Assessing Saudi Vision 2030: A 2020 review

Executive summary

When global oil prices collapsed in summer 2014, Saudi Arabia confronted one of the most daunting economic challenges of its modern history. Upon ascending to the throne the following year, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud and his son Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud (now the crown prince) responded by developing an ambitious economic and social reform plan, Saudi Vision 2030, which was unveiled in 2016 and designed to reduce the country’s dependence on oil by facilitating the emergence of a robust private sector.

Saudi Arabia initially decided to evaluate with benchmark goals the first four years of its economic transformation in 2020. With unfortunate timing, the coronavirus pandemic and dramatic shock to oil prices (which occurred just as this publication was going to print) hit Saudi Arabia’s economy hard in 2020. The project the Saudi royals took on was never going to be easy, but plummeting oil prices, disruption of global trade and financial markets, a freeze on industries like tourism, and huge lost productivity in the government and private sector spell an uncertain future for the Saudi plan. Even before the pandemic, the government’s detention of wealthy Saudi businessmen at the Ritz-Carlton in Riyadh, the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul, and increasing tensions with Iran had diverted international attention from the economic reform effort and damaged Saudi Arabia’s international reputation.

However, it is perhaps clearer than ever that it remains in the interest of Saudi Arabia and the United States for the economic transformation to succeed. Four years after the Saudi reform program was unveiled, this study seeks to take a comprehensive look at the state of the Vision 2030 effort: What were the objectives of its creators, what has happened so far, to what extent are reforms advancing these initial objectives that the Saudi government set for itself, and what changes need to be enacted for reforms to succeed?1To note, this is not an assessment of Saudi Arabia’s human rights record or political governance. To the extent that this paper does address either of these two issues, it is in the context of how they have affected the economic reform plan. This is an assessment of progress against the Saudi leadership’s own vision for itself and of whether that vision provides for a sustainable economic path, not against any number of aspirations held by individual Saudis or the international community.

Four years after the Saudi reform program was unveiled, this study seeks to take a comprehensive look at the state of the Vision 2030 effort.

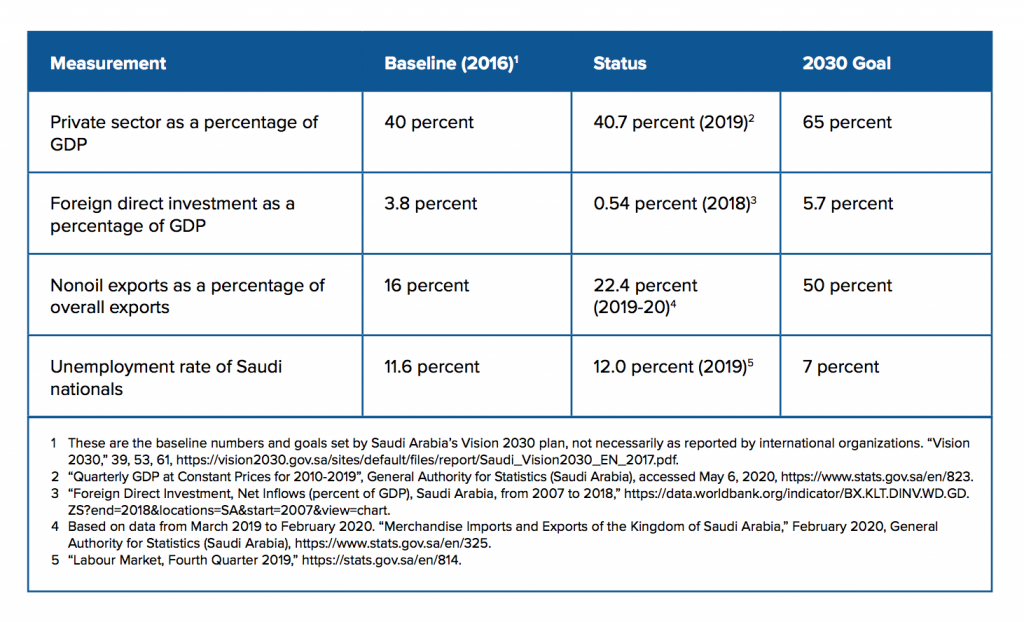

Using Vision 2030’s own “Key Performance Indicators” (KPIs) where available, economic data on Saudi Arabia, and comparative national surveys, the authors attempt to objectively assess the progress and approach toward this reform program to date. What they find is that the Saudi government has invested a tremendous amount of energy, effort, and money in the Vision 2030 reforms, with some noteworthy achievements to date: namely in terms of fiscal stabilization and macroeconomic management, the development of capital markets and the banking system, the digitization of government services, and social reforms. In many other areas, however, reform efforts are falling short of their intended objectives, most notably in creating jobs and transforming the private sector into an engine of growth.

As for the Saudi government’s approach to reform, there is broad recognition that Saudi Arabia must change. However, when the authors spoke to officials in 2018 and 2019, there seemed less of a sense of urgency regarding the pace and a lack of understanding of the depth of the transformation required. The government has concentrated economic and political decision-making at the top and focused its efforts on using institutions like the Public Investment Fund (PIF) to attract foreign investment, so far without great success.

Saudi Arabia now faces another economic crisis, only six years after the 2014 oil price collapse, and it may feel the need to reevaluate some of its Vision 2030 programs.

Saudi Vision 2030 relies on massive government spending and the ability to attract foreign capital, particularly in areas like the PIF-funded megaprojects; both spending and investments are likely to be impacted by the current crisis. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that Saudi Arabia’s economy may contract by 2.3 percent in 2020, and the nonoil GDP may slow by 4 percent. It remains to be seen if Saudi Arabia has the political and fiscal space to both address the crisis at hand and implement an economic reform program amid a potential global recession.2“World Economic Outlook, April 2020: The Great Lockdown,” international Monetary Fund, April 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/ issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020.

If there is good news to be found, it is that Saudi Arabia has already identified the fundamental reforms required for the kingdom’s long-term economic health, and it has begun the work of implementing many of them. The core tenets of Vision 2030 still ring true: the need for job creation, bolstering the private sector, diversifying the economy, and investing in sectors where Saudi Arabia can be globally competitive.

In the study’s final recommendations, the authors urge the Saudi government to abandon the temptation to micromanage economic change from on high and to return to the original spirit of the Vision 2030 reforms, which was to find sectors where Saudi Arabia can compete globally, and to enable the entrepreneurial capacities of its citizens. To achieve these goals, Saudi Arabia should turn away from megaprojects and a completely top-down approach, and make serious commitments to education and human capital development, to ceding space in the economy to the private sector, to continuing improvements in the regulatory environment, and finally to greater transparency and rule of law.

Watch the launch event

Related content

Through our Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative, the Atlantic Council works with allies and partners in Europe and the wider Middle East to protect US interests, build peace and security, and unlock the human potential of the region.