Should history rethink Paul Bremer’s role in the Iraq war?

In the pantheon of Iraq war “villains,” perhaps no single official has been blamed for more disaster than Paul Bremer, the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) leader who ruled Iraq for roughly one year. Though criticized for wastage and disorganization, Bremer’s tenure is perhaps best known for his two most consequential decisions: the May 16, 2003 purging of Baath party members from the Iraqi government and the May 23, 2003 disbandment of the Iraqi army.

The standard critique is that these decisions were instrumental in plunging Iraq into the abyss of insurgency and civil war. In a stroke, Bremer placed hundreds of thousands of young men with military training out on the street, with no job and a minimal stipend to do nothing. The de-Baathification order also created a cadre of former regime elites with the connections, experience, and political savvy to coordinate resistance to the new American project almost instantly. Indeed, there was good evidence that some of these same regime elites and soldiers wound up helping to generate the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), an existential threat to the Iraqi state.

As Bremer admitted later, the implementation of some of these decisions fared poorly. They were sudden, for one thing. The disbandment of the army shattered public safety and the state at a time when disorder already seemed to be spiraling out of control. The disorder and looting, in fact, was the first real sign that things were going sideways, and Bremer’s decree acted as an accelerant. It was shock and awe—but in the worst way. The evaporation of the army by the time the CPA was installed meant that its de jure disbandment could be seen as an American endorsement of the chaos. Furthermore, there was no clear conception of what came next.

The disbandment was also too broad. While the army was implicated in Saddam Hussein’s regime, different parts of the force, of course, had different levels of culpability. There were many Shia in the army, who would have likely been sympathetic to the new regime and nonpartisan defenders of the new order. As it was, they were out on the street along with Saddam’s loyalists, such as the Republican Guard.

Yet, if there is an argument for Bremer’s decrees, it lies in their sectarianism. Did they harden Sunni rejectionism and fuel the insurgency in Ramadi and Fallujah? Certainly. But the greater good was not their effect on Iraq’s Sunnis, many of whom almost certainly would have been violently hostile to the new Iraq anyway, but on the Shia, as their political leanings were the great unknown of the invasion of Iraq and only slightly less unknown today.

The United States still has little experience with the Shia. Its allies then and now are the Sunnis, and particularly the ultra-orthodox Sunnis of the Persian Gulf. The US’ main experience with the hereditary Arab underclass was a few horrifying episodes of violence in Lebanon two decades earlier. Besides that, with Iran and Iraq walled off and southern Lebanon unwelcoming, there was little contact other than through Iranian-created mouthpieces, and little certainty about how the Iraqi Shia would react to an invasion.

The Shia had no love for Saddam, whose regime had brutally oppressed them and persecuted their faith. But they had little love for the West either. There are long memories in Iraq, and people remember the British installation of Sunnis to rule over their new state, the assumption of power by a Sunni army, and then the ascendancy of a Sunni political party, which was at least a little ironic since the entire point of the Baath party was that it could transcend a Sunni identity. Like the Baath, the army and its officer corps were Sunni institutions committed to keeping Sunnis in power, and many Shia believed that the United States, having deposed Saddam, would follow the British example.

Layered on top of that was the awful experience of a decade earlier when the Iraqi Shia had rebelled against Saddam in the wake of the Gulf War and been suppressed. They had arguably been encouraged in this revolt by President George H. W. Bush and had been abandoned. They would take some convincing that the US was serious.

That they were convinced—that they ultimately supported the new state, or at least did not oppose it en masse—was the great early triumph of the Iraq war, and it was the vital one. The United States could and did fight a war against a vicious Sunni insurgency. But the US could not win a generalized rebellion by the majority Shia, which is what Bremer’s decrees had helped avoid. Had Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani called for expelling the American occupiers, causing some 60 percent of Iraqis to turn their guns on the United States, the US might well have retreated like in Kabul twenty years later, beset by a Pashtun majority.

The US’ Iraq war, at its core, was a sectarian affair. Making Iraq a democracy would by definition mean making it a Shia state, rather than a Sunni or even democratic one. At the time, Washington didn’t see it, and it’s unclear Bremer did either. Rather, the Bush administration’s avowed goal was to build a secular Iraq. But there is an argument that his most famous decrees—however blunt and clumsy—erred on the right side of that divide, and that perhaps helped the United States avoid a larger catastrophe.

Dr. Andrew L. Peek was the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Iraq and Iran at the Department of State from 2017-2019 and is an Atlantic Council nonresident senior fellow.

Further reading

Mon, Jul 26, 2021

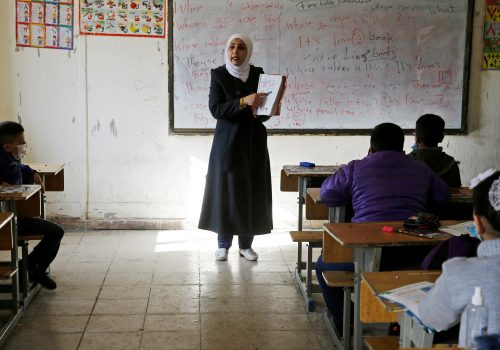

An “illiterate generation”—one of Iraq’s untold pandemic stories

MENASource By

The devastating impacts of COVID-19, coupled with years of spillover effects of violent conflict and extremism, have already proved to be detrimental to students whose education and future career ambitions already receive limited attention.

Fri, Apr 14, 2023

The rise of a Shia Vatican in Iraq

MENASource By

The anchoring of Shia religious institutions as a national actor in the cultural heritage field may altogether change Iraq’s cultural landscape.

Fri, Mar 24, 2023

Black Iraqis have been invisible for a long time. Their vibrant culture and struggle must be recognized.

MENASource By Sarah Zaaimi

Black Iraqis are not only living on the geographical margins of urban agglomerations but also on the margins of society and its structures.

Image: Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, Commander, Joint Task Force Seven, and U.S. Administrator in Iraq Paul Bremmer (R) brief the media in Baghdad on the capture of former leader Saddam Hussein, December 14, 2003. U.S. troops captured an unkempt Hussein hiding "like a rat" in a hole near his home town without a shot being fired on December 13. U.S. President George W. Bush hailed the arrest today as the end of a painful era for Iraq. U.S. forces are holding Saddam at an undisclosed location and hope to extract intelligence on alleged nuclear, chemical and biological weapons which Bush used to justify waging war on Iraq in defiance of many U.N. allies. On the board behind them are images of Saddam before and after (top R) his capture. REUTERS/Steven Pearsall/HO SP/GN