Two weeks before the 75th anniversary of the Bretton Woods Agreements is celebrated, the World Trade Organization (WTO) issued a decision certain to intensify trade war rhetoric and escalate transatlantic trade tensions. The move does not surprise many trade policy experts, but it will further unsettle a global trading system undergoing already difficult rebalancing.

How did we get here?

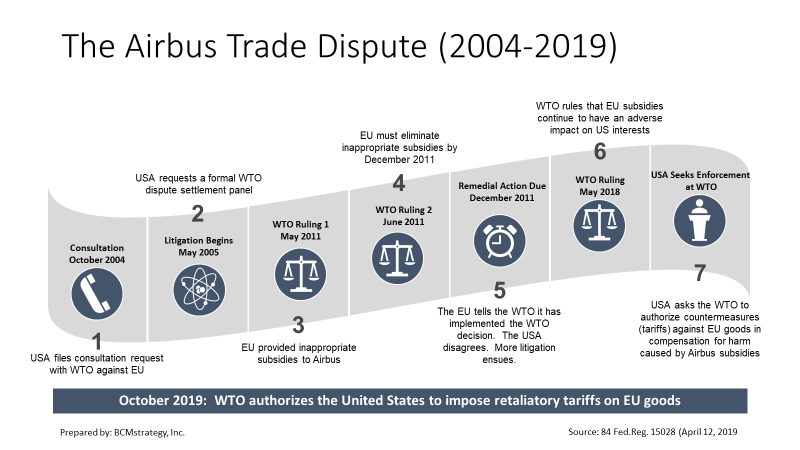

This should not be a “headline risk” situation, where an unexpected news story rattles markets. As the infographic below illustrates, this dispute has been simmering for over a decade. It has occupied the political leadership of three US presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald J. Trump) and soon three EU Commission presidents (José Manuel Barroso, Jean-Claude Juncker, and president-elect Ursula Von der Leyen).

A countersuit from the European Union (EU) regarding subsidies provided by the United States to Boeing is also crawling through the slow WTO judicial system, which means transatlantic trade tensions are certain to increase even if the only actions taken from here involve implementing WTO decisions.

The timeline spans the most consequential geoeconomic rebalancing since World War II. The core rulings in 2011 occurred amid the EuroArea bond market crisis during which five EU Member States were required to conclude bailout agreements. The 2011 WTO rulings came at a most inconvenient moment for Europe. Withdrawing support from Airbus at that time would only have exacerbated severe economic stresses at the core of the European and the Group of Seven (G7) economies (France and Germany).

The current rulings occur amid a political climate in which both the extreme right and the extreme left have amassed significant popular support for anti-trade and anti-globalization policies that reject many of the core features of the multilateral trading system. In Brussels, a newly installed EU leadership may additionally be tempted to take a hard line in order to show political resolve and resistance against an unpopular US government. They should resist the temptation.

What comes next?

At the procedural level, and as widely expected, the United States will now increase tariffs on a broad range of European imports. European officials have suggested a negotiated compromise as an alternative to a fresh round of tit-for-tat tariffs.

It is crucially important at this stage to distinguish between tariff increases authorized in advance by the WTO and unilateral or retaliatory tariffs imposed without consultation and approval from the WTO. Tariff increases under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 can be used to implement WTO decisions under US domestic law. Tariff increases under Section 232 are undertaken unilaterally for the purpose of addressing “national security” concerns and operate outside the WTO umbrella.

The “232 Tariffs” have dominated the news in the last eighteen months, as the Trump administration placed national security tariffs on steel and aluminum on Europe and other partners, and threatened to impose national security tariffs on foreign automobile and automobile parts imports including, but not limited to, European auto imports. The next inflection point will occur in November 2019, when the government’s self-imposed deadline for a decision on these auto tariffs comes due.

How US and European policy makers react to the WTO decision in the aircraft sector will likely determine how US policy makers proceed regarding the auto sector tariffs. Trade policy risks have thus increased overnight.

If EU policy makers overplay their hand, the Trump administration could believe itself to be justified in assessing Section 232 tariffs against EU vehicle imports. Considerable damage to the integrated fabric of the transatlantic economy would ensue, as this infographic from the Atlantic Council illustrated earlier this year.

The adverse impact on the US economy could be mitigated if Japan is exempted from the auto sector tariffs. This is nearly a doomsday scenario for Europe, but it is not implausible. Having just negotiated a bilateral trade agreement with Japan regarding agricultural and digital trade (an estimated US export value of $7 billion), and facing pressure to increase US economic presence in the Pacific, policy makers in Washington could be tempted to execute a Pacific pivot in trade, which Europe traditionally has viewed negatively.

The damage to the transatlantic relationship from this scenario cannot be overstated and goes far beyond the economic value of transatlantic trade. If Washington is goaded into—or chooses unilaterally—to impose auto sector tariffs on European auto imports one month after the WTO’s Airbus ruling, it will effectively be labeling its transatlantic allies as threats to US national security. A newly installed EU leadership will have every incentive to prove itself by reacting strategically or asymmetrically, if not swiftly.

The best possible outcome, of course, is that policy makers in Brussels and Washington find a negotiated solution that counterbalances the dramas in the goods sector (which is not actually the largest segment of transatlantic trade flows) with positive action in the services sector (which is the center of gravity for transatlantic trade). Quiet transatlantic progress this year in the soybeans sector and the G20 Osaka Summit outcomes could provide the foundation for more constructive engagement regarding digital trade. Having successfully and legally imposed $7 billion in tariffs, the Trump administration could take a victory lap and determine that auto sector tariffs are unnecessary.

Other factors may also create incentives for the Trump administration to pull back from the automobile tariff cliff. Another round of retaliatory tariffs between the United States and Europe could generate unwanted ripple effects that threaten to upend the already tepid Congressional support for ratifying the US-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement (USMCA) as noted in this recent article from The Hill.

Is this a Goldilocks scenario? Possibly.

It is very much an open question whether any government in the United States would be willing or able to avoid taking trade policy action that would potentially impact adversely its voter support in the automobile economies of Michigan, Tennessee, South Carolina, Alabama, and Indiana. Even with a truce in a strategically significant sector (digital trade), US policy makers would still have to explain to the domestic auto industry why it failed to raise tariffs on foreign (particularly European) vehicles. Successfully making this case would require the administration to convince the auto sector that they are data companies now, not transportation companies. It would be a hard sell.

If “232 Tariffs” are imposed on vehicles in November, at a minimum we can be certain that Japan or the EU or both would file suit against the United States at the WTO contesting 232 tariffs in the auto sector. The WTO ruling regarding Airbus therefore may be a “win” for the multilateral system and for the United States, but it creates a potentially irresistible temptation for both US and European leaders to take hard positions.

Two additional issues loom as a consequence of the ruling.

First, the extraordinary delays in adjudication at the WTO must be addressed. Many have written about the judicial crisis in the WTO. This case is a good example. It should not take nearly twenty years to address a subsidies dispute of this magnitude. Among other things, the delay permits inappropriate subsidies to become part of the fabric of society, making them that much harder to unravel later when the WTO adjudicates the dispute.

Second, the WTO case was filed against the entire European Union…which at the time included the United Kingdom. If a hard Brexit should occur at the end of this month, then policy makers and lawyers in London, Brussels, and Washington will have one more technical negotiation to conduct in order to apportion liability for the UK contribution to the illegal subsidies.

What does it mean?

Ironies and contradictions abound.

- A US administration that has railed publicly against multilateral institutions will now be enforcing a multilateral judicial decision.

- The European Union, which has long railed publicly in support of multilateral institutions, must now call for the judgement to be set aside in favor of a negotiated bilateral solution.

- A WTO ruling (which is supposed to safeguard level playing fields and free trade) is likely to trigger increased bilateral and unilateral tariffs in the transatlantic economy.

Aggressive action outside that WTO umbrella could weaken further a system already fragile from accelerating geoeconomic rebalancing in a Distributed Age which increasingly questions the value and necessity of centralized economic structures. The ripple effects would not be pretty.

The Bretton Woods structure did not expect sovereigns to be angels. Policy makers in New Hampshire in 1944 expected that domestic political pressures would generate irresistible pressures on national leaders to protect favored economic and political sectors through increased trade barriers. The structure provided for a process in which sovereigns could seek compensatory relief—legally under international law—without the risk of triggering a debilitating trade war.

Policy makers now have an opportunity to reaffirm their support for this multilateral framework during a milestone anniversary year by implementing this WTO ruling and any ruling in the parallel Boeing case. If policy makers can resist the urge to create a rhetorical firestorm, following the process for authorized tariff increases and consequent negotiations under the WTO umbrella could provide a framework for working through the geoeconomic rebalancing that is already underway informally.

Let’s hope for the best.

Barbara C. Matthews is non-resident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council. She is also Founder and CEO of BCMstrategy, Inc., a start-up company that uses patented technology to quantify public policy risks and anticipate outcomes. Matthews as served in senior positions within government on both sides of the Atlantic, first as Senior Counsel to the House Financial Services Committee and then as the first U.S. Treasury Attache to the European Union with the Senate-confirmed diplomatic rank of Minister-Counselor.

Further reading

Image: European Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom attends an interview with Reuters in Geneva, Switzerland June 14, 2019. REUTERS/Denis Balibouse