Iraqi President Barham Salih nominated a new prime minister candidate, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, on April 9, in the third attempt to appoint a new prime minister after Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi resigned in November 2019. The past two candidates were unable to form a government due to opposition from Iraq’s disparate political parties. Al-Kadhimi previously served as Iraq’s national intelligence chief.

If confirmed, al-Kadhimi will inherit a dizzying array of challenges from the spread of COVID-19, heightened US-Iran tensions that are playing out in Iraq, the economic blow to the government’s revenue from low oil prices, and popular demands for anti-corruption reforms and government accountability that unseated the previous government. Meanwhile, the United States on April 7 announced its intent for a new strategic dialogue with Iraq this summer to review the US economic and security role in that country.

Atlantic Council experts react to the nomination of Mustafa al-Kadhimi and the potential for a new US-Iraq strategic dialogue:

Abbas Kadhim, director of the Atlantic Council’s Future of Iraq Initiative:

“On the seventeenth anniversary of the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s tyrannical regime in Iraq at the hands of US forces, Iraqi President Barham Salih designated the chief of National Intelligence, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, to form the new Iraqi Council of Ministers and, if confirmed, to succeed caretaker Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi. The substantial support for al-Kadhimi among the leading Iraqi political blocs should make his task of forming a government and securing its confirmation in the Council of Representatives fairly easy if he submits a reasonably acceptable cabinet and a short-term program focusing on the immediate challenges that Iraq faces, namely the containment of the COVID-19 pandemic and the looming crisis of the sharp decline of oil prices, which could cripple Iraq’s oil-dependent economy.

“Al-Kadhimi was considered for the prime minister post after the 2018 general elections, and his name came up again after Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi resigned in November 2019, but he was rejected at that time by the widespread protest groups and several Iraqi militant groups. The protesters have dispersed due to COVID-19 and the unsuccessful prime minister candidacy of Adnan al-Zurfi, who spoke out strongly against non-state militant actors, has made al-Kadhimi’s candidacy more appealing. Furthermore, al-Kadhimi maintained no formal affiliation with any political bloc since his appointment to the top intelligence job.

“In addition to handling the economic challenge and COVID-19 pandemic, al-Kadhimi is expected pursue an aggressive reform agenda and prepare for a credible election. This will include the planning for the upcoming census, finalizing the election law, and reforming the High Election Commission. His government will also be expected to restore the lost balance between Iraq’s regional and international policy, particularly the challenge of being in the crossfire of an escalating US-Iran conflict.

“If confirmed by May 8, al-Kadhimi’s government needs to work immediately on selecting a delegation to conduct talks with the US government to shape future security and economic relations between the two countries as part of the strategic dialogue that was recently announced. However, these talks that are planned for June 2020 might be postponed if the COVID-19 crisis continues into the summer or if al-Kadhimi faces challenges in filling the relevant cabinet positions. In the past, governments were confirmed without naming ministers of interior and defense. The timetable does not allow the next Iraqi government much time to prepare for such important talks, especially given the more pressing domestic issues that will be on top of their agenda.

“Given the current conditions of Iraq and the global turmoil, al-Kadhimi is about to take up a very challenging role and will need all the help he can get, both domestically and internationally, to navigate the challenges facing his country.”

Kirsten Fontenrose, director of the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security’s Middle East Security Initiative:

“The nomination of al-Kadhimi has the potential to be a win-win. Like many of his Gulf counterpart intelligence service heads, he has a professional relationship with the intelligence communities in both the United States and Iran and is therefore a known commodity to both. As the United States, and hopefully Iran, can glean from the past two decades, there is no potential for a zero sum “us versus them” arrangement in Iraq, where either the United States or Iran is chosen as a partner and the other fully shunned. Al-Kadhimi’s first big job if approved will be to define what Iraq can pragmatically request from, and offer to, both.

“The potential spoiler here are militias who may not see the US-Iraq dialogue proposed for June 10-11 as in their interest. A group that uses the US presence to galvanize public opinion in their favor, to justify sustained funding from Iran, or that has their eye on contracts that US companies will compete for after negotiations could seek to undermine the promise of talks by conducting attacks on the US presence.

“Any person approved by parliament to serve as prime minister can only ensure de-escalation in Iraq between the United States and Iran if he can convince Iran to restrain its proxies. Tehran may be willing to do so if it sees in al-Kadhimi a shot at negotiating a further US drawdown.

“The faster al-Kadhimi is approved and a government can be formed, the more realistic talks in June become. Theoretically al-Kadhimi has thirty days to form his cabinet, although Adnan Al-Zurfi was not permitted this courtesy. If the United States and Iran both assess that he is the best option either of them realistically have, then it could buy us a month of clear skies in Iraq, free of rockets and jets.

“The onus is now on Iraqi political elites to put personal agendas on hold and expedite the formation of a good-enough-for-government-work Cabinet, since doing so may be the one thing that can prevent Iraq from becoming a war zone again.”

Thomas S. Warrick, nonresident senior fellow with the Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East Programs at the Atlantic Council:

“On April 9, Iraqi President Barham Salih nominated Iraqi intelligence chief and former civil society leader Mustafa al-Kadhimi to be the next prime minister of Iraq. This is one of those moments when history stands on a knife’s edge, capable of falling either way.

“Iraq needs a prime minister with a mandate from the parliament and the people, and al-Kadhimi represents the best chance in a long time for an Iraqi leader who understand the needs of the people for honest, competent, and responsive government. Al-Kadhimi is at once less connected to the political parties that Iraqi protesters rightly blame for corruption and inefficiency, and yet connected enough that all the major Shia parties showed up for the announcement of his nomination. Whether the parties will support him is not yet known. You can’t have reform unless you convince those in power to give you a chance—for Iraq, this is that moment. Like previous prime ministers, al-Kadhimi understands the importance of charting a course in Iraq’s interest, while staying on good terms with the United States, Iran, and Iraq’s neighbors. But most of all, he has the moral character and a reputation for speaking honestly that is the real reason he deserves confirmation by the Iraqi parliament.

“Al-Kadhimi has the reputation for being pro-American, but what he actually has is the patience, over the past twenty years, to educate US and, more recently, Iranian officials on the realities of modern Iraq. Some Iranian-backed militias may try to disrupt his candidacy with attacks on US military or diplomatic facilities, including the US embassy in Baghdad. If there was ever a moment for the United States to stay focused on the big picture, this is it: The United States needs to resist every effort to be drawn into any military retaliation that would prevent the Iraqi parliament from approving al-Kadhimi as prime minister.”

Barbara Slavin, director of the Atlantic Council’s Future of Iran Initiative:

“Since 2003, little has happened in Iraqi politics without Iran playing a role and the US assassination of Qasem Soleimani on January 3 did not alter that basic fact. Soleimani’s successor, Esmail Ghaani, arrived in Baghdad March 30 with a clear mandate to unite Iraqi Shi’ite parties around a prime minister other than Zurfi. Ghaani’s visit followed one by Ali Shamkhani, a former Iranian defense minister who now chairs Iran’s Supreme Council of National Security—the top security body in the Islamic Republic. While in Iraq, Shamkhani—who speaks fluent Arabic—met with his Iraqi counterpart and reiterated a call for US forces to leave the country.

“While al-Kadhimi hardly seems like an ideal choice from the Iranian point of view, he is a known quantity in Tehran. If Iran has signed off on him becoming prime minister—and convinced Iran-backed militias and parties to agree—it is because al-Kadhimi’s main task will be to negotiate the withdrawal of US military forces from the country. How this is accomplished, and whether it can take place without more bloodshed, will be a test of the diplomatic skills of the United States, Iran, and Iraq and will determine whether the United States can still play a role in helping Iraq become a successful, sovereign nation. During this delicate time, all sides need to refrain from more killing. If the Trump administration thinks it can withdraw with honor from Iraq while still using it as a battleground with Iran, it will be sadly mistaken.”

C. Anthony Pfaff, nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Iraq Initiative:

“Unsurprisingly, Adnan al Zurfi’s bid to become Iraq’s prime minister has come to an end. Given his reported close ties to the United States, his only hope of overcoming the veto power of the Iran-backed Fatah bloc was obtaining the combined backing of the Sunni and Kurdish parties as well as Sadr’s more nationalist “Alliance for Reforms” party. These parties, however, chose not to get involved after five Shia parties, including those not affiliated with Iran, expressed their opposition.

“In his place, President Barhim Salih has nominated Mustafa al-Kadhimi, who currently leads the Iraqi National Intelligence Service (INIS). Like Zurfi, he is reported to have good relations with the United States. Unlike Zurfi, his ability to maintain his position as head of Iraq’s premier intelligence organization suggests he may be able to balance the parties’ competing interests and achieve the nomination.

“Also unlike Zurfi, al-Kadhimi is rumored to be close to Muqtada al-Sadr, suggesting that even if Iran-backed parties oppose him, he will be able to garner enough votes to overcome that opposition. Also working in his favor is the fact that the Iraqi people, especially the Shia, have clearly demonstrated their sensitivity to even the appearance of Iranian influence. So, if they perceive any failure of his nomination to be the result of Tehran’s meddling, not only will protests likely renew, the Fatah bloc may suffer when elections finally do happen. These factors, along with everyone’s interest in ending the deadlock, likely constrain their options in opposing al-Kadhimi, especially if the other parties support him.

“So, while it is reasonable to hope that al-Kadhimi’s nomination might succeed, there is less reason to hope that he will be able to address conditions that prevent Iraq’s recovery and drive the protests. Iraq needs a prime minister who can combat corruption, improve government effectiveness, and direct resources towards infrastructure and service improvements. Given the fact that doing so will take resources away from Iraq’s kleptocrats, who are well-represented both in government and parliament, getting the necessary political capital to do so may be daunting, especially since al-Kadhimi does not have a party affiliation of his own. Exacerbating the situation is the fact that the spread of COVID-19 in Iraq will mean fewer resources will be available to meet what will be a growing need.

“Of course, the new prime minister’s immediate mandate is to get the country to the next elections, which is much more modest than recovery. In this regard al-Kadhimi may indeed be successful. Most importantly for the United States, however, he is in the best position of all the previous nominees to address militia attacks against US forces, which will allow the United States time to negotiate a mutually beneficial security relationship while not appearing to be giving in to pressure from Tehran. Achieving those two things alone would not only give hope to improving conditions in Iraq but also to improving its relations with the United States.”

David Mack, nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs:

“US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s remarks of April 7 are a refreshing sign that the US administration has come to a realistic understanding of what lies ahead for US-Iraq relations. In proposing a broad dialogue between Washington and Baghdad, he said, “All strategic issues between our two countries will be on the agenda, including the future presence of the United States forces in that country and how best to support an independent and sovereign Iraq.” He coupled this by designating Under Secretary David Hale, the highest-ranking career State Department diplomat, to head a delegation for talks in Baghdad with a new Iraqi government.

“The evolution in US policy in the wake of the military strike of January 3 on Baghdad Airport that eliminated Iran’s top general and Iran’s top Iraqi militia asset is striking. On January 10, the State Department reaction to reports that then Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abd al-Mahdi asked the United States to send a delegation to Baghdad to begin preparing for a pull out of US troops was an adept holding action. It concluded, “There does, however, need to be a conversation between the US and Iraqi governments not just regarding security, but about our financial, economic, and diplomatic partnership. We want to be a friend and partner to a sovereign, prosperous, and stable Iraq.” Notable by its absence was an explicit recognition that meaningful talks would need to include serious negotiations for the withdrawal of forces.

“Since then, there have been a series of punches and counter punches by Iranian influenced Iraqi militias and US military forces. One after another, Iraqi political leaders, including those who are well disposed to the United States, have indicated that they do not want their country to be a battleground between the United States and Iraq. It has taken three months to return to a policy that builds not on the presence of US military forces but on the broad interests that were recognized in the Strategic Framework Agreement negotiated between Baghdad and Washington over a decade ago.”

Further reading:

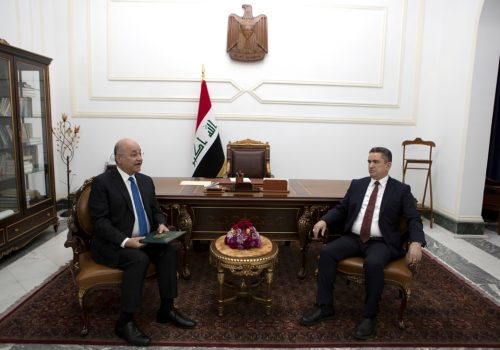

Image: Iraq's President Barham Salih instrcuts newly appointed Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi in Baghdad, Iraq April 9, 2020. The Presidency of the Republic of Iraq Office/Handout via REUTERS