One of the ways the experts at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center passed the second full year of the pandemic was by reading everything from politics, philosophy, and history to biography and, of course, fiction. Here are their favorite and often surprising top picks.

Brexit as history

It might surprise you to know that last year I read more and thought more about Brexit than at any point since the referendum itself. Tearing through a small library of memoirs and pamphlets, I found the two best Brexit polemics: Britain Alone: The Path From Suez to Brexit by the veteran pro-European journalist Philip Stephens and This Sovereign Isle: Britain in and out of Europe by the eminent Brexiteer historian Robert Tombs. Both are pertinent and flawed in mirroring ways, and when reading them back-to-back, it is like examining a freshly frozen core sample of this painful debate. Many might be appalled at the thought of plunging back into Brexit, but I disagree. The world is only just beginning to be able to analyze Brexit—at least the start of it—as history and not politics. I found it intriguing that each book mounts essentially the same accusation against the other side—that either Remainers or Leavers were looking for nostalgic imperial glory in joining or leaving the bloc—and this left me wondering whether a lasting and restrained post-Brexit consensus in foreign affairs might in fact eventually be found.

— Ben Judah, senior fellow at the Europe Center

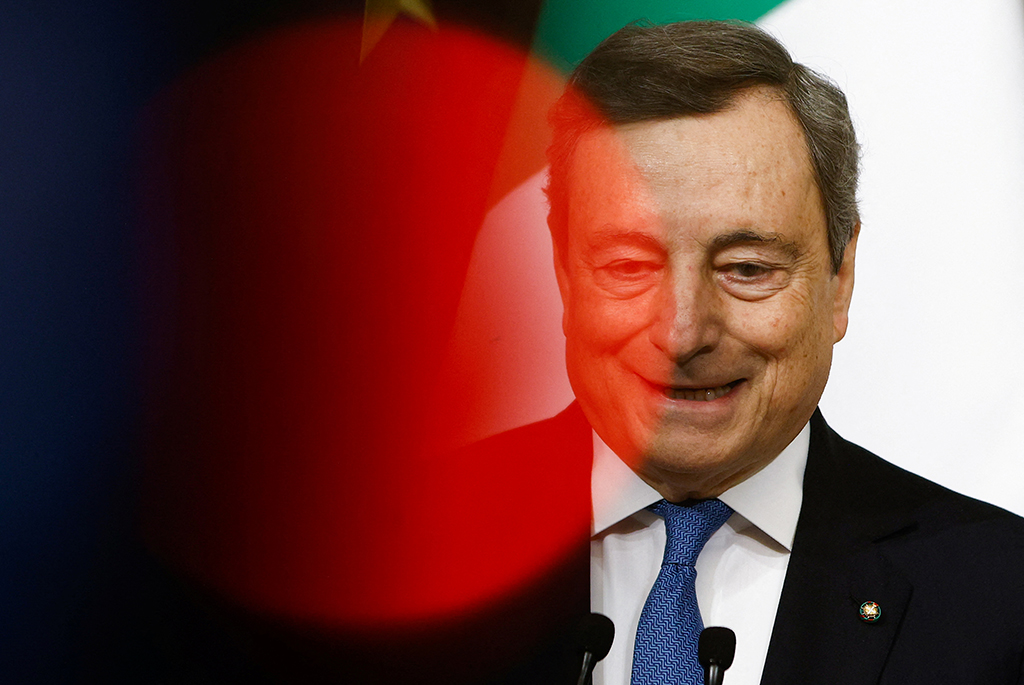

Draghi as Europe

A priority of mine since the pandemic began has been trying to work out how power is actually exercised inside the European Union (EU). What are the tactics and mechanics that see people move billions in bailouts and budgets? As a result, I spent much of the spring thinking about Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, the EU’s consummate practitioner, from having “saved the Euro” as head of the European Central Bank to being called back to “save Italy” as the country’s prime minister. I found L’enigma Draghi by journalist Marco Cecchini and Mario Draghi, l’artefice: La vera storia dell’uomo che ha salvato l’euro by Bloomberg’s Jana Randow and Alessandro Speciale, the two most indispensable chronicles of Draghi’s ultimate European career. Covering from Draghi’s time at the European Council to the Eurotower, the authors minutely catalog the bureaucratic and political power plays Draghi mastered in Brussels, Frankfurt, and Rome. Anybody trying to do analysis is indebted to journalists like Cecchini, Randow, and Speciale who follow their subjects up close for years and years to write the first drafts of history.

— Ben Judah

Paris-Brussels panorama

Like everyone else at the Europe Center, this was the year I tried to rebuild my big picture of European and global affairs after the first waves of the pandemic. Two books were crucial in rebuilding that for me: La France dans le bouleversement du monde by Michel Duclos, the eminent French foreign-policy thinker and former ambassador to Syria, and Pandemonium: Saving Europe by Luuk van Middelaar, the leading Brussels-based thinker and former EU official. The panoramic survey from Duclos offers unparalleled insight into how official France and Macron see and struggle with this emerging world, while Middelaar explains how official Europe was able to summon the power out of institutional improvisation to withstand the shock. Together they paint a picture of a sturdier Europe but one ever more alone in the world. These books should be required reading for Britons and Americans now dealing with the EU.

— Ben Judah

The United States and Russia

The crisis on Ukraine’s border serves as a bitter reminder of how much of a hash we have made of NATO enlargement since the end of the Cold War. M. E. Sarotte’s new book, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate, is a masterful account of the decisions that led to former US President Bill Clinton vastly expanding the alliance in the 1990s, and the fateful consequences of those decisions for relations with a fitfully democratizing, fragile Russia.

But more poignant than any of the alternative histories that spring to mind as one reads Sarotte’s engaging narrative is the haunting feeling that Western policymakers have learned little from their experiences. By that, I don’t mean to imply that all enlargement was obviously a mistake; the story told by Sarotte is too rich for such glib conclusions. The lesson, paradoxically, is one taught by the most hawkish NATO expansionists: Critics of the Partnership for Peace program in the 1990s, Sarotte says, “framed withholding Article 5 as giving Moscow a veto” on enlargement. This was undoubtedly a correct analysis and has been proven over and over again ever since the disastrous Bucharest summit in 2008. There, the compromise hatched over staunch European opposition to admitting Ukraine and Georgia was to insist on the validity of the aspirations of the candidates—even though politically their candidacy was dead in the water. Russian President Vladimir Putin seized on the opportunity not merely to “veto” the countries’ aspirations but to humiliate NATO itself, which clearly couldn’t bear to definitively shut the door. In Ukraine today, Putin continues to grind our noses in our impotence.

— Damir Marusic, senior fellow at the Europe Center

American hegemony

Another important book broadly relevant to transatlanticists that came out this year is Stephen Wertheim’s lively revisionist tome, Tomorrow, the World. Billed as an intellectual history of the United States’ drive to military primacy, the book adroitly traces how a community of Ivy League-educated thought leaders, shaken by the fall of France in 1940, concluded that the United States had no choice but to become a global hegemon. The details of how this doctrine developed are fascinating. It is the result, Wertheim argues, of the collapse of the logic behind the League of Nations—that world order could be anchored in the rationality of the world’s people. With Adolf Hitler’s conquest of France, “the belief that public opinion could underpin world order, appearing as a false hope since the mid-1930s, now looked like a perilous delusion.” A democratic global system, with each country being equally represented, was simply not going to work. Seeing itself uncritically as exceptional, the United States decided to take on the burden of running the world.

The important takeaway, however, is not that the United States has built an order based on an imperialist drive it hides from even itself. Instead, it’s that the creation of the prosperous order that defined the postwar era required both a breathtaking amount of self-confidence and righteousness on the one hand, as well as a kind of abandonment of idealism on the other. As Russia rises to challenge that very order, the best and brightest, unfortunately, seem to be trapped in a belief that liberal democracy is somehow self-justifying—that the system will triumph over challengers by virtue of its inherent universal truth. It’s a dangerous time for leaders to be so deluded.

— Damir Marusic

Great-power competition

Finally, Europeans, in particular, should not miss Elbridge Colby’s The Strategy of Denial. Colby served in former US President Donald Trump’s Pentagon and was one of the people who gave shape to the great-power competition paradigm. His book is a tightly argued case for why the United States must commit itself fully to countering China in the coming years. And to his credit, his argument pulls no punches as to the implications this has for US force posture elsewhere. At the conclusion of a detailed section analyzing why an even somewhat weaker NATO is more than capable of repelling a Russian invasion, he unequivocally states that the United States will not be able to provide even this lesser deterrence on its own. Europeans will have to step up in a big way. If they don’t, “the United States might very well not fill the gap in Eastern NATO left by any European unwillingness to strengthen their own defense efforts. Indeed, my argument in this book is that the United States should not plug these gaps.”

Europeans dismissing this kind of tough talk as far-fetched should not rest easy. Colby is easily one of the sharpest strategists on the right in the United States, and this is a serious and rigorous book. When Republicans eventually regain the White House, he will almost certainly be in an influential and powerful position. Don’t act surprised when the hammer comes down.

— Damir Marusic

Widening the horizon

Some might say the Europe Center is all about what happens in Europe and how transatlantic cooperation plays out in Europe. But for anyone interested in transatlantic cooperation, a book worth reading is A Vanishing West in the Middle East. French diplomat Charles Thépaut goes through the recent history of US-Europe cooperation in the region, focusing specifically on the Arab Spring and the fight against ISIS and Iran. The author makes the case that deep changes in US foreign policy, Europe, and the Middle East call for resetting the transatlantic relationship in this region. While the Biden administration is about to release its new National Security Strategy, which is expected to confirm the United States’ lessening interest in the region, this reading is worth the time to better apprehend how transatlantic cooperation might play out in this new strategic environment.

— Marie Jourdain, visiting fellow at the Europe Center

Military ethics across the Atlantic

The French Brigadier General Benoit Royal (ret.), once president of the International Society for Military Ethics in Europe, authored L’éthique du soldat français. Based on many testimonies of soldiers in operations, his work aims to present the French military’s pattern of ethical behavior as a result of their national strategic culture. He also exposes concrete cases of soldiers’ faults and offers recommendations to avoid such mistakes repeating themselves—such as making the case for respecting an adversary’s dignity to suppress the likelihood of revenge. But the main reason I recommend this reading is for his comparison of military ethics among France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Whenever I engaged American or British colleagues, I thought this book initiated me to better understand them. As an example, even though we might use the same vocabulary, the meaning of words like “victory” or even “adversary” might differ across borders or seas. Such readings thus have the merit to facilitate common understanding and cooperation across the Atlantic.

— Marie Jourdain

Widening the lens

As we work on transatlantic relations, it’s important for especially Europeans to understand structural changes taking place in the United States. Where there’s no clear answer, it may be useful to look at it from a broader, more speculative perspective, similarly to what philosopher Immanuel Kant sketched out in his short piece entitled “What is Enlightenment,” questioning the very meaning of his era.

— Petr Tůma, visiting fellow at the Europe Center

Socioeconomic cycles

George Friedman’s The Storm Before the Calm, released in 2020, represents such an effort to understand the United States. While Kant focused on what made his time different from previous periods, Friedman points out more to the continuity between now and then. Friedman identifies two major cycles in US history: institutional (about eighty years), and socioeconomic (about fifty years). Each period begins with a problem generated by the previous cycle and creates a new institutional or socioeconomic model that strengthens the United States. Understanding these cycles should help readers comprehend the current situation in the United States. For Friedman, the present moment is unique due to the collision of both cycles’ crises, which never happened before, and is the source of problems today. However, he also argues that there’s a chance the United States will rise and lead again once it invents a new institutional and socioeconomic model. Importantly, he offers concrete proposals on how to achieve that state.

— Petr Tůma

Transatlantic drift

In parallel with Friedman’s book, I read Bruno Maçães’s History Has Begun, also released in 2020, which is a provocative and inspiring portrait of the United States’ continuing drift from Europe. Like Friedman, Maçães perceives today’s crises in the United States as a chance for renewal and even an opportunity to fully realize the country’s potential as never before. Unlike Friedman’s cyclical, almost rollercoaster-like view of US history, Maçães’ interpretation follows a more linear development of what is most proper for the United States: the gradual abandoning of reality—thus also the European project of the Enlightenment—for the sake of virtual. Maçães offers a genealogy of this escapism where fiction and dreams are taking over reality, from initially going West through the movie and television industry, to exploring Silicon Valley products. Trump’s election, then, appears as a less surprising stand on this road. Towards the end of his book, Maçães outlines a new political philosophy that is more compatible with the American way of life more than John Rawls’ liberalism. Although his theory is well-considered, I would oppose the basis of some of his proposals as missing sufficient safeguards against authoritarianism. Still, the book is an example of what thinking means. Only this kind of reflection could one day offer much-needed fresh approaches to today’s multiple crises, be they political, economic, or medical.

— Petr Tůma

The illiberal moment

The third book I’d recommend is The Light that Failed: A Reckoning, released in 2019 by Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes. It is an attempt to analyze the current illiberal revolt from a historical perspective. They focus on three different cases: Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, and the United States. The book is built around the concept of imitation, seen as a key vector of political, economic, and social post-Cold War life. In Central Europe, the mot d’ordre was to westernize by means of imitation. There was no need, creativity, or space for an alternative to an all-pervading liberal order. Yet, it did not go as expected. Few leaders in the region—feeling the inherent moral inferiority of imitators towards the imitated—began to look for their own project. Hence Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s transformation from a reformist to the forerunner of the illiberal crowd, whose “successes” now have eager imitators even in the West. Russia went through a different path, the authors show, although the imitation prism also appears pertinent. Moscow was simulating the imitation, mimicking the West to get time to consolidate on its terms. Now, even the Kremlin’s “democratic charade” is over, with openly hostile policies towards the West. If imitation was progressively refused in part of Central Europe and Russia as bad for them and good only for the imitated, Krastev and Holmes show that Trump’s United States likewise rejected it as bad for the imitated. Imitators—above all China—are threats because they are trying to replace the model they imitate. The outcome, claim Krastev and Holmes, will depend on how liberals will sober up from the end of the age of imitation.

— Petr Tůma

Liberty and justice for all

I recommend Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. This may seem an odd choice, as it covers not foreign affairs nor the US role in the world (and was written in 2018). But David Blight’s masterful biography of the great abolitionist deals with themes central to American identity, both in history and, sadly, today. Is the United States a white man’s country? Or is it, as Abraham Lincoln put it, a “new nation” united by the creed of the Declaration of Independence that all are created equal? Are the deep flaws of the United States, with slavery and its legacy first among them, fatal to the higher aspirations and ambitions of the country, or can they be overcome? Debates over the US role in the world mirror this debate over the nature of the American nation. A nation whose core identity is not based on blood and soil or on an ideal of human equality will take that view to the world and seek out and support democracy. A nation that is not merely ethnically based but racist may have another view of its role in the world. US President Joe Biden speaks of democracy as an organizing principle for the United States in the world; Trump spoke of power and muscle.

In Blight’s telling, Frederick Douglass initially held to the conviction of abolitionist (and Douglass’s early mentor and supporter) William Lloyd Garrison’s view that the United States is irredeemably corrupted by slavery; that its Constitution reflects that corruption; and that moral regeneration that starts with a rejection of politics is the only way forward. But Douglass came to hold a different position: that the initial promise of the Declaration of Independence could overcome the evils of American practice; that the US Constitution was cautious but ultimately a freedom document; and that politics could redeem the United States. In this, Douglass’s thoughts went in parallel with Lincoln’s. In the most stirring chapters of the biography, Douglass the abolitionist and Lincoln the anti-slavery (but careful) politician follow converging paths that lead to emancipation, the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery, and a redefinition of the United States as a country that to be true to itself must realize freedom for all its citizens.

Douglass lived long enough to see the promise of a multi-racial American democracy destroyed by “redemption,” the restoration of white supremacy in the South as the Republican Party turned away from Lincoln’s vision. But, in Bright’s biography, Douglass emerges as an American prophet and founder, needed for this time as well.

— Daniel Fried, Weiser Family distinguished fellow

Kissinger’s ambiguous legacy

Former French Ambassador to the United States and Atlantic Council Distinguished Fellow Gérard Araud published a fascinating biographical essay on Henry Kissinger. Henry Kissinger: Le diplomate du siècle is a meditation on the work of the diplomat. It is also a reflection on Kissinger’s European roots and how the Holocaust may have influenced him before becoming former US President Richard Nixon’s Secretary of State. Still, I am more ambivalent about Kissinger’s realism than Araud. When does realism become a static conservatism that underestimates the need for potential for change in the system? Was Kissinger a realist when he advocated détente with the Soviet Union, treating it as a durable element of the international system when said union would collapse just fifteen years later?

— Benjamin Haddad, senior director of the Europe Center

Napoleon’s grand strategy

The year 2021 was the bicentennial of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death. Like many Frenchmen, I have a complex relationship with the divisive legacy of Napoleon. Napoleon by Jacques Bainville, published in 1931, is the most impressive biography I have read of him. With a focus on the geopolitics of the French Empire, Bainville argues Napoleon was trapped into an inescapable logic of war to protect the conquests of the French Revolution, most notably Belgium, which was a constant source of conflict with Britain.

— Benjamin Haddad

Within the pale

The Brothers Ashkenazi by Israel Joshua Singer is a moving novel about two Jewish brothers in the Polish city of Lodz. It covers an impressive span of time, from the Industrial Revolution to World War I. Like Warsaw’s POLIN Museum, it chronicles the story of Poland itself through the eyes of its Jewish community.

— Benjamin Haddad

The human condition

What exactly separates humans from machines? I won’t spoil the plot of Kazuo Ishiguro’s beautiful novel Klara and the Sun, which is about artificial intelligence. Yet, I was particularly struck at how it resonated in a time of COVID-19 and lockdowns.

— Benjamin Haddad

The crushing American epidemic

I come from Salt Lake City, Utah, a town within a state ravaged by the opioid epidemic. My friends are always shocked when I tell them it takes two hands to count the number of people that I know personally who have died from opioid addiction. Because this issue hits so close to home, I wanted to understand how and why we got here. Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty by Patrick Radden Keefe is gripping non-fiction that reads like a novel—it recounts the history and story of the Sackler family, who bought Purdue Pharma, created OxyContin, and then relentlessly marketed and sold it across the country. It talks about the addictions, deaths, money, and subsequent lawsuits that brought Purdue Pharma (and, just recently, the Sacklers) to justice. If you want to understand one of the most important topics facing the country today, read this book; Radden-Keefe is a master of his craft.

— Rachel Rizzo, nonresident senior fellow at the Europe Center

Momentum and change

I remember the 2008 election of Barack Obama as US president with a kind of vividness that sometimes surprises me. I was a junior in college, barely twenty-one, and the excitement pulsing through the University of Utah campus was palpable. His election awakened a generation of young people who wanted to be civically engaged, to be a part of something bigger than themselves, and to serve their country. A Promised Land, a memoir by Obama, recounts the majority of his first term and offers in-depth looks at the debate around health care, the financial crisis, the killing of Osama bin Laden, and more. Of course, no president is perfect, and for those of us who look at the Obama presidency as the years of our political awakening, this book offers insights that will both temper and reaffirm existing beliefs.

— Rachel Rizzo

Further reading

Thu, Aug 5, 2021

Here’s what we’re reading this summer

New Atlanticist By Andrew R. Marshall

Even in the depths of summer, our deeply thoughtful (and widely read) staff at the Atlantic Council keep their mental gears churning. Here are some summer reading suggestions from us for the beach, mountains, or backyard.

Wed, May 12, 2021

Reading list: Central bank digital currencies

Blog Post By Niels Graham

A comprehensive collection of the most relevant articles on central bank digital currencies.

Thu, Dec 20, 2018

Our holiday reading list

New Atlanticist By

We asked our community of experts for a list of books they would recommend for the holidays. Whether you like to read from cover to cover or between the lines, we have you covered. Stefanie Hausheer Ali, associate director for programs in the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. Follow her on […]

Image: Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel receives a book from Belgium's Prime Minister Alexander De Croo at the face-to-face EU summit in Brussels, Belgium on October 15, 2020. Photo via REUTERS/Yves Herman.