World War II in Europe ended seventy-five years ago today and, as Winston Churchill wrote, it brought triumph and tragedy. The Allies had beaten Nazi Germany and liberated Western Europe. The United States, its homeland almost untouched by war and power at a peak, set to order a post-war world designed to prevent a repeat. Unlike the US failure at world order after World War I, it worked.

Pax Americana was a new kind of hegemony: a liberal, rules-based order that favored freedom and provided an umbrella for general prosperity. The United Nations didn’t work out as Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman wanted, but new global financial institutions (the International Monetary Fund and World Bank), the Marshall Plan, NATO, and more did. Europe stopped its endless wars and, with US support, knit itself together in what became the European Union. We called it the free world. A miracle.

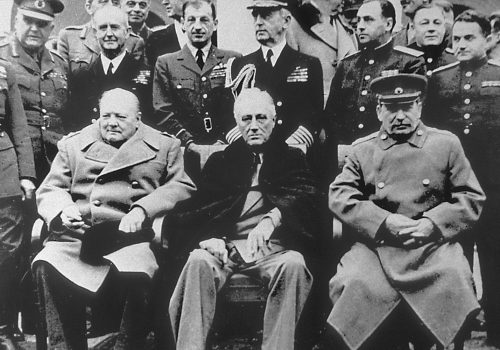

Not for all, however. US withdrawal from international responsibility in the 1930s—the argument of the original America First movement—meant that to defeat Adolf Hitler, the United States and the UK had to ally with Josef Stalin, a tyrant in Hitler’s league. Thus, a tragedy: liberation applied only to Western Europe while one-third of the continent, including Poland, which had fought the Nazis from the first day of the war to the last, on all fronts, spent forty-five more years under tyranny.

But Communism could not stay the course; it weakened internally and, in 1989, Central Europeans and Balts overthrew it, acting for their nations and, simultaneously, in the name of the free world. That worked, too. After 1989, the West extended its liberal order to all of Europe, and Central Europe had its own miracle of growth.

There were blunders, failures, and hypocrisies along the way, and the recent record is heavy with them. The US war in Iraq, the great recession and EU financial crisis, rising income inequality in the United States and stagnation in Europe, social stresses and unequal gains in Central Europe, all fed a sense that perhaps the post-1945 order and even its principles were done.

US President Donald J. Trump campaigned making such arguments and has maintained them (though his administration has not acted on his more extreme rhetoric). Trump’s unsteady response to the coronavirus has intensified concerns on both sides of the Atlantic (and some glee from our adversaries) that the US-led rules-based order and US leadership itself is at an end.

But don’t write off the United States or the liberal order just yet. It’s a trope to look back at achievements of the past seventy-five as a golden age from which have fallen. It wasn’t. Americans thought we were losing the Cold War almost from the start. The late 1940s, the now-lauded “Present at the Creation” era, included communist victory in China and the USSR making the atomic bomb; in 1950 the Korean War started. It all seemed a mess. Former secretaries of state Dean Acheson and George Marshall, now lionized, were reviled with a partisan heat to match current standards.

There were other predictions of disaster as well. In the 1970s, the US-led system was seen as failing at home and abroad, as demonstrated by social upheaval, assassinations, regular urban riots, defeat in the Vietnam War, political rot revealed by Watergate, economic failure (stagflation), and slippage in the Middle East (the oil embargo and gas shortages, and the fall of the Shah). Then, as now, respectable op-eds started presuming that the world order since 1945 was failing, along with American leadership.

These were real problems. Dark assumptions then and now didn’t come from nothing.

Yet we always outran predictions of disaster. For seventy-five years, the United States and its allies found ways to adapt and shift, while maintaining true to core principles. They remade the global monetary system, helped whole new industries arise, helped 100 million self-liberated Europeans get on their feet, found (with at least initial success) ways to accommodate new and rising powers around the world, while, at home, opened up their countries in ways unimaginable to prior generation.

The challenges now are hard, but no harder than what the free world has already achieved. Despite partisan rancor at home and European skepticism about Trump, elements of a consensus agenda exist, waiting to be assembled: solidarity in combating the coronavirus (sharing, not stealing or hording, equipment, medicine, and a vaccine); coordinated efforts at avoiding a global depression through near-term spending and addressing supply chain issues without protectionist trade wars; pressing China to play within agreed rules; resisting Kremlin aggression while investing in a potential better future with Russia. Judging by his Foreign Affairs article, a Biden administration would embrace this and more—though it could choose not to—and so could the Trump administration.

From V-E Day seventy-five years ago, the United States put a new kind of grand strategy into practice: we understood that, ultimately, our interests advanced with our democratic values, and that our prosperity depended on the prosperity of other nations. We fashioned a global system on that basis. For all its shortcomings, it’s better than the competition. The trick now is to use those core principles to meet the next seventy-five years.

Daniel Fried is the Weiser Family distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was the coordinator for sanctions policy during the Obama administration, assistant secretary of State for Europe and Eurasia during the Bush administration, and senior director at the National Security Council for the Clinton and Bush administrations. He also served as ambassador to Poland during the Clinton administration. Follow him on Twitter @AmbDanFried.

Further reading:

Image: An American soldier hugs an English woman and as crowds celebrate Germany's unconditional surrender at Piccadilly Circus, in London, on May 7, 1945, in this handout photo provided by the United States National Archives. REUTERS/United States National Archives/Pfc. Melvin Weiss/Handout