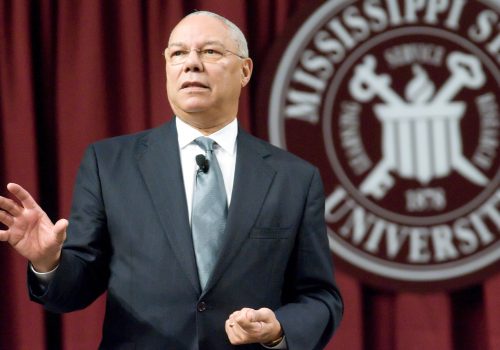

Celebrating the remarkable life of General Colin Powell

On Monday, October 18, at the age of eighty-four, General Colin Powell passed away from COVID-19 complications amid a battle with multiple myeloma and Parkinson’s disease.

For Powell, it was a struggle against a determined enemy that couldn’t be defeated by his usual weapons of strategic logic, remarkable charm, engaging humor, and powerful empathy for those who face the greatest challenges with the most optimism.

Powell was an Atlantic Council honorary board director, a recipient of our 2005 Distinguished International Leadership Award, the first Black secretary of state, the first Black chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the first Black national security advisor, and a friend to many at the Atlantic Council. He was a personal friend and adviser.

Ahead of his memorial service on Friday at the National Cathedral, I wanted to share four ways that he profoundly impacted the Atlantic Council and will continue to do so.

First, he helped galvanize our commitment to next-generation leadership training; second, his so-called “Powell Doctrine” (often misrepresented) of “decisiveness” informs the work we do on US strategy; third, at a time when we are so focused on diversity and equity, his life’s lessons are all the more powerful; finally, his “Thirteen Rules to Live By” are an excellent recipe for our Atlantic Council culture, which has long held that optimism drives outcomes.

1. Next-generation leadership: Toward the end of a lengthy chat I had with General Powell in the study of his home, he cut off yet another one of my questions on world affairs.

“You know, I spend less time these days thinking about geopolitics and more time preparing the next generation of leaders,” he said. “I can’t predict what might happen in the world in the years ahead, but I do know that we are going to need a very special group of young leaders who are equipped with the character and capabilities to deal with this challenging world.”

His commitment to serving future generations was concentrated most in his work with the Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership at the City College of New York.

That said, he also inspired the Atlantic Council to build out its next-generation efforts on three fronts: our Millennium Leadership Program, our Young Global Professionals paid internship program, and the mentoring of our own staff, 65 percent of whom are under thirty-five years of age.

2. The “Powell Doctrine” of decisiveness: General Powell was complimented and bemused to have a doctrine named for him, though he was never quite sure how that happened.

The Powell Doctrine, which exists in no military manual, emerged in late 1990 after President George H.W. Bush, on the recommendation of Powell and General Norman Schwarzkopf, “decided to double the force facing the Iraqis,” Powell writes in his memoir. “It reflected my belief in using all the force necessary to achieve the kind of decisive and successful result that we achieved in the invasion of Panama and in Operation Desert Storm.”

Commentators have reduced the Powell Doctrine to one of “overwhelming force,” but Powell writes, “I have always preferred the term ‘decisive’ (to ‘overwhelming’). A force that achieves a decisive result does not necessarily have to be overwhelming…It’s the successful outcome that’s important, not how thoroughly you can bury your adversary or enemy.”

3. Diversity and racism: Powell’s impact on race-related issues has been considerable, but it has less to do with what he wrote or said and more to do with the power of his example.

The Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan tells General Powell’s story from the 1950s as a soldier in the South, where he could buy whatever he wanted at Woolworth’s in Columbus, Georgia, but couldn’t eat there. He could spend his money at any department store in town, so long as he didn’t try to use the men’s room.

He considered the military of that time “the most democratic institution in America.” So, he wrote, “nothing that happened off-post, none of the indignities, none of the injustices, was going to inhibit my performance…I did not feel inferior, and I was not going to let anybody make me believe I was…Racism was not just a black problem. It was America’s problem. And until the country solved it, I was not going to let bigotry make me a victim instead of being a full human being.”

The story he most liked to tell about overcoming adversity took place during President George W. Bush’s first state visit to Great Britain in 2003. Condi Rice, then-White House National Security Advisor, was in a Buckingham Palace sitting room with then-Secretary of State Powell and his wife Alma.

As Noonan writes:

“It was very grand, the women in gowns, Colin in white tie and tails. Talk turned to the past. Condi and Mrs. Powell were daughters of the segregated South, raised in Birmingham, Ala. In 1963, when the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed by white supremacists, Condi, blocks away in her home, heard the blast and learned that a little girl she played dolls with had been murdered, along with three others. Alma’s father had been principal of the largest black high school in Birmingham, and her uncle principal at the second-largest, where Condi’s father had been a guidance counselor. Colin, raised in the South Bronx, had served in the South in the 1950s, and knew Birmingham from courting Alma.

Now here they were in a palace. They drank a toast to their ancestors. ‘They never would have believed it,’ Condi said. No, said Colin, ‘but they are smiling right now.’”

4. The Thirteen Rules: And that brings me to Powell’s Thirteen Rules—not quite the Ten Commandments or even Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses, as they were merely scribbled aphorisms collected on snippets of paper under the glass cover over his desk.

Still, they ended up in Parade magazine and as the first chapter in Powell’s book, It Worked for Me: In Life and Leadership. They are all about the power of optimism. Here is an edited version:

- It ain’t as bad as you think. It will look better in the morning. I have always tried to keep my confidence and optimism up, no matter how difficult the situation…Leaving the office at night with a winning attitude…conveys that attitude to your followers. It strengthens their resolve to believe we can solve any problem.

- Get mad, then get over it. Everyone gets mad. It’s a natural and healthy emotion…[but] staying mad isn’t useful…With a few lapses I won’t discuss here, I’ve done reasonably well.

- Avoid having your ego so close to your position that when your position falls, your ego goes with it. In short, accept that your position was faulty, not your ego.

- It can be done. Have a positive and enthusiastic approach to every task.

- Be careful what you choose: You may get it. Don’t rush into things…Usually there is time to examine the choices, turn them over, look at them in the light of day and darkness of night, and think through the consequences.

- Don’t let adverse facts stand in the way of a good decision. Superior leadership is often a matter of superb instinct.

- You can’t make someone else’s choices. You shouldn’t let someone else make yours. Since ultimate responsibility is yours, make sure the choice is yours and you are not responding to the pressure and desire of others.

- Check small things. Success ultimately rests on small things, lots of small things. Leaders have to have a feel for small things—a feel for what is going on in the depths of an organization where small things reside.

- Share credit. When something goes well, make sure you share the credit down and around the whole organization…People need recognition and a sense of worth as much as they need food and water.

- Remain calm. Be kind. Few people make sound or sustainable decisions in an atmosphere of chaos…Calmness protects order, ensures we consider all the possibilities, restores order where it breaks down, and keeps people from shouting over each other.

- Have a vision. Be demanding. Followers need to know where their leaders are taking them and for what purpose. Purpose is the destination of a vision…It should be positive and powerful, and serve the better angels of an organization.

- Don’t take counsel of your fears or naysayers. Naysayers are everywhere…Their fear and cynicism move nothing forward. They kill progress. How many cynics built empires, great cities, or powerful corporations?

- Perpetual optimism is a force multiplier. Perpetual optimism, believing in yourself, believing in your purpose, believing you will prevail, and demonstrating passion and confidence is a force multiplier. If you believe and have prepared your followers, the followers will believe.

From serving two formative tours in Vietnam to advising four presidents through some of the most consequential moments of the last four decades, General Powell both witnessed and made history. Throughout his remarkable career, General Powell distinguished himself as a dedicated and principled leader, and he was an inspiration to many around the world.

An Atlanticist at heart, General Powell was a proponent of international alliances and an advocate of NATO. He observed firsthand the Alliance’s success in competing with the Soviet Union during the Cold War and believed that it would continue to play a crucial role in responding to the challenges of the twenty-first century—albeit while also recognizing that the Alliance would need to change and adapt first.

He clearly expressed this view during a 2009 interview I conducted with him on the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, when I asked him what concerned him most about the future.

“I am worried about the instability we see manifested in places like Iraq, Afghanistan, North Korea, and Iran,” he said. “I think the Alliance has a role to play in dealing with these kinds of issues. I am deeply concerned about poverty throughout the world. I am concerned about infectious diseases…The Atlantic Community would do well to redirect more of its energies to these issues.”

In 2005, we presented him with the Distinguished International Leadership Award. As he accepted his award that evening, General Powell said, “America needs to make sure that it never allows the transatlantic link to weaken; it is the surest guarantee of the movement toward peace and freedom.”

We welcomed him back in 2011 to introduce Distinguished Artistic Leadership Award honoree Plácido Domingo, in 2012 to introduce Distinguished Humanitarian Leadership Award honoree HRH Prince Harry of Wales, and once again in 2014 to introduce Distinguished Military Leadership Award honoree General Joseph F. Dunford, Jr.

One of my most memorable exchanges with him came when I asked him whether he preferred to be called General Powell or Secretary Powell. “That’s an easy one,” he said. “General Powell. I earned that one.” He had unflinching and passionate respect for military service and, in particular, for those who served the United States in uniform.

General Powell’s legacy and contributions to the United States will continue to inspire future leaders and generations. And they will continue to inspire the Atlantic Council as we, in the words of General Powell, advance our “noble work that is [never] finished.”

Frederick Kempe is the president and CEO of the Atlantic Council.

Further reading

Tue, Oct 26, 2021

How Colin Powell was ahead of his time

New Atlanticist By Andrew L. Peek

The Powell Doctrine would have been more at home in the next Republican administration than his own.

Fri, Oct 22, 2021

Colin Powell’s glorious American journey

New Atlanticist By Harlan Ullman

As a gentleman, Powell treated all people with great respect—no matter their rank or status.

Mon, Oct 18, 2021

The Powell Doctrine’s wisdom must live on

New Atlanticist By Christopher Preble

Colin Powell’s criteria governing the use of force abroad aimed to ensure that war is always a last resort. US leaders shouldn't forget that as they honor his legacy.

Image: FILE PHOTO: Former U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell salutes the audience as he takes the stage at the Washington Ideas Forum in Washington, September 30, 2015. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst