Want resiliency in MENA? Invest in women-led startups

As more people get vaccinated, the world cautiously begins to see a light at the end of the coronavirus tunnel, but with few thinking that it is possible to return to the world left behind in February 2020. Most see the pandemic as a powerful tipping point and a wake-up call to build back better on multiple fronts, such as narrowing inequalities and improving sustainability to ensure more resiliency vis-à-vis future shocks. This undoubtedly requires innovation across many domains.

In the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA), women could play a transformational role. First, they make up a large share of the talent pool in most MENA countries, which remains largely underutilized. According to UNESCO, they outnumber men in universities and make up to 57 percent of all STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) graduates. This rate exceeds the 35 percent share of women studying in STEM fields in the United States and European Union. However, only one in five women are economically active. Second, International Monetary Fund (IMF) studies show a causation between women’s labor force participation and a country’s economic diversification in terms of the range and sophistication of industrial output and exports. Third, the GDP of MENA countries is estimated to rise 30-40 percent if women are better integrated into the economy. Capitalizing on such significant growth potential would increase resiliency and the ability of governments to meet current shocks and any future ones.

A growing body of evidence shows that the lockdowns impacted women from an economic perspective disproportionately worse than men. The World Economic Forum finds that “[W]omen make up 39 percent of global employment but account for 54 percent of overall job losses.” In the US, for instance, some five million women have been impacted in one way or the other. In MENA, it is in the order of 1.5 million—around eight hundred thousand in Iran and seven hundred thousand in the rest of MENA. This is a steep decline given the region’s far lower female economic participation rates prior to the pandemic.

In normal times, women perform an average of 75 percent of the world’s total—largely unpaid—care work. In MENA, this figure goes up to 80 or 90 percent. Closures of schools and care facilities resulted in an increased workload at home, forcing many women globally to downshift or quit altogether to reconcile work and family duties. Perhaps the silver lining of the economic setbacks for women has been the widespread appreciation for the “care infrastructure.” The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that implementing family-friendly policies could reverse COVID-19’s regressive effects on working women and yield an additional $13 trillion to the global economy by 2030.

“Care” has moved from a pre-pandemic negligence within the policy realm to a must-do urgency that underpins the workings of other sectors. Its centrality to bolstering social resiliency in the rest of the economy is now widely acknowledged. For this reason, the “care economy” has been integrated into the newly announced US infrastructure/jobs proposal. Care is viewed as an essential building block for the future economy, just like roads and bridges, broadband, and high-speed trains.

At the policy level, nearly all pandemic fiscal stimulus packages in diverse countries have paid special attention to the impact on women, and the recent World Bank/IMF Spring Meetings focused in part on this topic. In MENA, Egypt was the first country to have a COVID relief program. “There were twenty-one policies related specifically to women and included corresponding trackers,” according to Rania al-Mashat, Egypt’s International Cooperation Minister. And, at the family level, the pandemic may have also helped dislodge some of the deep-rooted social norms about the gendered division of labor, as husbands and fathers had to roll up their sleeves and help with household chores. For instance, when a Lebanese minister remarked, “let women cook a little bit” on Sundays—a day when restaurants were closed due to lockdown—in November 2020, Lebanese men objected to the sexist comments by flooding social media with proud pictures of them doing the cooking.

What can be done?

Increasing female economic participation could entail: supporting sectors that are relatively more women-intensive/friendly; bridging the gender digital divide, since access to the internet proved so critical during lockdowns and will certainly prevail here on after; and last but not least, improving the environment for women-led startups to spur innovation and job creation.

The good news is that overall, the ecosystem for entrepreneurship in the region has improved. According to the 2020 MIT Enterprise Forum Pan Arab Impact Report, there has been a steady rise in startups in the region and women seem to be largely driving this growth. Nearly one-third of the increase was in Saudi Arabia following legal reforms to broaden women’s economic opportunities.

Legal reforms are important but the availability of finance is even more critical. Prior to the pandemic, the MENA region experienced a welcome growth of venture capital. In 2019, funding exceeded $700 million for over 560 investments and, in 2020, the amount was expected to exceed $1 billion. While this is an improvement, there is still a long way to go as it represents only a small fraction of the region’s GDP and what is required to spur innovation. Post-lockdown trends indicate that the region may remain an attractive investment space and, therefore, venture capital should continue to increase in the coming years.

Still, women-led startups face a dearth of early-stage funding, which limits their potential. This is a global challenge and not specific to MENA. For instance, in the US, where female founders account for about 36 percent of all American entrepreneurs, startups by women only received a mere 2 percent of the $130 billion of all startup investments in 2018. It rose to 12 percent in startups with at least one female founder. While data for women-only startups in MENA are not available, those with at least one female founder received 11 percent of funding in 2018, which is similar to US averages. This is a good start but still considerably short of where it could be.

Nadine Mezher of the Dubai-based investment advisory platform Sarwa attributes the funding shortage to bias: “Women get more push backs during pitches and get judged on performance while men are judged on potential.” Her assessment is consistent with London Business School’s Dana Kanze, whose 2010-2016 cross-country field study confirmed the link between funding and gender bias during pitches. Kanze found that investors pose to men “promotion-focused” questions and ask women “prevention-focused” queries. Hence, men have a better chance to explain the upside of their ideas, while women must spend their valuable pitch minutes on how they would mitigate the downside. This suggests that investors prejudge that women are more likely to fail and hence pose higher risk.

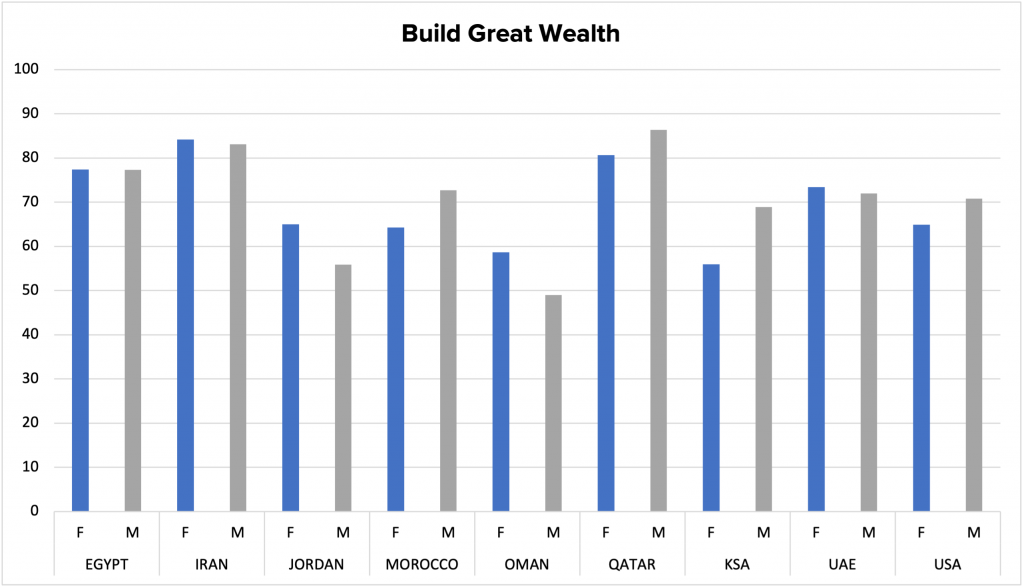

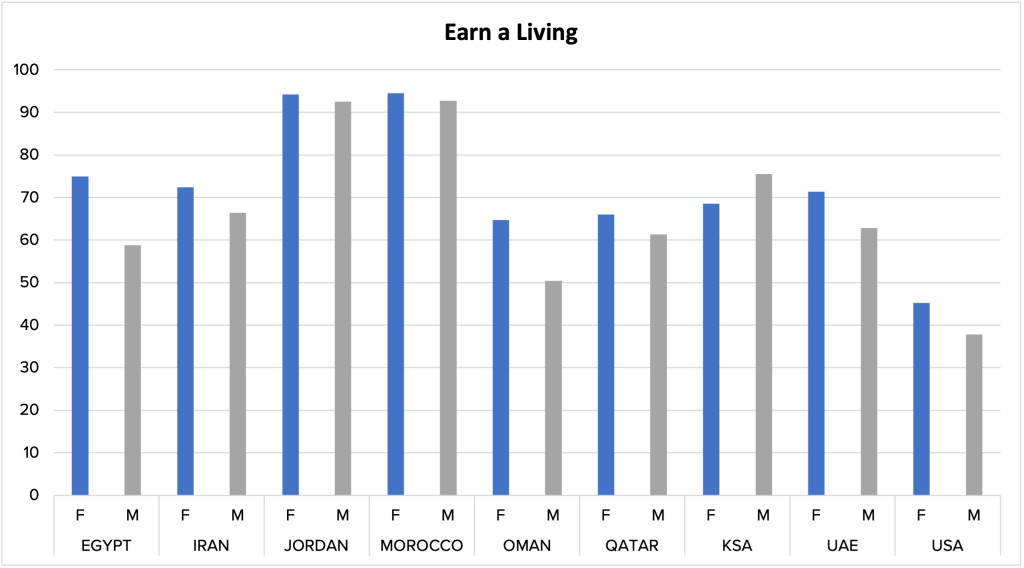

The bias may originate from the belief that women are less profit-driven and more interested in humanitarian causes. Yet, data from the 2020 GEM Report proves the opposite. In MENA countries, for instance, women entrepreneurs expect to “build great wealth” and “earn a living” as much as their male counterparts (see figure). This is essential data for funders who want to make money and obtain high returns. Moreover, a Boston Consultancy Group study found that, globally, “despite funding disparity, startups founded and cofounded by women actually performed better over time, generating 10 percent more in cumulative revenues over a five-year period.” Other studies confirm similar trends and results.

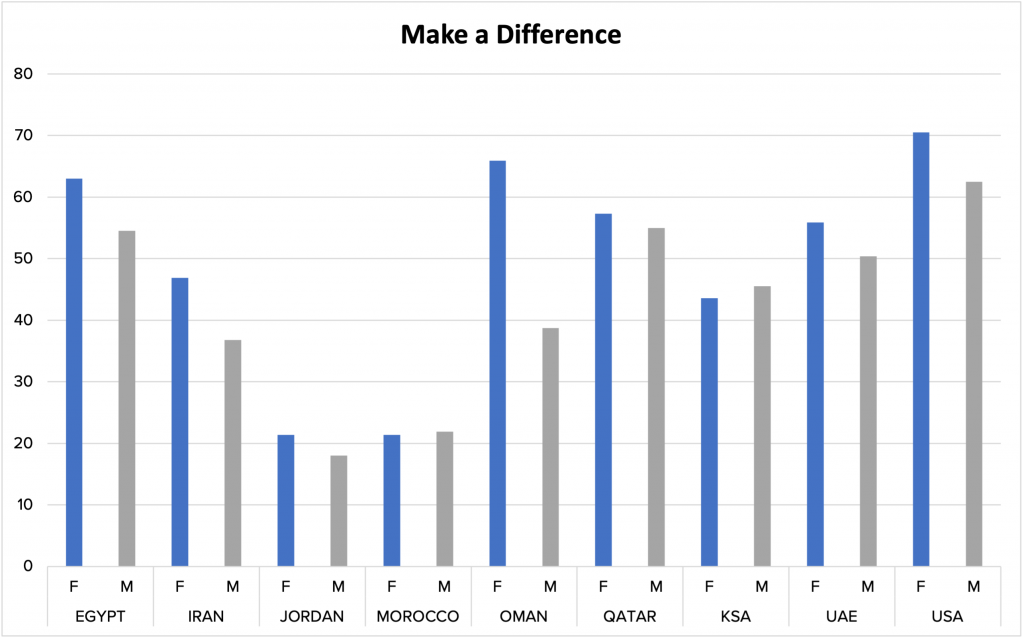

In terms of wanting to “make a difference” through their businesses, yes, women’s responses exceed those of men in most countries, and so do they in MENA. This may indicate that these businesses meet their customers’ needs better and it could well be the secret to the staying power of the impressive sample of current women entrepreneurs in MENA, who have grown their businesses despite prevailing gender-based barriers. As such, women-led businesses strive to be financially lucrative and socially impactful. They are precisely the kind of post-pandemic economic activities that countries need.

Another reason for the shortage of funding for women-led startups is unconscious bias since venture capital investors are mostly men. “As humans, our intuition leads us to choose what mirrors us and what we see as familiar,” says Mezher of Sarwa. “This is what is happening here and it is more enhanced in the region for cultural reasons, even though we have more women venturing into entrepreneurship.” A positive trend in recent years is that more and more women have become venture capital (VC) investors or made it to the C-suites of VC firms. More women in leadership can certainly add to the diversity of decision-making and enrich perspectives.

An increasing number of women will likely become angel or VC investors because of the considerable assets owned by women in the region. A possible indicator of such potential is the gap between the forecasted regional annual GDP growth of 2.1 percent in the coming years versus the 8.5 percent-projected yearly rise of the MENA luxury goods market until 2025, which is largely targeted towards women. So, there is ample disposable funds. Perhaps some of these resources can be diverted away from consumption and into funding innovation, given that the number of women VC and angel investors is on the rise globally.

Conclusion

As MENA assesses how to rebuild better after the pandemic, women-led startups could be part of the solution. The rising percentage of female tertiary education, particularly in STEM fields, and the dearth of jobs has led many young women to strike out on their own. The coronavirus crisis has accelerated widespread digital use across sectors, which has opened new business opportunities. Recent reports suggest a rising regional trend of female startups—as much as one in four—which will add diversity in the startup realm and establish positive role models for societies. Capitalizing on the potential of women-led startups will also increase resiliency and the ability to meet current and future shocks. However, women still face difficulties in obtaining early-stage funding due to a host of implicit bias and structural challenges, and governments could do more to dismantle barriers and promote women’s entrepreneurship as well as funding for women-led ventures.

Nadereh Chamlou is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and was formerly a senior advisor to the chief economist at the World Bank’s MENA Region. Follow her on Twitter: @nchamlou.

empowerME at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East is shaping solutions to empower entrepreneurs, women, and the private sector and building influential coalitions to drive regional economic integration, prosperity, and job creation.

Image: Young entrepreneurs work on their laptops at the Amman-based Oasis 500, a seed investment firm which finances start-up firms in the region's information technology sector, November 2, 2011. REUTERS/Muhammad Hamed