Just months ago, the Indian government was boasting about its handling of the pandemic. Health officials prematurely declared victory over COVID-19 and began lifting restrictions, which, coupled with a botched vaccination campaign, has proven a recipe for disaster. Now a vicious second wave is sweeping the country and debilitating an already limited healthcare system. This public-health tragedy is a global concern—not just because of the spread of India’s triple-mutant variant, but also because of the ramifications for economic recovery worldwide.

In April, just before the world began to understand the extent of India’s second wave, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) increased its forecast for India’s economic growth in fiscal year 2022 from 11.5 percent to 12.5 percent. Those numbers are now set to be revised, but even then the forecast seemed unrealistic. While India suffered a massive economic shock in 2020, leaving plenty of room for bounce-back growth, structural challenges predating the pandemic make that level of growth almost unattainable. India’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth has been declining since 2016, and foreign investment in the country has similarly been declining since 2018. Years of poor financial management had stretched the government’s accounts. Tax collections had dwindled and the already huge deficit had continued to swell. The pandemic, and the fiscal strain that came with it, further exacerbated these conditions. For example, India’s vast informal sector, which accounts for half of its $2.9 trillion economy, is now decimated after various state and local lockdowns. And the second wave of COVID-19 is cutting incomes and burning through savings, raising the risk of yet another economic blow for Asia’s third-largest economy as it continues its struggle to recover.

The IMF’s World Economic Outlook forecast that emerging markets, including India, would grow 6.7 percent and that the global economy would grow 6 percent in 2021. The Indian economy makes up 11.8 percent of the collective GDP, based on purchasing power parity, of emerging markets and developing economies. Further evaluation of the IMF’s data reveals that more than a fifth of growth in emerging markets is expected to come from India. So how will the country’s newest COVID-19 wave impact the global economy?

Emerging markets are slated to contribute 64 percent of global economic growth this year. India’s 2020 GDP was just over $2.7 trillion. If India were to grow at only 5 percent this year, instead of the 12.5 percent the IMF predicted, it would cost the world over $200 billion in potential growth, an amount equivalent to Greece’s GDP.

Glum as this scenario is, it is arguably still too optimistic; India’s declining growth could have secondary effects that further impact the global economy. For instance, the United States and China, India’s largest trading partners, will inevitably see disruptions in their supply chains as a result of India’s economic slowdown. And India’s second wave and triple-mutant variant are now spilling over into neighboring countries. Nepal is currently undergoing a similar COVID-19 crisis and reporting more deaths per capita than India is. Thailand’s tourism sector and Vietnam’s manufacturing industry are shuttering following a rising tide of cases. The potential impact of the variant from India spreading to countries like Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States is unfathomable.

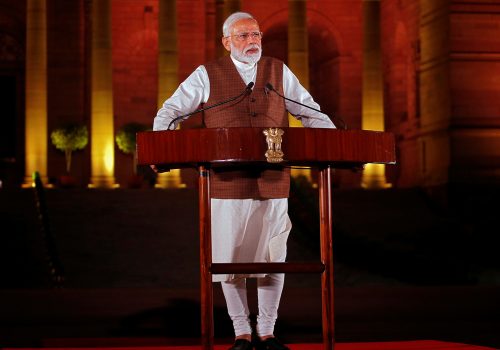

The world has responded to Indians’ cries for help. Countries from the United States to Saudi Arabia have been sending oxygen tanks, personal protective equipment, and other desperately needed supplies. Celebrities and Indians living abroad have mobilized and poured financial support into nongovernmental organizations helping alleviate the impact of this wave on India’s most vulnerable populations. Yet much of this support has been of little or no avail. The Modi administration has let medical supplies pile up at airports and has erected hurdles for credible civil-society organizations to receive foreign funding, all while directing money towards officially endorsed groups. Yogi Adityanath, the chief minister of India’s most populous state, has insisted that the state’s hospitals are not struggling from oxygen shortages, going so far as to order a crackdown on people who continue to highlight shortages.

But humanitarian disaster assistance is not enough: The international community must pressure the Modi administration to do all it can to bring India out of this crisis. American lawmakers have urged President Joe Biden to view the dire situation in India as a matter of national security, but international policymakers should also understand it as a matter of economic security that demands space at the top of the agenda at the upcoming Group of Seven (G7) summit in June. Anything less will make meaningful global economic recovery in 2021 impossible.

Nitya Biyani is a program assistant at the GeoEconomics Center.

Further reading

Image: A health worker dressed in a personal protection suit carries a stretcher after transporting the body of a person who died due to COVID-19 at Mangolpuri crematorium ground in New Delhi. Photo by Naveen Sharma / SOPA Images/Sipa USA via Reuters.