Russia continues to ignore international concerns about attacks on press freedoms, including those expressed by US President Joe Biden at his June 16 summit with Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin. In a post-summit press conference, Biden said he had “raised the ability of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) to operate, and the importance of a free press and freedom of speech.”

Russia’s crackdown on RFE/RL continues despite Biden’s comments. One of the most recent targets is Vladislav Yesypenko, a RFE/RL contributor who was arrested in Russian-occupied Crimea on March 10. Yesypenko faces trial on July 6 on charges of spying and possessing a grenade.

He has been incarcerated for over three months. In April, the journalist’s lawyer claimed Yesypenko had been tortured with electric shocks and forced to confess that he was gathering intelligence for the Ukrainian authorities. His lawyer added that the grenade discovered by police had been planted in Yesypenko’s car.

Western governments and human rights organizations have condemned this prosecution, along with many other similar acts, without success. Yesypenko is a Ukrainian citizen who lived in Crimea prior to the Russian occupation, when he left the peninsula. He was apprehended while on assignment in Crimea freelancing for RFE/RL to cover a cultural event. If convicted, he faces 12 years in prison.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty is currently experiencing a sustained assault from the Russian authorities. “This is the culmination of years of efforts by the Kremlin to limit our access to the Russian audience. They now apparently view us and other independent media outlets as so threatening that we should not even be allowed to maintain a physical presence in Moscow,” RFE/RL’s President Jamie Fly told The Daily Beast.

RFE/RL has consistently provided coverage of issues regarded as sensitive by Kremlin censors such as the recent nationwide protests in support of imprisoned Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny. The US-funded outlet has also been a prominent source of independent information relating to Kremlin corruption, human rights abuses, and ongoing Russian aggression against Ukraine.

Yesypenko’s case has drawn fire from the government of Ukraine. On June 3, US officials raised the issue in a tweet calling for Yesypenko’s release. “The US is deeply concerned about Crimean journalist Vladislav Yesypenko. He remains in Russia’s custody where he was deprived for 27 days of the ability to meet with a lawyer. The United States calls for his immediate release.”

After Russia’s seizure and occupation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula in spring 2014, the Kremlin closed Crimea’s local media sites, newspapers, and radio, replacing them with regime-friendly outlets. In 2017, RFE/RL journalist Mykola Semena was charged with “separatism” and found guilty by a Russian court for an opinion piece denouncing the occupation. He was banned from journalism and public activities.

More arrests and convictions have followed. In 2020 alone, according to a report by the Justice for Journalists NGO, there were 58 attacks or threats on journalists in Crimea. Many of these attacks have focused on the Crimean Tatar community, which has suffered disproportionately during the Kremlin crackdown on freedom of expression and political dissent since the Russian occupation began seven years ago.

Besides jail sentences, other types of punishment have also been meted out. In November 2018, Ukrainian journalist Alena Savchuk and photographer Alina Smutko were banned from entering Crimea or Russia until 2028. Another correspondent, Tara Ibragimov, cannot enter the occupied peninsula for 34 years.

Eurasia Center events

In January 2020, Human Rights Watch accused Russia of specifically targeting Crimea in order to silence opposition to the occupation. “Critical reporting from Crimea is a major irritant to the Russian authorities,” commented Tanya Lokshina, associate Europe and Central Asia director at the New York-based human rights watchdog. “Barring independent journalists from the peninsula helps to choke the flow of information about their crackdown on Crimean Tatar activists and other abuses.”

The arrest of Yesypenko in Crimea comes at a time when Kremlin pressure on RFE/RL is mounting. Russia has designated RFE/RL a “foreign agent” along with its contributors, even though it operates as an arms-length journalistic organization. RFE/RL broadcasts in 26 languages across 22 countries and is funded by US Congress.

President Putin appears to consider RFE/RL an American version of Kremlin media outlets RT or Sputnik and is intent on forcing it out of Russia. To this end, Russians officials have frozen RFE/RL’s Russian bank accounts, ordered RFE/RL to designate its content and contributors as “foreign agents”, and imposed large fines for the outlet’s failure to do so.

According to current estimates, RFE/RL’s fines will total USD 33 million by the end of 2021. If these fines remain unpaid, the organization will be placed into bankruptcy and its media sites blocked, with RFE/RL officials facing the possibility of jail time.

The current Kremlin campaign against RFE/RL is part of a broader deterioration in the geopolitical climate that began with Russia’s February 2014 invasion of Crimea. Once again, Putin is demonstrating his disdain for the post-1991 international settlement and his willingness to challenge the verdict of the Cold War. The Kremlin strongman silences journalists and pro-democracy activists across Russia and in the Russian-occupied regions of neighboring countries, while at the same time waging a global information war of his own.

Diane Francis is a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center. She is Editor at Large with the National Post in Canada, a Distinguished Professor at Ryerson University’s Ted Rogers School of Management, and author of ten books.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values, and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia, and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

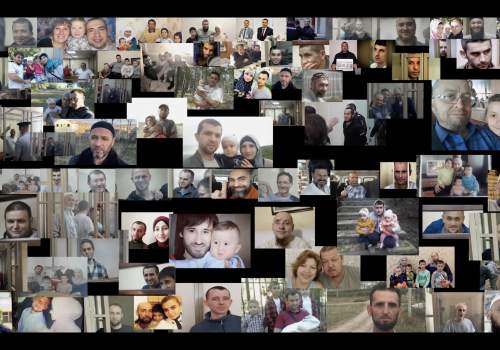

Image: RFE/RL freelance journalist Vladislav Yesypenko pictured in Crimea following his arrest on charges of spying for Ukraine. (Russian Federal Security Service/TASS via REUTERS)