Amid the escalating war in Ukraine, some US legislators and former officials have sounded the alarm about Russia using cryptocurrencies to evade American sanctions. In reality, though, Moscow’s abilities to do so are more limited and illusory than they might initially appear.

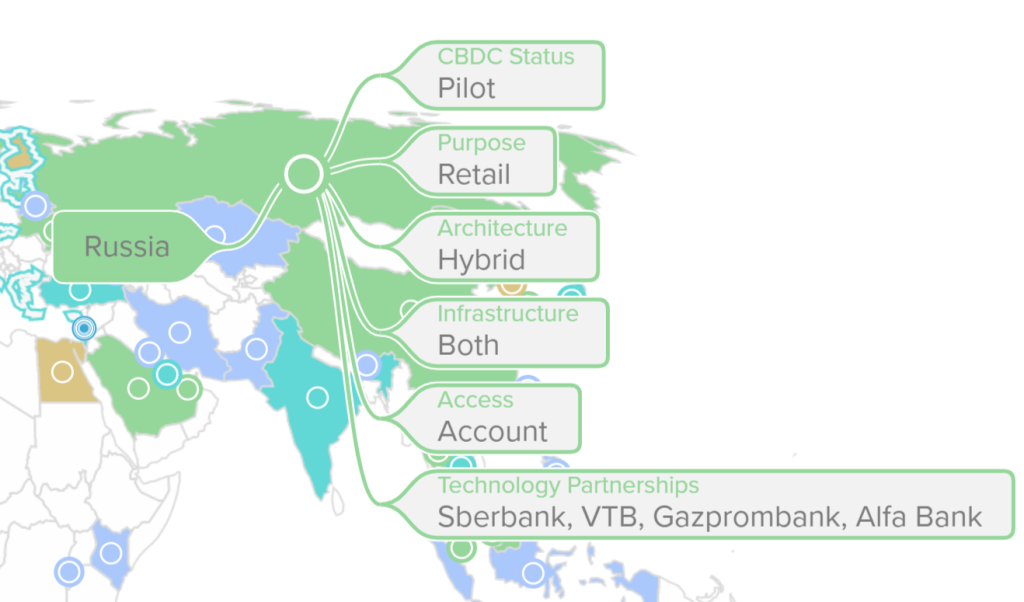

On Tuesday, the New York Times reported that Moscow’s proposed new “digital ruble” would leave Russia “better able to resist sanctions.” Globally, more than ninety central banks are exploring state-backed digital currencies, known as CBDCs (which the Atlantic Council has been tracking for more than two years). However, the Council’s study reveals several reasons why a digital ruble would not actually be an immediate or easy means of skirting US policy—starting with the fact that a Russian CBDC does not actually exist yet, beyond a limited pilot program for domestic use announced just two weeks ago. It typically takes years to design, decide on, develop, and deploy massive new financial technology like this.

In theory, Russia could use its digital tender to trade directly with other nations without using the dollar as an intermediary currency. That, however, is easier said than done: Internationally, it is unclear why any nation would want large sums of digital rubles on its balance sheet anytime soon. Questions also remain about how widely accepted a digital ruble would be within Russia—particularly since it would experience much of the same volatility and counter-party limitations as the regular ruble in the face of sanctions.

Some members of Congress have suggested that privately issued cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, could serve as a shelter for sizable Russian assets going forward. Again, that’s unlikely.

Contrary to popular belief, American companies offering cryptocurrency exchange services already must comply with US law, including foreign-asset restrictions and anti-money-laundering programs. Larger companies have heavyweight in-house lawyers who have spent years as federal prosecutors and take these compliance issues seriously.

Even logistically speaking, it would be difficult to try to use cryptocurrency to sidestep sanctions at scale (a fact the US National Security Council’s director for cybersecurity confirmed this morning). For one, the US Justice Department and Internal Revenue Service (to say nothing of the intelligence community) are increasingly skilled at tracing complex transactions on public blockchains, as evidenced by the recent indictment involving a $4.5 billion conspiracy to launder stolen cryptocurrency. Additionally, the Bank of Russia would need vast amounts of cryptocurrency—around $400 billion—to counteract sanctions that target its foreign reserves. That’s larger than the total market cap of all but two cryptocurrencies and, in the case of Bitcoin, would require massive purchases which would likely lead to price spikes (making evasion more and more expensive).

Politically, Moscow’s attitude toward decentralized cryptocurrency has been mixed—precisely because the Kremlin cannot control it. In the last month, Russia’s central bank has called for a full ban on cryptocurrencies, whereas its Finance Ministry introduced a draft bill that would license and regulate them. True, Russia-based ransomware gangs often use cryptocurrency as a means of receiving payment from victims; but even if the Kremlin boosted that as a revenue generation device, it’s hard to see how roughly $600 million in ransom per year could compensate for hundreds in billions in frozen assets and stymied transactions.

In the United States, some cryptocurrency executives are objecting to demands for a blanket ban on all Russian civilian users out of stated concerns about individual economic freedom, humanitarian implications, or other kinds of fallout. Whether or not one agrees with them, the ability to advocate for different federal policies is a feature—not a bug—of living in a democratic nation.

Even before Russia’s attack on Ukraine, there was regulatory flux in the United States about digital assets and how to balance various policy concerns, including national security and privacy. The invasion will complicate these questions even more; an AP report suggests that the Biden administration is mulling a “focused tactical strategy” to choke off cryptocurrencies as a medium that the Kremlin can use to bypass sanctions.

Meanwhile, the Ukrainian government has officially called for Bitcoin and Ethereum donations to support resistance efforts, which have already amassed $22 million and are expected to grow. The takeaway: Decentralized, instant payment methods—much like paper cash—can be used both for good and ill.

All told, Washington should avoid alarmist domestic regulations based on the mere possibility, likely chimeric, of what the Kremlin might do with cryptocurrencies. Clearly, Russian President Vladimir Putin now has an even greater incentive to find alternatives to the international financial system, in addition to his decade-long goal of de-dollarizaton. But cryptocurrencies won’t save the Kremlin, and Moscow is more likely to turn to expanding gold reserves or a parallel system to SWIFT; it already has a nascent financial transactions network of its own, and could collaborate with China on Beijing’s equivalent system. That’s where Washington needs to pay attention next.

JP Schnapper-Casteras is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and a practicing attorney.

Further reading

Sun, Feb 27, 2022

Ukraine has finally prompted the West to shift course on Putin

Inflection Points By Frederick Kempe

The Zelenskyy delegation’s chance to succeed in talks at the Belarus border with a Russian delegation would be far greater if Putin were confident that the West has Ukraine’s back.

Tue, Mar 1, 2022

Four ways the war in Ukraine might end

New Atlanticist By Barry Pavel, Peter Engelke, Jeffrey Cimmino

The United States, its transatlantic allies and partners, and the entire world face a difficult period of sustained contestation with Russia.

Wed, Mar 2, 2022

State of the Union: Lessons from Biden’s moves on Russia and the US economy

New Atlanticist By

Our experts weigh in on the key questions raised by US President Joe Biden's hour-long address.

Image: This image shows a sign outside a Sberbank branch in Russia. Photo by Vyacheslav Prokofyev/TASS via REUTERS