China’s growing ambition to recode the rules of cyberspace should serve as a wake-up call for the Indo-Pacific’s leading digital democracies: Cooperate on technology or risk ceding ground to Beijing and its expanding digital sphere of influence.

At the historic Quad summit held in March, leaders of the United States, Japan, India, and Australia took important steps to bolster tech cooperation. Foremost among these efforts was the creation of a new Quad working group on critical and emerging technologies, which will drive coordination on standards, encourage diversification of equipment suppliers and future telecommunications technology (particularly 5G), and convene regular dialogues on critical-technology supply chains. Although China was not specifically referenced in this context, the cause célèbre is quite clear: anxiety about China’s growing digital adventurism.

While the unity on display at the Quad summit was an impressive show of strength, it was also an incomplete picture that masked growing friction among members on several elemental technology issues such as cross-border data flows, data privacy, payments, digital taxation, competition, e-commerce, and law enforcement.

For its part, India has pointedly rejected Japan’s “data free flow with trust” formulation for cross-border data transfers and championed expansive data-localization restrictions through its forthcoming data-privacy legislation. The United States has frequently clashed with India on digital-trade and online-freedom issues and has taken steps to levy tariffs on New Delhi in response to the Modi government’s digital taxes. More recently, Australia has engaged in a high-stakes showdown with US social-media companies over its “pay-for-news” law, which resulted in Facebook temporarily pulling all news content from its platform in Australia.

For the national-security community, it may be tempting to sideline these digital-trade battles as commercial irritants that distract from cooperation on strategic-technology issues. Yet this would be a mistake. If the Quad is to reach its full potential in technology cooperation, its members must find ways to tap into the full power of the private sector.

To see why, consider how strategic-technology innovation takes place in the modern era. Efforts to develop strategic-technology capabilities today are less Manhattan Project than Menlo Park; private-sector firms big and small, rather than governments, push the boundaries of innovation and develop technologies with commercial applications and a strategic valence. Innovations in dual-use technologies such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and advanced robotics are important examples; they emerge from commercial imperatives, but they produce national-security applications that deliver strategic benefits.

Pure market dynamics can also create and amplify strategic risks to Quad members. The concerns over TikTok’s global growth are a case in point. While the app’s privacy approach allows invasive collection of data at the individual level, its global popularity magnifies the scale and impact of those risks and gives them salience as a national-security threat. If Quad policymakers accept that TikTok or other Chinese firms pose strategic risk, then the need to check their growth and market share should follow logically.

Over the past four years, members of the Quad have understood this imperative and sought to curb the growth of Chinese firms using policy instruments. New Delhi has banned TikTok and nearly 270 other Chinese apps. The United States, Australia, Japan, and India have all either formally banned Huawei or excluded the company from participating in 5G trials. Restrictions on inbound Chinese foreign direct investment and outbound investment in Chinese firms are also starting to take root among Quad members, especially India and the United States.

Though bans and investment restrictions are powerful, they are limited in scope. Countering a “Digital Sinosphere” on a global basis will require getting the world’s netizens to choose non-Chinese platforms at scale.

This is fundamentally a question about competition and power in the global digital economy. And here, the strategic imperatives facing the Quad collide with the economic goals and sensitivities of individual members. Quad countries agree on the need to find alternatives to Chinese platforms, but they also want their own firms to reap the commercial benefits of displacing Chinese companies. This is especially true in India—home to the most internet users of any democracy—where leaders are seeking to build up a domestic tech ecosystem that breaks reliance not just on Chinese platforms but also on US companies such as Amazon or Facebook that hold significant market share in e-commerce, payments, and messaging.

There are no simple solutions to resolve these tensions. But the way forward requires the Quad and its leaders to think expansively about technology cooperation and be more attuned to digital-trade challenges that are generating friction among members. While the Quad countries have not collectively engaged in dialogue on these issues, past bilateral agreements could provide a starting point. Still, collaboration won’t be easy.

Three of the partners—Australia, Japan, and the United States—have long histories of cooperation and negotiation on tech issues. In 1998, the United States and Japan penned a joint statement of principles governing electronic commerce. These included provisions on data flows, protection, and privacy. Each of the three has signed a bilateral free-trade agreement with the others (although the Japan-United States deal is a “Phase 1” agreement) that includes more extensive provisions on electronic commerce and digital trade. All three of these countries are also participating actively in “plurilateral” negotiations in the World Trade Organization (WTO).

India, on the other hand, has no similar bilateral agreements in place. Its free-trade agreement with Japan has an annex on telecommunications services, although it deals primarily with public telecommunications networks, interconnection, and other market-access issues. Perhaps the most striking example of disagreement among the Quad is that India has actively objected to WTO negotiations. Along with South Africa, India argues that these negotiations and others like them violate WTO rules and principles by not involving all members, even as it refuses to participate.

Thus, the starting point for Quad cooperation should be modest and realistic, seeking incremental outcomes but with some sense of urgency given the high stakes. We offer the following recommendations:

- A strong first step would be expanding the scope of the Quad working group on critical and emerging technologies to cover the wide array of digital issues, including data governance and law-enforcement cooperation. More broadly, a Quad economic dialogue led by foreign ministers and trade ministers could also serve as a useful forum to drive greater alignment on critical digital issues such as cross-border data flows, data protection, and digital commerce.

- This group could focus this initial work on surveying existing digital agreements between individual Quad partners, recognizing that most do not include India. India should have an opportunity to express its views on these approaches and how they might differ from its emergent regulatory policies.

- The next step should involve a Quad effort to develop a set of principles on digital-trade governance. This could be an iterative process that evolves over time: core principles, updated and elaborated principles in specific areas such as data flows and data privacy, and eventually a full-blown framework of Quad principles on digital trade.

- The group should interact with CEOs of leading tech companies from each country, which would create opportunities to align on thorny digital issues and help build common solutions to shared concerns.

We are convinced that the Quad should be a critical forum for advancing a united front on digital issues, and that resolving the commercial tensions among member countries can unlock the full strategic benefits of this partnership. Pursuing convergence on commercial digital issues is vital to countering Beijing’s Digital Sinosphere. In the post-COVID-19 era, the need for greater cooperation between government and corporate technology leaders has never been more clear.

Mark Linscott is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center. Prior to joining the Atlantic Council, he was the assistant US trade representative for South and Central Asian Affairs from December 2016 to December 2018 and assistant US trade representative for WTO and Multilateral Affairs from 2012 to 2016.

Anand Raghuraman is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center and a vice president at The Asia Group, where he advises leading companies operating in South Asia across the internet, e-commerce, social-media, fintech, and financial-services sectors.

The South Asia Center is the hub for the Atlantic Council’s analysis of the political, social, geographical, and cultural diversity of the region. At the intersection of South Asia and its geopolitics, SAC cultivates dialogue to shape policy and forge ties between the region and the global community.

Further reading

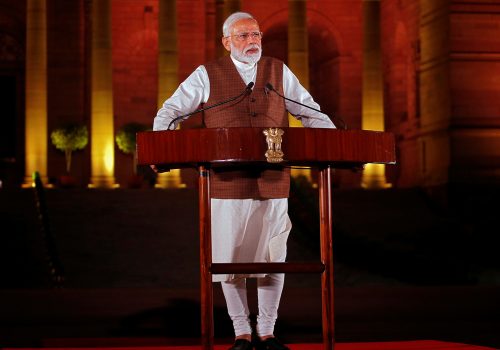

Image: President Joe Biden, joined by Vice President Kamala Harris and Secretary of State Antony Blinken, participates in a virtual Quad Summit with the leaders of India, Japan, and Australia on Friday, March 12, 2021, in the State Dining Room of the White House. (Official White House Photo by Adam Schultz via Sipa USA and Reuters.)