The sociologist Daniel Bell liked to remark, “My Kronstadt was Kronstadt.” Mine came in sixth-grade when I read—no, devoured—Alexander Dolgun’s memoir An American in the Gulag, a harrowing account of his interrogation by Joseph Stalin’s secret police and imprisonment in the Gulag. It left an indelible impression on me. From that moment on, I never wavered, never deviated, never flinched in my abhorrence for communism. A crusader in short-pants, I was more than happy to remind anyone within earshot about the perfidies of Bolshevism. When I entered Oberlin College in 1983, I was a professional anti-communist in all but name, left incredulous by the revisionist defenses of Lenin and Stalin that were percolating among the students and professors. By the end of the decade, I could take comfort in knowing that I had it right all along: the Warsaw Pact was going blooey. East Germany, where I had spent several weeks in the spring of 1987, was in turmoil. So was Poland. And Hungary, the pioneer of “goulash communism,” had opened its border with Austria. So much for the delusional notion on the western left that some purer form of Marxism could be rescued and redeemed from the rotten mess that Lenin and Stalin had left behind.

Even as anti-communism went belly-up along with the Warsaw Pact, however, a curious nostalgia accompanied a widespread sense of triumphalism about the end of the Cold War. The certitudes of the Cold War, after all, had provided a comforting, even reassuring, intellectual framework. In retrospect, Georgi Arbatov was on to something when he proclaimed in the late 1980s, “We are going to do a terrible thing to you. We are going to deprive you of an enemy.”

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

The enemy may have peacefully disappeared almost overnight, but memories of the East-West standoff continue to shape our perceptions of the present. In some ways, this may not be a bad thing. The US-Soviet rivalry was about more than a balance of power. It was about morality. And it was about the ability of ordinary people trapped behind the Iron Curtain to live their lives as they saw fit. This was especially so for Soviet Jews, who, from the 1970s onwards, sought an exodus from oppression but never entirely shed the mental luggage that they carried with them.

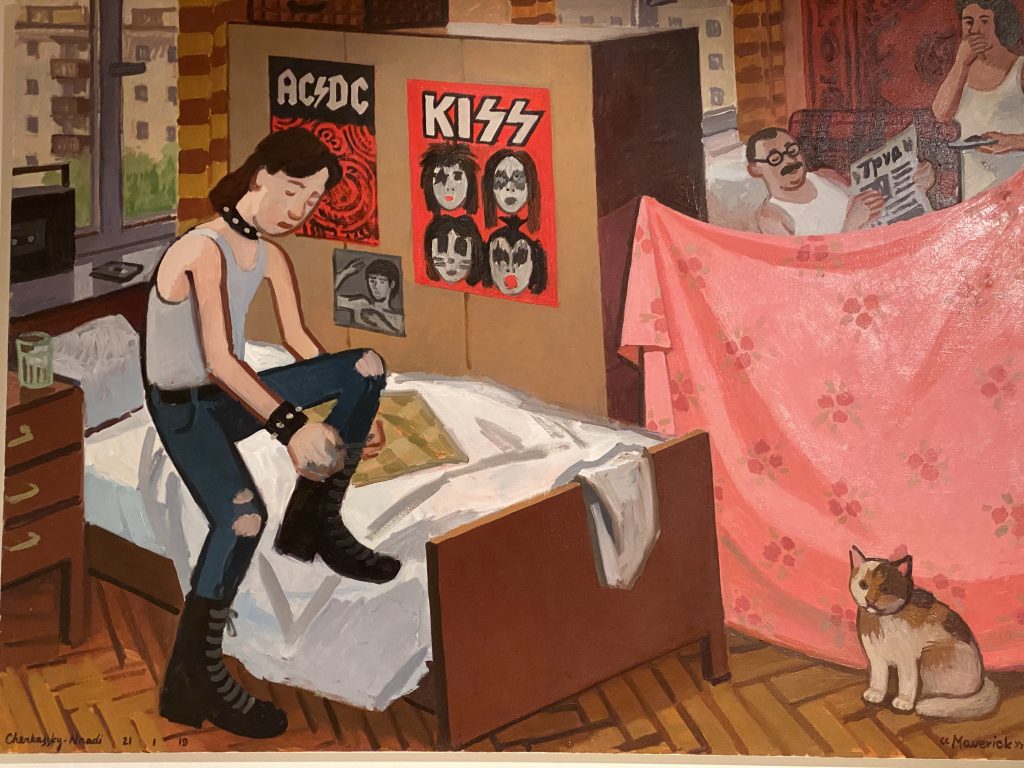

These musings are prompted by the work of the Ukrainian-born, Israel-based artist Zoya Cherkassky whose recent paintings vividly evoke the late Soviet era. She has observed, “It’s childhood so even if it’s something unpleasant you remember it with some sort of nostalgia.” Born in Kyiv in 1976, she emigrated with her family in 1991 to Israel a few months before the Soviet Union imploded. Her paintings are bold, lusty, and provocative. Last summer, she held an exhibition at Fort Gansevoort in New York of paintings that the New York Times dubbed “painted valentines to the Soviet era.” I was smitten and bought several of them, including “Maverick” which depicts a Ukrainian family in a tiny apartment partitioned by a bed sheet. It features dad complacently reading the newspaper and mom aghast at the getup of her son, a punk rocker lacing his boots next to a cabinet festooned with Kiss and AC/DC posters. Another intensely engrossing painting was called, “The Voice of America.” It shows Cherkassky’s father—her family members often appear in her paintings—listening intently at the kitchen table to Voice of America (one can’t help wondering what he would make of the current ructions at the agency).

The enemy may have peacefully disappeared almost overnight, but memories of the East-West standoff continue to shape our perceptions of the present.”

“Nunchaku,” another painting by Cherkassky, offers a reminder of the intimate nature of communal living in the East bloc. Photo credit: Jacob Heilbrunn

Another painting that I fell for was “Nunchaku.” It, too, offers a reminder of the intimate nature of communal living in the East bloc. It’s so carefully drawn that one can almost feel the tawdry, iridescent green wallpaper that lines the hallway where a beefy grandson in trackpants is perfecting his martial dexterity before a mirror as grandma, apparently unafraid of being whacked by a stray nunchuck, patiently waits behind him with a pot of porridge. Cherkassky’s paintings help to refocus our attention from the western to the eastern side of the Cold War, where listening to a VOA broadcast was verboten.

Cherkassky has hardly confined her efforts to recalling her Soviet childhood in Ukraine. For example, Cherkassky, whose husband emigrated to Israel from Nigeria, has focused on racism in Israel in a number of her paintings. More recently, during quarantine, she has focused on depicting Jewish life in Europe before World War II as well as a portrait of Stalin smiting the Nazis and the Angel of Death (a skeletal Wehrmacht soldier) slaughtering Soviet civilians.

Haaretz has praised her as “the eternal dissident,” noting that she has “many enemies, who think she is bringing art down to the level of a social manifest that has nothing to do with art, and some who vigorously argue against the political meaning of the paintings.” But there is more to it than just dissidence. She stands, above all, for something permanent and enduring, drawing on the deep traditions that she encountered both in Ukraine and in Judaism. Perhaps it’s not a stretch to view her as an archivist, mediating episodes from the past. As her powerful images suggest, she’s no shrinking violet but a clarion voice whose images achieve a poignancy that all but the most refractory viewers will find mesmerizing.

Jacob Heilbrunn is editor of the National Interest, a columnist for Spectator USA, and a senior writer for The Absolute Sound. He tweets @JacobHeilbrunn.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

Image: “Maverick” by the Ukrainian-born artist Zoya Cherkassky depicts a Ukrainian family in a tiny apartment partitioned by a bed sheet. Photo credit: Jacob Heilbrunn