Countering Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and keeping Chinese global influence in check is rightfully dominating the national-security agenda in Washington. But what about North Korea—whose saber-rattling continued to vex the Beltway long before Russia stole its attention? While the recently shifted world order hasn’t changed the nature of the threat from Pyongyang, it’s still imperative for Washington to stay committed to its investments in deterrence and interdiction to ensure that North Korea does not take aggressive action against South Korea, Japan, or even the US homeland.

Following the Donald Trump administration’s courting of North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un and suspension of essential US-South Korean joint military exercises, Washington is now entering a period of much-needed correction. Much of that involves recalibrating expectations for US reliability and presence, reinvigorating security ties with Seoul, and staying ahead of the North Korean missile threat.

Pyongyang’s rapid and dangerous increase in testing short-, medium- and even long-range ballistic missiles this year—while possibly readying for a seventh nuclear test later this year—are not new North Korean bargaining tactics. Neither are its attempts to secure a higher and more urgent place on the US national-security threat matrix; the regime must stay high on that matrix if it wants to maintain global relevance and secure concessions from the United States.

North Korea is not any stronger than in the past, but with renewed protection from China and Russia, it does have more space to act recklessly and spark confrontation. It has launched at least eighteen ballistic missiles this year alone, including its first test in March of an intercontinental ballistic missile since 2017. Two months later, just after US President Joe Biden’s first presidential trip to Asia, North Korea fired three missiles. And in early June, days after the USS Ronald Reagan concluded a three-day naval exercise with South Korea, North Korea launched eight more.

The Biden administration and Congress are both acting in a responsible and deliberative manner to strengthen deterrence against North Korea. Strategically, the administration’s February 2022 “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States” rightfully calls for advancing integrated deterrence and working with Congress to fund the Pacific Deterrence Initiative to deter aggression and counter coercion. The Department of Defense’s (DoD) March 2022 National Defense Strategy prioritizes, among other elements, defending the homeland and deterring strategic attacks against the United States. While North Korea is not the leading threat in the strategy, it is nevertheless a prominent side show for defense planners.

The White House has also reversed the slide in funding for missile-defense spending that occurred during the Trump administration. Funding is up to ten billion dollars in Fiscal Year 2022 for the DoD’s Missile Defense Agency (MDA); this will ensure adequate and sustainable funding for new Next Generation Interceptors and associated radars and sensors, which are vital for deterring North Korea from launching ballistic missiles toward the United States. The DoD is expected to deploy twenty Next Generation Interceptors starting in 2028, and the MDA has reportedly already set four critical flight tests as part of its commitment to “fly before you buy” principles. The rigorous testing effort and ultimate deployments will further strengthen the credibility of US deterrence because North Korea will have less confidence that a launch against the homeland will be successful.

The political repair job needed in Asia to counter the North Korean threat is also underway. In May, Biden and new South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol met in Seoul and agreed to resume robust joint military exercises. These exercises are more than symbolic, as they demonstrate readiness, foster unity of purpose, and signal the strength of this key strategic alliance. They also encourage vital closer trilateral cooperation among the United States, Japan, and South Korea on countering North Korean provocations—and, even more broadly, signal to China that the United States is not conceding its presence in Northeast Asia.

Yet North Korea does not seem prepared to change course. In April, Kim Jong Un announced his intent to “strengthen and develop” Pyongyang’s nuclear forces at the “highest possible” speed. Today, the country also has far more room to be provocative because China and Russia are in an open adversarial competition with the United States for leadership in the Indo-Pacific. For Beijing, at least, it is a useful lever to pull when regional instability serves its interests in that competition. It could, for example, give Pyongyang tacit approval to engage in sea-based incursions of Japanese or South Korean territorial waters to pull US attention from deterring Chinese aggression against Taiwan. Moscow, too, could threaten to export advanced missile technologies to North Korea if Washington fails to ease some sanctions or stop sending weapons to Ukraine.

To be sure, there are limits to how much North Korea can further destabilize the region and credibly threaten the United States. It has indeed already established that it can develop nuclear weapons and possesses the ability to launch long-range missiles at the United States; Pyongyang also is improving the range, reliability, and volume of its missile and nuclear-weapons complex. But this ability to threaten the United States has existed for nearly ten years—and adding more offensive capacity does not alter the fundamental balance of power, since the United States is adding more defensive capacity.

So where does this leave the Biden administration? In a sense, back to the future: It has all but re-adopted the Obama-Bush-Clinton approach of attempting to negotiate an end to North Korea’s nuclear and long-range missile programs through inducements, threats, and punishment. For its part, North Korea has shown no meaningful movement toward giving up its strategic arsenal. The negotiating situation has been stagnant for an entire generation.

Given the near-certainty of North Korea refining its long-range missile arsenal and its nuclear-weapons complex, the United States must invest in tools that greatly reduce North Korean threats to the homeland. But long-range missiles are just one element of deterrence. US adversaries are increasingly developing hypersonic and cruise missile capabilities—technologies that make these projectile increasingly fast and maneuverable. Investments now in enhancing missile detection and interdiction capacity are fundamental to making sure the United States is not held hostage to North Korea and likeminded regimes.

It will be critical for the Biden administration’s budget to continue to reflect capabilities needed to address both homeland and regional threats. It must ensure policymakers are adequately funding the MDA, given the agency’s increasing demands. The United States no longer has the luxury of prioritizing homeland over regional affairs, or vice versa. It needs credible defenses against the likes of both North Korea and China.

The good news is that the Biden administration and Congress are both moving in the right direction—but they should also not lose focus on the longer-term strategy. Staying ahead of the qualitative and quantitative missile threat North Korea poses to the homeland is vital to US national defense.

Todd Rosenblum is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and served as acting assistant secretary for homeland defense at the Pentagon from 2011-2015.

Further reading

Thu, Jul 28, 2022

Climbing the escalation ladder in Ukraine: A menu of options for the West

New Atlanticist By Francis Shin, Damir Marusic, Tyson Wetzel

Our experts have assembled a list of possible policy responses the West ought to consider if Russia escalates its war against Ukraine.

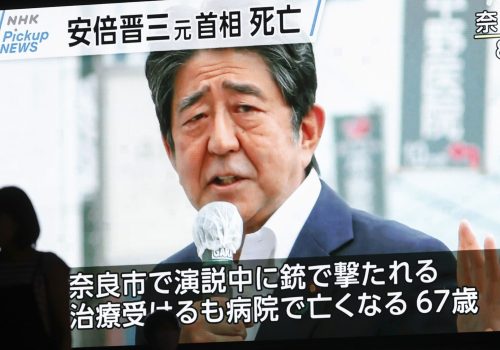

Fri, Jul 8, 2022

Shinzo Abe’s murder has shocked the world. What legacy will he leave behind?

New Atlanticist By

Experts from the Council’s Asia Security Initiative weigh in on what Abe’s death means for Japan’s future.

Thu, Jul 28, 2022

Former US Defense Secretary Esper’s five-point plan for Taiwan to deter China

Event Recap By Katherine Walla

The island must “make the first move” in shoring up its defenses and protecting its national security, said former US Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper at the Atlantic Council.

Image: The South Korean and US militaries fired eight combined surface-to-surface missiles ATACMS into the East Sea in response to North Korea multiple ballistic missile launches on June 6, 2022. Photo by SOUTH KOREA MND/EYEPRESS/REUTERS