dilemma of the rising credibility problem that is gripping the MENA perception of Washington’s agenda. China seems one step ahead of US policymakers in realizing its root cause and exploiting Washington’s seeming inability or lack of desire to tackle it head on. It is not surprising then that China will expectedly do more (after the dust of the Communist Party’s twentieth Congress settles) to intensify this dynamic and expedite it.

Besides the shifting security environment and tumbling consensus around US predominance, Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine may have boosted the resolve of Chinese leaders to push regional powers further to seek more strategic autonomy and less US leadership.

The Biden administration’s ill-fated pressure campaign to get Middle Eastern countries to condemn Russian President Vladimir Putin’s obnoxious war has shown that the unipolar moment in the Middle East, like in several other regions, is fading away. One can say that the trend of resisting American policy preferences is on the rise and even overtakes Washington’s and Beijing’s calculations in speed.

A gambling mindset

While cutting oil output by OPEC+ may reveal recklessness and a gambling mindset in dealing with what is seen in Washington as a decisive historical moment, the same assessment goes both ways, as perceptions, whether accurate or false, trigger countries’ behavior and turbocharge unintended geostrategic transformations.

Many analysts, for example, agree that part of Putin’s disastrous decision regarding his move on Ukraine emerged from miscalculation that the US, after its catastrophic drawdown from Afghanistan, was hell-bent on tackling China’s rise and would not intervene in the conflict. This means that rhetoric from Washington focused on containing China and inadvertently ignoring reasserting American commitment elsewhere could have a cataclysmic effect on world security and America’s global standing. In this sense, when the administration treads a course that fuels Middle Eastern perception of US disengagement from the region, it could accidentally set off strategic behavior that is hostile to its interests and, above all, hedging in favor of China and Russia.

Gulf countries’ relations with China are not a luxury or privilege. In addition to generating direct economic benefits, they serve as strategic means to balance China-Iran relations by satisfying China’s economic ambitions in the Gulf and encouraging a comprehensive strategic partnership between Beijing and Tehran that remains low quality. In other words, Gulf countries hate seeing China and Iran get too close to their detriment. Thus far, China’s tacit node to their feelings, coupled with Western economic sanctions on Iran, have indirectly intensified the Gulf countries, especially Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) hedging towards China—Iran relations.

This happens while the White House seems, from the Gulf countries’ perspective, determined to sign a deal to revive the nuclear agreement with Iran while remaining aloof to their strategic concerns. For many in the region, signing another nuclear deal with Iran will be another Afghanistan moment that would further shake trust between the United States and many Arab countries and Israel. This calculation may change if the prospect of Iran obtaining a nuclear bomb becomes real.

In the end, Arab Gulf countries do not want to dodge the bullet of strategic competition with Iran only to find themselves facing a potentially hostile nuclear power at their doorstep. Competing with such a power would not be feasible without building their own nuclear arsenal, triggering a regional nuclear race, and raising the stakes of conflict for both the US and China.

However, for now, following Xi’s consolidation of power for a third term, China will intensify its strategy, deepening distrust in American power in many regions, including the Middle East. The OPEC+ decision to cut oil production, which comes on the back of changing perceptions of the US’s dominant position in the Gulf and Iran nuclear negotiations, creates momentum and encourages China to accelerate the exploitation of the multipolar moment rising in the Middle East.

Ahmed Aboudouh is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter: @AAboudouh.

Further reading

Wed, Feb 23, 2022

China and Russia are proposing a new authoritarian playbook. MENA leaders are watching closely.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

It’s on major Western democracies to make democracy appealing again by aggressively filling the gaps China and Russia exploit to make the world more accommodating to their political models and the new trend of rising authoritarianism.

Thu, Jan 27, 2022

China is trying to create a wedge between the US and Gulf allies. Washington should take note.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Recent events indicate that leaders in Beijing are no longer satisfied with the logic of strategic hedging and are pursuing a more muscular approach to the Gulf.

Thu, Jul 14, 2022

Biden’s Middle East trip focuses on the region. But China is the elephant in the room.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

US President Joe Biden’s visit to the Middle East on 13-16 July won’t directly focus on China. However, the rising power will be the elephant in the room at the Saudi summit in Jeddah.

Image: FILE PHOTO: U.S. President Joe Biden and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman arrive for the family photo during the Jeddah Security and Development Summit (GCC+3) at a hotel in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, July 16, 2022. Mandel Ngan/Pool via REUTERS/File Photo