Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Qatar regard Tunisia as an important foreign policy partner within their regional sphere of influence. They also welcome Tunisia’s current autocratization under President Kais Saïed. However, Gulf states no longer pursue strategic goals there. As the region is undergoing a geopolitical shift toward more conflict management and reconciliation, the Gulf states consider Tunisia as a partner of choice in regional stability but no longer as a partner of necessity in terms of economic investment or development cooperation.

Three phases of Gulf engagement in Tunisia since the “Arab Uprisings”

In the last decade, Gulf Arab engagement has gone through three phases in Tunisia that have been characterized by different priorities and motivations. The first phase started in the direct aftermath of the “Arab Uprisings” and the fall of Tunisia’s longtime autocrat Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali, resulting in what could be defined as the “Gulf moment.” This was characterized by increased political, developmental, and economic involvement of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and, above all, Qatar. During this phase, Tunisia became a theater of inter-Gulf rivalry after Qatar, under the leadership of then Emir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani (r. 1995-2013), initiated a largely ideologically motivated regional policy that included support for Islamist groups such as the Ennahda Party in Tunisia. The counter-revolutionary regional forces of Saudi Arabia and the UAE viewed this pro-Islamist policy of regional power projection as a direct threat to their own autocratic-monarchical system of rule. During Ennahda’s reign, Qatar rose to become the second-most important investor for the Islamist government in the form of budget support and investment in Tunisian infrastructure, providing some political stability. At the same time, Saudi Arabia and the UAE reduced their political support to a minimum, which also affected their economic and development activities in Tunisia in the medium term.

The second phase was characterized by intensifying inter-Gulf competition, in particular during the “Gulf crisis” between June 2017 and January 2021. This rivalry between the “blockading quartet” (Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt) on the one hand and Qatar on the other also played out in Tunisia, which emerged as a hotbed for inter-Gulf competition. Similar to other countries, inter-Gulf regional tensions in Tunisia caused an increasing polarization of the public discourse, as certain media defamed and demonized the respective conflict parties, thus intensifying political fragmentation within Tunisia’s heterogeneous political system. At that time, ties between Qatar and the Islamist government grew whereas Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman faced public protests during his 2018 visit. In the wake of this rivalry, the UAE and Saudi Arabia increased their efforts to reduce the Islamists’ political relevance, indicated by the surveillance of Rachid Ghannouchi, senior member of Ennahda.

As most Gulf states are undergoing a fundamental socioeconomic transformation, they are strongly interested in regional reconciliation as a prerequisite for economic progress. They need to preserve their specific business models, and are thus inclined to less ideological conflict and more tactical pragmatism. Against this backdrop, the current agreement between Saudi Arabia and Iran to resume diplomatic ties in March 2023exemplifies the kingdom’s shift in regional policy from competition to coexistence, occurring after five rounds of talks among Iranian and Saudi security officials starting in 2020 and facilitated by Iraq and Oman. Additionally, Syria was reintegrated into the Arab League in May 2023, twelve years after its membership was suspended, which again indicates the Gulf interest in conflict management. Conflict theatres such as Yemen, Iraq, the Horn of Africa, and Iraq have become more important for the Gulf states in recent years, resulting in enhanced political and economic engagement.

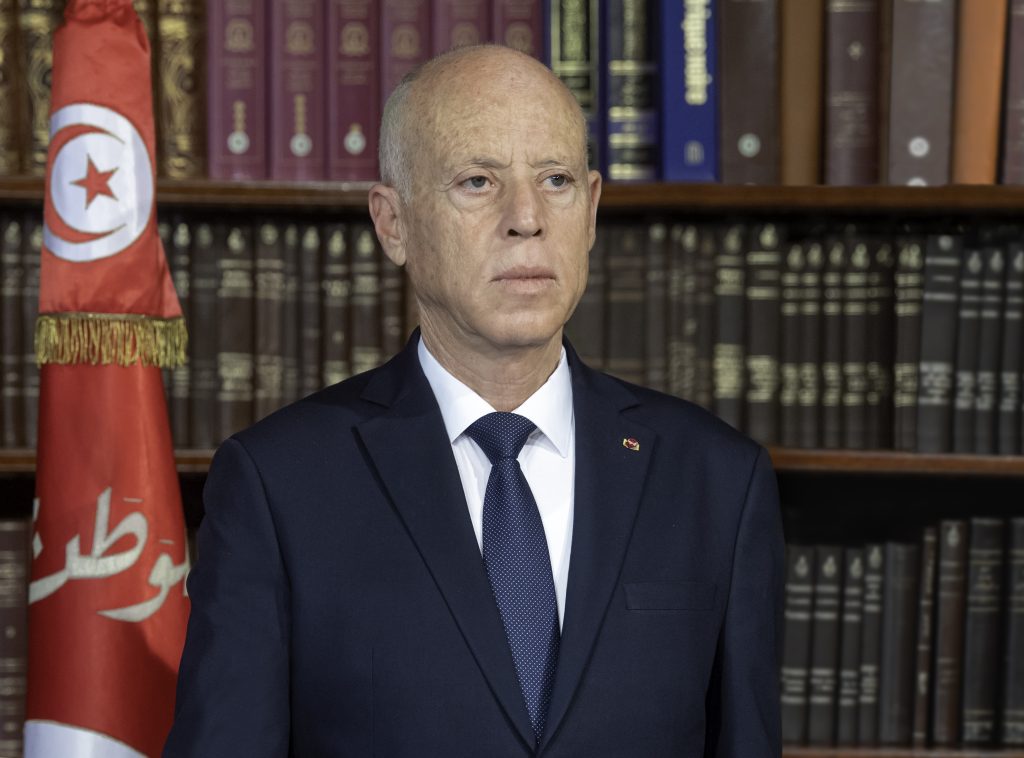

Accordingly, Tunisia has become less relevant during the current third phase: Since ties among the “blockading quartet” and Qatar were resumed in January 2021, the inter-Gulf polarization has decreased. Furthermore, the turn toward more authoritarianism is welcomed by both Saudi Arabia and the UAE and considered as a cornerstone of Tunisia’s stability. Saïed’s power consolidation thus serves the Gulf states’ aspirations to restore the pre-Arab Uprising status quo. For example, the dissolution of Tunisia’s parliamentwas endorsed by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, while Qatar has largely ceased its support for the Islamists: Saïed had traveled to Qatar in November 2020 to discuss intensifying economic cooperation with Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani. During the growing intra-Tunisian protests, both leaders spoke on the phone to explore possibilities for Qatari mediation among the conflicting parties, again demonstrating Qatar’s new pragmatic positioning in the Tunisian power struggle. In addition, the Gulf states did not publicly criticize Ghannouchi’s detention in April 2023.

Limited political, financial, and economic engagement

From the Gulf states’ perspective, the return of authoritarianism under Saïed has been a success that needs to be preserved—but not at all costs. As other regional conflicts deserve greater attention and effort, the Gulf investments in Tunisia on political, financial, and economic fronts are limited. Politically, Saïed is officially promoted as a partner in regional stability; he participated in the summit of the Arab League in Jeddah and enjoys conciliatory ties with Gulf governments. Nevertheless, his government does not play an influential role in the regional powerplay.

While the “politicization” of Gulf aid was essential in the Gulf economic statecraft vis-à-vis Tunisia in the aftermath of the Arab Uprisings, volumes were significantly low in comparison to those of other main recipients of Gulf humanitarian assistance such as Yemen. Between 2013 and 2017, Tunisia ranked as the tenth-most-important recipient state of Gulf Arab support, largely due to Qatar’s substantial contribution. However, assistance to Tunisia accounted for only 1.6 percent of total aid during this period and appears to have declined even further since then. Between 2012 and 2022, official development assistance (ODA) from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE, and Qatar to Tunisia amounted to US$29.9 million (from in total $105 million in ODA). Most of the aid for Tunisia has been provided by the Gulf monarchies in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic as part of their “vaccine” and “health diplomacy.” This engagement was particularly evident in the case of the UAE in 2021 and 2022, with ODA exceeding $22.5 million. At a time of economic diversification, the Gulf states’ development assistance is undergoing a significant shift. The provision of unconditional aid has become more unlikely as the Gulf states are more interested in return on investment and long-term business-development relationships that serve their national economic interests. This trend was outlined by Saudi Finance Minister Mohammed Al-Jadaan in January 2023. In Davos, he said that “we used to give directs grants and deposits without ‘strings attached’ and we’re changing that…. We’re taxing our people, so we’re expecting others to do the same. We want to help but we want others to do their part.” In his statement, he referred to the introduction of a 5 percent value-added tax in the kingdom, which was increased to 15 percent in July 2020. In light of this shift, financial aid provision to Tunisia is likely to decline further.

Economically, if put into a regional perspective, Tunisia plays only a minor role in Gulf Arab investments. With a population of about twelve million, it remains a small market that is mainly dependent on imports from European countries such as Italy (14 percent of all imports in 2021) and France (12 percent), but also China (11 percent). The same year, Tunisia’s main export partners were France with 26 percent, Italy at 20 percent, and Germany at 14 percent. In contrast, imports from the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries accounted for only 0.59 percent in 2021, with Saudi Arabia as top trading partner with a share of 2.2 percent of all imports. Regarding exports, Tunisia supplies goods with a share of only 0.21 percent to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman. The top GCC export partner is the UAE with 0.61 percent. Despite the low trade volumes, Qatar in particular has established itself as the second-most-important investor in Tunisia after France. Qatar’s proximity to the political leadership under Ennahda at the time and its pragmatic and business-friendly relationship with the current government are helping it to expand its investments in the country. Since 2015, the Qatar Investment Authority has provided economic support to Tunisia with substantial investments in real estate, tourism, banking, media, telecommunications, and petrochemicals and in 2016, Qatar’s emir announced support to the crisis-torn Tunisian economy of $1.25 billion. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are mainly engaged in prestigious infrastructure and real estate projects such as Tunis Sports City in which the Emirati Bukhatir Group is invested. In addition, the Tunisian government has contracted UAE company AMEA Powerto implement a 100 megawatt solar project in Kairouan with a total budget of $100 million.

New areas for Gulf engagement in Tunisia

In times of shifting geopolitical priorities and ongoing domestic economic diversification, the Gulf states’ engagement with Tunisia will most likely focus only on specific areas to preserve authoritarian stability in the country. While financial assistance and economic investment will remain limited and mainly attached to political motivations, other sectors such as education, green entrepreneurship, and capacity development could become more relevant. For example, development policy projects are intended to promote job creation and educational opportunities to improve social crisis resilience in Tunisia. Already, in 2015, the Qatari philanthropic institution Education Above All (EAA) implemented two projects, “Jendouba Works!” and “My Education … My Hope.” In recent years, Qatar’s Silatech has provided financial and technical support to Tunisian start-ups and companies working in microfinance. Based on these already established networks, private-sector and philanthropic initiatives could help to promote Tunisian entrepreneurship and start-ups in the future, thus strengthening the investment environment. In particular, green entrepreneurship could become a driver for the Gulf monarchies’ future engagement with the country: As Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Oman are investing in renewable energies such as hydrogen, Tunisia could become an interesting partner for bilateral cooperation and knowledge transfer. Saudi Arabia could potentially promote collaboration in climate action with Tunisia as part of the kingdom’s Middle East Green Initiative. In light of the UAE’s climate diplomacy efforts, indicated by its hosting the twenty-eighth United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28), Emirati stakeholders could also extend their interest to promote joint projects related to environmental sustainability with Tunisian partners such as the national development cooperation agency Agence Tunisienne de Coopération Technique. Finally, Qatar’s EAA has recently launched Education for Climate Action increase its focus on environmental education for school children, which could represent another interesting field of joint collaboration with Tunisia.

Sebastian Sons is a senior researcher a the Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient (CARPO)

In partnership with

Related content

Image: Tunisian President Kais Saïed's power consolidation serves the Gulf states’ aspirations to restore the pre-Arab Uprising status quo. | Houcem Mzoughi