Introduction

Whither the economic fortunes and geopolitical clout of Gazprom and Rosneft? At the height of the commodity boom in 2008, Russian President Vladimir Putin bragged about them as unstoppable global industry leaders. More than a decade later, the heyday of high oil and gas prices is past, and Russia’s two natural resource champions face a comeuppance: international competitors are outpacing them in market valuation, global and regional market access, capital investment, and revenue/cost efficiency. Still, there is no movement for a Gazprom revamp or a Rosneft overhaul. Instead, hard-nosed financial analysis shows their value is not to be found in investor returns. Rather, it is recorded somewhere in Putin’s geopolitical ledger.

Early in his rise to power, Putin enunciated his national champions strategy, declaring that “regardless of who the natural, and in particular mineral, resources belong to, the state has the right to regulate the process of their development and use, acting in the interests of society as a whole…”1Vladimir Putin, “Mineral Raw Materials in the Strategy for Development of the Russian Economy,” Transactions of the Mining Institute (1999).

Other national governments, too, take a hands-on approach to their energy industries but methods and motives make all the difference between success and collapse. Norway represents a best-in-class example. For decades it has benefited from the petroleum sector being a key driver in its economy. As one of the global top petroleum sector exporters, Norway’s oil and gas sector is projected to constitute 10 percent of Norwegian gross domestic product (GDP) and 31 percent of Norwegian exports in 2020.2“Exports of Oil and Gas,” Norsk Petroleum, last updated May 12, 2020, https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/production-and-exports/exports-of-oil-and-gas/. In 2019, Norway ranked third behind Qatar and Russia as the largest natural gas-exporting country.3Photius.com, Natural gas – exports (cu m) 2019 Country Ranks, https://photius.com/rankings/2019/energy/natural_gas_exports_2019_0.html But unlike Russia, which remains a highly corrupt middle-income country, Norway is one of the richest countries in the world with an outstanding social welfare society, minimal corruption, and very equal income distribution.4Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index, 2019, https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi#; The World Bank, World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SI.POV.GINI&country=#

Venezuela represents the opposite extreme, having ended up with the worst economic depression, hyperinflation, and humanitarian crisis in South America’s history in large part due to the misguided destruction of its oil industry, which accounts for more than 90 percent of its exports. In Russia’s case, the specific nature of Russian state “guidance and support” has had mixed results as these companies sacrifice their market values to pursue middling overseas investments or non-core, often commercially suspect projects.

This paper starts out by considering how markets put a value on Gazprom and Rosneft. The business strategies of these companies are evaluated, particularly in light of recent significant changes in global oil and gas market dynamics. Special attention is given to these companies’ peculiar focus on contractors rather than shareholders, including the state, and the primacy of geopolitical objectives in their business model. This is followed by analysis of three regulatory-related setbacks—Western sanctions, the European Union (EU) antitrust case against Gazprom, and Gazprom’s arbitration losses—before reaching the conclusion: these two Russian national champions have functioned less to return value to shareholders, including Russia’s treasury, than to prop up the Kremlin’s domestic and foreign policy objectives and enrich Putin’s circle of cronies.

These two Russian national champions have functioned less to return value to shareholders, including Russia’s treasury, than to prop up the Kremlin’s domestic and foreign policy objectives and enrich Putin’s circle of cronies.”

Gazprom Chief Executive Alexei Miller and Rosneft Chief Executive Igor Sechin react as they wait before a session of the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok, Russia September 7, 2017. REUTERS/Sergei Karpukhin

Production and market value

Gazprom and Rosneft command priority attention from the Russian state due to their enormous size and their great roles in both the domestic and global economies. In 2019, Gazprom produced 68 percent of Russia’s and 11 percent of the world’s natural gas, earning $118.3 billion in revenue and a net profit of $19.6 billion. Rosneft produced 41 percent of Russia’s and 6 percent of the world’s oil, and earned $134.0 billion in revenue for a net profit of $12.4 billion that year.5Gazprom, Gazprom.com; Rosneft, Rosneft.com.

The markets have not exactly rewarded Gazprom and Rosneft for their recent financial performances. As of April 17, 2020, Gazprom’s market capitalization stood at $58.8 billion, an 84 percent slump from its 2008 peak of $367 billion.6Market capitalization values, dividend yield, and P/E trailing twelve months (ttm) statistics from https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/ April 17, 2020. Rosneft’s market capitalization stood at $43.7 billion, half of its $80 billion value when it went public in 2006.7Market capitalization values, dividend yield, and P/E trailing twelve months (ttm) statistics from https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/ April 17, 2020. It was a far cry from Putin’s confident prediction in 2008, with Gazprom at the top of the market, that the company would soon be worth $1 trillion. It is shocking to note that even the money-losing car ride company, Uber, which has no physical assets and less than one-tenth of the annual revenue of either Gazprom or Rosneft, commands a similar market capitalization of $48 billion.8Market capitalization values, dividend yield, and P/E trailing twelve months (ttm) statistics from https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/ April 17, 2020.

Investors see little improvement ahead, based on the companies’ price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples. The P/E ratio indicates how much investors are willing to pay for a company based on perceived future earnings power. For Gazprom and Rosneft, with P/Es of 2.8 and 4.7 respectively, they clearly do not. By comparison, investors see primary international competitors—Chevron (14.5), Exxon Mobil (17.3), BP (19.1), Royal Dutch Shell (8.7), Total (8.3), ENI (214.7), and Equinor (22.8)—as much better bets.9Market capitalization values, dividend yield and P/E (ttm, or trailing twelve months) statistics from https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/ April 17, 2020.

Why, then, are these two companies so poorly valued by global stock markets?

A first place to look is efficiency, specifically how much revenue each company makes per employee. In 2019, each of Gazprom’s 473,800 employees brought in $249,727. Each of Rosneft’s 334,600 workers yielded $400,540 in revenue. By comparison, Western energy companies are in another league: BP took in over $4.0 million per employee and Royal Dutch Shell $4.2 million.

Dividend yield is another yardstick. Gazprom and Rosneft have significantly increased their dividend payouts in recent years. At present, Gazprom offers a high dividend yield of 10.1 percent of the stock price, and Rosneft 11.7 percent,10Market capitalization values, dividend yield and P/E (ttm, or trailing twelve months) statistics from https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/ April 17, 2020. which is much higher than what other global energy companies offer. That would usually be welcome news to investors, but due to the ownership structure of Gazprom and Rosneft, those dividends flow primarily to the Russian treasury, but more important is that owners of stocks of these companies receive nothing but the dividend, so these stocks are traded as if they were bonds, as the shareholders are in no meaningful fashion owners of these companies. In late 2019, Gazprom stopped paying a flat dividend and instead pegged the dividend amount to its earnings, likely due to concern about recent lower energy prices.

Finally, global investors’ wariness of investing in Russia does not help market valuations, but a high market valuation for Russia’s national champions has never been the Kremlin’s priority. Alexei Miller, chief executive of Gazprom since 2001, has seen his company lose over $300 billion in market value since 2008 and has stayed in Putin’s good graces. Putin’s key objectives for Russia’s national champions lie elsewhere.

The value that Gazprom and Rosneft hold for the Kremlin is in their ability to further the domestic economic, political, and even personal goals of Putin and those close to him, including maintaining employment and social and economic stability in Russia’s far-flung, economically struggling regions; supporting commercially unsustainable undertakings; and providing what many experts contend is a continuous source of plunder to Putin and Co.

Oil and gas market dynamics have changed a great deal since 2006, when Putin boasted to Russian lawmakers that Gazprom had become “the third biggest company in the world in terms of capitalization.”11Vladimir Putin, “Annual Address to the Federal Assembly” (speech, Moscow, Russia, May 10, 2006), http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/23577. A decade later, Putin was asking his government to find ways to square the circle between its budget commitments and falling oil and gas prices.12Vladimir Putin, “Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly” (speech, Moscow, Russia, December 1, 2016),

http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/53379. More recently, the value of Russian Urals oil has been stuck for two months below $42.40 per barrel, the level at which Russia can balance its budget, though officials say they have enough put aside to ride out the turbulence. It even touched $10 per barrel. Natural gas prices have fallen correspondingly from a level around $400 per one thousand cubic meters in Europe in early 2014 to a low of $80 per one thousand cubic meters.

Gazprom’s Business Strategy

In its 2018 annual report, Gazprom defined its strategic goal as “establishing itself as a leader among global energy companies by diversifying sales markets, ensuring reliable supplies, driving operational efficiencies, and leveraging [research and development] R&D capabilities.”13RJSC Gazprom Annual Report 2018, Gazprom, January 24, 2019, https://www.gazprom.com/f/posts/67/776998/gazprom-annual-report-2018-en.pdf. Gazprom pursues Russia’s geopolitical interests by using its foreign deals to overcome competition by lessening the attractiveness of alternative suppliers and by using its pipelines to try to monopolize gas deliveries.

In recent years, this strategy has become less effective as Gazprom is facing an array of new challenges:

- An explosion in the global supply of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

- Competitors’ larger capital investments.

- The rise of alternative suppliers and transit routes.

- Western sanctions and European regulatory actions, all against the backdrop of lower oil and gas prices compared to the last decade.

Since the vast West Siberian gas fields were developed in the early 1970s, the Soviet and later Russian gas strategy has been to export natural gas through pipelines to Europe. Gazprom, formed out of the old Soviet Ministry of the Gas Industry, once had a state monopoly on gas production, sales, and exports. With ample reserves of cheap conventional gas in West Siberia, Gazprom has no interest in developing shale gas. Its relations with other former Soviet republics have been miserable, with disputes with both suppliers in Central Asia and customers in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. Today, Gazprom has ended almost all supplies from Central Asia, and the only former Soviet republics to which it delivers gas are Belarus, Moldova, and Armenia. Possible large gas supplies to China have been discussed for years, but they remain limited. Gazprom has essentially stuck to pipelines, and it controls only one LNG plant on Sakhalin, a majority stake which it strong-armed from a consortium led by Royal Dutch Shell in 2006.

Russian gas production has hovered around 600 billion cubic meters (bcm) annually since the collapse of the Soviet Union (Table 1). Gazprom has ample additional supplies. Production is adjusted to demand. Gazprom’s problem is not producing gas but selling it.

For a decade, Gazprom annually exported to Europe 139 to 163 bcm of natural gas, but from 2016 to 2018, its exports to Europe surged to 201 bcm (Table 2) as the company became more flexible in its pricing. European gas prices had climbed to record highs in 2018 after a harsh winter, but prices plummeted in 2019 and in early 2020 fell to their lowest level in a decade. Carlos Torres-Diaz, an expert on gas markets at the Rystad Energy consultancy, credited US attempts to elbow into the European market with starting a “race to the bottom” with Russia that pushed prices down.14Rystad Energy, “European Gas Prices Fall to One-Decade Low,” OilPrice.com, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Gas-Prices/European-Gas-Prices-Fall-To-One-Decade-Low.html.

In the last decade, Gazprom has increased its share of European gas supplies. It now holds the largest single chunk of the market, at 37 percent in 2018, compared with 27 percent in 2011, while Norway comes second with 27 percent.15“Gas Marketing in Europe,” Gazprom, https://www.gazprom.ru/about/marketing/europe/. Gas consumption in Europe, Gazprom’s key market, will likely stay flat in the medium term, while its production drops slightly as a Dutch facility is phased out and the North Sea fields decline. That might mean that Europe will need to import more energy, but Europe has been very successful in energy saving. Russia is ready to meet greater demand, but European customers are clearly looking for alternatives: European LNG imports more than doubled in 2019, led by a wave of shipments from the United States, and Europe is looking intensely to energy saving and renewables.

The LNG Challenge

The massive increase in Liquified natural gas (LNG) production by the United States and other producers such as Australia is a game changer. The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Gas Report for 2019 predicted that by 2024, US LNG annual exports will skyrocket to 113 bcm (from none in 2014) and Australian exports to 107 bcm (from 30 bcm in 2014).16International Energy Agency, Gas 2019: Analysis and forecasts to 2024, IEA, June 2019, https://www.iea.org/reports/market-report-series-gas-2019. Additionally, Qatar continues to annually export 105 bcm.

Increased global LNG supply will create more competition in the burgeoning Asia-Pacific market. Gazprom expects Asia will double its natural gas imports by 2035 and become the world’s largest natural gas consumer. China alone is expected to quadruple its annual LNG imports to 110 bcm. If tensions between the United States and China, however, threatened US shipments, US suppliers would likely seek to send more LNG to Europe. In the meantime, the shipments already landing on European shores have made a major difference in the market. Countries are able to sign shorter supply contracts and take advantage of more flexible trading structures, new transit arrangements, and, of course, more competition. What’s more, the US entry into the market will likely mean a more secure global energy supply, putting an end to Gazprom’s pipeline stoppages and high-pressure contract negotiations. Gazprom has almost completely missed the boat with LNG. Total Russian LNG production is expected to grow from currently 27 bcm to 38 bcm in 2024. Gazprom has only one LNG plant, on Sakhalin, in which the company forced a Shell-led consortium to sell it a majority stake in 2006.17Thane Gustafson, The Bridge. Natural Gas in a Redivided Europe (Harvard University Press, 2020), 305. Gazprom has considered new LNG projects but seems unlikely to complete them in the medium term. Among them is the third train of Sakhalin II and Baltic LNG—where Shell pulled out of an early agreement in April 2019 when Gazprom moved to integrate it with a gas processing chemical plant owned by RusGazDobycha, which has close links to businessmen sanctioned by Washington.

Prigorodnoye production complex, Sakhalin II project. Source: Gazprom

Russia’s best hope for LNG exports is not Gazprom, but Novatek, an independent company that has been around for twenty years and is listed on the Moscow and London stock exchanges.

Novatek’s major shareholders are closely related to President Vladimir Putin. They are Leonid Mikhelson, the chief executive officer (CEO), with around 28 percent of the shares; Volga Group, a privately held investment vehicle associated with Putin circle insider Gennady Timchenko, with 23 percent of shares; French Total SA with 16 percent; and Gazprom with 9.4 percent.

The biggest Russian producer of LNG, Novatek, earned $12 billion in revenues in 2019. It opened the Yamal LNG, the first non-Gazprom LNG production facility and export terminal, in December 2017, with help from the Kremlin. The government gave the project tax holidays and built nearby infrastructure to support it. Novatek is working on a second LNG terminal in Yamal.

None of these projects, however, will produce LNG before 2023 or 2024. At least until then, Gazprom will still overwhelmingly depend and compete on the basis of its pipelines and long-term gas supply contracts supported by its low-cost production. Will this old business model adapt to a new market reality?

An investment strategy benefiting contractors

Putin’s friends have been accused of making staggering fortunes off the back of Gazprom. Adding up the market value of the assets the energy company transferred to this gang of insiders and the privileged contracts they received from 2004 to 2007, opposition politicians Boris Nemtsov and Vladimir Milov in 2008 arrived at the stunning sum of $60 billion.18Boris Nemtsov and Vladimir Milov, “Путин и «Газпром»,” Novaya Gazeta, September 4, 2008, https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2008/09/04/36679-putin-i-gazprom.

Some argue it was perhaps the greatest larceny in history.19Anders Åslund, Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019). 174. After Nemtsov and Milov’s report came out, Gazprom’s market capitalization collapsed from its $367 billion peak and has stayed low. Shareholders who had enjoyed a great ride of rising stock prices when investors still believed that Putin stood for good corporate governance suddenly realized that future profits were not intended for them but for Gazprom’s main contractors, who happened to be close friends of Putin.

Who were these cronies? Gennady Timchenko, who made his money on oil trading, gas production, and pipeline construction; brothers Arkady and Boris Rotenberg, one of whom, Arkady, is a major state contractor for roads and pipelines, and both of whom have built infrastructure for Gazprom and the Sochi Olympics; and Yuri Kovalchuk, chief executive officer of Bank Rossiya, who made his money by purchasing financial and media assets from Gazprom.20Boris Nemtsov and Vladimir Milov, “Putin. Korruptsiya (Putin. Corruption)”, 2011, 18-24. These four seem to be the most successful businessmen in Putin’s orbit, to judge from Forbes’ rich lists.21Forbes, ”200 Богатейших бизнесменов россии”, Russian Forbes, 2017, https://www.forbes.ru/rating/342579-200-bogateyshih-biznesmenov-rossii-2017.

A Sberbank Corporate and Investment Banking (CIB) report in May 2018 said Gazprom is run for the benefit of contractors, who specifically stand to gain from the company’s major pipeline projects.22Alex Fak and Anna Kotelnikova, Russian Oil and Gas, Sberbank CIB, May 2018, https://www.petroleum-economist.com/articles/corporate/company-profiles/2018/gazprom-continues-to-aim-high. The Sberbank CIB analysts called the company’s pursuit of these hugely expensive white elephants “value destruction.”

Russia has two major, Soviet-era pipeline systems for sending gas to Central Europe, one of which passes through Ukraine and the other through Belarus and Poland. They have a combined capacity of 193 bcm, just shy of the largest volume of gas, 201 bcm, Russia has ever sent to Europe in a single year.

Despite this huge existing capacity, Gazprom has been focused on building new export pipelines under Putin. A first pipeline, Blue Stream (16 bcm), went through the Black Sea to Turkey. Then came the much larger Nord Stream (55 bcm), through the Baltic Sea to Germany. Gazprom almost managed to complete Nord Stream 2 (also 55 bcm) in 2019, before US sanctions delayed opening to late 2020 or even 2021. In parallel, Gazprom completed the first of two planned channels of TurkStream (31.5 bcm) through the Black Sea.23Thane Gustafson, The Bridge. Natural Gas in a Redivided Europe, (Harvard University Press, 2020), 327.

Commercially, this extensive construction of pipelines, which will be able to carry 60 percent more gas than Gazprom currently sends to Europe, makes little sense. But aside from benefitting a different group of stakeholders, namely Gazprom’s contractors, they serve a geopolitical purpose. The Nord Stream and TurkStream pipelines are meant to allow Russian gas to bypass hostile neighbor Ukraine. The $55 billion Power of Siberia pipeline to China (38 bcm), completed in December 2019, is a hedge against market headwinds in Europe as competition heats up, renewables take hold, and sanctions give Russia less room to maneuver.

The Nord Stream and TurkStream pipelines are meant to allow Russian gas to bypass hostile neighbor Ukraine.”

Workers are seen through a pipe at the construction site of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, near the town of Kingisepp, Leningrad region, Russia, June 5, 2019. REUTERS/Anton Vaganov

As it sinks billions of dollars into these projects, Gazprom faces challenges from pipeline competitors. The Trans Adriatic Pipeline (10 bcm), for example, will carry gas from a pipeline in Turkey to southern Italy when it opens in 2020. It is backed by BP, Azerbaijan’s SOCAR, Italy’s Snam, Belgium’s Fluxys, Enagás in Spain, and Axpo in Switzerland. In Russia’s other neighborhood, a 55 bcm pipeline carries gas from Turkmenistan to China, giving both countries an alternative to Russia for their exports and imports, respectively.

Table 3 shows Gazprom’s revenue; net profit; earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA); capital expenditures; and free cash flow from 2016 to 2019. During these four years, Gazprom’s annual capital spending averaged $25.7 billion. Sberbank CIB calculated that only 40 percent of the company’s planned capital expenditures of $110 billion for 2019 to 2023 was necessary to support its current business.24Alex Fak and Anna Kotelnikova, Russian Oil and Gas, Sberbank CIB, May 2018, 5, https://www.petroleum-economist.com/articles/corporate/company-profiles/2018/gazprom-continues-to-aim-high. Despite its huge earnings, Gazprom’s lavish spending on capital projects leaves it with little free cash flow, to the detriment of shareholders.25Ibid.

To take the most extreme example, in 2011, Gazprom planned for $27 billion of capital investment, but as revenues unexpectedly doubled with rising gas prices, the company eventually spent $53 billion.26Gazprom Investor Day: Relieved about No New Negatives, Troika Dialog, Russia Market Daily, February 13, 2012, http://www.gazprom.com/f/posts/28/866895/gazprom_investor_day_2014_slides.pdf. To nearly double capital spending in a matter of months is not a picture of efficiency and forethought. It is difficult to avoid the impression that Gazprom management was just shoveling money out of the door, as one investor saw the situation.27Personal conversation with Anders Åslund in London in 2012.

In 2019, Gazprom said it would put as much as $160 billion into eighty-four oil and gas projects worldwide until 2025, potentially making it the single biggest spender among the world’s oil and gas companies.28Kenneth Rapoza, “Russia’s Gazprom Is Investing More In Oil & Gas Worldwide Than Rival Exxon,” Forbes, August 22, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2018/08/22/russias-gazprom-is-worlds-biggest-energy-investor/#1e1257de3553. Many projects, however, may ultimately be contingent on the future direction of oil and gas prices.

Gazprom is a major source of financing for sundry domestic social or political projects. In 2018, Gazprom connected 272 locations across sixty-six Russian regions to the gas grid, primarily in rural areas as a massive economic development/social benefit program. It also performed an exemplary act of political largesse with the $4.5 billion to $6.5 billion it purportedly spent on the 2014 Sochi Olympics, building a six hundred-room mountain resort, a skiing complex, a twenty-five-kilometer highway, and a new gas pipeline serving Sochi and the Krasnodar region.29Paul Starobin, “Putin’s Paradise,” The Anti-Corruption Foundation, City Journal, Spring 2017, http://sochi.fbk.info/en/price/. The Sochi projects alone amounted to 25 percent of Gazprom’s 2014 capital spending.

Gazprom will continue to be an important supplier of gas to Europe and Asia for the foreseeable future. However, due to new LNG production and supply dynamics, increased competition in many forms, Western sanctions, stricter European regulation, and buyers’ efforts to diversify their supplies, Gazprom can no longer call the shots in the market. Over the past ten to fifteen years, a seller’s market in Europe has become a buyer’s market. Though still a player, Gazprom is no longer the player. Pipeline power politics have become less relevant. Today, US LNG sets the gas prices in Europe.

Rosneft: A similar story?

Together with Gazprom, Rosneft is Russia’s prime cash cow, producing half of the country’s crude oil. Since its average production costs are small, it generates large rents. However, like Gazprom, it pursues large capital expenditures, mainly on acquisitions of other oil companies. Rosneft is generally considered more modern than Gazprom because most of its assets come relatively recently from private companies Yukos, TNK-BP, and Bashneft. Rosneft’s CEO since 2012 is Igor Sechin, who has been very close to Putin since the early 1990s.

Rosneft has very different origins from Gazprom. While Gazprom was all along a state company with limited international input, Rosneft greatly benefited from international involvement in Yukos, TNK-BP, and Bashneft. Since private companies dominated the Russian oil industry in the late 1990s, Russia has a real market for oil, and the trunk pipelines are not (yet) owned by Rosneft but by a separate state company, Transneft.

From the outset, Rosneft was much smaller, a remnant of state oil companies that the government had failed to privatize before the trend reversed into re-nationalization in 2003. It has compensated for its lack of production by being more aggressive, taking over other oil companies. A parlor game in Russia is predicting which private oil company Rosneft will gobble up next. Over time, Rosneft seems increasingly monopolistic and less efficient, as if modeling itself on Gazprom, a trend reflected in its poor stock price.

In addition to making money, Rosneft, like Gazprom, acts to advance Russian foreign and domestic policy objectives, sponsor pet projects of Russia’s ruling elite, and support domestic employment and social stability. Rosneft’s stated commercial goals are to:

- Expand its international presence.

- Grow its resources base.

- Improve its overall performance.

Rosneft has moved on these goals over the last fifteen years by going on a massive acquisition spree in Russia. It received Yukos’ confiscated assets in 2004 and bought TNK-BP in 2013 for $55 billion, more than Rosneft’s current market valuation.30Andrew Callus and Vladimir Soldatkin, “Rosneft Pays Out in Historic TNK/BP Deal Completion,” Reuters, March 21, 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-rosneft-tnkbp-deal/rosneft-pays-out-in-historic-tnk-bp-deal-completion-idUSBRE92K0IZ20130321. More recently, in 2016, Rosneft acquired the well-run company Bashneft on the cheap from the embattled Sistema, in a spectacle full of lawsuits and counter lawsuits.

Looking ahead, the global oil market will only get tougher. Prices are being pummeled by hardball market positioning between Moscow and Riyadh while demand for oil collapses during the coronavirus pandemic. Whenever this crisis ends, Rosneft will likely have to reckon with remaining high oil production in the United States, which was on track to become a net exporter until the market crashed in late winter 2020.31United States Energy Information Administration, “EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2020 explores the changing US energy mix through 2050 as consumption grows more slowly than production, particularly of oil, natural gas, and renewables, resulting in increasing exports and relatively stable CO2 emissions,” Press release, (January 29, 2020).

Russia’s gross oil export ability, on the other hand, will likely remain flat at approximately 8.5 mb/d from 2019 until 2024.32International Energy Agency, Gas 2019: Analysis and forecasts to 2024, IEA, June 2019, https://www.iea.org/reports/market-report-series-gas-2019. and CERA week presentation, Houston, March 11, 2019. As they did in the LNG revolution for gas, US oil suppliers will change the global oil market and make the supply more secure by giving buyers a wider choice.

From 2016 until March 2020, Russia cooperated with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), limiting its oil production to boost the global oil price. On March 6, however, Russia suddenly and surprisingly ended its cooperation with OPEC and launched a price war that has led to a halving of the oil price in just one week, potentially causing the Russian economy great damage. The driver behind this aggressive stance was Igor Sechin. The Russian Urals oil price almost instantly collapsed to $10 per barrel, which was less than acceptable to Russia. The private Russian oil companies succeeded in convincing Putin to change track within a few weeks, and Russia agreed to major oil production cuts without the presence of Sechin. It remains to be seen whether this was a real turning point of the power of Sechin and Rosneft or whether it was just a temporary setback.

Geopolitical objectives

Gazprom has been used as a vehicle for the Russian Federation’s foreign policy and has been notorious for frequently cutting supplies to Eastern Europe over trumped-up pretexts. A study by the Swedish Defense Research Agency concluded that Russia used “coercive energy policy,” such as supply cuts, strongarm pricing, and sabotage, fifty-five times from 1991 until 2006. Of these incidents, thirty-six had political and forty-eight had economic underpinnings. Gazprom was the dominant actor in sixteen of them. The main targets have been Lithuania, Georgia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova.33Jacob Hedenskog and Robert L. Larsson, Russian Leverage on the CIS and the Baltic States (Stockholm: Swedish Defense Research Agency, 2007), 46.

The two most disruptive and egregious supply shutoffs came later, to and through Ukraine in January 2006 and January 2009.

In the last decade, Gazprom has cast its eye farther afield than Europe, but except for the company’s major pipeline investments, its foreign ventures hardly seem to support its strategic competitive position. In 2018, Gazprom’s investment in Bolivia, where it has a 20 percent share, produced only 2.6 bcm of natural gas. Its investment in Libya, started in 2007, in which Gazprom has a 49 percent share, was poorly timed. It produced 2.1 mm tons of oil and only 0.7 bcm of gas in 2018, reflecting the ongoing security conflicts in that country. Vietnam’s Moc Tinh and Hai Thach South China Sea fields, where Gazprom has a 49 percent share, produced only 2.2 bcm of gas. Gazprom’s investments in Algeria, Iraq’s Kurdistan, Uzbekistan, or the German-Russian joint venture Wintershall Noordzee do not hint at any prospect for future market dominance. Other than Gazprom’s 51 percent ownership in Nord Stream, its other foreign investments (country of primary operations not Russia) delivered around $135 million in profit in 2019, a minuscule 0.7 percent of Gazprom’s total net profit in that year. At the same time, it is questionable whether these investments contributed to any Russian foreign policy benefit or resulted in anything more than a costly distraction.

In the last decade, Gazprom has cast its eye farther afield than Europe, but except for the company’s major pipeline investments, its foreign ventures hardly seem to support its strategic competitive position.”

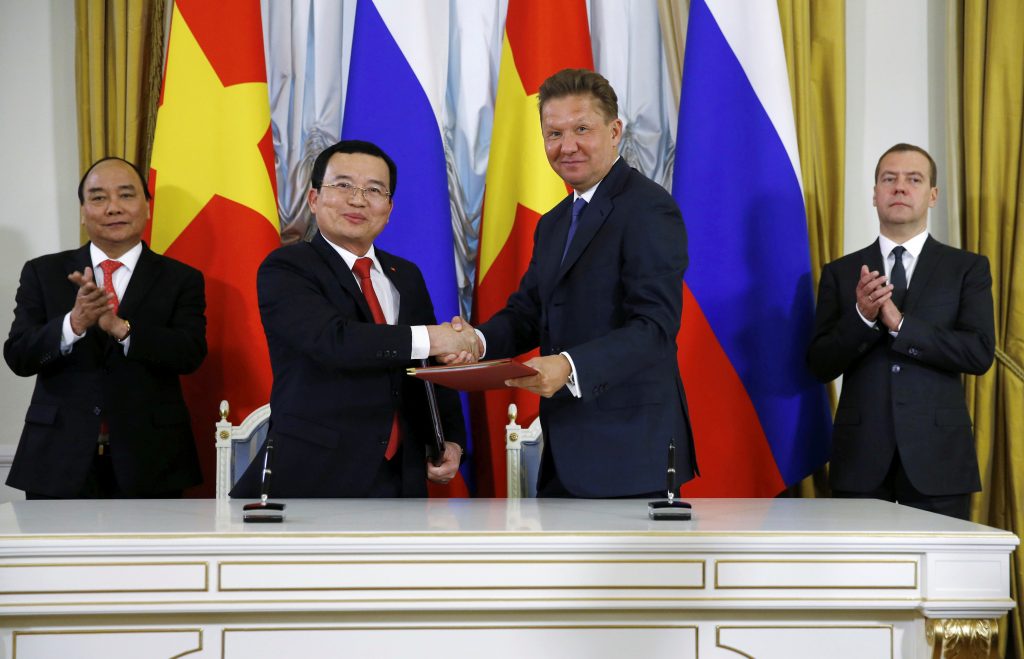

Alexei Miller (2nd R), chief executive of Russia’s natural gas producer Gazprom and Nguyen Quoc Khanh (2nd L), chief executive of the Vietnam’s state-owned oil and gas company PetroVietnam, attend a signing ceremony in the presence of Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev (R) and his Vietnamese counterpart Nguyen Xuan Phuc in Moscow, Russia, May 16, 2016. Dmitry Astakhov/Sputnik/Pool via Reuters.

Rosneft has been more ambitious abroad, often signing deals that carry significant geopolitical risks. Since 2010 it has invested $8.5 billion in Venezuelan oil with the cooperation of state-owned Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA). According to Reuters, “at the end of 2018, Rosneft had spent approximately $1.5 billion more in Venezuela than it had earned in the form of oil allocated to it as dividends.”34Christian Lowe and Rinat Sagdiev, How Russia sank billions of dollars into Venezuelan quicksand, Reuters, March 14, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/venezuela-russia-rosneft/. The future of this investment, given Venezuela’s current precarious state, is highly questionable.

Rosneft’s actions in the Middle East mirror the outreach in Russian foreign policy activity there. In 2015, Rosneft purchased a 30 percent share from Italian ENI of the Zohr Mediterranean field in Egypt, which produced 12.2 bcm of natural gas in its first year, 2018. Rosneft signed a $400 million deal with the Kurdistan regional government in October 2017 for cooperation to develop its oil and gas infrastructure, including the design of a new gas pipeline. In 2018, Rosneft inked a framework agreement with the United Arab Emirates-based Fleet Holding to study the feasibility of a joint venture to pump more gas to industrial customers in Egypt. In February 2019, Rosneft signed a twenty-year deal to manage and upgrade an oil facility in Lebanon’s second largest city, Tripoli. Last year, however, Rosneft backed off $30 billion worth of joint Russian-Iranian investments in oil and gas projects in Iran, citing US sanctions on Iranian oil.

Rosneft has also become more active in the Asia-Pacific and Africa. In August 2017, it bought a 49.13 percent stake in India’s Essar refinery company (renamed Nayara Energy Ltd. in May 2019), for a total transaction value of $12.9 billion. Rosneft’s 2019 financial statement lists that investment at 219 billion rubles, but 205 billion rubles of this amount is classified as “goodwill.” Rosneft’s share of the net income from Nayara Energy was 4 billion rubles, amounting to a negligible financial return of 1.8 percent on the recorded asset value.

Rosneft also recently signed agreements with Pertamina of Indonesia to build an oil refining and petrochemical complex in Tuban, Indonesia, and with China National Petroleum Corporation for a petrochemical project in Tianjin, China. In Africa, Rosneft has agreed to develop LNG product for delivery to the port of Tema with the Ghana National Petroleum Corporation. It also signed a memorandum of understanding on potential cooperation for oil and gas projects with Nigeria’s Oranto Petroleum.

In 2019, Rosneft’s total revenues were 8,676 billion rubles, of which only 100 billion rubles of revenue (1.1 percent) were attributed to equity share in profits of associates and joint ventures. Do not try making much commercial sense of these many large investments by Rosneft. Rather, look to Russian foreign policy and global assertiveness. For instance, Rosneft Chief Executive Igor Sechin is considered to be in charge of Russian policy on Venezuela.

Western sanctions

On March 20, 2014, two days after Russia’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea, the US Department of the Treasury sanctioned what it called “members of the inner circle,” Gennady Timchenko, Arkady and Boris Rotenberg, and Yuri Kovalchuk, as well as their jointly owned Bank Rossiya. They were sanctioned “because each is controlled by, has acted for or on behalf of, or has provided material or other support to, a senior Russian government official,” that is, Putin.35United States Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Russian Officials, Members of The Russian Leadership’s Inner Circle, And an Entity for Involvement in The Situation in Ukraine,” Press release, (March 20, 2014). Timchenko and the Rotenberg brothers build Gazprom’s unnecessary pipelines, while Kovalchuk manages their common finances.

In explaining its action against Bank Rossiya, the US Treasury noted that it is the personal bank for high Russian officials. In addition, the Treasury said, “Bank Rossiya’s shareholders include members of Putin’s inner circle associated with the Ozero Dacha Cooperative, a housing community in which they live. Bank Rossiya is also controlled by Kovalchuk, designated today. Bank Rossiya is ranked as the seventeenth-largest bank in Russia with assets of approximately $10 billion, and it maintains numerous correspondent relationships with banks in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. The bank reports providing a wide range of retail and corporate services, many of which relate to the oil, gas, and energy sectors.”36Ibid. The European Union followed suit, sanctioning Arkady Rotenberg and Yuri Kovalchuk, but not Timchenko and Boris Rotenberg, who had become Finnish citizens.

In July 2014, Russian military aggression proceeded in eastern Ukraine. The United States and the European Union responded with sanctions directed against the financing of Russian state enterprises and oil technology plus numerous individuals and companies. Washington and Brussels blocked medium- and long-term financing for Novatek, Gazprombank, Gazprom Neft, and Rosneft.37Kristin Archick et al., US Sanctions on Russia, Congressional Research Service, January 17, 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45415.pdf. Bowing to European pressure, the United States did not sanction Gazprom. However, Sechin, the Rosneft CEO, was placed on the US government’s sanctions list immediately after Russia’s takeover of Crimea, and Gazprom’s chief executive, Alexei Miller, was similarly sanctioned in April 2018.

Russian President Vladimir Putin (right) shook hands with his Venezuelan counterpart, Nicolás Maduro, at the Novo-Ogaryovo state residence outside Moscow, Russia, on December 5, 2018. (Reuters/Maxim Shemetov/File Photo)

Then in December 2019, the US Congress inserted sanctions against the Nord Stream 2 pipeline into the must-pass defense bill. US President Donald J. Trump signed the bill, and the Swiss company Allseas that had been laying the pipe in deep water halted its work instantly, leaving the pipeline incomplete for the time being.

Western sanctions have hampered Rosneft in several ways. It has become almost impossible to obtain large-scale, long-term US dollar financing for new projects (although Russian banks and Russia’s domestic ruble bond market have filled this gap to an extent). Second, sanctions on oil technology block the supply of advanced equipment, stunting Rosneft’s ability to invest and develop new areas for extraction in East Siberia, the Arctic, or offshore fields. This is of acute concern as Rosneft’s core assets in West Siberia and European Russia have been in decline for several years. As a result of these Western sanctions, ExxonMobil had to end most of its cooperation with Rosneft. Third, sanctions on Iran and Venezuela effectively prohibit investment, and fourth, sanctions on Sechin and his business partners potentially expose dubious transactions to increased scrutiny, risk, and negative publicity.

In February 2020, the US Treasury sanctioned Rosneft Trading S.A. in Geneva for helping to sell Venezuelan oil in violation of US sanctions.38United States Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Targets Russian Oil Brokerage Firm for Supporting Illegitimate Maduro Regime,” Press release, (February 18, 2020). Rosneft responded by selling its assets in Venezuela to a new Russian state company, which has been standard procedure for other territories subject to Western sanctions, such as Crimea. The most surprising thing about this case is that Rosneft did not bother to do so before, clearly underestimating the risk of US sanctions.

The EU antitrust case against Gazprom

In the past decade, European regulations and legal decisions have also complicated life for Gazprom and Rosneft, culminating in a major trust-busting decision in May 2018 against Gazprom.

Gazprom has long favored long-term “take-or-pay” contracts with its big clients in Western Europe, while its agreements with former Soviet republics had been of a completely different nature, with arbitrary pricing and shady middlemen. Both models came under pressure in the 2000s. As international gas prices rose, Gazprom wanted the freedom to hike its prices as well (shortly before the emergence of a spot market in Europe would help push prices down), while the former Soviet republics were tired of arbitrary prices and persistent crises with their gas supplies.

Gazprom’s January cuts of gas supplies through Ukraine, for four days in 2006 and especially for two weeks in 2009, were the last straw for the shivering Europeans, who demanded different trading rules with the company. In 2009, the European Union adopted its third energy package, which compelled the unbundling of energy supply and production from distribution networks. One consequence was that South Stream, a Russian gas pipeline project designed to deliver gas to the Balkans, was stopped by the EU rules. In August 2012, the European Commission opened an antitrust investigation into Gazprom’s monopolistic pricing and trading policies in Eastern Europe.

Gazprom has long favored long-term “take-or-pay” contracts with its big clients in Western Europe,”

A board with the logo of Gazprom Neft oil company is seen at a fuel station in Moscow, Russia, May 30, 2016. REUTERS/Maxim Zmeyev/File Photo

Three years later, the EU moved to create a unified energy market that, among other things, sought to relieve some members’ reliance on outside suppliers. An EU press release noted that six EU countries—Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Slovakia—depended on a single external supplier for all their gas imports.39European Commission, “Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to Gazprom for alleged abuse of dominance on Central and Eastern European gas supply markets,” Press release, (April 22 2015). https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_15_4828. All but Finland had suffered multiple politically motivated supply cuts.40Hedenskog and Larsson, Russian Leverage on the CIS and the Baltic States, 46. Though unnamed in the release, the sole supplier was Russia.

In April 2015, the commission expressed its preliminary view that Gazprom had broken EU antitrust rules by pursuing a strategy to cut off Central and Eastern European gas markets from the rest of the union. Shortly afterward, the Financial Times observed that, “dealing with Gazprom is a delicate matter. This is no ordinary parastatal enterprise, being as much a tool of geopolitics as an energy company. Vladimir Putin … made clear his hostility to the [EU] probe from the outset, passing a law forbidding state companies from passing information to foreign regulators without Moscow’s consent.”41“Vestager takes a tough stance on Gazprom”, Financial Times, April 21 2015, https://www.ft.com/content/c7f7807a-e826-11e4-894a-00144feab7de.

The commission’s three major concerns were Gazprom’s refusal to allow its customers to re-export its gas, monopolized markets that unreasonably inflated gas prices, and Gazprom’s use of its pipeline monopolies to seize markets.42European Commission, “Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to Gazprom for alleged abuse of dominance on Central and Eastern European gas supply markets,” Press release, (April 22 2015). The European Commission claimed that Gazprom had used monopolistic power in Central and Eastern Europe for geopolitical purposes. Gazprom decided to cooperate.43European Commission, “Antitrust: Commission invites comments on Gazprom commitments concerning Central and Eastern European gas markets,” Press release, (March 13 2017). https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-555_en.html.

On May 24, 2018, the commission ordered Gazprom to:

- Eliminate contractual barriers to the free flow of gas. Gazprom could not prohibit customers from reselling gas across the border.44European Commission, “Antitrust: Commission imposes binding obligations on Gazprom to enable free flow of gas at competitive prices in Central and Eastern European gas markets,” Press release, (May 24 2018). https://ec.europa.eu/energy/news/antitrust-commission-imposes-binding-obligations-gazprom-enable-free-flow-gas-competitive_en.

- Facilitate gas flows to and from isolated markets. Gazprom had to enable gas flows to and from the Baltic States and Bulgaria, which were still isolated from other EU members due to the lack of interconnectors.45Ibid.

- Abide by a structured process to ensure competitive gas prices. Relevant Gazprom customers were given an effective tool to make sure their gas price reflected the price level in competitive Western European gas markets, especially at LNG hubs.46Ibid.

- Stop leveraging dominance in gas supply. Gazprom could not use its dominance in gas supply to gain advantage in access to or control of gas infrastructure.47Ibid.

Essentially, Gazprom has been forced to change its business model in Europe. It can no longer extract high monopolistic prices or block resale of its gas. The natural consequence is that gas prices in Europe, Gazprom’s main market, will be much more competitive, to Gazprom’s disadvantage.

Arbitration losses

The opening of the European gas market has been a gradual process, starting with the third EU energy package of 2009. That was followed by European customers suing Gazprom for more flexible contracts and pricing (and Gazprom sometimes suing to enforce contracts).48“Arbitration cases pile up against Gazprom,” Naftogaz Europe, May 15, 2015, https://naftogaz-europe.com/article/en/slushanieiskakgazpromu. These verdicts, by the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, are not published, but the press has reported wins for some European gas purchasers.49“UPDATE 2-Gazprom dealt pricing blow as loses court case to RWE,” Reuters, June 27, 2013, https://www.reuters.com/article/rwe-gazprom-dispute/update-2-gazprom-dealt-pricing-blow-as-loses-court-case-to-rwe-idUSL5N0F32ZZ20130627; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-poland-russia-gas/polands-pgnig-to-take-immediate-steps-to-receive-15-billion-from-gazprom-idUSKBN21I1QY.

Judging from its annual accounts, Gazprom has had to pay several billion dollars every year in awards.50Thane Gustafson, The Bridge. Natural Gas in a Redivided Europe, (Harvard University Press, 2020), 371.

While Gazprom quietly paid its fines to European companies, it took a much tougher attitude to Ukraine, especially after Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity in February 2014. On June 16, 2014, Russia stopped delivering natural gas to Ukraine. The same day, Gazprom and Ukraine’s Naftogaz sued each other for contract violations at the arbitration tribunal. Because of Gazprom’s high prices and erratic supplies, Ukraine stopped importing gas from Russia in November 2015.51“Russia’s Gazprom Reduces Gas to Ukraine after Deadline Passes,” Reuters, June 16, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-crisis-gas-deadline/russias-gazprom-reduces-gas-to-ukraine-after-deadline-passes-idUSKBN0ER0KG20140616.

On December 22, 2017, the tribunal ruled in favor of Naftogaz on pricing, the contract’s take-or-pay clause, and other anti-competitive provisions, dismissing Gazprom’s demand to be paid for gas that Naftogaz had not purchased. The tribunal also revised the price formula, tying the price to market rates at European gas hubs, and it struck down the ban on gas re-export.52“The Stockholm Arbitration Tribunal rejects Gazprom’s “take-or-pay” claim regarding the Gas Sales Contract,” Naftogaz of Ukraine, May 31, 2017, http://www.naftogaz.com/www/3/nakweben.nsf/0/CD2D71060670AC07C2258131005777E4?OpenDocument&year=2017&month=05&nt=News&. Naftogaz’s victories largely coincided with the European Commission’s 2018 decision on Gazprom’s abusive practices elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe.

Later, Naftogaz won a net award of $2.6 billion in a case that claimed Gazprom had underpaid for gas transit through Ukraine, but Gazprom refused to pay.53Roman Olearchyk and Henry Foy, “Ukraine’s Naftogaz Claims $2.5 Billion Win over Russia’s Gazprom,” Financial Times, March 1, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/5ae3b27e-1d2f-11e8-956a-43db76e69936. Naftogaz responded by calling for a freeze on Gazprom assets in several European countries on the basis of the New York 1958 Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards. In December 2019, Gazprom relented and paid Naftogaz $2.9 billion to settle the case and to get Naftogaz to drop other litigation.54“Russia’s Gazprom to Pay Ukraine $2.9 billion before December 29 to Settle Row,” Reuters, December 21, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-ukraine-gas-payment/russias-gazprom-to-pay-ukraine-2-9-billion-before-december-29-to-settle-row-idUSKBN1YP08M. This case shows the strength of international arbitration. Although Russia initially loudly declared that it would not pay Ukraine, after Naftogaz had large Gazprom assets frozen abroad, Gazprom swiftly relented and quietly paid the whole amount in cash.

While Gazprom quietly paid its fines to European companies, it took a much tougher attitude to Ukraine, especially after Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity in February 2014.”

A man walks past the headquarters of the Ukrainian national joint stock company NaftoGaz in central Kyiv, Ukraine, March 15, 2016. REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko

The role of national champions

This litany of challenges has dented Gazprom’s and Rosneft’s market values as well as their relative global influence. Nevertheless, Russia’s two national resource champions together took in approximately $252 billion in revenues and $32 billion in net profits in 2019. Gazprom and Rosneft are the largest taxpayers in Russia, and together they employ over 800,000 people, or 1.1 percent of Russia’s current employed labor force.55CEIC Data, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/russia/employed-persons. They pay handsome annual dividends ($3.8 billion in 2018) to the Russian treasury and contribute to Russia’s large trade surplus. Indeed, they are very capable of continuing their work to benefit their masters.

There is a trade-off between maximization of shareholder return, including that of Russia’s treasury, and propping up Russian domestic and foreign policy objectives and enriching Putin’s circle. This way of doing business may be sustainable as long as Gazprom and Rosneft remain profitable and maintain fairly resilient financial structures (for example, healthy debt-to-equity ratios and sufficient liquidity). But in its inefficiency, this model is vulnerable to major shocks to the world economy that drive commodity prices lower, or to another technological revolution, including changes in renewable energy or in global energy dynamics as governments address the climate crisis. Amid the coronavirus pandemic and an oil-price war with Saudi Arabia, from January to mid-March 2020, for example, both companies’ stocks lost significant value, before clawing back some modest gains by early April.56“Public Joint Stock Company Rosneft Oil Company (ROSN.ME),” Yahoo Finance, April 2020, https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/ROSN.ME?p=ROSN.ME&.tsrc=fin-srch. At the same time, the price of a barrel of Russian Urals crude oil fell to less than half the benchmark price needed to balance the Russian budget.

Lucky for Russia, it has a bigger rainy-day fund and is more self-sufficient than before the sanctions were applied. But either way, in the long term, the country’s GDP growth and foreign trade surplus will continue to overly rely on oil and gas. When oil prices were high, oil and gas accounted for two-thirds of the value of Russia’s exports.

There is a trade-off between maximization of shareholder return, including that of Russia’s treasury, and propping up Russian domestic and foreign policy objectives and enriching Putin’s circle.”

Chief Executive of Rosneft Igor Sechin (C) and Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak (R) attend a Russian-Chinese business forum on the sidelines of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF), Russia June 7, 2019. REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov

Conclusions

Russia’s economic future is clouded by negative demographic trends, new competing energy technologies and efficiencies developed abroad, volatile commodity prices, and the likelihood of continued Western sanctions and anti-monopolistic regulatory actions. Another challenge is the power vertical of Putin and his inner circle, which does not reward independent entrepreneurship and therefore tends to pass over necessary and promising investments.

Gazprom and Rosneft do not necessarily work for all of their shareholders. Their continually depressed stock values show that investors who drew their conclusions in the last decade have not altered their view. Domestically, Gazprom and Rosneft are called upon to take care of sundry government matters and abroad they play a major geopolitical role which has turned out to be quite costly commercially. This dynamic is unlikely to change soon. There are some signs that the Russian oil and gas market is evolving so that Gazprom, Rosneft, and independent producers such as Novatek are pitted against one another, fostering greater efficiencies through competition. But pending more of that, it is possible to conclude that for now, new challenges and dwindling returns figure squarely in the scorecard for Russia’s two national champions.

About the authors

Anders Åslund is a resident senior fellow in the Eurasia Center at the Atlantic Council. He also teaches at Georgetown University. He is a leading specialist on economic policy in Russia, Ukraine, and East Europe.

Dr. Åslund has served as an economic adviser to several governments, notably the governments of Russia (1991-94) and Ukraine (1994-97). He is chairman of the Advisory Council of the Center for Social and Economic Research, Warsaw, and of the Scientific Council of the Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition. He has published widely and is the author of fourteen books, most recently Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy (YUP, 2019) and with Simeon Djankov, Europe’s Growth Challenge (OUP, 2017) and Ukraine: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It (2015). Other books of his are How Capitalism Was Built (CUP, 2013) and Russia’s Capitalist Revolution (2007). He has also edited sixteen books.

Previously, he worked at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Brookings Institution, and the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies at the Woodrow Wilson Center. He was a professor at the Stockholm School of Economics and the founding director of the Stockholm Institute of East European Economics. He served as a Swedish diplomat in Kuwait, Poland, Geneva, and Moscow. He earned his PhD from Oxford University.

Steven Fisher worked 35 years at Citi in various emerging markets corporate and investment banking leadership positions. He was Citi’s Corporate Bank Head in Moscow responsible for corporate client relationship businesses in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States during the oil price boom in the 2000’s. During that period, he led the origination and execution of an unprecedented amount of 155 syndicated loans and 50 Eurobond issues from issuers in that region exceeding a total value of $200 billion.

Steven has covered governments, emerging market corporates and multinationals his entire career. He has advised many governments and companies on the broadest menu of financial services including debt and equity capital markets, export credit financing, local and international currency funding solutions, liability management, derivatives, trade, cash management, and treasury solutions.

Steven has a Master of Science degree with honors from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and a Bachelor of Arts degree as a College Scholar in international relations from Cornell University.

He has been a frequent speaker at finance and policy forums, including those sponsored by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), International Finance Corporation (IFC), CFA Society, Euromoney, Adam Smith, U.S. Ukraine Business Council, New Ukraine Investment Conference and the Atlantic Council.

Steven has also lectured at universities located in the markets in which he has served including St. Petersburg State University Graduate School of Management and Kyiv National University of Trade and Economics.

Steven speaks fluent Mandarin Chinese, Russian, Spanish and has proficiency in Japanese and Thai.

This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The author is solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions.

Further reading

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to promote policies that strengthen stability, democratic values, and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe in the West to the Caucasus, Russia, and Central Asia in the East.

Image: Clockwise Top Left: A board with the logo of Gazprom Neft oil company is seen at a fuel station in Moscow, Russia, May 30, 2016. REUTERS/Maxim Zmeyev/File Photo; The Achinsk refinery, which was acquired by Rosneft company in 2007 and currently processes West Siberian crude delivered via the Transneft pipeline system, in Krasnoyarsk Region, Russia July 23, 2018. Picture taken July 23, 2018. REUTERS/Ilya Naymushin; A worker walks near a pipe at the construction site of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, near the town of Kingisepp, Leningrad region, Russia June 5, 2019. REUTERS/Anton Vaganov