Even as the US-China trade war proceeds to the next gripping chapter, another trade drama is unfolding between the Trump administration and the US Congress on the fate of the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) as a replacement to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The administration missed the opportunity to obtain Congressional approval for USMCA prior to the August break, and House Democrats’ insistence that there be key changes to the agreement before it is taken up remains a central dynamic in its future prospects.

All of this is highly reminiscent of the circumstances that prevailed over twelve years ago when the George W. Bush administration prepared to bring several pending free trade agreements (FTAs) to the Congress under “fast-track” legislation that was in place at the time. Just like today, the US House of Representatives in 2007 had recently switched from Republican to Democratic control in the midterms that took place in November 2006. And just like today, Democratic votes were critical to winning passage for several FTAs that were pending then—with South Korea, Panama, and Peru. Yes, and just like today, House Democrats then sought changes to these pending FTAs in their provisions on labor, environment, and intellectual property protections for pharmaceutical products.

Prior to 2007, there had been circumstances in which members of Congress sought accommodations from the administration in power in exchange for their votes on FTAs. In fact, the hard-fought battle to pass NAFTA in 1993 turned critically on the new Bill Clinton administration negotiating side agreements on labor and environment. But 2007 was very different, with Democrats insisting that their proposals be incorporated directly in the text of the agreements through renegotiation. The Bush administration recognized that it had no choice but to reach a deal with House Democrats if it were to avoid humiliating defeats of legislation to pass the agreements or alternatively avoid putting them on the shelf for a future administration to take up under new fast track authority.

Over a period of several months during the spring of 2007, senior officials of the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) trudged up to the Hill on a daily basis to sketch out a detailed set of changes to the agreements in the areas of labor, environment, and intellectual property rights for pharmaceuticals. The White House and USTR leadership instructed senior career officials to be accommodating even though some of the proposed changes involved fundamental upheavals to approaches that had been negotiated in previous FTAs, such as those with Australia, Central America, Chile, and Singapore. Examples included substantial broadening of provisions for settling disputes between parties on labor and environmental matters and rolling back enhanced protections for US pharmaceutical companies in provisions on intellectual property rights. On May 10, 2007, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Ways and Means Chairman Charles Rangel (D-NY) announced with great fanfare that they had reached agreement with the Bush administration on a package of changes—what later became known in trade circles as the “May 10 Deal.”

The perspectives of the affected trading partners seemed to be little more than an afterthought. Negotiating teams from USTR went to them to communicate that these changes would need to be incorporated into their agreement prior to US Congressional consideration and that these countries effectively had no choice in the matter—a true take-it-or-leave-it scenario. This stance was most sensitive with South Korea, which was not inclined to swallow changes without a fight. A small team of USTR negotiators were on a plane to Seoul days later to obtain these changes and smooth highly ruffled feathers.

Back to the present, USTR officials and House Democrat trade staff are using the August break to attempt to reach a deal on the areas of labor, environment, intellectual property rights for pharmaceuticals, and enforcement. In many respects, the discussions on enforcement appear to be focused on implementation of labor provisions by Mexico in the USMCA, just as special arrangements on enforcement of provisions on illegal logging for Peru were included in the May 10 deal. It also appears that USTR is seeking to be accommodating in its efforts to reach agreement with House Democrats so that it will be in a position to discuss any necessary changes to the USMCA with Mexico and Canada by September and then proceed with submission of legislation to the Congress to bring the agreement into force with enough Democrats on board in the House to obtain passage.

Assuming this all comes to pass, the Trump administration will have accomplished its first substantial success for its trade negotiation agenda by borrowing a page from the book written by the Bush administration in 2007. And even though this victory may be a more Pyrrhic one than a truly transformational one, given that the USMCA will replace a NAFTA that has been viewed by most trade experts as a success more than twenty-five years after it came into force, it can nevertheless set a standard that proves to be an enduring one. The specifics of a new deal between the Trump administration and House Democrats are likely to serve as a template in the areas of labor, environment, intellectual property rights for pharmaceuticals, and enforcement for future negotiations, just as the May 10 deal became the template for the FTA negotiations that followed it. In the end, the date will have changed but the political realities remain much the same.

Mark Linscott is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center. He served as the assistant US trade representative (USTR) for South and Central Asian Affairs from December 2016 to December 2018. He previously served as the assistant US Trade Representative for WTO and Multilateral Affairs from 2012 to 2016 with responsibility for coordinating US trade policies in the WTO.

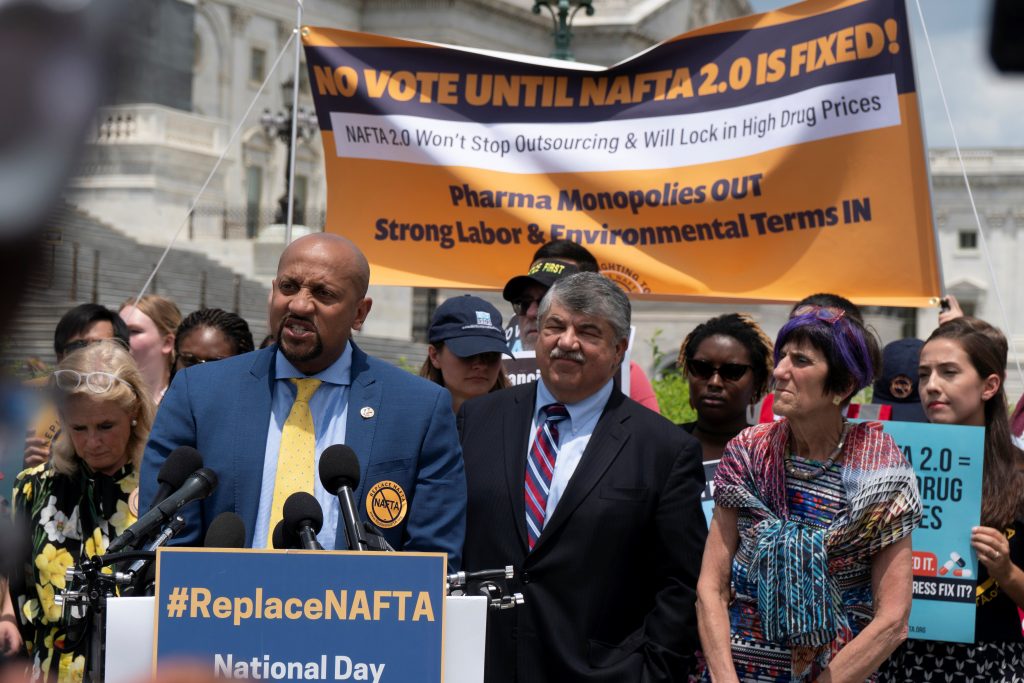

Image: Hasan Solomon, legislative director of International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, speaks as Richard Trumka (C), president of the AFL-CIO and U.S. Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) look on, at a rally outside the U.S. Capitol, asking for changes to the United States-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) trade agreement, in Washington, DC, U.S., June 25, 2019. Picture taken on June 25, 2019. REUTERS/Jonas Ekblom