So, this is what life feels like “in the foothills of a new Cold War,” as Henry Kissinger has called it. Though perhaps the better metaphor would be “in the trenches,” for this week one could hear the steady din overhead from the escalating U.S.-Chinese conflict that will define our times.

On Monday, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo blasted China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea as “completely unlawful,” and he pledged U.S. support for those countries that would wish to challenge Beijing.

For its part, China sanctioned Senators Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, among others, in retaliation for their legislative actions against Chinese officials linked to the detention and repression of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang.

On Tuesday, President Trump signed into law a bill to impose new sanctions on Chinese individuals, banks and businesses that are helping Beijing’s Hong Kong crackdown. On the same day, Prime Minister Boris Johnson made his UK the first European country to ban use of Huawei’s 5G equipment.

Meanwhile, China threatened to sanction Lockheed over its defense sales to Taiwan, a warning shot to defense companies across the world. Beijing military and political officials increasingly share with foreign counterparts their ambition to alter Taiwan’s independent status by the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party in July of next year.

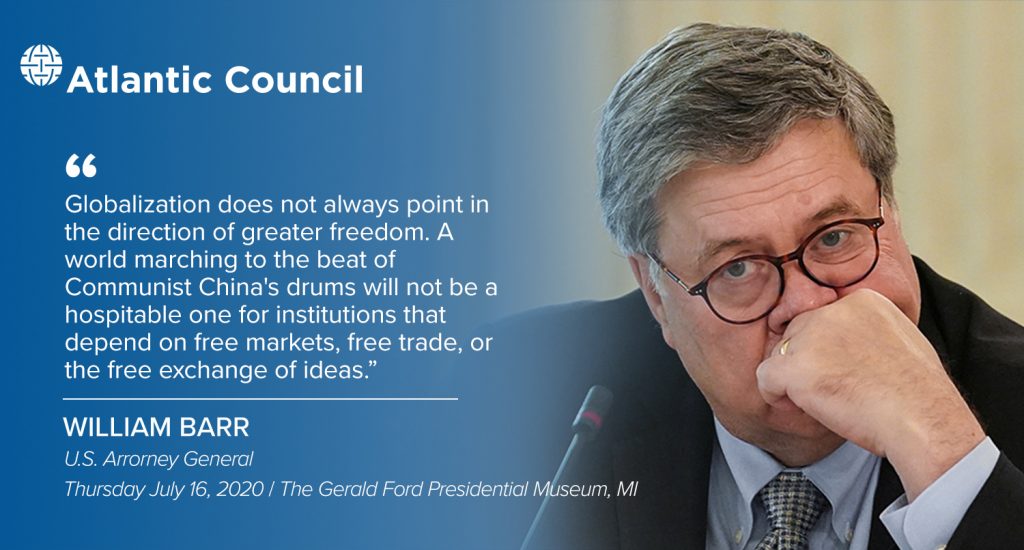

This Thursday, U.S. Attorney General William Barr branded some U.S. entertainment and tech companies – Disney, Google, Microsoft, Yahoo and Apple among them – as “all too willing to collaborate” with the Chinese Communist Party. That followed last week’s charge by FBI director Chris Wray that Beijing pursues its ambitions through industrial espionage, theft, extortion, cyberattacks and malign influence activities.

All this comes in the face of an unprecedented Chinese global propaganda, economic and intelligence blitz to seize the myriad opportunities that present themselves to China as the first major economy to recover from the pandemic it unleashed. China this week announced 3.2% growth in its second quarter, after a 6.8% decline in the first quarter, even as the United States and Europe remain in recession.

Under the cover of the coronavirus fog, China has stepped up its repression of its ethnic Muslim minorities, tightened its grip over Hong Kong, increased its pressure on Taiwan, stepped up tensions in the South China Sea, escalated attacks on Australia for seeking a coronavirus investigation, heightened pressure on Canada for detaining a Huawei executive, unleashed fatal force on the border of India and ratcheted up its propaganda against the United States.

Get the Inflection Points newsletter

Subscribe to Frederick Kempe’s weekly Inflection Points column, which focuses on the global challenges facing the United States and how to best address them.

“China may simply be taking advantage of the chaos of the pandemic and the global power vacuum left by a no-show U.S. administration,” write Kurt M. Campbell and Mira Rapp-Hooper this week in Foreign Affairs. “But there is reason to believe that a deeper and more lasting shift is underway. The world may be getting a first sense of what a truly assertive Chinese foreign policy looks like.”

Some argue that the danger of a U.S.-China war is growing. What that misses, a prominent Asian business leader told me this week, is that China has already decided the war has begun. Like the Cold War before it, the outcome is unlikely to be decided by military means. Also like the contest before it, the war will be fought not over days but over decades.

The conventional wisdom is that China is a far more formidable peer competitor than the Soviet Union ever was, given its size, economic might and technological prowess. The Chinese economy that accounted for less than 2% of global GDP in 1980 is now at some 20% of global GDP.

The conventional wisdom follows that the United States is far less equipped in Cold War II to take on this competitor than it was during Cold War I, with its alliances weakened, its domestic politics polarized, its national debt spiraling and its COVID-19 health and economic misery growing worse.

That said, many of the lessons of the last Cold War can be applied to this one. With military deterrence, strategic patience and a renewed effort to galvanize Asian and European allies, the fundamental strengths of democracies and weaknesses of autocracies still would be decisive.

Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, one of the world’s leading experts on China, has called for a “managed strategic competition.” Each side would understand and accept the other’s red lines and core interests, difficult areas for cooperation could be identified (such as trade), and cooperation in easier areas could be advanced (such as for pandemics and climate change).

And though it may appear that China is ascendant, its system has grown more vulnerable as it has become more authoritarian under President Xi.

China’s weak spot

Chinese-American political scientist Minxin Pei notes that during the five decades of Cold War “the rigidity of the Soviet regime and its leaders proved to be the United States’ most valuable asset.”

He argues that Chinese rigidities have been increased by President Xi’s decision in 2018 to abolish presidential term limits, his heavy-handed purges of prominent party officials, his suppression of Hong Kong, the tightest media censorship since Mao, the incarceration of more than 1 million members of Muslim minorities, and over-centralization of economic and political decision-making.

“The centralization of power under Xi has created new fragilities and has exposed the party to greater risks,” writes Pei. “If the upside of strongman rule is the ability to make difficult decisions quickly, the downside is that it greatly raises the odds of making costly blunders.”

Trump administration officials believe their increasing efforts to counter a more assertive China could prove to be their most significant foreign policy legacy. That will only be true if they can combine it with a strategy that can sustain the effort in concert with allies and far beyond the limits of any single U.S. administration.

This article originally appeared on CNBC.com

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe.

THIS WEEK’S TOP READS

The top reads in this week’s special edition include two looks – one from Kurt Campbell and Mira Rapp-Hooper in Foreign Affairs and the other from Larry Diamond in The American Interest – at why Chinese international policy has shifted to a more aggressive and impatient posture and what response that requires of the United States and its allies.

The Financial Times this week published much on Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s seismic shift to ban the use of Huawei equipment in the United Kingdom. Worth including below were Phillip Stephens’ look at the deeper lessons for “global Britain” behind this move and Constanze Stelzenmüller’s thoughtful look at how this should influence “Europe’s fateful choice” on Huawei.

Also, don’t miss this week’s new must reads.

Wall Street Journal reporters Bradley Hope, Justin Scheck and Warren P. Strobel investigate the Saudi manhunt for a former spy chief and what it says about how the country was run then and now.

Writing in The Atlantic, former deputy secretary of state Bill Burns provides required reading for any would-be strategists on why the United States will defend its interests best if it “reinvents” the way it approaches the world rather than being seduced by the either temptations of self-defeating “retrenchment” or unattainable “restoration” of the past decades’ dynamic.

#1. CHINA’S LASTING SHIFT?

China is Done Biding Its Time

Kurt M. Campbell and Mira Rapp-Hooper / FOREIGN AFFAIRS

“It’s too early to tell with certainty,” argue Kurt Campbell and Mira Rapp-Hooper in Foreign Affairs, “but China – imbued with crisis-stoked nationalism, confident in its continued rise, and willing to court far more risk than in the past – may well be in the middle of a foreign policy rethink that will reverberate around the world”

Read this article and you’ll be left disagreeing only with “it’s too early to tell,” as China leverages its first-escaper status from coronavirus to take full global advantage.

“In the months since the pandemic first engulfed the world,” they write, “China’s government has engaged in an unprecedented diplomatic offensive on virtually every foreign policy front. It has tightened its grip over Hong Kong, ratcheted up tensions in the South China Sea, unleashed a diplomatic pressure campaign against Australia, used fatal force in a border dispute with India, and grown more vocal in its criticism of Western liberal democracies.”

Sounds like a lasting shift to me that’s increasingly easy to see. Read More →

#2. “A PERIOD OF GRAVE DANGER”

The End of China’s “Peaceful Rise”

Larry Diamond / THE AMERICAN INTEREST

“Recent developments signal a new authoritarian bravado and belligerence on the part of the PRC,” writes Larry Diamond, one of the world’s leading experts on defending democracy, in The American Interest.

“The three most worrisome aspects of this are the betrayal of Beijing’s commitment to Hong Kong’s autonomy; the escalating pace of PRC militarization and muscle-flexing in the South China Sea; and the growing existential challenge to the freedom and security of Asia’s most liberal democracy, Taiwan.”

Diamond writes that the deteriorating U.S.-China relationship is “entering a period of grave danger… Whether the United States and its allies exhibit the strategy and resolve to meet this threat will be the single most important determinant of world order in the coming decade.” Read More →

#3. NOTHING QUIET ON THE 5G FRONT

Huawei and the hard facts facing global Britain

Philip Stephens / FINANCIAL TIMES

Europe faces a fateful choice on Huawei

Constanze Stelzenmüller / FINANCIAL TIMES

One crucial inflection point this week was Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s move as the first European country to ban the use of Huawei equipment. FT columnist Philip Stephens judges that it was the right move in national security terms but a result move of U.S. “coercion” rather than any clear-sighted assessment of the right course.” Read More →

Also writing in the FT, Constanze Stelzenmüller correctly reckons that the British shift deprives Europeans of cover with “both the U.S. and China breathing down their necks.” She’s right that Beijing is making the U.S. case easier with “its hardening authoritarianism and persecution of minorities at home; its drive for regional hegemony; its aggressive pursuit of physical, economic and digital assets in Europe…” Read More →

#4. A SAUDI SPY STORY

Saudi Arabia Wants Its Fugitive Spymaster Back

Bradley Hope, Justin Scheck and Warren P. Strobel / THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

It’s hard to find reliable, fact-based reporting on anything regarding Saudi Arabia these days. By that measure alone, this front-page story in the weekend Wall Street Journal is worth reading on an international fugitive who once was U.S. intelligence’s favorite Saudi anti-terrorism contact.

“The bitter fight between the Saudi government and (Saad al) Jabri opens the books on the country’s system of patronage, business deals and alleged self-enrichment, all done in the name of fighting terrorism,” write Bradley Hope, Justin Scheck and Warren P. Strobel.

What the piece shows in rich detail is “a multibillion-dollar network that enriched high-ranking Saudi government officials while exerting the kingdom’s influence abroad.” Read closely and you’ll see it might have been corrupt, as officials now charge, but it was also business as usual. Personal enrichment was a built-in and condoned part of the system. Read More →

#5. REINVENTING U.S. FOREIGN POLICY

The United States Needs a New Foreign Policy

William Burns / THE ATLANTIC

One of the finest diplomats of our times, former deputy secretary of state Bill Burns, delivers one of the wisest reflections I’ve read on U.S. global challenges and how to best manage them. It is this week’s must-read for the clarity with which he lays out the alternatives and reaches conclusions that could shape a new era of American leadership.

“The United States must choose from three broad strategic approaches: retrenchment, restoration, and reinvention,” he writes this week in The Atlantic. “Each aspires to deliver on our interests to protect our values: where they differ is in their assessment of American priorities and influence, and of the threats we face.”

Read this piece and you’ll find it impossible to disagree that reinvention is the only plausible alternative when balanced against the defeatism of retrenchment and the impossibility of restoration.

“We live in a new reality: American can no longer dictate events as we sometimes believed we could,” he writes. “We can’t afford to just put more-modest lipstick on an essentially restorationist strategy, or, alternatively, apply a bolder rhetorical gloss to retrenchment. We must reinvent the purpose and practice of American power, finding a balance between our ambition and our limitations.” Read More →

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

ATLANTIC COUNCIL TOP READS

Image: Hand out photo dated July 6, 2020 of Aircraft from Carrier Air Wing 5 and Carrier Air Wing 17 fly in formation over the Nimitz Carrier Strike Force. The aircraft carriers USS Nimitz (CVN 68), right, and USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) are conducting dual carrier operations in the Indo-Pacific as the Nimitz Carrier Strike Force. Two US Navy aircraft carriers have resumed rare dual exercises in the South China Sea, the second time this month the massive warships have teamed up in the contested waters. The USS Ronald and USS Nimitz carrier strikes groups, comprising more than 12,000 US military personnel among the two aircraft carriers and their escorting cruisers and destroyers, were operating in the South China Sea as of Friday July 17, the US Pacific Fleet said in a statement. The presence of the Nimitz and Reagan in the South China Sea earlier this month marked the first time two US aircraft carriers have operated together there since 2014 and only the second time since 2001. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Keenan Daniels via ABACAPRESS.COM