US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s July 6-9 visit to China went smoothly, following a well-choreographed script. But the ability of Yellen’s visit to achieve its goal of cooling tensions between the two superpowers will be limited, as Yellen’s statements were premised on two flawed assumptions about the nature of US-China relations.

First, while criticizing China’s unfair economic practices, Yellen also encouraged economic engagement, as well as cooperation in addressing global problems such as climate change and low-income countries’ debt burdens. Yellen’s attempts to compartmentalize areas of cooperation between the two countries will fall flat, as Chinese policymakers do not bracket off China’s economic relationship with the United States from their political disputes with Washington.

Second, Yellen defended measures to restrict China’s access to US advanced technology as necessary for national security. She said the United States aimed to de-risk but not decouple from China and did not intend to constrain China’s growth. This framing will not assuage Beijing’s concerns, as Chinese officials see both de-risking and decoupling as efforts to hinder China’s economic growth. Thus, Yellen’s Beijing visit will not meaningfully improve US-Chinese relations, as the two nations’ core interests remain at odds with each other.

Can compartmentalization work?

The United States has recently enacted measures to control the supply to China of high-tech products and know-how in advanced semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing to safeguard US national security. Yellen suggested that China should not let this stop the two countries from engaging in trade and investment “based on fair rules” for mutual benefit or from collaborating on other global cooperative initiatives. Yellen has employed the compartmentalization approach: trying to promote an economic relationship with China on a separate track from the countries’ rivalries in the political sphere.

Compartmentalization reflects more wishful thinking than realism when it comes to dealing with China, which, since the twentieth National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in October 2022, has emphasized a holistic approach to national security. That approach encompasses perceived threats to military, diplomatic, political, social, economic, and development interests, which necessitate “all of government” and “all of society” efforts to respond. In fact, China has long used economic coercion to achieve its political goals—demonstrating that Chinese policymakers view trade and politics as linked rather than compartmentalized.

In this context, the more the United States and China engage in tit-for-tat measures in the name of national security, the more those steps will deepen mutual mistrust, coloring relationships in other areas and making compromises more difficult to reach. Appeals to focus on areas of cooperation for mutual benefit sound reasonable, but will ultimately be futile in changing the nature of the US-China rivalry as a whole.

De-risking vs. decoupling

Yellen also adopted the terminology introduced by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, stressing that the United States aims to de-risk but not to decouple from the Chinese economy. Yellen was emphatic: Decoupling from China “would be disastrous for both countries and destabilizing for the world… and virtually impossible to undertake.” By contrast, de-risking means “diversification of critical supply chains or taking targeted national security actions.”

The distinction between de-risking and decoupling seems to have some basis in fact. US-China economic interactions in areas under sanctions—either via tariffs or controls over trade and investment—have declined, while those not being sanctioned continue to grow. For example, according to Chad Brown of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, US imports of Chinese goods under increased tariffs fell by 25 percent from 2017 to 2022 while imports of non-taxed goods increased by 42 percent—pushing the bilateral trade volume to a new record high of $690 billion in 2022. Yet, while Yellen mentioned the record trade volume with China as proof that there has been no decoupling, she did not report that the United States recorded a trade deficit of $382 billion with China in that year, compared to a deficit of $375 billion in 2017, at the beginning of then President Donald Trump’s trade war with China. In this context, continued growth in trade volume and deficit with China may not be something to look forward to—without adopting effective measures to safeguard US manufacturing capability.

The deeper problem is that the rhetoric of “de-risking, not decoupling” has been rejected by the Chinese, who see no difference between the two concepts—believing that both are about constraining China’s growth, especially in high-tech sectors crucial for future economic and military development. In particular, China views US “de-risking” measures in certain high-tech sectors as offensive actions meant to delay China’s progress and strengthen US leadership positions in those important areas.

It is also important to keep in mind that China has for a long time attempted both de-risking against US sanctions (mainly by trading more with the Global South and developing alternative settlement mechanisms for cross-border economic transactions) and decoupling by promoting self-sufficiency in advanced tech and military developments.

Talk isn’t cheap, but…

Yellen concluded that her visit represents a step forward in maintaining frequent, high-level communications between the two countries, setting their relationship on “a surer footing,” but recognized that significant differences remain between the two. In fact, China hasn’t changed its positions, insisting that the United States has to take the next steps, dropping all sanctions. Given this reality, it is important for the United States to be clear-eyed about what it can expect from meetings with Chinese officials. While maintaining regular contact is better than having no contact, simply repeating to each other their respective well-known core interests is not going to solve any problems.

Meanwhile, the most important communication between the United States and China is not happening: that between the two militaries, which is critical to avoid an unwanted war in the western Pacific that could be triggered by accidents, mistakes, miscommunications, or misunderstandings. This lack of US-China military communication is particularly worrisome, and its resumption would be much more beneficial than statements about de-risking or decoupling during choreographed diplomatic visits.

Hung Tran is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center, a former executive managing director at the Institute of International Finance, and a former deputy director at the International Monetary Fund.

Further reading

Mon, Jun 19, 2023

Experts react: Blinken makes the rounds in Beijing. Will there be a US-China thaw?

New Atlanticist By

The US secretary of state has just wrapped up meetings with top Chinese officials in Beijing. Read insights from Atlantic Council experts on what was revealed and what to look for next.

Wed, Jun 21, 2023

How Beijing’s newest global initiatives seek to remake the world order

Issue Brief By Michael Schuman, Jonathan Fulton, Tuvia Gering

Recommendations on how US policymakers and European and Indo-Pacific partners can better understand China’s latest development and security initiatives to meet the rising competition.

Wed, Feb 22, 2023

The balloon drama was a drill. Here’s how the US and China can prepare for a real crisis.

New Atlanticist By John K. Culver

The communication breakdown between the United States and China could prove disastrous if a crisis arises that’s bigger than a balloon—which is why they need to start talking now.

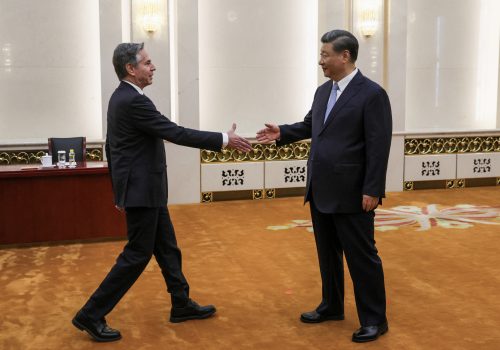

Image: Chinese Premier Li Qiang, right, shakes hands with U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, left, during a meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, Friday, July 7, 2023.