The COVID-19 pandemic is inflicting economic damage across the world. And that damage may be having an insidious knock-on effect: eroding faith in democracy, especially among young people. Millennials across the globe are more disillusioned with democracy than any other generation was at the same stage of life, according to the Bennett Institute for Public Policy at the University of Cambridge, and their current level of faith in the system remains lower than that of every other age group. Around the world, youth satisfaction with democracy is on the decline; 55 percent of Millennials say they are dissatisfied with democracy, whereas less than half of Generation X reported such discontent at the same age.

According to the report, this disillusionment isn’t simply a matter of age. Instead, the differences among generations may also be a result of the events of the last decade—including the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis and steep increases in inequality. And according to the Pew Research Center, two of the main reasons people around the world are more likely to be dissatisfied with democracy have to do with economics. Those who don’t think favorably of their country’s economic conditions and don’t believe the average person has seen his or her financial situation improve in the past twenty years are more prone to such dissatisfaction. The economic system that worked for Generation X and Baby Boomers no longer works for Millennials, and frustrations over this reality are dimming views of democracy itself.

This loss of faith is not surprising considering the world young people are confronting these days. In the United States, for example, college students graduating in 2020 entered a labor market blighted by high unemployment and freighted with financial and professional consequences that could last ten to fifteen years after graduation. Last year, American colleges propelled nearly two million graduates with bachelor’s degrees into the worst recession since the Great Depression.

Some of these recent graduates in the United States, moreover, lacked access to unemployment benefits. Those who had jobs while in school or had a job lined up for after they graduated were allowed to collect benefits, but those without a concrete job offer and no previous employment record were excluded. Today, three in ten young adults in the country are neither working nor in school. Recent college graduates were already saddled with financial burdens from student debt, which has now reached a total of $1.7 trillion—exceeding car loans and even credit-card debt.

More broadly, America’s younger generations still bear the economic scars of the Global Financial Crisis more than a decade ago. Their lives have now been tainted by two major recessions that have limited economic opportunity and made it harder to stay on the economic trajectory that older generations have followed.

This specific suffering of young people in this crisis, and the threat the crisis poses not just to their welfare but the welfare of democracy, should be top of mind for members of Congress as they chart the road to economic recovery. Lawmakers should seriously explore a youth agenda that includes expanded unemployment benefits for recent graduates and students, the inclusion of dependents over the age of eighteen in stimulus checks, and policies aimed at creating more entry-level jobs—through infrastructure programs or investments in sustainable energy, for example—to prevent young generations from falling even further behind.

But to meet this moment, economic policies must also transcend it and offer long-term solutions. The last time the United States suffered two back-to-back major recessions was in the 1930s and 1940s, resulting in policies such as the GI Bill, which helped veterans continue their education tuition-free rather than flood the job market. This is another one of those moments that calls out for transformational reforms.

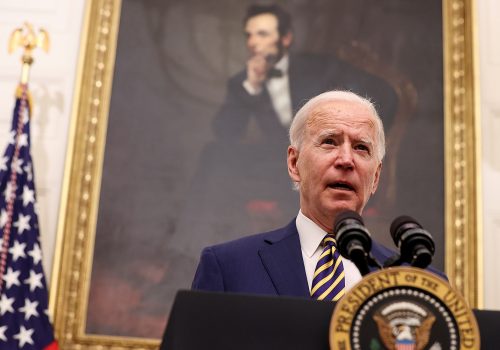

The first big step could be revisiting the cost of higher education. The student-debt crisis is only worsening, with college becoming ever more expensive even as it also becomes ever more essential. Students are forced to choose between accumulating crippling debt or limiting their future prospects. By answering President Biden’s call for guaranteeing tuition-free education at public colleges and universities for students with family incomes below $125,000, and for forgiving $10,000 of student debt for each graduate for every year they dedicate to national or community service, Congress can begin to cut down on the $1.7 trillion tab with which the country’s younger generations have been stuck. Washington failed to repair the deep economic fractures that the Global Financial Crisis left behind. If younger generations are to be prevented from growing further disillusioned with their economic conditions and democracy itself, the United States must not make the same mistake again.

Amanda Dickerson is a contributor to the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.

Further reading

Image: A woman and her son are seen in their 60-square-foot sub-divided flat. REUTERS/Tyrone Siu