Dispatch from Odesa: Russia escalates its naval war against Ukraine

In recent days, the front line of Moscow’s aggression against Ukraine appears to have shifted south toward the Black Sea—placing major port cities such as Mykolaiv and Odesa directly in the crosshairs of a Russian naval buildup that began just before its full-scale invasion in February 2022.

While exact numbers are difficult to come by, the bulk of recent missile strikes on Ukrainian targets such as Odesa have originated in the Black Sea. One estimate put the Russian amphibious assault ship increase at the start of the full-scale invasion as equivalent of an additional one-and-a-half battalion tactical groups. Earlier this week, Russia carried out a live fire “exercise” against potential maritime targets in the northwestern part of the sea.

Russia’s daily strikes on Ukrainian targets along the Black Sea coast represent an extraordinary escalation. They mark a shift in Russian strategy toward leveraging missile batteries in occupied Crimea with Kh-22 and P-800 Oniks anti-ship cruise missiles, which typically fly at extremely high speed and, as they reach their targets, can descend to low altitude (as low as thirty-two feet) along the water or land, making them difficult to intercept.

Some residents here in Odesa have responded by heading to safer ground in the countryside or overseas, but for the most part I’m detecting the same irrepressible resilience that was on display in the earlier months of the war.

While it’s doubtful Russia plans to decimate Odesa to the extent that it laid waste to Mariupol, the force with which it is pounding the southern port region has folks here worrying. After all, in one night alone, Russian forces launched at least thirty cruise missiles, primarily from ships in the Black Sea, according to the Ukrainian Air Force. One strike came dangerously close to the Chinese consulate and damaged a wall of the building. Some residents here in Odesa have responded by heading to safer ground in the countryside or overseas, but for the most part I’m detecting the same irrepressible resilience that was on display in the earlier months of the war.

The Kremlin has significantly escalated tensions after torpedoing the Black Sea Grain Initiative on Monday, attacking Odesa port infrastructure and then issuing a unilateral declaration from the Russian Ministry of Defense that all Black Sea vessels sailing to Ukrainian ports will be considered potential carriers of military cargo. The statement added that no matter which flags the vessels carry, they would be considered on Kyiv’s side.

If there are any lingering doubts about the lengths Russia will go to choke off Ukraine’s agricultural exports, just read the words of RT editor-in-chief and Kremlin propagandist Margarita Simonyan: “All our hope is in a famine… The famine will start now, and they will lift the sanctions and be friends with us, because they will realize it is necessary.”

The Ukrainian Defense Ministry said in a Telegram post on Thursday that the move “deliberately creates a military threat on trade routes, and the Kremlin has turned the Black Sea into a danger zone.”

In a savvy retaliatory move, Ukraine’s defense ministry shot back with its own announcement that, starting July 21, it, too, will begin to consider all Russia-bound vessels as carrying military cargo. Kyiv also declared the northeastern part of the Black Sea a closed military area. That could potentially make it more expensive—if not impossible—for commercial ships bound for Russian ports, such as major oil exporting harbor Novorossiysk, to obtain insurance.

A wild card in all of this is Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, one of the few NATO leaders able to speed dial both Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. While Erdoğan was unable to salvage the grain deal, he does have the ability to turn up the heat on Putin by, for example, insisting that ships sailing to and from Russia have sufficient insurance coverage. A few weeks back, Turkey made life difficult for Russian and Belarusian airlines by suspending the provision of refueling and servicing of their Boeing and Airbus aircraft at Turkish airports. Erdoğan and Putin are reportedly scheduled to meet in person in August.

Russian friends in the Middle East and Africa, such as Egypt, which relies heavily on Ukrainian grain imports, need to further step up pressure on Moscow to reopen commercial shipping lanes across the Black Sea. Ethiopia, the host country to the African Union, received almost 300,000 tons of food from Ukraine under the grain initiative—and another 90,000 tons of grain as part of a separate initiative, Zelenskyy said. Ethiopia is one of seven countries in East Africa experiencing unprecedented levels of food insecurity, according to the World Food Program. South Africa and the African Union can help stave off further hunger on the continent with sanctions against Russia should Moscow continue to blockade food exports from Ukraine.

Meanwhile, on land, at the northern end of a 620-mile front line, Russia has been quietly amassing 100,000 soldiers at the Lyman-Kupiansk axis, according to Serhii Cherevatyi, spokesman for the Eastern Group of Ukraine’s armed forces. Cherevatyi said that the manpower buildup is almost equal to the 120,000 troops Moscow had deployed to Afghanistan during the height of Soviet invasion in 1979-1989. The Russian soldiers are reportedly being backed up with 900 tanks, 555 artillery systems and 370 multiple launch rocket systems.

With two of Odesa’s main industries seriously hampered—the port and the tourism and hospitality sector—it is unclear how much longer Ukraine’s jewel on the Black Sea coast can endure Russia’s onslaught without stronger support from Western allies. Now that Russia has crossed yet another red line with the targeting of infrastructure crucial to the global food supply chain, Western capitals need to counter Russian aggression with fresh responses—including the deployment of armed flotillas to escort commercial ships carrying agriculture products from Ukrainian ports or providing significantly more Patriot missile batteries that can intercept incoming Russian cruise missiles.

At the end of the day the question needs to be asked: Why is it that a small group of men in the Kremlin get to decide the fate of hundreds of millions of people around the world and whether they have food on their plates?

Michael Bociurkiw is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center.

Further reading

Mon, Jul 17, 2023

Russia just quit a grain deal critical to global food supply. What happens now?

New Atlanticist By

The last ship under the UN- and Turkey-brokered deal to export grain and fertilizer from Ukraine by sea has left Odesa. Atlantic Council experts explain what to expect next.

Tue, Jul 18, 2023

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was never about NATO

UkraineAlert By Peter Dickinson

Putin's relaxed response to the NATO accession of Finland and Sweden proves that he knows NATO enlargement poses no security threat to Russia but has used the issue as a smokescreen for the invasion of Ukraine, writes Peter Dickinson.

Thu, Jul 20, 2023

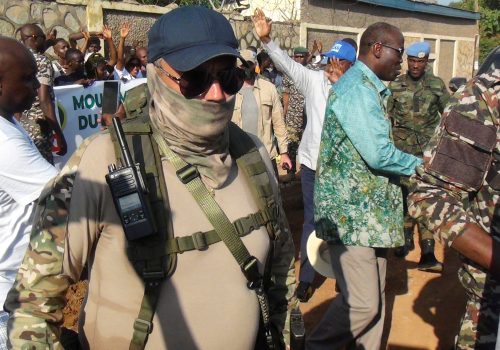

Russian War Report: Wagner is still in business in Africa

New Atlanticist By

Despite their Russia-based forces being relocated to Belarus after their failed mutiny, Wagner Group is still alive and active in Africa, including ahead of a referendum in the Central African Republic.