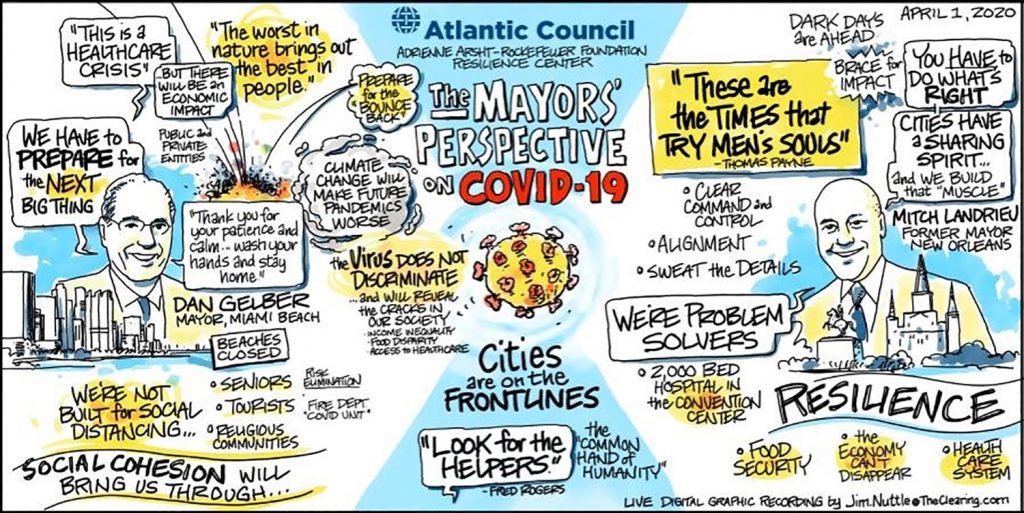

As the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic worsens and deaths increase around the world, national and local governments are racing to prepare their healthcare systems, infrastructure, and economies to weather the current storm. “The world writ large was not adequately prepared to see what has come,” former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu said on April 1, adding that now it is up to mayors and local officials who “are really on the front lines,” to take action to protect their citizens.

“We walked into this with both arms tied behind our back,” according to Mayor of Miami Beach Dan Gelber, who joined Landrieu for a virtual event with the Atlantic Council on April 1. The long incubation period of the virus, which can take weeks to begin triggering symptoms and can be transmitted by people who never show signs of infection, means that government officials are responding to statistics that only show an accurate picture of the virus from two or three weeks ago. This lack of information and mixed messages from federal and global health authorities about the status of the outbreak left mayors and other officials “feeling like we had to [respond] ourselves,” Gelber argued.

He explained that initial guidance from the US Centers of Disease Control to cancel public gatherings of fifty or more people simply didn’t fit his specific city, which is full of mixed commercial-residential space and large senior communities. “We are not a city built for social distancing,” he said, which forced him to quickly adopt a stay at home order to try to limit the spread.

Landrieu explained that the immediate emergency response to the virus is “being led by the mayors of America on the ground in partnership with their governors and attempted partnership with the federal government.” Mayors and other local government officials are best equipped to deal with the crisis, he argued because they “are the people who are closest to the ground” and are often “the most in coordination with each other because they know what is happening in their respective jurisdictions.”

These local officials, however, are dependent on “clear command and control between and amongst the different levels of government,” especially state and federal agencies, Landrieu added. He warned that when these different levels of government are not on the same page “you will always have a failure along the way and more people will suffer rather than less.” He cited the current scramble by states to secure ventilators to help prevent COVID-19 deaths as an example of state and federal officials not in complete alignment. “You can feel that we are out of sync today,” he said.

Despite the initial start, Landrieu was confident that coordination would become stronger, as in the recent decision by authorities to use the New Orleans Convention Center to provide 2,000 additional hospital beds for the city. Cooperation between mayors and local officials also remains strong, he said, as “mayors are in constant coordination” and often “have license to steal from each other” when it comes to solutions to managing the crisis.

Both Landrieu and Gelber also stressed that the federal government will need to help cities manage the emergency. “Cities and states are going to have to get money from the federal government…to sustain the employees that they need,” including police officers, firefighters, and essential services providers, Landrieu said. Gelber acknowledged that he was disappointed that the recent federal stimulus package passed by Congress did not include support for cities with less than 500,000 people. He pointed out that while Miami Beach has only 95,000 residents “we have 10 to 15 million annual visitors,” which makes it a vital engine for the region’s economy.

Local officials will also need to take time to prepare for the future, once the immediate needs of the emergency are met. “While we are looking down, fighting hard…we have to take a minute to look up,” Landrieu argued. “We still have to be prepared for other things” that might hit later such as natural disasters or other crises. Cities will need to “refocus our attention on what resilience really means” after the experience of this virus, he said.

Moments like this crisis are when “our failures are revealed to the world,” Gelber added, conceding that “a lot of the things we needed to do on the front end were not done,” partly because of the failure to seriously consider threats “that are just imagined.” Going forward, he continued, government officials at all levels should focus on “getting all of the private and public entities and infrastructure prepared for this kind of thing.”

But both Landrieu and Gelber maintained that the attention of all mayors will remain focused on the current emergency. As older populations are more at risk of death from the virus, Gelber said that for “our general population we are in risk management. In our senior population we are in risk elimination,” and officials are working to ensure food and basic services delivery to this population while limiting their exposure. In a crisis as severe as this, Gelber said, “you have to sweat the details.”

“We have to…brace for impact,” over the coming days, Landrieu warned. “Over the next two weeks in the United States of America, [it] is going to be hard to imagine how difficult the consequences will be.” Although he was confident that the crisis will eventually be overcome, “our country has not received a blow like [what is coming] in our lifetimes,” he said. While focus remains on preventing as much pain as possible, he added, citizens and societies around the world must also be ready to learn from this emergency and emerge on the other side stronger than before.

David A. Wemer is associate director, editorial at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

Further reading:

Image: A New York Police officer stands guard in an almost empty Times Square during the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in New York City, U.S., March 31, 2020 REUTERS/Eduardo Munoz