The rise of a Shia Vatican in Iraq

The way the past is used and managed can provide a unique insight into a country’s political trajectory. Since 2003, no one has seen their power and influence change more than that of Iraq’s Shia religious authorities. Indeed, since the early years of the US occupation, attempts to break free from the legacy of dictatorship were pursued by an empowered Shia clerical class, known as the Marja’iya, to ensure that they could become independent. Twenty years on, that goal has now been realized, and the outcomes are transforming Iraq and the landscape of the country’s cultural heritage with it.

Since the establishment of Iraq, the body of the country’s cultural heritage has been informed by US-European interventions and institutions. Iraq’s national museum, the field of archaeology, and the country’s national heritage institution—the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH)—were all established by the West. This institutionalized knowledge dependency was inherited and continues to a large extent to this day.

In recent years, however, an active, organic model of cultural heritage disconnected from Western practice has emerged. It is premised on managing tangible and intangible resources pertaining to Shia Islam. Far too often, culture has not been a priority for international policy. Considering Shia religious Shia authorities’ growing presence and influence in the country, especially regarding how cultural heritage is managed, new research and collaborative relationships must be established.

Today, the Marja’iya—including the Shia Endowment that focuses on managing cultural property and the Shia shrines (Atabaat)—are wielding unrivalled power and resources. The rapid expansion of Shia shrines and commercial properties owned by the Shia Endowment—a state-sanctioned institution—reflects a new, autonomous politics that Shia religious institutions have historically sought to achieve. That ambition had to be quickly realized after the aggressive repression that Shia religious society experienced in the 1980s and 1990s. The religious institution’s multiple, mostly decentralized institutions now control investments in hotels, real estate, private hospitals, universities, factories, and orchards, as well as proceeds from religious tourism.

Thus, a new political economy based around an expansive collection of institutions tied to the Shia clerical class has emerged, effectively representing a state entity within Iraq. Connected to those growing investments, the Shia shrines and Shia Endowment are expanding existing shrines and building hundreds more across the country. This is effectively creating a country-wide grid of cultural and religious sites that contribute to a lucrative Shia pilgrimage and religious tourism network.

The expansion of shrines and the acquisition of territory through investments are gradually transforming entire geographies, repositioned in the service of the Shia religious institutions. This new form of heritage production—the expansion of physical space in the service of Shia religious institutions—has often come at a cost to Iraq’s cultural heritage. Najaf, Karbala, Kadimiyah, and Samarra are now all examples of how the Shia Endowment and shrine authorities have transformed entire neighborhoods to accommodate their plans for growing numbers of pilgrims. This is happening in a context where shrine expansion was highly restricted prior to 2003 by the then Ba’athist state, which tried to limit Shia religious and political activity. In many cases, the usurpation of territory and cultural and religious sites has been characterized by contestation, particularly with the Sunni Endowment. Competition for cultural and religious property between the Shia and Sunni Endowments is an ongoing issue across the country. Over time, the expansion of Shia shrines will influence much of their urban and geographical surroundings.

Shia religious institutions are discovering that, in the context of their increased religious and political prominence and expansion, they have a responsibility to deliver various services, particularly in the field of culture. Indeed, having now secured financial independence, Shia religious institutions can afford to develop and shape large sections of Iraq’s cultural landscape in an image of their choosing. Each of the five main shrines in Karbala, Najaf, Kadimiyah, and Samarra has a de-centralized management structure, meaning that there can be a productive level of competition to ensure the delivery of tangible benefits to their constituents, visitors, and pilgrims. All of the shrines are working toward one goal: the establishment and consolidation of an expansive, inter-connected network of shrines and investments, which constitute a decentralized but nonetheless powerful model of cultural and religious institution.

The Hawza, a collection of Shia religious schools, has historically been a patron and producer of knowledge and writing. Indeed, Hawza’s multiple religious schools and learning centers are active today and comprise thousands of students and learners from Iraq and abroad. However, it is in the cultural heritage field that a glimpse of public-facing initiatives can be seen. Those include the development of heritage museums, such as the Imam Hussein Museum and the Kafeel Museum in Karbala, which possess a significant and growing body of historical collections. Those museums are also working to revive endangered crafts associated with writing, arts, and culture.

Memorialization and the construction of new narratives associated with the past—commonly revolving around notions of Shia suffering and loss—are growing components of these institutions’ work. Libraries, too, containing precious Islamic manuscripts and rare books, have been expanded and new conservation and management systems established, commonly employees working two shifts in any single day. Nowhere in the rest of the country does one see the level of discipline and commitment to work present in the Shia institutions. Indeed, the degree of organization at these institutions and their objective of managing religious and cultural resources are culminating to an Iraqi Shia model of cultural heritage.

The discovery process involved with forming one’s own cultural heritage model has been fraught with trial and error, but experiential learning and the development of best practices and local skills have been encouraged and integrated into all forms of institutional development. Indeed, in a state dominated by political quotas and characterized by post-2003 state dysfunction, the Shia religious authority stands out as a unique hub for organization, discipline, and planning—a world apart from Iraq’s stunted central state institutions that are at the mercy of rapacious political party interests. As a matter of fact, the US occupation’s attempt from 2003 onwards to deconstruct the state of Iraq inadvertently empowered the non-formal state.

An Iraqi Shia model of cultural heritage is, however, a continuing work in progress—albeit one whose results are increasingly visible. It rejects cultural and, by extension, political models premised on Western forms of knowledge and material dependency, though engagement with the world continues through conferences and workshops. Free of predefined and Westernized ways of thinking about cultural heritage, the Shia religious institutions challenge secularized notions of culture that have been the conventional way Iraq’s modern state has dealt with its past.

The resulting cultural heritage landscape, increasingly dominated by Shia religious institutions, will have wide-changing repercussions on Iraq and its political trajectories. However, it is in those spaces that relationships are negotiated and, by extension, institutions that manage society and politics are established. Significantly, and in light of growing interest in Iraq’s cultural heritage, Shia religious institutions need to be better engaged so as not to ignore the work being done to manage Shia-related cultural resources and their long-term impact on the country.

The future of Iraq’s rich and diverse body of non-religious cultural heritage, particularly that managed by the Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Antiquities—which is hugely under-funded and, like other state ministries, traded as an electoral windfall to competing political parties—remains unclear and suffers from weak support from the state. That must change, although successive governments have done little to support this strategic ministry and its multiple institutions, such as SBAH. In the meantime, however, and perhaps for the long-term, the anchoring of Shia religious institutions as a national actor in the cultural heritage field may altogether change Iraq’s cultural landscape. Whether or not emboldened and revitalized religious institutions will transform Iraq, their work may very well accrue to the rise of a Shia Vatican or, at the very least, influence the space in which Iraq’s identities and futures are forged.

Dr. Mehiyar Kathem is an academic and researcher at University College London (UCL) specializing in the politics of heritage and heritage in conflict. Follow him on Twitter: @mehiyar

Further reading

Mon, Jul 26, 2021

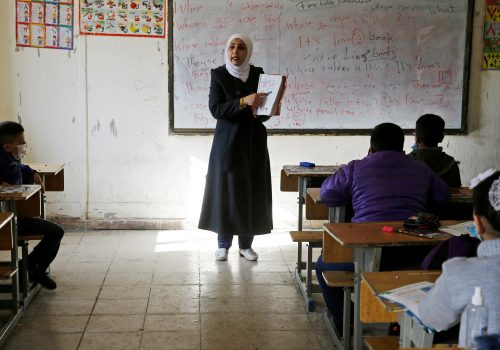

An “illiterate generation”—one of Iraq’s untold pandemic stories

MENASource By

The devastating impacts of COVID-19, coupled with years of spillover effects of violent conflict and extremism, have already proved to be detrimental to students whose education and future career ambitions already receive limited attention.

Fri, Mar 24, 2023

Black Iraqis have been invisible for a long time. Their vibrant culture and struggle must be recognized.

MENASource By Sarah Zaaimi

Black Iraqis are not only living on the geographical margins of urban agglomerations but also on the margins of society and its structures.

Tue, Feb 21, 2023

Iraq needs to address the economy’s structural imbalances to halt the dinar’s volatility

MENASource By Ahmed Tabaqchali

The Iraqi government and the Central Bank of Iraq introduced a series of measures to create domestic demand for the Iraqi dinar and to accelerate the adoption of banking in the economy.

Image: 28 August 2020, Iraq, Baghdad: Shia Muslims take part in a ritual ceremony on the eve of Ashura in front of Al-Kadhimiya Mosque, the shrine of seventh Shia Imam Musa ibn Ja?far al-Kazim. Ashura is a major holy day in Shia Islam that marks the day that Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, was martyred in the 680 AD Battle of Karbala. Photo: Ameer Al Mohammedaw/dpa