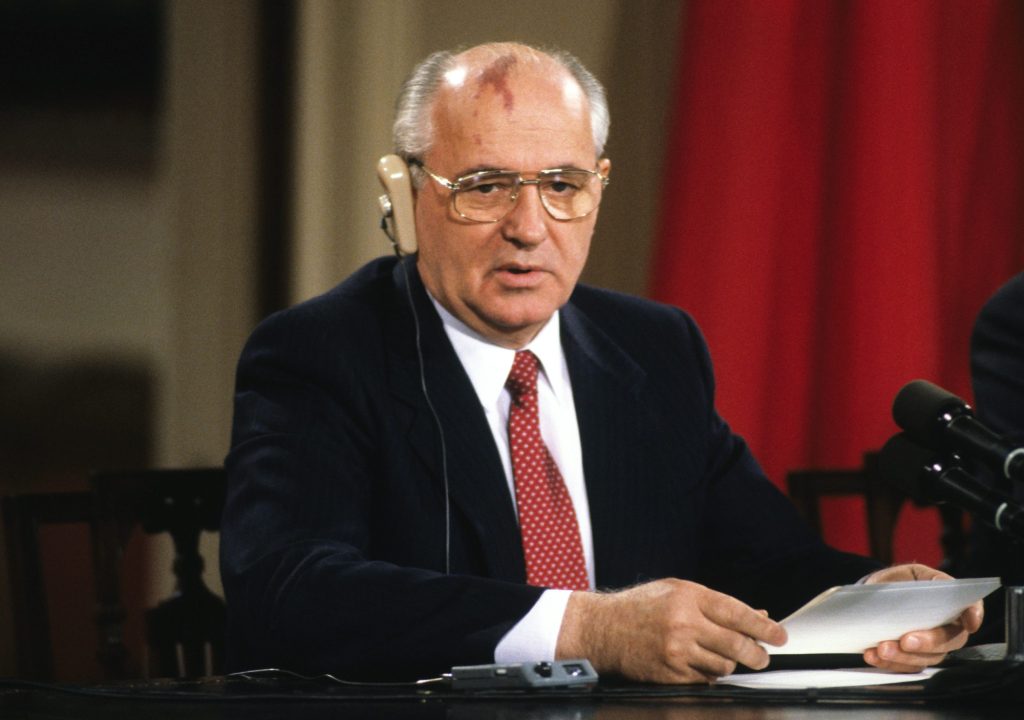

Few would argue that former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who passed away this week aged 91, was a figure of huge historical significance. However, reactions to his death varied greatly across Europe, reflecting a memory divide that is also evident in contemporary European attitudes toward Vladimir Putin’s imperial agenda. While Western European commentators celebrated Gorbachev for his role in ending the Cold War, those who grew up behind the Iron Curtain were far more inclined to view him as a Kremlin tyrant wholly undeserving of praise for the collapse of a totalitarian empire he fought to preserve.

Many of the most generous tributes to Gorbachev came from European leaders. EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen set the tone by tweeting, “Mikhail Gorbachev was a trusted and respected leader. He played a crucial role to end the Cold War and bring down the Iron Curtain. It opened the way for a free Europe. This legacy is one we will not forget.”

Such sentiments were widely echoed in Brussels and other Western European capitals, where Gorbachev has always enjoyed a remarkably benign reputation. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg lauded the former Kremlin ruler for “historic reforms that led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, helped end the Cold War, and opened the possibility of a partnership between Russia and NATO. His vision of a better world remains an example.”

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Reactions in Russia itself ranged from muted to hostile. While Russian President Vladimir Putin offered his condolences and acknowledged Gorbachev as “a politician and statesman who had a huge impact on the course of world history,” he also delivered a very public snub by confirming that he would not be attending the former Soviet leader’s funeral.

Others were more direct in their condemnation. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov took a swipe at the alleged naivety of Gorbachev’s efforts to reduce tensions with the Western world. “This romanticism did not materialize,” he noted. “There was no romantic period or honeymoon. The bloodthirstiness of our opponents has shown itself.”

The chilliness of this Russian response was entirely predictable. While Western audiences associate Gorbachev with the end of the Cold War, Russians blame him for the humiliations of the Soviet collapse and the bitter hardships of the 1990s. Since coming to power at the turn of the millennium, Putin has made it his mission to reverse the mistakes of the perestroika era and Gorbachev himself has become a symbol of national weakness.

Eurasia Center events

Some of the most powerful responses to Gorbachev’s death came from the countries of the former Eastern Bloc, with many declaring that they did not share the positive sentiments expressed in Western obituaries. There was tangible anger on social media as people voiced their dismay at sanitized portrayals of Gorbachev that whitewashed his role in bloody Soviet attempts to suppress independence movements throughout the USSR in the late 1980s. “Lithuanians will not glorify Gorbachev,” posted Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis. “We will never forget the simple fact that his army murdered civilians to prolong his regime’s occupation of our country. His soldiers fired on our unarmed protesters and crushed them under his tanks. That is how we will remember him.”

Some commentators from Central and Eastern Europe branded the overly enthusiastic appraisals of Gorbachev coming out of Western Europe as an example of “Westplaining,” meaning the tendency to lecture locals on regional issues in a condescending, overconfident, and often inaccurate manner. Former Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves spoke for many when he tweeted, “The hagiographic panegyrics to Gorbachev in Western Europe today are the perfect accompaniment to their position on visas: You people in the East of the EU don’t matter, your worries don’t matter, your issues don’t matter.”

The mood was similarly strident in Ukraine. While most government officials kept their counsel, many Ukrainians noted Gorbachev’s failed efforts to save the Soviet Empire and his personal responsibility for ordering hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians to take part in traditional May Day parades in the immediate aftermath of the 1986 Chornobyl nuclear disaster. They also pointed out that Gorbachev had repeatedly voiced his support for Russia’s 2014 invasion of Crimea and questioned why so many in the West continue to view him as a man of peace.

For many in Central and Eastern Europe, this week’s veneration of Gorbachev was one more example of Western Europeans failing to understand the true nature of Russian imperialism. While Gorbachev may appear comparatively benevolent when viewed alongside Josef Stalin or Vladimir Putin, he was nevertheless a totalitarian ruler with blood on his hands who owes his place in world history largely to the simple fact that he failed. As Anne Applebaum noted in a brilliant essay reflecting on Gorbachev’s legacy, “He presided over the end of a cruel and bloody empire, but without intending to do so. Almost nobody in history has ever had such a profound impact on his era, while at the same time understanding so little about it.”

Peter Dickinson is Editor of the Atlantic Council’s UkraineAlert Service.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

Image: Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev makes remarks during a joint press conference with United States President George H.W. Bush, at the conclusion of their summit in the East Room of the White House in Washington, DC on Sunday, June 3, 1990. Photo by Ron Sachs / CNP /ABACAPRESS.COM