The 2022 Global Energy Agenda

The year 2021 began with high hopes for climate action, as many members of the international community—including, once again, the US—rededicated themselves to the effort and looked to deploy resources accordingly. And there were certainly landmark achievements: the Global Methane Pledge was launched, the Paris Agreement rulebook was completed, and the private holders of $130 trillion in assets under management pledged their collective financial muscle to the fight against climate change, among other victories. But as global economic demand roared back from its pandemic-dampened level in 2020, energy supply failed to keep up, inflating hydrocarbon prices, driving countries back to dirty coal generation, and underscoring the challenges of the “transition” part of the energy transition. It became clear that countries will need to thread the needle between pushing for ambitious emissions reductions and keeping prices down and the lights on in the interim, all against an ever more precarious geopolitical backdrop.

With these considerations in mind, The 2022 Global Energy Agenda details a more pessimistic outlook on the promise of the energy transition, as respondents reckoned with concerns old and new. In these pages, experts offer ways forward in the face of hazards like Russian aggression, supply-demand mismatch, and a transition that threatens to leave the global poor behind. Though the pitfalls that emerged in 2021 gave many pause, this report reveals that leaders are no less determined to find solutions, and to chart a more stable and inclusive course in 2022.

Foreword

The 2022 Global Energy Agenda

By Frederick Kempe

As we begin 2022, still under the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, it may seem as though much of the world remains in a holding pattern. 2021 began with optimism but saw the continual resurgence of the pandemic, forcing world leaders to turn their attention and resources to fighting it back repeatedly. Still, 2021 was a significant year in energy and climate and much was accomplished. Crucially, global leaders were able to convene—for the first time since 2019—in Scotland at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26). And while the outcomes are to be lauded, many observers left Glasgow feeling that more could have been accomplished.

I was fortunate to attend COP26, where I participated in programming in downtown Glasgow’s Blue Zone (with the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht- Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center) and at the Climate Action Solution Centre (with the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center) at the stunning Blair Estate. In Scotland, I watched with my own eyes as world leaders—from government, industry, and civil society—recommitted themselves to addressing the global challenge of climate change and putting civilization on a path to net-zero carbon emissions by mid-century. There were reasons for optimism: the Glasgow Climate Pact, which committed to doubling global finance for adaptation; the request that each country present a more ambitious pledge at COP27 (indicating a far greater sense of urgency than before; the Paris COP had only asked for new nationally determined contributions every five years); and, of course, the ability to hold meetings face-to-face and to gather once again as a global community. However, it was clear to all that there remains more to be done and that the path to net-zero will be fraught with challenges and setbacks.

At the time, I concluded that the world is experiencing an energy transition, rather than an energy revolution, and supporting that transition will require significant breakthroughs in clean energy technologies (with commensurate investments in those technologies) and that policy changes (like putting a price on carbon) were also necessary to support the energy transition. I predicted that climate change adaptation strategies will become just as crucial as climate mitigation. Finally, I noted that geopolitical competition and cooperation between countries—especially the US, China, Russia, and India—will shape the global energy future and play as important a role as clean energy technologies and climate change itself. How the US responds to the geopolitical challenge may be shaped by the trajectory of our domestic political landscape, which—having just passed the first anniversary of January 6, 2021—seems to hang in the balance now, more than ever.

I believe that we are up to this set of great challenges, but—as always—the devil is in the details. COP26 took place against the backdrop of an ongoing energy price spike, largely focused on Europe but truly global.

These dynamics will cast a shadow over the energy transition and have the potential to cause a backlash. This backlash could have an impact that reverberates through domestic elections in any number of countries—especially since a world that lacks energy security will also be lacking in political security—and could put a damper on the global movement towards decarbonization.

The course that we chart to net-zero must be steady but also ambitious enough to meet the challenge. Energy access must remain a key priority, especially since the steps we take at this crucial moment will determine what our world looks like by mid-century. It is clear that oil and gas—especially with mitigation efforts like carbon capture, utilization, and storage— will continue to play a role in a low-carbon future.

This second edition of The Global Energy Agenda once again sets the stage for the upcoming year. We have again polled energy leaders from governments, industry, think tanks, and academia, capturing their views of the most important trends to watch and the ways in which we can work together to shape the global energy agenda. As with last year, the key indicator of how respondents answered the survey questions was, on the one hand, respondents who believed that peak oil demand had already occurred or would do so in the near-term and, on the other hand, respondents who believed that peak oil demand would not happen until 2040 at the earliest.

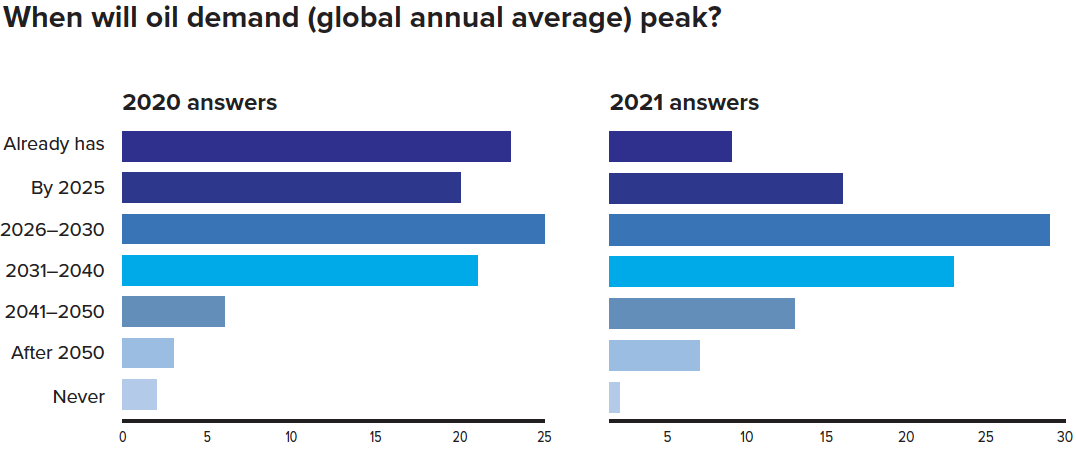

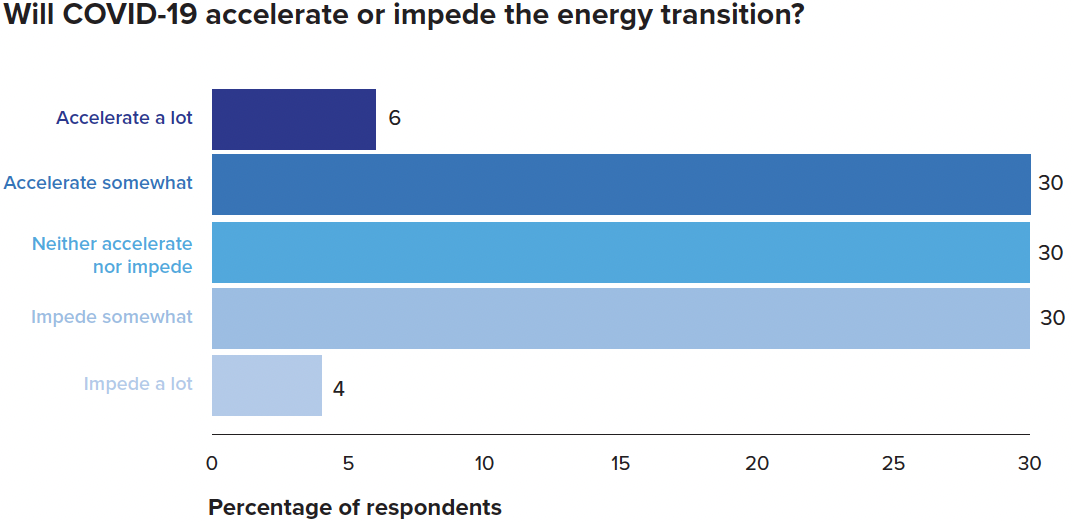

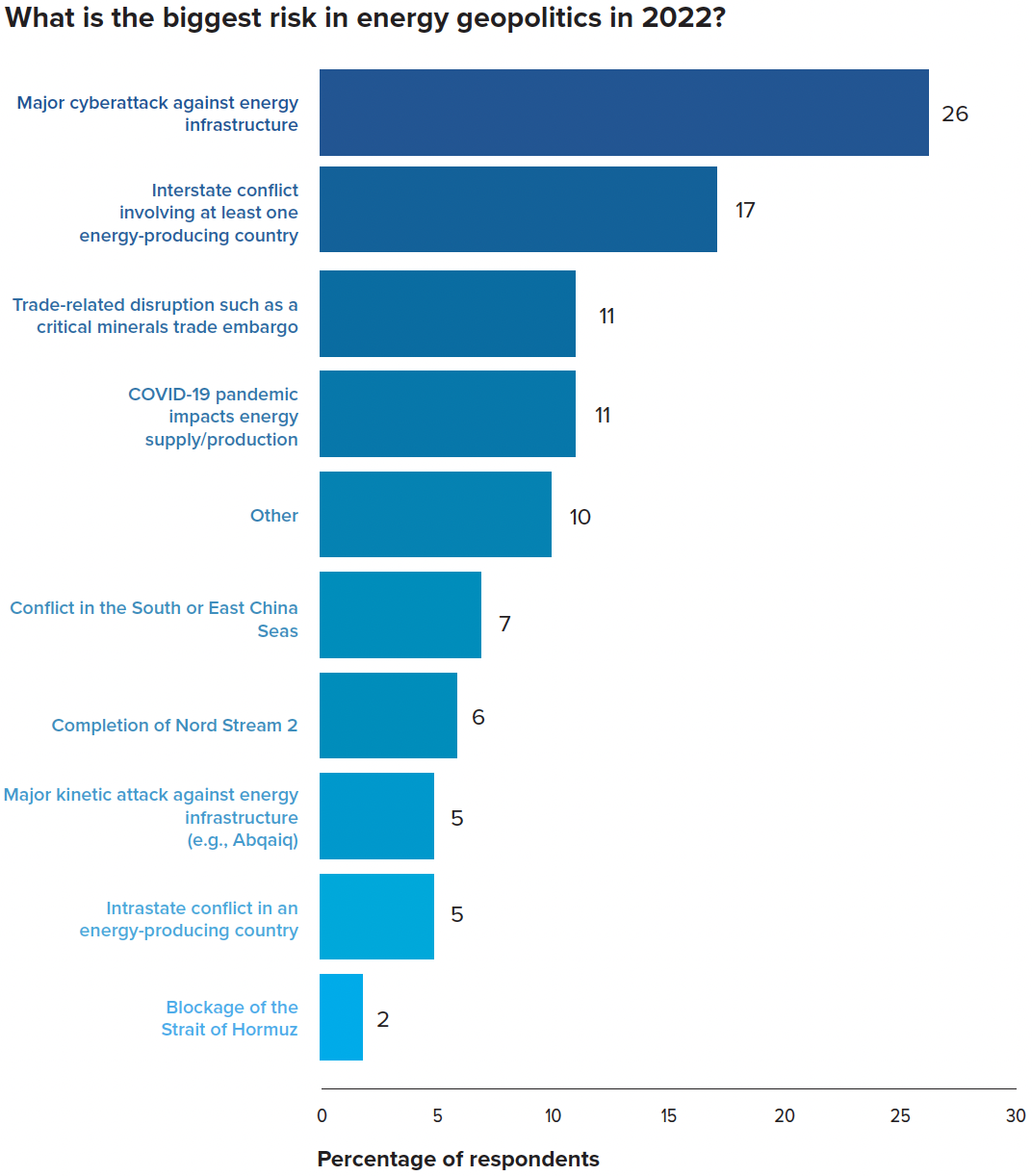

This year, there were two dramatic differences in survey answers from 2020. The first is that respondents’ prediction of when oil demand will peak shifted back by several years, suggesting they now think the energy transition is happening more slowly than they thought last year. Second, respondents’ views on the impact of COVID-19 on the energy system changed. In 2020, COVID-19 was seen as the biggest geopolitical risk to energy supply and production, but this year, cyber attacks were viewed as the greatest geopolitical risk.

As we look ahead to the coming year, I hope it is one of progress, with even greater climate commitments made at COP27 in Egypt (to be followed by COP28 in the United Arab Emirates). Furthermore, I hope this is the year when we leave the worst of COVID- 19 behind, which can only happen through the kind of global cooperation that will also be necessary to combat climate change and all of the other unforeseen challenges that this century is likely to present.

Frederick Kempe is the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Atlantic Council.

Introduction

Introduction

2021 was supposed to have been a game-changing year of climate action, with the US reentering the Paris Agreement and the pandemic recovery funds of many countries aimed at “green stimulus.”

From the finalization of the Paris rulebook to the launch of the Global Methane Pledge—and from renewal of US-China cooperation on climate to a dramatic increase in net-zero commitments from countries and companies—much was accomplished on climate over the past year. Additions of renewable power capacity likely set yet another record in 2021, and nuclear power might have turned the corner in public perception as a clean power source. Current climate pledges now put the world on track for 1.8 degrees of warming.

But it still was not the year many had hoped for or predicted.

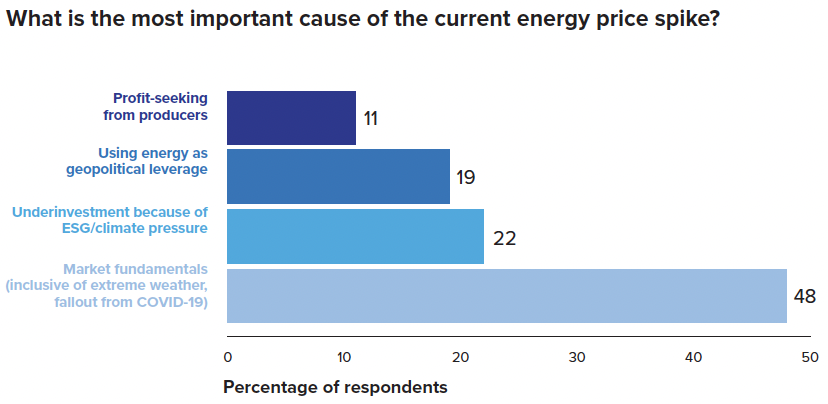

As energy demand recovered from 2020 lows, carbon emissions came roaring back and energy prices skyrocketed, becoming a major driver of inflation and proving a political headache for many global leaders. Natural gas prices in Europe, for instance, hit record highs in December. Brent crude closed the year just shy of $80 but had spent more than half of the fourth quarter above that key threshold. Even a historic coordinated release of strategic oil stocks with US, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and the UK—coincidentally timed with news of the highly transmissible Omicron variant of COVID-19—brought down prices only briefly. And coal demand, which was thought to have peaked globally in 2014, rose dramatically, signaling a possible record-breaking year in 2022. COP26 did not “resign coal to history” as COP President Alok Sharma had declared it would.

So instead of being remembered as the year when the world turned the corner on climate action, 2021 will likely be remembered as the year global leaders began to confront the challenge of managing continued hydrocarbon demand even as they push for dramatic emissions reductions.

At its most basic level, this is exemplified by the seemingly contradictory calls by the Biden Administration for OPEC and US oil producers to increase production while simultaneously encouraging climate action. But in reality, these efforts were not contradictory at all; energy demand obviously must be met in the short term, even as that demand shifts to cleaner sources in the long term. A better example, then, is the Biden Administration’s creation of the still-nascent Net-Zero Producers Forum, which aims to bring major oil and gas producing economies in line with net-zero goals. So too is the EU’s inclusion of nuclear and gas in its green taxonomy.

2021 was also supposed to have been the year that the COVID-19 pandemic ended, or at least became much more manageable. Though the year began with a winter COVID surge during which, at its worst, nearly 20,000 people globally died per day from the disease, the development of multiple effective vaccines was the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. And by mid-summer, in the developed world, the pandemic seemed to be ending.

Fast forward to December and, due to waning vaccine efficacy against infection (though still high efficacy against severe disease), a significantly more transmissible variant, and populations and politicians leery of additional lockdowns, global case numbers soared beyond anything seen over the previous two years. While severe disease and death seemed less likely

with Omicron than previous variants, hospitals again were stretched thin, and the world was only beginning to understand the economic disruption from so many people infected at once. How this will impact energy demand could be a major story for at least the beginning of 2022 and potentially for much longer.

In 2022, geopolitics will also be increasingly volatile, with Russia amassing troops on Ukraine’s border, Iran ramping up uranium enrichment, and tensions growing over Taiwan. The energy implications of these flashpoints are potentially dramatic—Russia has already been accused of manipulating the European gas market to increase prices and weaken Europe’s hand in responding to its apparent ambitions in Ukraine—bringing yet another year of disruption to energy markets.

The 2022 Global Energy Agenda and essays

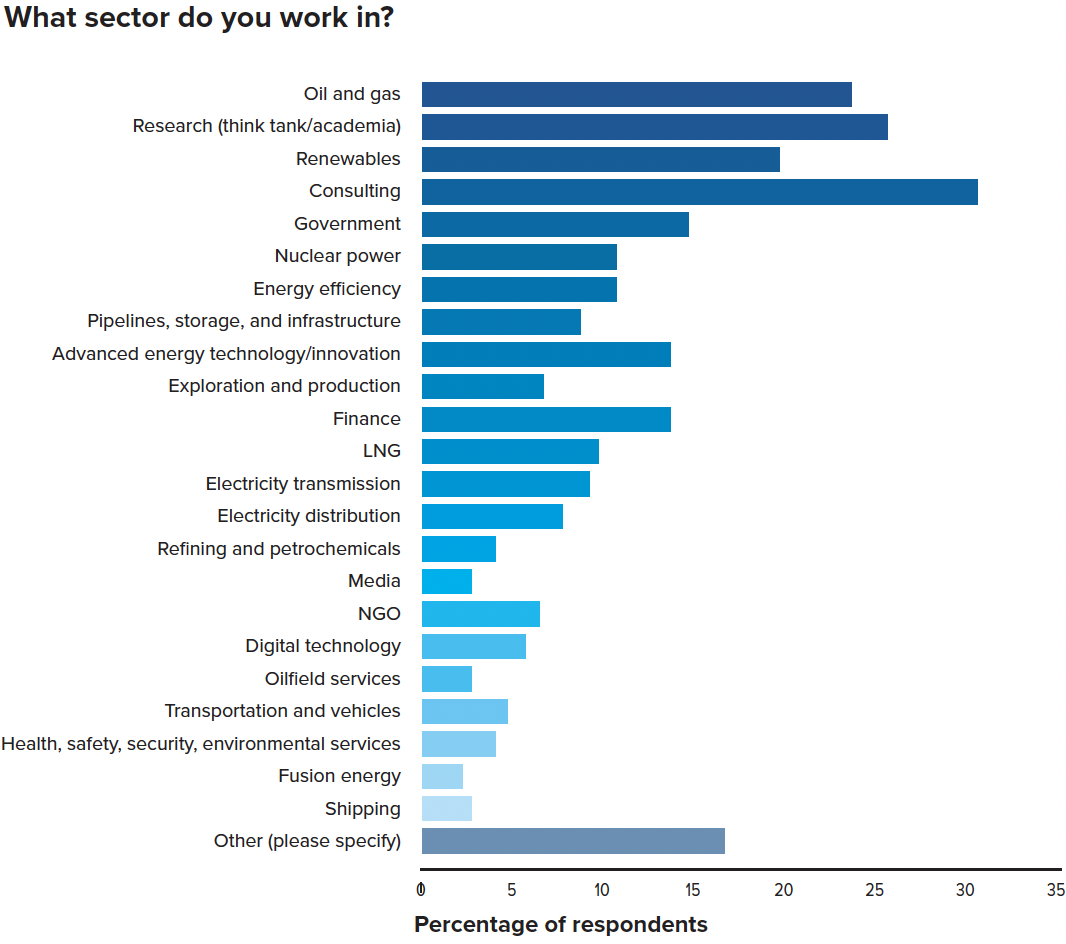

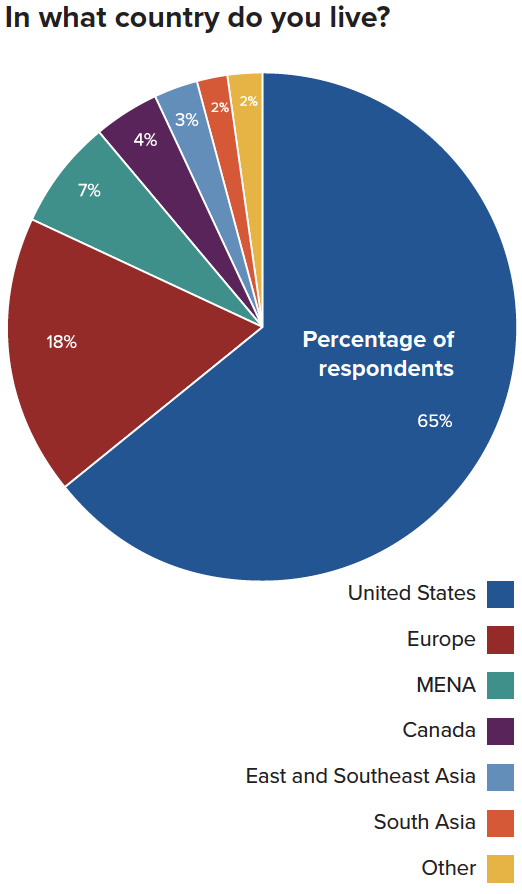

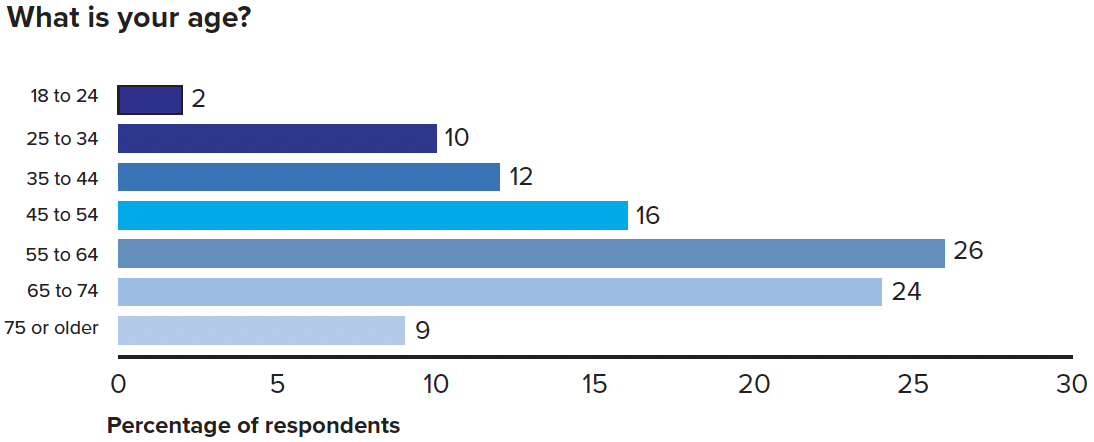

To better understand the key issues facing the energy system in 2022, the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center commissioned a series of essays from global experts, corporate leaders, and government ministers. The Center also surveyed a global group of energy leaders, asking them a dozen high-level energy and climate questions. The survey reached hundreds of experts between November 11th and December 6th, 2021, and provides a valuable look at current thinking.1

This is the second annual Global Energy Agenda survey, and the inclusion of various questions from the first survey, conducted in the fall of 2020, also provides useful information on how views are changing.

These essays are not intended to provide a uniform outlook for the year ahead in energy. Instead, through their diversity, they aim to set the terms of debate and outline what possible outcomes might look like, depending on the decisions that governments and industry collectively make.

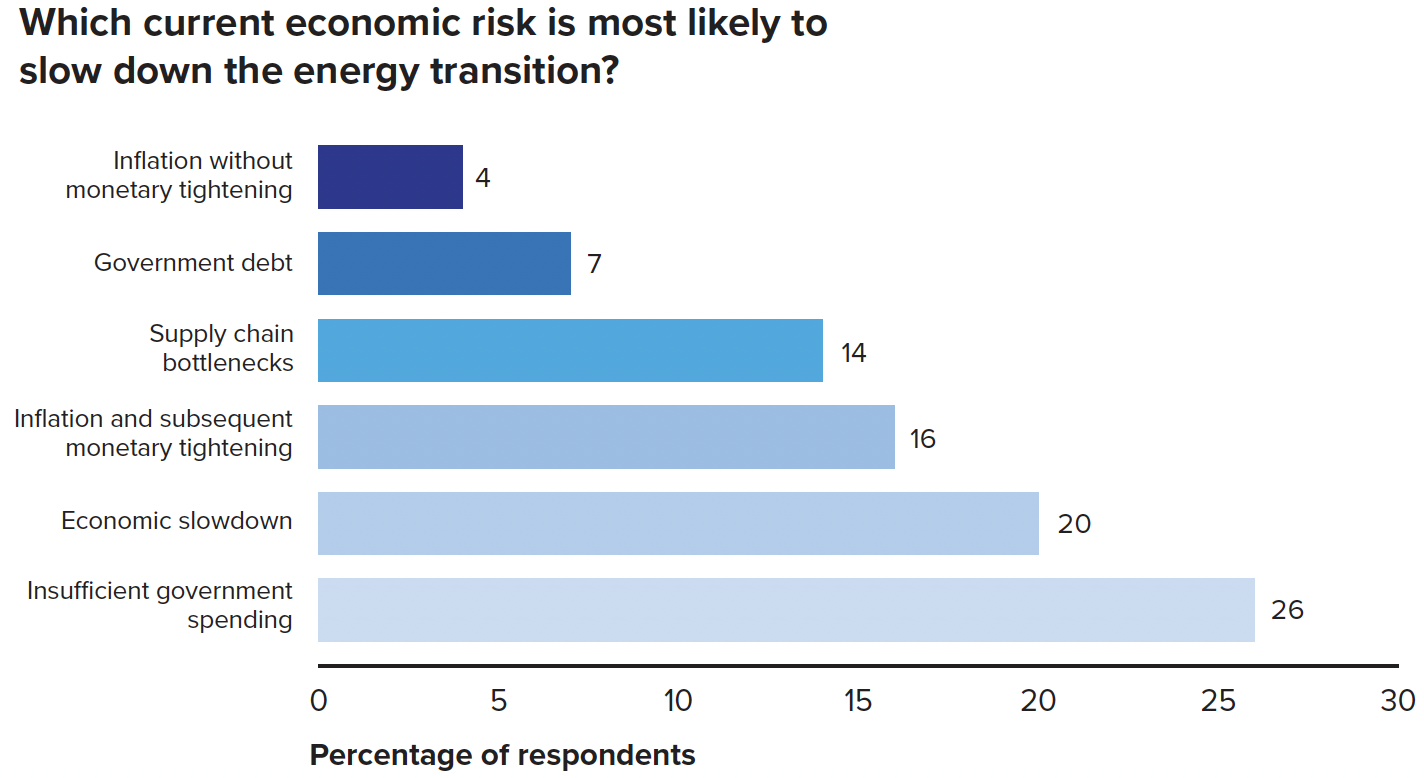

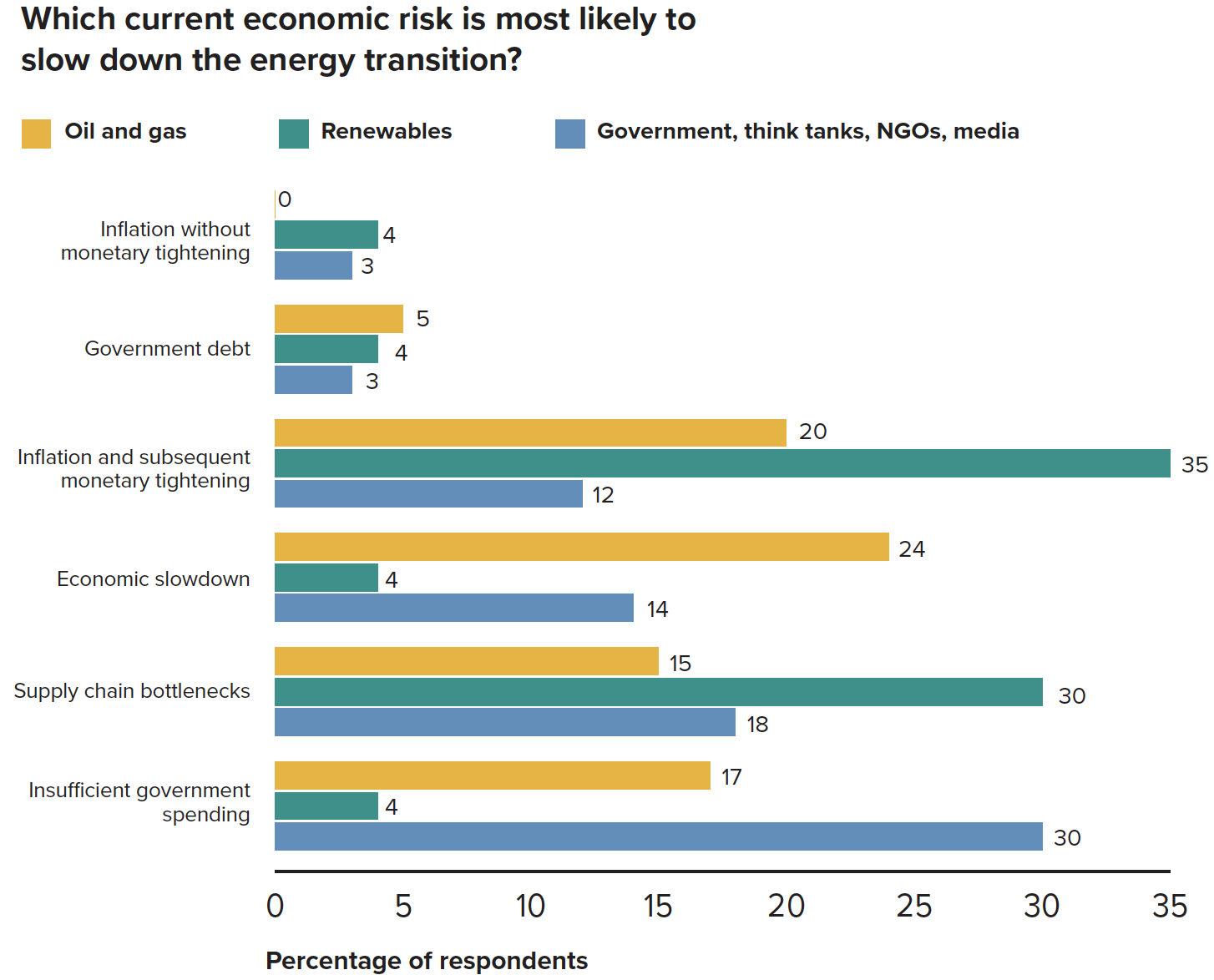

The survey results will be explored in more detail in the volume that follows. But a few key takeaways help provide overall context.

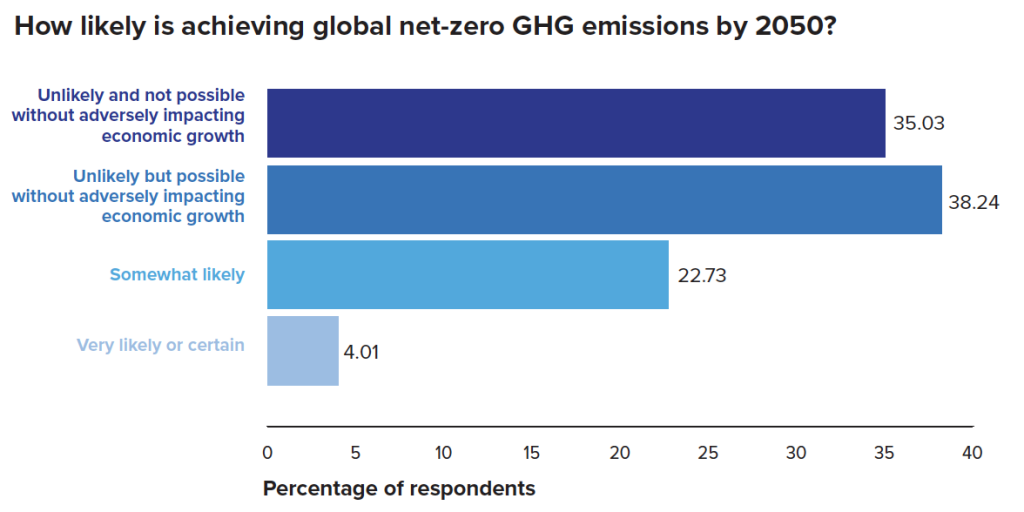

Fossil fuels will play a larger role for longer. Compared to last year, the energy sector as a whole thinks that fossil fuels will remain a part of the picture for slightly longer. This shift takes two forms. First, in our 2020 survey, respondents on average thought that peak oil demand would occur 10.5 years into the future. Among those surveyed in 2021, the figure has not declined by a year—as one might expect— but is now 12.8 years. Second, while 36 percent of 2021 respondents called the achievement of global net zero emissions by 2050 either somewhat or very likely, that figure has dropped to 27 percent in our current survey.

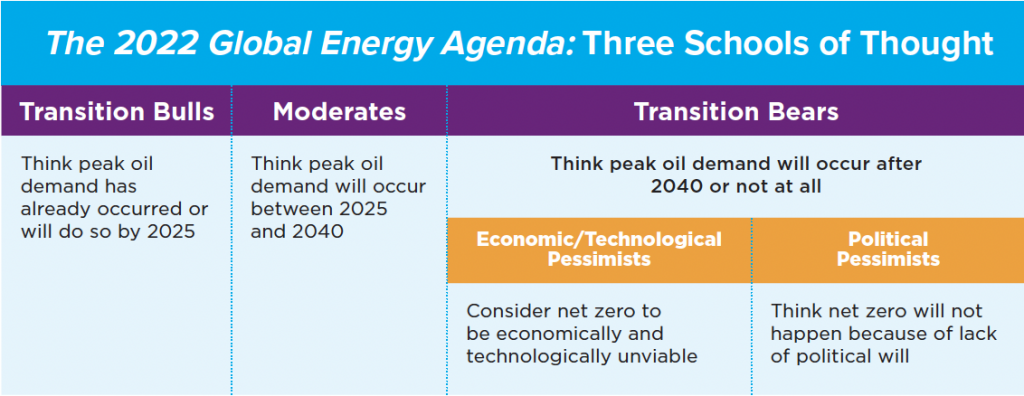

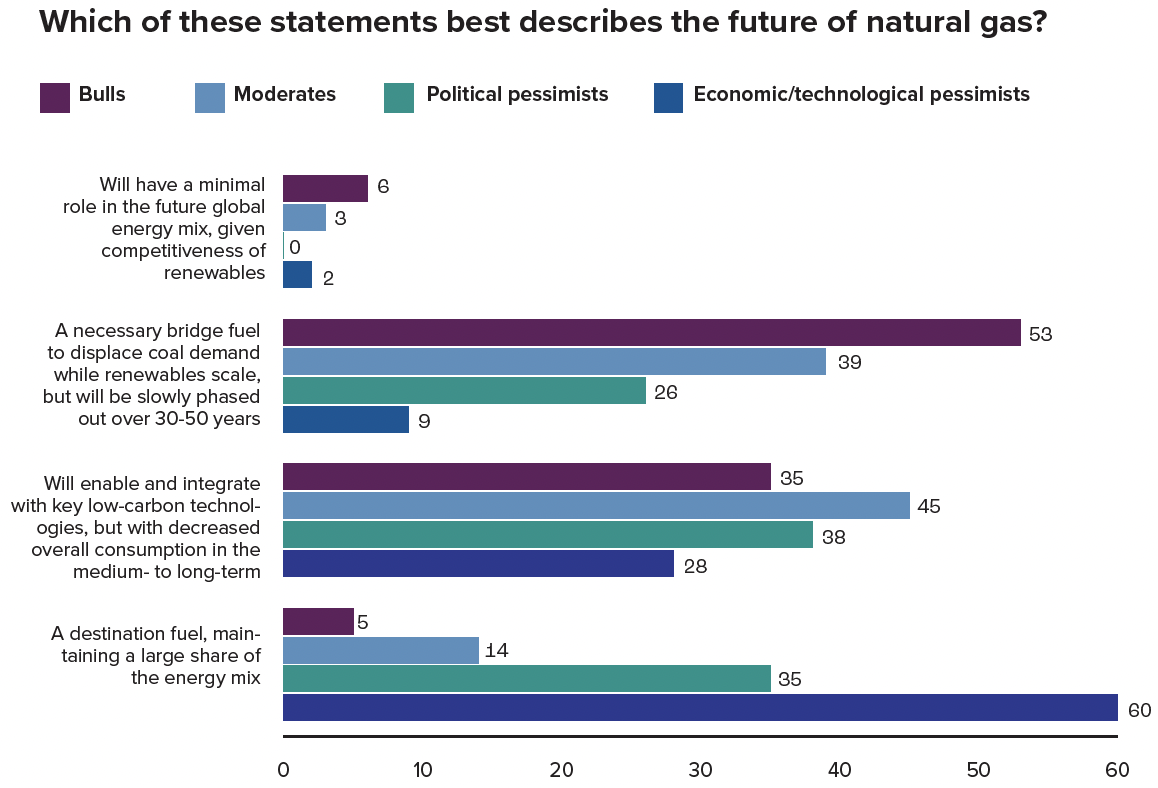

Two types of energy transition skeptics. Last year, our analysis identified—across age, geography, and, to an extent, area of activity within the sector—three broad schools of thought. The clearest marker of the group into which respondents fell was their estimate of peak oil demand’s likely date. Those we named “transition bulls” thought that this had already occurred or would do so by 2025; “transition bears” believed that it would not happen until 2040 at the earliest, if ever; and “moderates” forecast a year between 2025 and 2040.

In our current survey, the same division is apparent. This year, however, we had more “transition bears” as survey respondents, which permits more detailed analysis. We found that bears who believe that global net zero by 2050 is unlikely—and that, if reached, such an achievement would adversely affect economic growth—have answers quite distinct from fellow bears. The latter group sees political will as the largest barrier to reaching net-zero. The former group, however, largely believes that technology will not be able to deliver net-zero, making questions of policy and political will moot.

COP26 was “more blah, blah, blah.” When asked to rank the outcome of the conference on a scale from “more blah, blah, blah” to “creating a foundation for achieving global net-zero by 2050,” 51 percent of respondents chose the former and only 11 percent the latter. The rest said that it fell in between. Although Europeans and our transition bulls group were slightly more sympathetic, even among these respondents, more had a negative than a positive take.

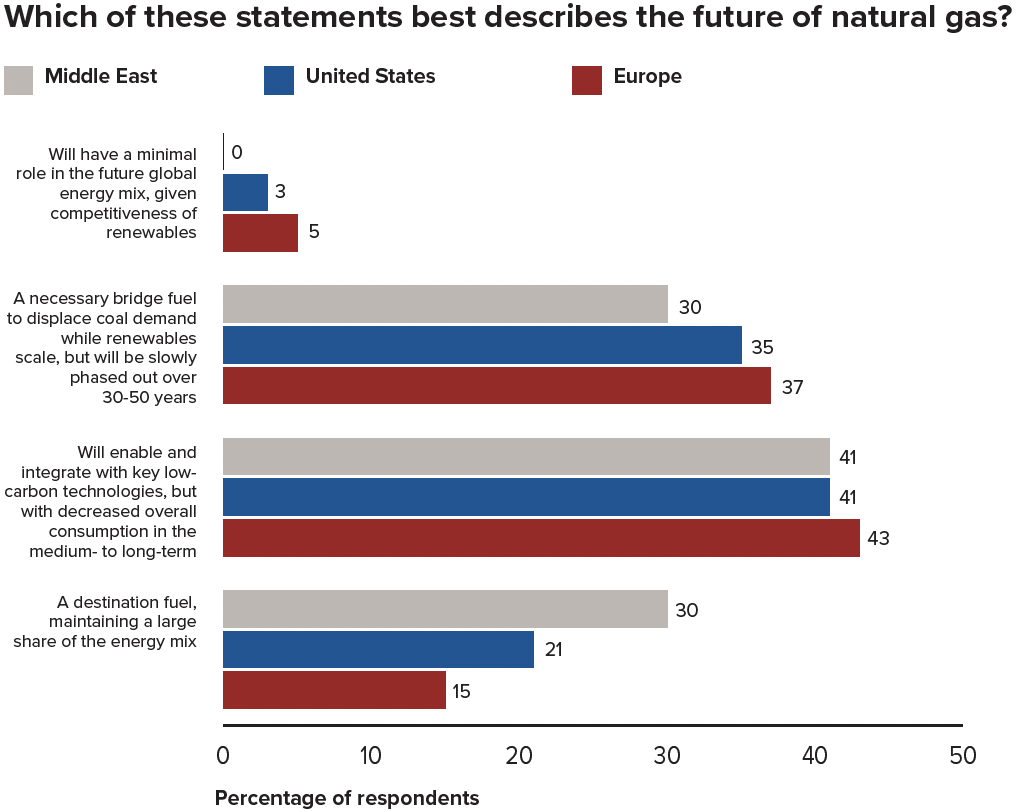

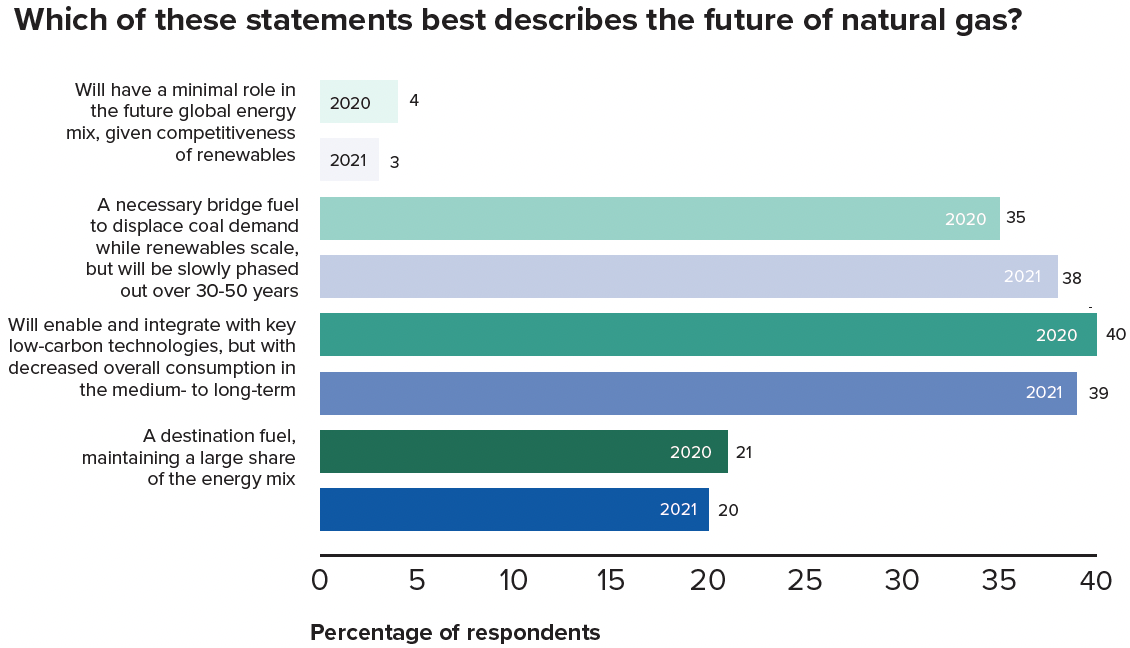

Divergence on the future of natural gas. While on average, expectations about the long-term future of natural gas appear to have changed little from last year—a substantial majority still think that it will have a long-term future—geography is starting to be a predictor of thinking. 58 percent of European respondents believe that gas has a long-term future, close to the 62 percent in the US, but well behind the 71 percent in the Middle East. More striking, while only 40 percent of bulls think that the fuel has a long-term future, 59 percent of moderates do too, even though the groups gave similar answers last year.

COVID-19 is no longer the biggest perceived risk or driver of change. Last year, 39 percent of those surveyed thought that COVID-19 was the biggest geopolitical risk to energy supply and production. This time, only 11 percent do, with cyberattacks the most frequently cited at 26 percent. Similarly, the pandemic is no longer as widely perceived as a driver of change: the proportion thinking that it will accelerate the energy transition has dropped from 61 percent to 36 percent.

Taken together, we hope The Global Energy Agenda survey responses, analysis, and essays will lay out the contours of the current energy system, assess the events and trends that will shape the energy system in 2022, inform fact-based debate and analysis about the best path forward, and set the shared energy agenda for the year.

1 Please see the Appendix for a demographic breakdown of survey respondents, including geographic, age, and employment sector.

Chapter 1: Climate change and climate action

Climate change and climate action

Essays

How voluntary use of carbon markets can help secure sustainable energy for all

By Rachel Kyte

Projecting COP ambitions across COP27 and COP28

A conversation with: H.E. Dr. Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, Rt. Hon. Alok Sharma MP, H.E. Sameh Shoukry; moderated by Frederick Kempe

COP26 did not deliver everything we wanted, but here is where key progress was made

By Fatih Birol

COP26 and the Climate Action Solution Centre

By Rt. Hon. Charles Hendry

Resource efficiency is crucial for sustainable development

By Jonathan Maxwell

Nuclear energy is essential to achieving a clean, affordable, and equitable energy system for the future

By Sama Bilbao y León

The role of nuclear power in Japan’s future energy system

By Tatsuya Terazawa

Survey results

On his first day in office on January 20, 2021, US President Joe Biden signed the documents necessary to bring the US back into the Paris Agreement. With an aggressive policy platform and significant star power in senior climate jobs, the US was “back.” And with global momentum behind climate action, renewed US leadership, and a focus on COP26, 2021 was supposed to be the year the world turned the corner on climate action. And in many ways, this was the case; by the end of the year, nearly 90 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions were covered by net-zero targets, up from about 70 percent at the beginning of the year.

However, COP26 was not nearly as successful as many had hoped (though it was not the complete failure that some say it was); “green stimulus” was not as forthcoming as had been predicted; and with energy demand roaring back from pandemic lows, emissions jumped as well. For good reason, this has left the energy and climate community in a more pessimistic mood about climate change than it had been at the beginning of 2021.

Despite continued growth in net-zero pledges from governments and the private sector, expectations about achieving net zero by 2050—already pessimistic in the previous survey—have grown more so. The proportion of respondents who think it is at all likely has dropped from 36 percent last year to 27 percent in the current survey. Meanwhile, those who believe that it is unlikely and not possible without adversely impacting economic growth have risen from 24 percent to 35 percent.

Those in renewables are a bit more hopeful: 32 percent call net zero by 2050 somewhat or very likely, but this is still a significant decline from last year when 46 percent thought so.

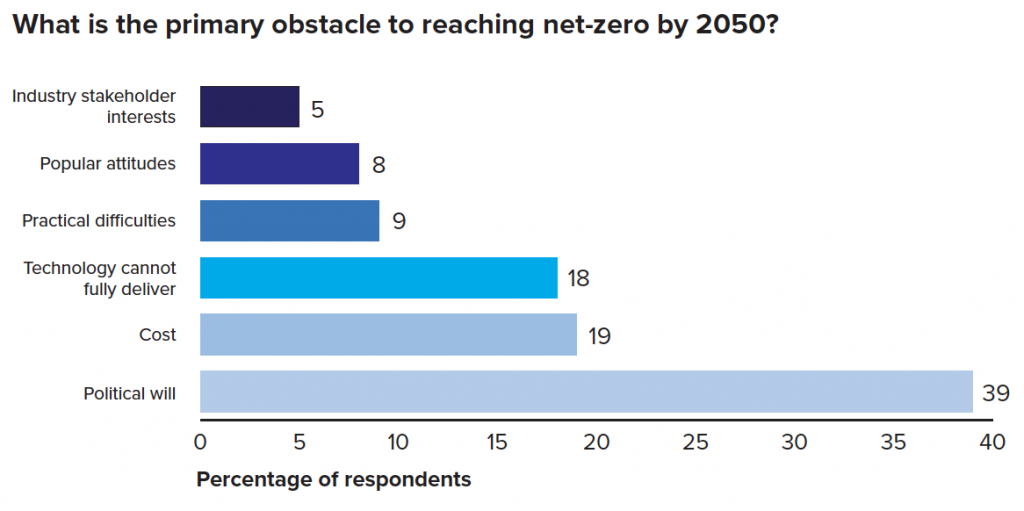

To better understand respondents’ thinking about the potential for net zero, the survey asked them to explain—in their own words—the primary barriers to reaching it. Our analysis coded these into broad categories: political will (including everything from general political will among many countries to attitudes of individual governments and international bodies); lagging technology (covering those who believed clean energy technologies could never deliver the power the world needs to those who thought demand is growing too fast for them to do so by 2050); attitudes within populations (including lack of interest, unwillingness to pay, and fear of nuclear power); energy industry pushback and entrenched interests; and the inherent difficulties of carrying out such a transformation given the drag of existing infrastructure and scope of the challenge. Some comments contained more than one of these; others, none.

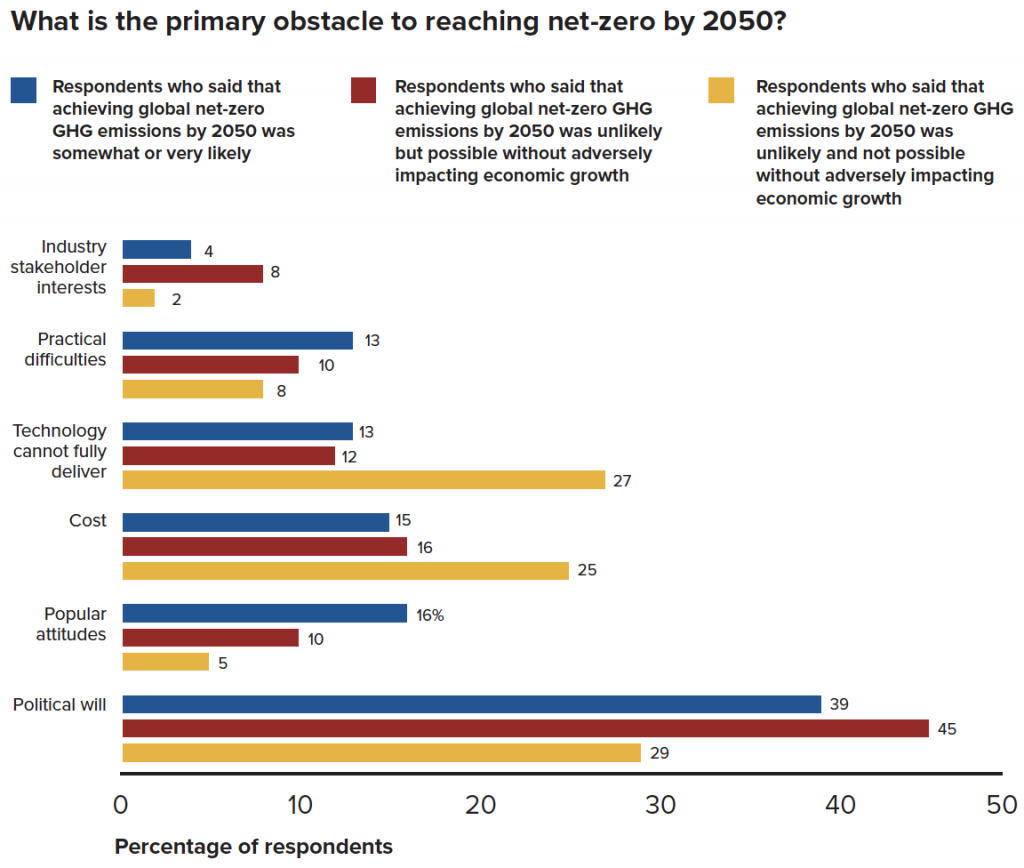

The biggest issues overall—political will and cost— come as no surprise. Far more illuminating is how views on these barriers diverge between those who see net zero as likely, those who believe it unlikely but possible with little economic cost, and those who think it unlikely and also a costly pursuit.

For those who think net zero is likely or possible without negative economic impact, political courage and vision are, by a substantial margin, the key requirements for change; the other issues pale in comparison. Typical of the comments from this group about the leading barriers to success are that they boil down to “the inability of political leadership to take bold measures with an impact only years to come” and a “lack of courage to adopt the necessary measures.”

For those who consider net zero impossible without an adverse effect on growth, political will matters, but so do prohibitive cost and an expectation that green technology will not deliver the energy needed.

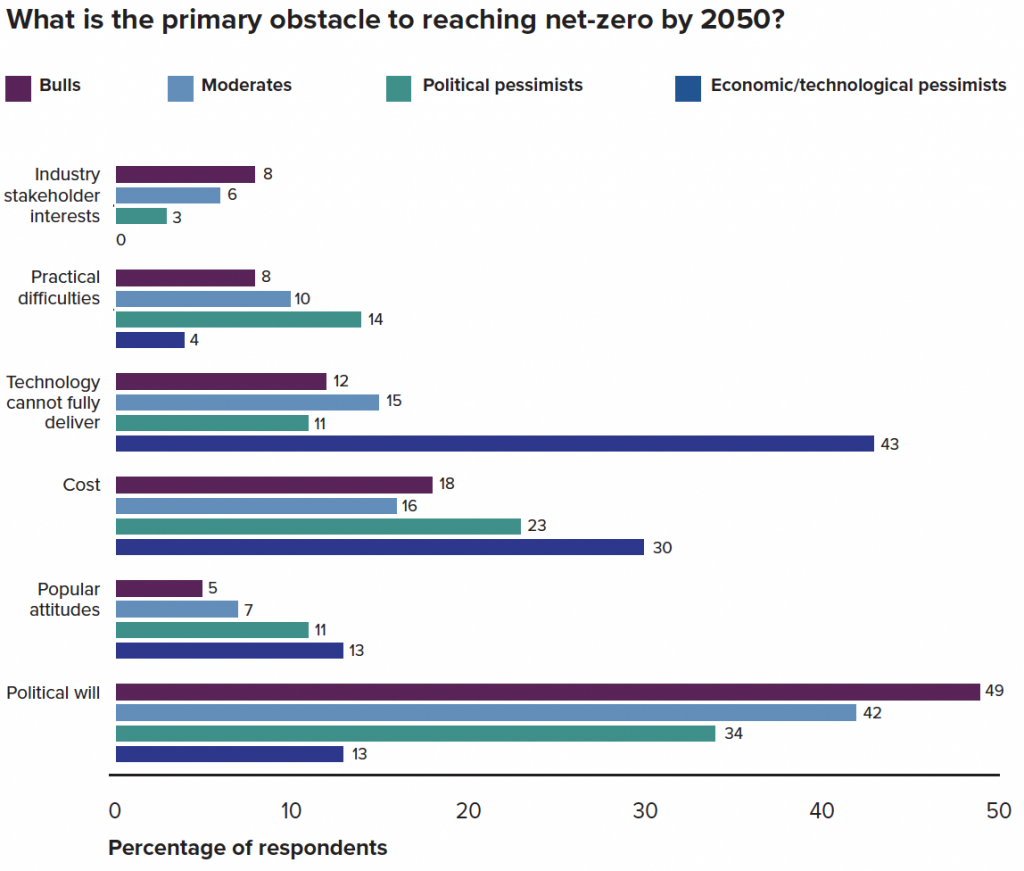

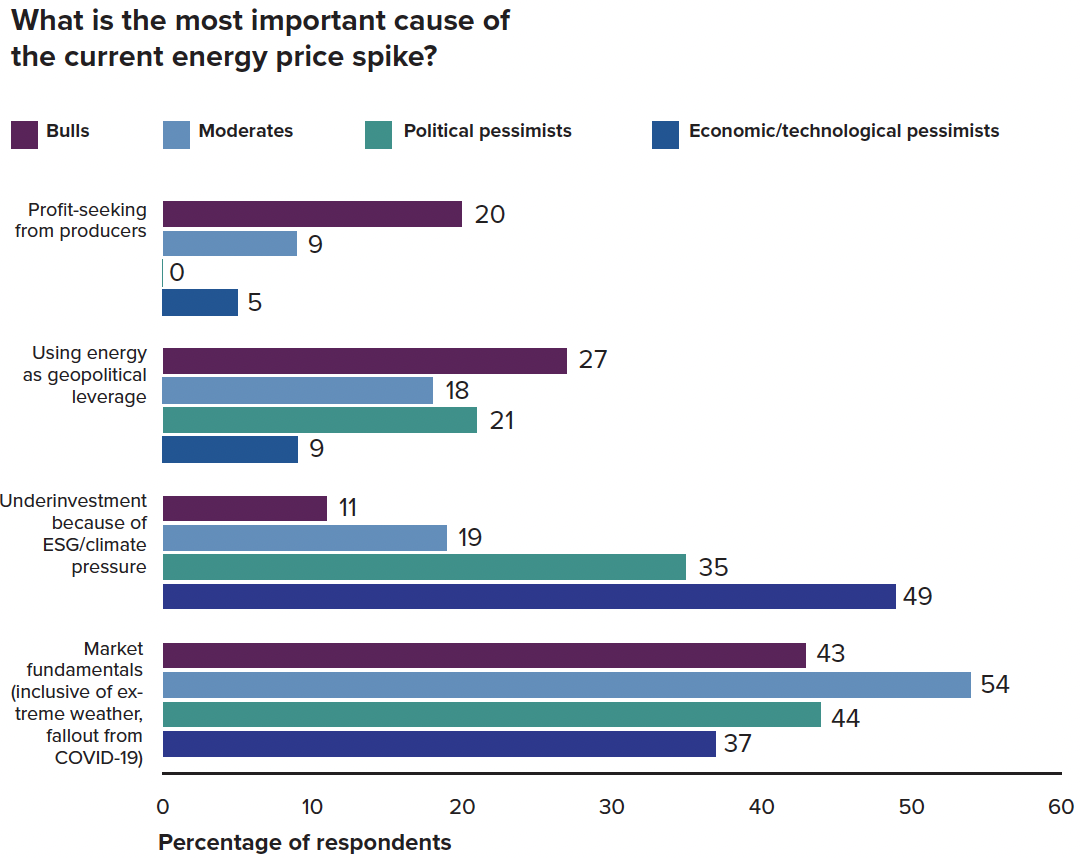

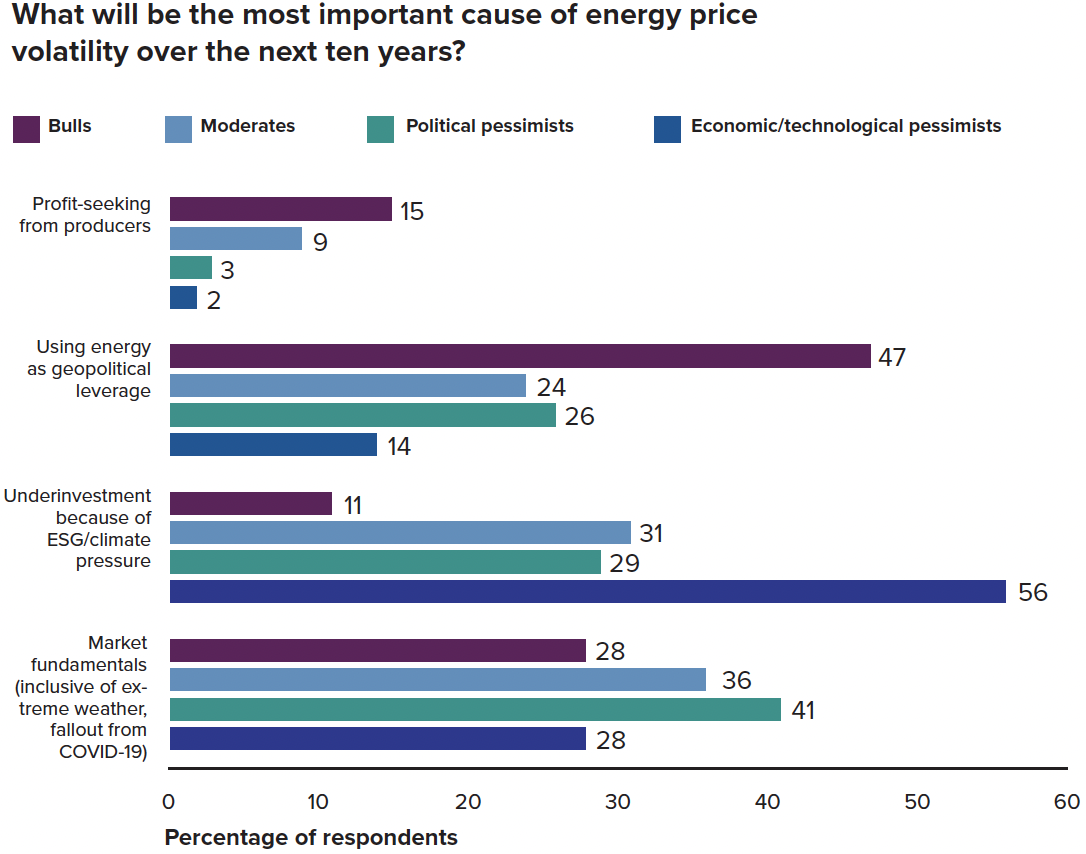

This divergence is even more pronounced when seen through the prism of attitudes toward the future of peak oil demand. The accompanying chart looks at the responses for our transition bulls, moderates, and bears, but divides the latter between two groups we call economic/technological pessimists and political pessimists, where we find a meaningful difference in the reasoning for their pessimism.

This difference— not visible in the 2020 survey because of the size of our survey sample—suggests there is one group of transition bears who consider net zero to be technologically and economically unviable (the “economic/ technological pessimists”), and another whose pessimism about the future arises from pessimism about human, especially political, behavior (the “political pessimists”).

The political pessimists differ little from the transition bulls and moderates on barriers to net zero. Economic/technological pessimists—who make up 13 percent of the entire respondent pool—operate on fundamentally different premises. For them, political will is almost irrelevant. Oil and other fossil fuels will have staying power because clean technology is unlikely to deliver the goods; politicians who try to bring about change in such an environment will not be far-sighted leaders but more akin to King Canute ordering tides. As one respondent put it, the key barrier is “the reality that fossil fuels are abundant, reliable, affordable, and proven for economic development, and renewables cannot substitute for them.” Or, as another said more succinctly, “we need fossil fuels to run economies.”

In line with the optimism at the beginning of 2021, many leaders pinned their hopes on COP26. For instance, in May, COP26 President Alok Sharma said, “The days of coal providing the cheapest form of power are in the past … So let’s make COP26 the moment we leave it in the past where it belongs.” Of course, COP26 was far more of a mixed bag, with parties declaring a “phase down” instead of a “phase out” of coal, for instance.

It is at least fair to argue that there were significant accomplishments at COP26, and that expectations were simply set too high. Our 2020 respondents certainly were skeptical heading into the COP. For example, only 11 percent thought that the meeting would achieve a consensus on global carbon trading under Article 6 of the Paris agreement. Here Glasgow exceeded expectations, with the relevant rule book now finalized. In her essay on carbon markets, Rachel Kyte, dean of the Fletcher School and former CEO of Sustainable Energy for All, addresses how voluntary carbon markets can complement future Article 6 markets and can be used to fund clean, distributed energy in regions that are most lacking, especially sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

2 We do not do this for the bulls and moderates as it reveals no meaningful differences.

How voluntary use of carbon markets can help secure sustainable energy for all

By Rachel Kyte

In 2021, the debate around whether voluntary carbon markets would support or delay urgent climate action came to a head due to countries’ increasing and unmet needs for financing and an unprecedented surge in private sector net-zero commitments, including those by the financial sector.

The long-overdue agreement on the Article 6 rulebook at COP26—rules for international carbon markets—provides renewed confidence that carbon credits may play a credible role in decarbonizing the global economy.

But there is much work to be done to ensure that carbon markets are purposeful, i.e., that they reduce emissions and share the benefits with those who have rights to land, sea, and resources. 2022 is crucial in reaching an agreement on achieving integrity in the voluntary use of carbon markets and ensuring the revenues can be used for resilience and speeding energy transitions.

This trajectory for carbon markets opens opportunities for the energy sector in two ways. First, firms can use carbon credits above and beyond decarbonization as part of their transitions, demonstrating credibility. Secondly, voluntary carbon markets can open funding flows to enable clean energy infrastructure in developing economies.

We will only realize these opportunities if we build carbon markets on a foundation of inclusivity and integrity. Inclusivity and integrity are end-to-end prerequisites and will be equally important for those who supply the carbon credits and those who buy and make claims based on them.

Opening up new finance flows to accelerate energy access

Despite early voluntary carbon markets and the Kyoto Protocol Clean Development Mechanism’s focus on renewable energy, over the last few years, voluntary carbon markets have, for the most part, become synonymous with offsets based on protecting and restoring nature.

But, given that projects to generate credits in a high-integrity market must be additional—meaning they would not happen without finance from carbon credits—opportunities abound in the energy sector. In particular, carbon markets could bring a much-needed revenue stream to scale distributed renewable energy infrastructure that might not yet be commercially viable, including those that serve the bottom of the pyramid (for example, scaling the distribution of clean cookstoves). There has been plenty of innovation and experience in the last several years on which we can build.

In my previous role as CEO of Sustainable Energy for All, I saw firsthand the transformative impact of energy access, the resilience that distributed renewables and clean cooking solutions build, and the impact of these efforts on women’s leadership roles within society. Amid the pandemic and with extreme heat on the rise, energizing health systems, reaching the poorest through safety nets with bundled energy and clean cooking, and ensuring access to sustainable cooling are essential elements of resilience in the climate crisis.

We know those without energy are predominantly women in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, either living beyond or below the power lines of expensive, low-performing grids. SEforALL and Climate Policy Initiative’s finance tracking published in Energizing Finance reports shows that despite international pledges, the funding for decentralized renewable energy and clean cooking is still too little and too slow for the task at hand. And it is still not a domestic funding priority for many governments. Voluntary use of carbon markets may provide a timely new revenue stream.

Putting voluntary carbon markets on a runway to regulation

While voluntary carbon markets are separate from future Article 6 carbon markets, the newly agreed-upon rulebook establishes guidance to deliver carbon trading aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Therefore, voluntary use of carbon markets cannot undermine the goals of the Paris Agreement and the future Article 6 market that stems from it.

Put another way, voluntary carbon markets can form a runway to regulation and may become part of—or be closely aligned with—future Article 6 carbon markets. How long a runway depends on leadership from governments in putting effective carbon pricing in

place and on initiative from stakeholders committed to forming high-integrity markets.

The Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI) aims to establish guardrails for private sector climate action claims, like “net-zero,” “climate-neutral,” or the many variations on that theme. These claims will need to be aligned with the Paris Agreement, meaning that carbon credits are being used above and beyond action to meet a science-based abatement pathway. In short, carbon credits must not replace, delay, or obscure decarbonization.

The first step in establishing these guardrails will come in April 2022 when VCMI publishes draft practical claims guidance for firms on how and under what circumstances they should use carbon credits and the claims they can credibly make about this use.

At the same time, we must ensure that rightsholders are at the core of the design and regulation of these markets. The onus to deliver this is not just on project managers or regulators; firms that use carbon credits are accountable for what happens on the ground.

Decarbonizing energy systems that work for all is critical for sustainable development. As we move along the runway to regulation, high-integrity, voluntary use of carbon markets may smooth the shift to clean, affordable, and reliable energy systems for everyone.

Rachel Kyte is dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University and previously served as special representative of the UN secretary-general and chief executive officer of Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL).

Agreements on coal and methane were among the other outcomes, although the strength of these agreements, and the extent to which states are likely to adhere to other long-term commitments made at the meeting, remain up for debate.

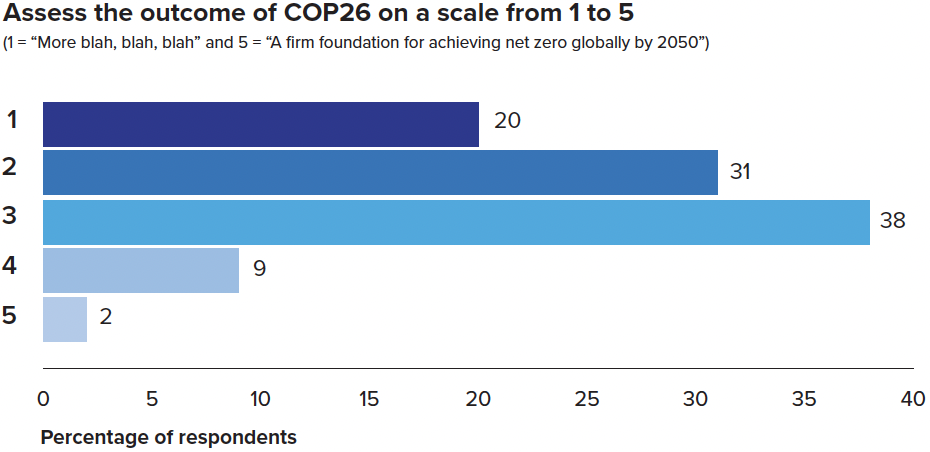

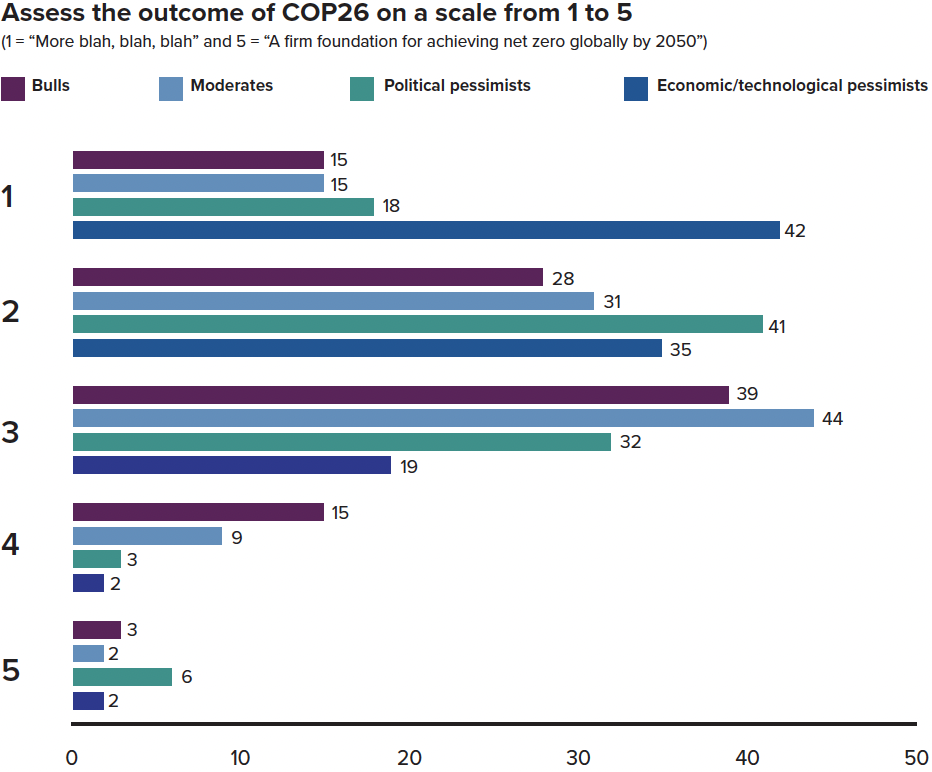

Overall, this year’s survey respondents do not appear to consider COP26 to be an impressive milestone toward a new energy future. We asked them to assess its outcome on a numeric scale where one described the event, per Greta Thunberg, as “more blah, blah, blah” and five indicated that COP26 created a “firm foundation for achieving net-zero globally by 2050”.

The assessment was noticeably more negative than positive. Over half (51 percent) characterized the outcome of COP26 as yet more blah, blah, blah. Most of the rest (38 percent) put it half-way between the two choices, and just 11 percent considered it a solid foundation.

In every subsection of the energy sector that we look at in this analysis, those with a downbeat assessment outnumbered those who saw the progress as substantial. Two groups that were less negative, however, are worth noting.

First, European respondents were noticeably more sympathetic to the results of the meeting. More than one in five (22 percent) answered with a four or five on our scale, and only 35 percent rated it toward the “blah, blah, blah” end. This is still an overall negative result, but it contrasts sharply with the US respondents of 9 percent and 55 percent respectively. Results from the Middle East respondents—15 percent and 44 percent—were somewhere in between.

Secondly, attitudes about the future of fossil fuels and carbon also have a marked impact on assessing whether a result—which conventional wisdom deems largely mixed—represents progress or hot air. As the chart shows, there is a noticeable difference in how positively our transition bulls, moderates, and bears see the outcome of COP26. For our transition bulls, while not everything they hoped for, 18 percent believe that Glasgow represents more of a firm foundation for progress than yet more talk of little consequence. Among the economic/technological pessimists, fully 77 percent characterized it as “blah, blah, blah.” Presumably, a greater belief that these efforts can make a difference increases the sympathy of those judging their value.

Regardless of one’s take on COP26, there is a tremendous amount of work to do. Our essay contributors provide a number of ideas for immediate and long-term action.

First, in an interview moderated by Atlantic Council CEO Fred Kempe during Abu Dhabi Sustainability Week, COP26 President Alok Sharma, COP27 President and Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry, and UAE Special Envoy for Climate Dr. Sultan Al Jaber lay out their vision for how to build on COP26 to have success at COP27 in Egypt and COP28 in the UAE.

Then, International Energy Agency (IEA) Executive Director Fatih Birol provides his take on COP26, which is far more positive than negative, and outlines several key actions the IEA is taking to accelerate progress on net zero.

The Rt. Hon. Charles Hendry, former UK Minister of State for Energy at the Department of Energy and Climate Change, discusses conversations that happened on the sidelines of COP26 at the Climate Action Solution Centre, where a group of global stakeholders gathered for 12 days to discuss crucial climate issues that could not be addressed under the auspices of the COP.

Jonathan Maxwell, the CEO of Sustainable Development Capital, follows up with a deep dive on energy efficiency, a crucial topic we discussed at CASC but that gets short shrift in international climate conversations.

Finally, Sama Bilbao y León, the Director General of the World Nuclear Association, discusses the importance of nuclear power in meeting net-zero goals; and Tatsuya Terazawa, Chairman and CEO of the Institute for Energy Economics Japan, takes a look at nuclear power in Japan and the complicated role it plays in Japan’s net-zero ambitions following the Fukushima Daiichi accident.

Projecting COP ambitions across COP27 and COP28

A conversation with: H.E. Dr. Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, Rt. Hon. Alok Sharma MP, H.E. Sameh Shoukry; moderated by Frederick Kempe

This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Fred Kempe: The success of future COPs relies on sustaining the momentum of those past and identifying pathways forward for the social, environmental, economic well-being of the global community. Think of it as a sort of relay race for the future, and we have three individuals here, very important individuals, passing the baton to each other. I would like to ask each of you to give a brief review of COP26. What did it accomplish? Where did it fall short?

Rt. Hon. Alok Sharma: We set out very early on in our presidency what we wanted to achieve at COP26. Our overarching ambition was to ensure that we kept 1.5 [degrees] alive and what that means is that the Paris Agreement said that world leaders should work together to limit global temperature rises to two degrees and—aiming for well below that—1.5. And that’s why keeping 1.5 alive was so important for us. The way to deliver that was to get much more progress on emission reduction commitments, on finance to support developing nations, on getting support for adaptation and then, of course, to close off the outstanding elements of the Paris rulebook so that that could be operationalized.

If you look at before Paris, the world was heading towards four degrees of global warming by the end of the century. After commitments at Paris, it was at around three degrees. And now, if you take the commitments made in the lead up to COP26, we are heading to below two degrees. So we kept 1.5 alive.

I would just say that we live in a fractured world in terms of politics. And yet, we had almost 200 countries coming together and ensuring that we were tackling this global problem together. So, I think we can be very proud of what we achieved in terms of the Glasgow climate pact.

When we took on this role, less than 30 percent of the global economy had a net-zero commitment. We now have 90 percent. We’ve got a commitment for countries to phase down coal use. For the first ever, in any of these COP processes, we’ve ensured that the $100 billion funding will be delivered by 2023 to developing countries, maybe earlier and, indeed, developed countries agree to double the amount of adaptation finance support to those countries. And we’ve got various work programs in place as well on driving action on adaptation, on loss and damage.

What we achieved is historic. But I also said in Glasgow that this is a fragile win. And that’s because we now need to spend the coming years ensuring that all these commitments are translated into action. And that, frankly, is what the world demands, and that’s what the populations demand.

H.E. Sameh Shoukry: Let me start by congratulating Minister Sharma of the United Kingdom on the success of COP26, both in terms of the substance and what was achieved. And I believe it was important that COP26 was held after a hiatus of about two years due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of engagement at the multilateral level on climate negotiations. There was a particular need at this juncture to finalize the very last outstanding elements of the Paris Agreement work program, and we hope that COP27 will be equally successful, both from a logistical and a substantive perspective.

I think Glasgow was an important step in the direction we need to be taking on global climate action, that is to say, from pledges to actual implementation on the ground. And I think the main element in COP26 is to finalize the provisions on the markets, transparency, and common timeframes for NDCs. It is important that there shouldn’t be any further delay in implementation. What the world needs today is to focus on implementing commitments outlined in NDCs conclusively and expeditiously on issues of mitigation, adaptation, and providing climate finance to developing countries.

More importantly, outcomes from Glasgow reflected the clear political commitment from all parties to step up climate action on all fronts. The call to submit enhanced NDCs, and to phase out unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies are all steps in the right direction.

In addition, we are also very encouraged by the launch of the comprehensive two-year Glasgow Summit – Sharm el-Sheikh Work Program on the global goal on adaptation, as well as the initiation of deliberations on a new collective qualified role on climate finance.

For all of these reasons, we were satisfied with the COP26. Of course, there are issues pertaining to the developing countries’ ambitions and expectations that we hope will be further developed in the subsequent negotiating process. But we recognize that, in the multilateral negotiating context, we should address—especially in view of the dramatic events of the last two years in terms of climate change—that we need to move in the right direction with the necessary political commitment. And I think that Glasgow provided us the groundwork for future endeavors in this regard.

H.E. Dr. Sultan Al Jaber: It is clear, especially now that the dust has settled, that COP26 was a very good steppingstone. In our view, it was a success. It helped instill the sense of urgency across the board. Glasgow united 90 percent of the world’s economy on the path to net zero and that is a phenomenal achievement. The international community made significant global deals on meeting emissions reductions and forest protection. And of course, we got closer—even if not the whole way—to reaching the $100 billion target for climate financing.

COP26 also succeeded in launching many partnerships and coalitions between governments and the private sector to accelerate progressive innovation, like Aim for Climate, which we in the UAE are proud to be part of. It was launched by the US, and thirty-four other countries have joined us in this very important initiative. And, critically, COP26 finally reached a deal on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. That is a very, very critical success factor because it lays the foundation for effective carbon markets. All of this creates great momentum and a great platform that Egypt and the UAE can, should, and will build on for the progressive approach we are adopting for COP27 and COP28.

Fred Kempe: Egypt’s proposal for the COP27 presidency was “Road to COP27: A United Africa for a Resilient Future.” So, resilience underlines the move toward adaptation. Could you talk about how you look ahead to November 2022 and your biggest priorities in Sharm El-Sheikh?

H.E. Sameh Shoukry: I believe that COP27 will be very important in terms of setting the stage and direction for global climate action in this critical decade. Leading up to 2030, COP27 will be the first step in what we believe should be an implementation decade. The world’s collective effort to implementing NDCs under the Paris Agreement should be stepped up, starting at Sharm El-Sheikh. It will show parties that they should be coming with enhanced ambition in all fronts of the war against climate change, whether in terms of mitigation, adaptation, or climate finance.

COP27 will also build on the outcomes of Glasgow. As the COP-designated presidency, Egypt will focus on achieving progress on the mandates coming from COP26, including the global build-up of adaptation and the new goal of climate finance. This global stocktaking is also an important part of the promises that should be made in in this area, in Sharm El-Sheikh, to allow for assessing where we are and where we need to be implementing the Paris Agreement and achieving its goals.

The impacts of climate change are felt universally all around the world, and those affected most are ordinary men, women and children, and their voices should be heard. We will provide the opportunity for all the stakeholders to be heard loud and clear and to have the necessary impact on the decision makers. It’s important, since their livelihoods are at stake, their wellbeing, and that of their children will be affected.

We believe in strengthening the role of youth and civil society, and we are glad that the first Climate Youth Forum will be convened in Egypt this year. We commit to continuing to engage with the young people around the world, and we believe that this is again an aspect that future COPs should concentrate on.

Fred Kempe: Dr. Sultan, congratulations as well to you on the UAE having the COP28 presidency. You were the first country in the Middle East and North Africa to sign the Paris Agreement, and the first to make a commitment to net-zero by 2050. With this momentum, what will your approach be to COP28?

H.E. Dr. Sultan Al Jaber: Let me respond to your question first by saying that we take on this role with a great sense of responsibility. And as such, I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Asia-Pacific Group of Nations and the UNFCCC Secretariat for the trust they have placed in us.

COP28 is going to be a crucial COP. It will mark the first ever global stocktaking that will show us how we are tracking towards the Paris goals, whether it’s on mitigation, adaptation and, of course, on finance. Critically, it would also set the roadmap towards 2030 and beyond. The work towards a successful stocktaking starts now, and I can comfortably tell you that we have already started working very closely with our colleagues and friends in the UK and in Egypt to make sure that all countries continue the momentum of COP26, especially in aligning the international community around net zero by 2050.

But there is also another dimension that we want COP28 to be defined by, and that goes beyond policy objectives to practical outcomes. We want Abu Dhabi to be where countries turn pledges into concrete results. So, we want this to be the start point that will translate policies, strategies, and plans into real action that will deliver tangible results. Of course, we also want to help take commercially viable climate solutions to scale around the world, especially where they are really needed. This is why we want COP28 to build on the momentum and the excitement created at COP26. We want to build on the progress and the momentum that will be achieved and clearly demonstrated through COP27.

And we want COP28 to be as inclusive as possible, reflecting the views of developed nations alongside developing countries, and also reflecting public and private sectors, scientists and civil society. By inclusive, I mean the expertise that is required to help us prepare for this very important transition. In the energy space, the hydrocarbon industry will have to be included as part of the mix because if we want to successfully transition to the energy system of tomorrow, we can’t simply unplug from the energy system of today, and we can’t do this with a flip of a switch. So, we need to take time. We need to consult and engage all those relevant. We need to include the energy experts in the discussions early to make the current system work more efficiently with much less carbon. We should, of course, leverage expertise from across the energy sector to help find meaningful, practical climate solutions that we all need. We should always remember that our goal is to hold back emissions, not to hold back progress or economic development.

Fred Kempe: Dr. Sultan, what a wonderful comment on holding back emissions but not holding back progress. Mr. Sharma, how do you see the UK working with Egypt and the UAE to capitalize on the fact that the next two COPs are in the Middle East and North African region?

Rt. Hon. Alok Sharma: We are working very closely with our friends in Egypt and the UAE, and I think it’s been a very constructive dialogue with both countries leading up to COP26. My first international travel after COP26 this year of course is Egypt and the UAE, and I hope that demonstrates the fact that we want this partnership to work really well. I’ve been so encouraged by what Mr. Shoukry and Dr. Al Jaber have said about their ambitions for COP27 and COP28. And there’s no doubt that what they are looking to achieve is far more ambitious for COP27 and COP28. And honestly, that’s what we had going into Glasgow with the real ambition for COP26.

And if I may just reflect on one of the key elements that my colleagues and friends have talked about is the power of the private sector. If we want to be on the pathway to limit global temperature rises to well below two degrees—aiming for 1.5–we need to halve global emissions by 2030 relative to what they were in 2010, and to be able to do this we need to get the private sector on board.

And I have to tell you, over the past couple of years and at COP26, we saw the private sector stepping forward. We now have a hundred and thirty trillion dollars of assets from the private sector committed to getting to net zero by 2050. I think this is a really exciting part of what came out of COP26, and I’m sure this will be taken forward at COP27 and COP28 as well.

Dr. Al Jaber, as you talked about, the thing that we wanted to do is to get emissions down. And one of the really important achievements of COP26 was an agreement to have this ratchet, whereby every country’s ministries agree to look at the 2030 emission reduction targets and see whether those would be revised by the end of 2022 so they align with the Paris temperature goals. I think this is an area where we need to work closely together, and I’m really excited about this partnership that we have with two very close friends. And I have no doubt based on what I’ve heard from both of my friends, that they are absolutely committed to having real success at COP27 and COP28. And ultimately, the aim of that, of course, is to deliver a cleaner world, a more prosperous world, and a world that is focused on green growth.

Fred Kempe: Obviously, this is a very special dynamic that we’re going to have the next two COPs in the Middle East and in Africa. How do you feel the region can take advantage of this? And where do you feel most optimistic and where do you see the greatest areas in need of work?

H.E. Sameh Shoukry: Our region continues to be highly affected by the negative impacts of climate change, and Egypt belongs to two regions that are most affected: Africa and the Mediterranean. And as COP President on behalf of Africa, we believe it is our responsibility during COP27 to highlight the priorities of the continent, which has suffered the most and which has contributed the least to the problem that we are facing. In this context, we believe that hosting the COP in Africa hosting represents an opportunity to frame the impacts of climate change and to promote and support the exemplary efforts that African countries have taken to address climate change and to adapt to the impacts in accordance with the Paris Agreement, despite the strains that climate action put on their limited resources.

We can also see that there’s a silver lining in addressing climate change in the Middle East and Africa, expediting the green transformation to the benefit of our economies. We believe there’s a great potential to take advantage of the resources that are available to provide green jobs and to provide opportunities to generate the development ambitions of the African and the MENA regions. We hope that this process will continue to address the vulnerabilities that exist and the necessity to provide resources for the countries most affected.

H.E. Dr. Sultan Al Jaber: The focus on our region in the next three years is an important factor that we should capitalize on. This region has specific advantages that can help accelerate the energy transition.

Firstly, as long as the world continues to rely on oil and gas, we can play a very critical role in helping ensure reliable supplies of the least carbon-intensive oil and gas, and we can make sure that this is available to the market where it’s needed. We are, of course, leveraging this position to drive down carbon intensity through the expansion of many, many initiatives and projects such as carbon capture and storage. We’re also investing in our capabilities in hydrogen, green and blue.

Egypt has been very successful in developing a comprehensive holistic energy strategy, and they are one of the countries that have access to high solar irradiance as well as high wind speeds. And they have been harnessing both solar and wind and playing a very important role in helping advance the renewable energy agenda in an effort to help mitigate climate change and reduce carbon emissions.

In the UAE, we have been investing in solar and wind, and we’ve been investing in the clean technology space for more than fifteen years. We have invested in more than forty countries. We today already have access to twenty-three gigawatts of clean zero carbon emission sources of power in forty countries. That positions us uniquely on the global renewable energy map. And only recently, three of the UAE’s energy giants joined in a strategic partnership to turn Masdar into a clean energy powerhouse. Now, this new supercharged Masdar is going to double its capacity to reach at least fifty gigawatts by 2030. This represents a very unique opportunity for Masdar and for its partners, as well as the region.

So, the energy transition has been embraced by this region and, in particular, in Egypt and in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and of course, in the United Arab Emirates. We’re very serious in advancing this agenda. We see a unique economic development opportunity that is sustainable for the future. If we were to capitalize on our deep expertise, as well as the financial resources we have and the technology access—as well as the partnerships that we’ve been able to create over the years—and again globally, there would be at least three trillion dollars that will be invested in the renewable energy space over the next ten years. We in the UAE see this as a unique opportunity for us to capitalize on and seize with our partners. In fact, this is the thinking behind our net-zero strategic initiative. We see it as a new economic development opportunity that will help us create new industries, new skills, new jobs, new partnerships, and new models of engagement with relevant parties around the world. For us, the business of tackling climate change is simply a good business opportunity and, as such, we are aggressively approaching it.

H.E. Dr. Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber is the Minister of Industry and Advanced Technology; UAE Special Envoy for Climate Change; Managing Director and Group CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC); and Chairman, Masdar, United Arab Emirates. The Rt. Hon. Alok Sharma MP is COP26 President, United Kingdom. H.E. Sameh Shoukry is the Minister of Foreign Affairs, President Designate COP27, Egypt. ADNOC is a sponsor of the 2022 Atlantic Council Global Energy Forum.

COP26 did not deliver everything we wanted, but here is where key progress was made

By Fatih Birol

Climate change is perhaps the greatest challenge that humankind has faced and it is natural—and healthy—that our citizens demand strong action. Therefore, I understand the disappointment and frustration that some people expressed after November’s COP26 Climate Change Conference in Glasgow.

At the IEA, we did not rush into hasty judgments. After taking time to make a considered assessment, I would now say that COP26 actually achieved a lot. Even if it fell short of what we might have ideally hoped for, Glasgow delivered much more than many people perhaps realize.

There are three main areas where COP26 generated important momentum towards helping the global energy sector to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century.

Stronger ambitions

First are the important commitments we saw at the summit and in the weeks leading up to it. Countries that account for about 90% of the global economy have now committed to reduce their emissions to net zero. Of course, pledging to do something and actually doing it are not the same thing, and effective implementation of clear policies to back up these commitments is critical. But governments across the world are now clearly signalling to investors and companies that net zero is where we need to go.

More broadly, IEA analysis shows that if all the energy and climate pledges made by governments ahead of and during COP26 are met on time and in full, it would keep the rise in global temperatures to 1.8°C, the first time this projection has been below 2°C.3 We still have to do everything we can to limit global warming to 1.5 °C, but we still saw a significant step forward in terms of ambition at COP26.

Greater cooperation

We will not successfully reduce global emissions to net zero without strong international collaboration, and that is the second encouraging sign we saw in Glasgow. Two particularly important examples stood out for me. The US-China Joint Declaration was a major statement about the intention of the world’s two largest emitters to work together to accelerate their climate actions, which sends a strong leadership message to the world. And the Just Energy Transition Partnership with South Africa saw a number of countries and institutions coming together to support South Africa’s move away from coal in a way that also focuses on the social aspects of the clean energy transition. On a multilateral basis, the signing of the Global Methane Pledge by over one hundred countries was a major achievement that can make a vital difference to near-term global warming.4

Agreeing on the rules

A third area where I would like to note progress is on rules. A major task in Glasgow was to agree on how to implement different aspects of the Paris Agreement,

and COP26 clearly moved things forward on the inter national rulebook for carbon markets and other key elements. We also saw new mechanisms put in place to encourage countries to keep ratcheting up their commitments at future COPs, which can help close the gap between current commitments and what’s needed to bring us in line with a 1.5°C pathway.

I would like to be able to mention a fourth area, finance, but sadly the progress we saw on that front was not satisfactory. There is still a lot of work to do both in terms of mobilizing the amount of financing that is needed and in channelling it where it can make a real difference, notably in developing economies.

What comes next

As we look beyond COP26, we need to focus on implementation. We need clear and credible policies, major investments, and more clean energy projects and products rolled out around the world to replace the old polluting and emitting infrastructure in use today.

In this vein, I would like to highlight four new initiatives that we at the IEA are undertaking to support rapid and orderly clean energy transitions. Coal accounts for more emissions globally than any other single source and a major new IEA report in June will analyze in detail practical steps between now and 2030 to bring down emissions and air pollution from coal in line with our net zero pathway, while ensuring the transition is fair and affordable, especially for developing economies.

As the IEA’s Roadmap to Net Zero by 2050 shows, we are going to need to generate a lot more electricity on a path to net zero, and it will need to come from a range of low-carbon sources to ensure that supplies are reliable and affordable.5 I was encouraged at COP26 to see nuclear power returning to the fore in this conversation, and our new special report on Nuclear Energy and Net Zero in May will analyse this issue in depth, with a particular focus on the potential role of small modular reactors.

As I mentioned above, the signing of the Global Methane Pledge was a major step forward at COP26. To support the implementation of this pledge, we will be launching an expanded version of our Methane Tracker in February to include estimated emissions from coal, agriculture, and waste.6 And on the subject of tracking, the United Kingdom’s COP26 Presidency asked the IEA to lead global efforts to monitor progress on the Glasgow Breakthroughs, which are aimed at driving down the costs of key clean energy technologies. For this, we will track global progress in critical areas—such as power, road transport, steel and hydrogen—to determine whether it is in line with international climate goals.

In short, COP26 produced valuable progress that can help move the world towards a cleaner and more secure energy future, which is critical to addressing the threat of climate change. The key is for governments not to leave COP26’s gains as mere words, but to put them into action.

3 Fatih Birol, “COP26 climate pledges could help limit global warming to 1.8°C, but implementing them will be the key,” IEA Commentaries, November 4, 2021, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/cop26-climate-pledges-could-help-limit-global-warming-to-1-8-c-but-implementing-them-will-be-the-key.

4 “Executive Director joins world leaders for launch of Global Methane Pledge,” IEA, November 2, 2021, https://www.iea.org/news/executive-director-joins-world-leaders-for-launch-of-global-methane-pledge.

5 International Energy Agency, Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, May 2021, https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050.

6 International Energy Agency, Methane Tracker Database, October 7, 2021, https://www.iea.org/articles/methane-tracker-database.

Fatih Birol is the Executive Director of the International Energy Agency.

COP26 and the Climate Action Solution Centre

By Rt. Hon. Charles Hendry

As the owners of the Blair Estate, a castle just outside Glasgow, my wife and I were honored and delighted to host the Climate Action Solution Centre (CASC), an exceptional array of events on the sidelines of COP26 organized by a consortium including the Atlantic Council, Liebreich Associates, National Grid, and Octopus Energy. As global leaders from the public sector, industry, and civil society met in Glasgow to negotiate the Glasgow Climate Pact and make public commitments to decarbonization, we hosted some of the most influential decisionmakers for a series of private conversations intended to identify solutions to the thorniest climate challenges.

In a way, Blair Estate is symbolic of the approach that was needed to make the COP discussions successful. The house has evolved over 900 years with countless generations making individual decisions, which have led in time to the creation of the magnificent mansion and surrounding estate you see today.

It is that same spirit that was needed at COP, but on a much bigger scale, with global leaders coming together to make decisions which would be seen many years in the future as providing a turning point in the fight against climate change.

The house has never been so alive, with more than 1600 people coming through the doors over the twelve days of COP26. CASC brought together people from across the world to talk about what we need to do; who needs to do it; and how the whole process can be accelerated to meet the challenge.

And it was that concept of “solutions” that was at the heart of every discussion. There was an extraordinary buzz of positivity, of people saying that they know what needs to be done and how it can be achieved. The feedback after every discussion was that people felt more positive about what could be done rather than overwhelmed by the scale of the challenge.

The discussions—from early morning to late at night—looked at the same issues being addressed by the global leaders at COP26 itself on how we decarbonize our societies and our activities, such as energy efficiency, finance, hydrogen, aviation, methane reduction, critical minerals, and the future of fossil fuels.

The conclusions recognized that past COPs have failed to assign energy efficiency its rightful importance. Governments and capital markets all need to deliver more on energy efficiency to make sure we optimize the resources we use. In this regard, regulation will be necessary, and we need to address the issue of how to do this in a way that delivers a just transition and environmental justice.

It was absolutely clear that the financial community is now moving ahead of governments, recognizing the huge opportunities in the green economy. That will mean we will need to have better ways of comparing the actions of companies so investors and advisers can make effective comparisons. No one suggested that adequate funding was a barrier to delivering net-zero emissions by 2050; on the contrary, with $130 trillion reputedly available, the question is how to use that finance most effectively.

There was genuine debate around the role for hydrogen—its viability and the scope for green hydrogen at an affordable cost to replace gas—especially for industrial purposes. That debate mirrors the discussions in government and industry, but even if the solutions are not yet clear, it is an issue which is being discussed with a seriousness and commitment that was simply not evident just a few years ago.

The continuing role of fossil fuels was at the heart of many discussions; we grappled with ways to balance the need to move at much greater speed towards low-carbon solutions whilst ensuring that such ambitions remain deliverable. If anything, we would have welcomed more participation by the industry in the discussions in and around COP, as it will play a central role in determining the speed of change and how traditional sectors can become green.

It was recognized that the supply of critical minerals will determine the pace of progress. An estimated three billion metric tons of critical minerals will be needed to achieve the Paris Agreement goals by 2050, but at present the broader ESG issues are unclear, with insufficient focus on the environmental and working practices of procuring and processing the requisite minerals at scale.

There was, rightly, discussion about tackling methane emissions and especially how the Global Methane Pledge can be extended to include current non-signatories. The immediate requirement is more accurate monitoring and verification, so that any carbon border tax or adjustment policies can be effective.

We looked, too, at how nature-based solutions can be encouraged, and how the accounting mechanisms might be made less challenging. Again, measurement will be key to success.

For aviation, the focus was on how the provision of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) can be massively developed and then combined with the need for the right policy signals from government to drive investment decisions.

For us, as the owners of Blair, it was exactly what we had wanted to achieve with the house. We wanted to show that one of Scotland’s most historic houses could be at the heart of finding solutions to the challenges of the 21st century. Judging by the level of enthusiasm and the desire of so many people to repeat the exercise and maintain the momentum, we hope that goal was shared by our guests as well.

The Rt. Hon. Charles Hendry CBE PC is a professor at the University of Edinburgh and is a former United Kingdom Minister of State for Energy at the Department for Energy and Climate Change. Charles and Sallie Hendry are the owners of the Blair Estate.

Resource efficiency is crucial for sustainable development

By Jonathan Maxwell

Efficiency first

Energy efficiency is one of the most important priorities for the global energy economy and policymakers in the coming decade. It should be at the very top of the agenda for all businesses and governments. The United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow called for energy efficiency improvements, alongside increases in clean power generation, as one of the last features included in the Glasgow Climate Pact and topics of the conference. This is most welcome, but in the future, it should be the first item on the agenda.

Everyone and everything depends on energy; modern society simply does not function or communicate without it. Energy sources are worth trillions of dollars and are one of the most valuable commodities in the world. It is at the heart of both the problems with and the solutions to climate change, involving at least half of global greenhouse gas emissions. Yet we waste most of it.

We must now re-focus urgently on energy efficiency for three key reasons. The first is security. The second is cost. The third, and potentially most universal in the long term, is carbon.

Security

Grids fail. Superstorm Sandy hit New York in 2012 with such a devastating effect, both economically and in terms of loss of life, partly because New York lost power. Fast forward to February of 2021, when the grid failed in Texas as a result of three severe storms, stranding communities and businesses and bankrupting energy companies. The problem hit Louisiana in the summer, and volatile supply is hurting California now. These failures were often related to climate, weather, or natural disasters. But geopolitical risks are just as serious, with scant natural gas supplies disrupting markets in Europe at the time of writing. Grid decentralization and energy efficiency can help address these problems. Conservation and on-site energy generation using local and renewable resources can deliver more reliable solutions that depend less, if at all, on the grid. Policymakers in Europe and the United States have now started to budget and legislate accordingly. China already uses energy efficiency policy to decouple energy demand from economic growth.

Cost

Utility energy prices are a function of the cost of generation, but also of the cost of maintaining centralized transmission and distribution through the grid, as well as tax and market incentives. These costs are too high because we waste two-thirds to three-quarters of energy before it gets to the point of use, through generation, transmission, and distribution losses associated with a centralized grid. These losses occur because energy is often sourced far from where it is used and where there is no use for heat that is produced along with the power, resulting in waste. Indeed, according to the World Economic Forum, some 70 percent of original energy is wasted in the United States, while more than two-thirds of original energy is wasted in Europe. Meanwhile, 70 percent of all energy is used in buildings, industry, and transport, not all of which are efficient. At least 20-30 percent is wasted through sub-optimal equipment such as lighting, motors, controls, heating ventilation, and air conditioning. Decentralization through on-site generation can slash losses on the supply side, while better and more efficient equipment can reduce waste on the demand side. Cutting energy waste reduces costs and improves productivity and profitability.

Carbon

The clock is ticking, and the science is clear. We have a very limited global carbon budget that we will have spent by the end of this decade, and we have no more than this next generation—i.e., the next twenty to thirty years—to decarbonize while transforming the way that we generate and use energy and other resources. The International Energy Agency states that energy efficiency represents at least 40 percent of the decarbonization needed in the energy sector by 2040.

Most companies and governments are committed to limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C and to net-zero carbon by 2050. But there is simply no such thing as zero-carbon energy generation. Creating new renewable energy generation infrastructure emits carbon, and there are limits to its penetration over time. Today, 80 percent of the world’s energy system is still based on oil, natural gas, and coal, with massive associated investment in infrastructure and supply chains that will take time as well as money to decarbonize. Global energy demand is projected to rise nearly 50 percent by 2050. During this time, there is expected to be more growth in emissions from demand for cooling, which is set to triple, than there is from the entire energy demand from China and India combined today. Decarbonization is going to be a massive long-term investment and we should use energy efficiency to deliver and fund as much of it as possible.

We have to focus on reducing demand for energy and promoting the most efficient ways of generating, transmitting, distributing, and using energy with the best available technology. On-site generation and more efficient equipment in buildings in industry is a large part of the solution. So too is electrification of transport. ‘Well-to-wheel’ efficiency based on oil is some 15-30 percent compared to 75 percent plus from ‘wind-to-wheel’ electricity, and that is before we consider the pollution prevention benefits. Indeed, more people die from premature lung disease in cities than from road traffic accidents, and from war, terrorism, and murder combined. Energy efficiency does not rely on technologies that are yet to be invented, and it can be delivered now, often at lower cost and more reliably than business as usual. The cheapest and cleanest energy is the energy that we don’t use or waste. It is what the International Energy Agency calls the “First Fuel.” Energy efficiency provides the biggest ‘bang for the buck’ from a greenhouse gas emission reduction perspective and it should come first.

From energy transition to energy transformation

In the last decade we saw the market for energy efficient lighting grow from less than 2 percent penetration to over 60 percent globally. Today, electric vehicles are a mere 2 percent of US auto sales. There is a vacuum to fill. There will be a billion new air conditioners in the next five to ten years, and the fluorinated refrigerant gases associated with the old ones are thousands of times more potent than CO2. Methane, unless captured from oil and gas production and landfill sites, is eighty times more potent than CO2 over twenty years. The market for more energy efficient solutions is worth trillions of dollars, potentially two to three times the size of the renewable power market that is rightly attracting US$1-2 trillion per annum in new capital investment. The time to transform the way that we supply and use our energy has come, and we must do so urgently. This revolution involves doing more with less. It is highly profitable. The rewards could not be larger.

Resource efficiency is synonymous with sustainable development. It must come first.

Jonathan Maxwell is the CEO and Founder of Sustainable Development Capital LLP, which was a co-sponsor of the Climate Action Solution Centre.

Nuclear energy is essential to achieving a clean, affordable, and equitable energy system for the future

By Sama Bilbao y León

Nuclear energy offers a golden opportunity to build a cleaner, more equitable world, in which everyone has access to low-carbon, affordable, abundant energy and a high quality of life.

This opportunity comes at a time of need for urgent and realistic action on climate change. Throughout 2021—and at the COP26 conference in Glasgow—there was a clear recognition of the severity of impacts from climate change and a greater commitment from the international community to implement pragmatic approaches to achieving net-zero carbon emissions.

While achieving net-zero emissions by the middle of this century is critical to limiting climate change to 1.5 degrees Celsius, this alone is simply not enough. We must also ensure that the clean energy systems of the future are equally available to everyone in the world and that everyone has access to the around-the-clock reliable energy that powers quality of life in high-income countries.

Meeting this urgent and massive challenge requires an ambitious, pragmatic, and multi-pronged approach. No single energy technology can achieve this on its own.

Nuclear energy is currently the world’s second largest source of low-carbon electricity, meeting more than 10 percent of global electricity demand and accounting for more than 30 percent of global low-carbon electricity.7 Nuclear generation has provided reliable, clean electricity for decades, avoiding the emissions of more than 70 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide over the last fifty years.

We must use, as efficiently as possible, the low-carbon energy that we currently have, and put in place an aggressive action plan to deploy as much new clean generation as fast as is feasible at a global level. Maximizing the contribution of existing nuclear power plants is, according to the IEA, the most cost-effective low-carbon energy investment available today.8 Not only we can ill afford to lose such a significant source of emissions-free electricity, but existing nuclear power plants will be instrumental to help bridge the gap as we accelerate the deployment of new low carbon generation. With more than 75 percent of the global nuclear fleet under 40 years old, and the first approvals for 80 years of operation having been passed in the United States, there is every opportunity for these reactors to continue to produce low-carbon electricity well beyond 2050.

But if we are going to keep the 1.5-degree target within reach in a cost-effective and socially equitable manner, we will need much more energy, and we will need it urgently. The great news is that nuclear energy is one of the only technologies that can produce low-carbon electricity and heat, which could be a game-changer to decarbonize other hard-to-abate sectors beyond electricity, such as industrial processes, heating and cooling of buildings, and hydrogen generation.

According to the World Nuclear Association’s Harmony vision, to meet global decarbonization and sustainable development needs, nuclear energy will need to play a significant role, with more than 25 percent of global electricity generated by nuclear energy by 2050, along with a significant proportion of non-electric applications.9 This means adding about 30 GWe of nuclear power generation every year, which is ambitious but on par with the nuclear construction rates of 31 GWe per year achieved in the mid-1980s.

World Nuclear Association data show that there are currently over one hundred reactor units planned and a further 325 units proposed by governments around the world.10 Since COP26, we have seen a number of new proposals and policy announcements, indicating a growing recognition of the crucial role nuclear energy must play in the future. France announced that it would build new nuclear power reactors to maintain its energy security and to meet its climate change goals. US and Romanian companies announced a partnership to build a first-of-a-kind small modular reactor in Romania. The UK announced regulations to introduce a new funding model to attract a wider range of private investment for new nuclear power projects, as well as funding support for the development of domestic small modular reactor technology. The Netherlands announced plans to build two nuclear power stations in a bid to hit more ambitious climate goals. Poland continues aggressive plans to replace existing coal generation with nuclear plants, large and small. China reiterated plans to build 150 new nuclear units by 2050, while India announced a goal of more than 22 GW of nuclear capacity by 2031. Russia has a number of active nuclear projects both inside the country and abroad, such as in Bangladesh, Egypt, and Turkey.

In the year leading up to COP26, much has been achieved: in 2021, over 5 GWe of new nuclear capacity was connected to grids across the world, in China, India, Pakistan, and the UAE. Construction also began on an additional 6 GWe. Unfortunately, this is not close to the 30 GWe needed, making it crucial for governments to implement clear policy actions to accelerate the deployment of new nuclear.

We must establish human, physical, commercial, and institutional infrastructure that will allow the global nuclear sector to scale up fast to meet the need for urgent and massive decarbonization. A lot of the work should take place within the nuclear industry itself, making the most of lessons learned from recent first-of-a-kind projects and capitalizing on rebuilt capabilities and expertise. But government support will be indispensable: policies and market frameworks that establish a level playing field for all low-carbon technologies—and that instill confidence and a long-term vision for energy strategies—will be instrumental to incentivize investment in nuclear energy projects and associated supply chains, as well as to streamline licensing and regulatory systems.