The New Middle East is dismissing great power competition—for now

In early October, the thirteen oil-exporting countries composing OPEC+ agreed to cut production to boost oil prices, a decision that may prolong the global energy crisis amid the war in Ukraine. A month and a half after President Joe Biden’s visit to Saudi Arabia and his fist bump with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the announcement was seen as a major setback for the White House.

For some commentators, Saudi Arabia and other Arab monarchies have enjoyed US security guarantees for decades and are now disloyal at a time that many in the West consider a defining moment of international affairs. The frustration is also transpiring in Congress, with senators castigating Riyadh for acting as an “ally of our greatest enemy”—a reference to Russia.

But whether the United States likes it or not, these critics impose a worldview that is not shared in the Middle East. In fact, after reducing the region to the Global War on Terror for two decades, the Middle East is now seen through the lens of the great power competition narrative. This started during the last years of the Donald Trump presidency—well before the Russian invasion of Ukraine—and is now central in the rhetoric of the Biden administration.

Just like the Indo-Pacific, US officials increasingly define the Middle East as a battleground between the United States and China—and, to a lesser extent, Russia. Beijing’s forays into the port infrastructures and the digital networks of US partners in the region like Israel and Gulf states give credence to the narrative.

However, this great power matrix is misleading, as it dismisses the agency of local actors. Middle East states are seeking more and more not to align themselves along the lines of great power competition, but rather want to use the competition for leverage to satisfy their interests. For instance, the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) February 25 abstention vote on the first United Nations security council resolution on the Ukraine war did not mean that Abu Dhabi sided with Russia. Rather, the Gulf state narrowly followed its national interests, giving greater importance to a UN resolution on Yemen passed three days later, which condemned the Houthi rebels and for which Russian support was essential.

Most importantly, this ambivalence of US Middle Eastern partners reflects new regional dynamics from within. For the past two years, the Middle East turned—perhaps temporarily—the chapter of the great rivalry between two blocs—one led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE and the other led by Qatar and Turkey. After the 2011 Arab uprisings, that competition took the contours of a cold war, with both blocs pushing for their interest across the region.

Since 2021, all parties have worked towards de-escalation—partly out of their realization that US disengagement from the region implied that they had to take matters into their own hands. After the Gulf states put an end to the Qatar blockade in January 2021, a frenzy of diplomatic visits followed to display the warming of ties. That momentum for de-escalation even involved Iran. Riyadh and Abu Dhabi toned down their hawkish rhetoric towards Tehran and showed their intention to restore ties with the regime. This sometimes contradicted US policy. For instance, in July, a day after President Biden reaffirmed his determination to prevent a nuclear Iran and called for a Middle East air defense alliance to counter Tehran, UAE presidential adviser Anwar Gargash retorted that his country was “not part of any axis against Iran.”

This de-escalation momentum coincided with the signing of the Abraham Accords in 2020 and the subsequent wave of normalization between Israel and several Arab states. Although the accords were sometimes met with skepticism in the West, they reflect the new foreign policy ambitions of Middle Eastern countries.

Since the agreement, the level of overt, public engagement between Israel and Arab states has been unprecedented; from joint naval drills in the Red Sea to free-trade agreements, these countries have indicated their determination to go beyond mere recognition. True, the Abraham Accords do not solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—two Gaza wars occurred since its signing—but they do not consider its settlement as a precondition to developing Israel-Arab relations. This de facto challenges the logic of previous diplomatic plans from the Oslo Accords to the 2002 Arab League Peace Plan. In March, Israel hosted a Security Summit in the Negev attended by Bahraini, Emirati, and Egyptian foreign ministers and is expected to become a regular forum. The summit again illustrates how much the Middle East landscape has changed in only two years.

Noticeably, these developments came from the region and not from the outside. True, we don’t know yet if dynamics like reconciliation among regional players and normalization with Israel will last, and if they can truly coincide with one another. But they evidence the growing desire of Middle Eastern states to shape the regional order on their own terms.

Ultimately, both trends signal their aspirations towards strategic autonomy. As one Abu Dhabi-based advisor boasted to me, “this is the coming-of-age moment for UAE foreign policy.” However, that autonomy is far from being achieved. In the military domain, US partners still rely heavily on Washington’s support and it remains to be seen if local diplomatic initiatives like the Negev Summit can deliver on regional issues. But, overall, the trend towards Middle Eastern strategic autonomy is here to stay and will likely increase if the US reduces its presence from the region.

So how does this new Middle East impact US regional interests? The diversification of foreign policies by US Gulf partners is unlikely to match all Western expectations. But that is also the case with the foreign policy of India or Israel. Seen from the Gulf, Washington should not expect partners to stand idle when it pursues policies not in line with Middle East states’ own preferences.

Consequently, if the US truly wants to increase its focus on China and Russia—as clearly stated in the latest National Security Strategy—it needs to better define its acceptance threshold, such as the minimal conditions required to preserve US interests in this new Middle East. Surely, the fight against terrorist organizations—in particular al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS)—as well as the prevention of nuclear proliferation across the region, will remain essential objectives and should be clearly conveyed to allies and partners.

But the United States is unlikely to compel Middle Eastern partners with its great power narrative. Gulf states, as well as Israel, consider China too essential for their economic prosperity to side against Beijing. Chan Heng Chee, a former Singapore Ambassador to the US, once stated, “don’t press countries in the region to choose. You may not like what you will hear”. The statement was meant in a Southeast Asian context, but it also resonates with today’s Middle East.

At the same time, Washington should encourage intra-regional initiatives—with or without US involvement—that may de-escalate tensions. New minilateral formats like the Negev Summit, or I2U2 (India, Israel, the UAE, and US) create what Biden’s National Security Strategy calls a “latticework” of partnerships. This could give texture to a security architecture that has long been missing in the region. It might also alleviate US efforts to prevent a future regional crisis. Rather than imposing a cold war narrative and forcing local partners to abide by its rules, the best way for Washington to tamp down the Middle East from becoming a focal point of competition with China or Russia is to encourage such local initiatives. The more local actors grow confident about their own autonomy, the less tempted they will be to align themselves on the agenda of another external power.

Jean-Loup Samaan is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council. He is also a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute of the National University of Singapore. Follow him on Twitter: @JeanLoupSamaan.

Further reading

Tue, Aug 16, 2022

Under Macron’s leadership, France is leading a middle power strategy in the Gulf. Here’s how.

MENASource By Jean-Loup Samaan

France is positioning itself as a Western partner that, although may not be a substitute to Washington, is one that provides a “convenient and credible” option to those Gulf leaders eager to diversify their partnerships.

Thu, Jan 27, 2022

China is trying to create a wedge between the US and Gulf allies. Washington should take note.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Recent events indicate that leaders in Beijing are no longer satisfied with the logic of strategic hedging and are pursuing a more muscular approach to the Gulf.

Mon, May 23, 2022

Until Israel deals with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it can’t lead in the region

MENASource By

The normalization momentum launched by the Abraham Accords could finally lead the Jewish State to not just co-exist with its Arab neighbors, but participate alongside those countries in defining the terms of a regional security architecture. It’s in the interests of Israel and the United States to achieve that goal.

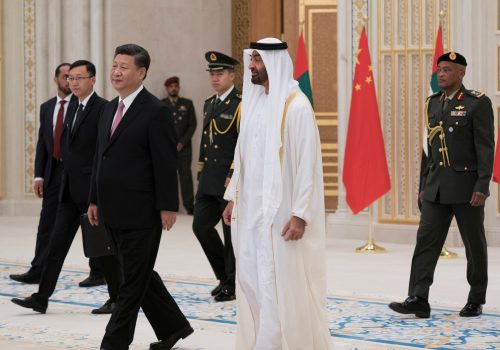

Image: FILE PHOTO: Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and U.S. President Joe Biden meet at Al Salman Palace upon his arrival in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, July 15, 2022. Bandar Algaloud/Courtesy of Saudi Royal Court/Handout via REUTERS