In partnership with

The war in Ukraine is further diverting US attention from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region where Russia and China have expanded their footprint over the past decade. US President Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s upcoming visit to the Middle East—his first since he took office—provides an opportunity to assess the kind of role the United States will play in the MENA region in the future. The big question is whether the region is entering a post-US era and how the new regional order will be structured.

Over the past decade, the MENA region has undergone profound geopolitical transformations as a result of both the Arab Spring uprisings of the early 2010s, which intensified competitive dynamics triggered by the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 that paved the way for Iran’s increasing influence, and former US President Barack Obama’s pivot to Asia, which resulted in the United States drawing down its military presence in the region. US inaction in the wars in Syria, Libya, and Yemen paved the way for fierce geopolitical competition among the main Middle Eastern states and created an opportunity for Russia and China to strengthen their ties with countries in the region.

After years of conflict and destabilizing competition, diplomacy today seems to be the new mantra of many MENA leaders. As a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic and widespread conflict fatigue, these leaders can hardly afford the burden of costly confrontations. However, the outcome of this new diplomatic course is uncertain, as some normalization processes are still fragile, while rivalries and tensions are far from being assuaged.

Against this backdrop, the socioeconomic implications of the war in Ukraine have cast a shadow on countries in the MENA region already affected by longstanding structural vulnerabilities. The war is also likely to affect security in the MENA region as a consequence of both the US administration’s refocus on Eastern Europe and Russia’s increasing strategic role in the Middle East, although how and to what extent remains unclear.

This Dossier, a joint effort by the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI) and the Atlantic Council’s North Africa Initiative, explores how decade-old geopolitical transformations have changed the balance of power in the MENA region and examines the actions of old and new external actors in this shifting regional order.

As Maha Yahya writes in her essay, Washington’s recalibration of its engagement with the region since the Obama administration has fuelled the perception in MENA governments that the United States is reducing its commitment, especially as a security provider. A sense of abandonment has permeated Arab countries, particularly Gulf countries that rely on the US security umbrella and feel more directly exposed to the threat posed by Iran.

Jonathan Panikoff argues that the narrative in Washington is slightly different: The MENA region remains a priority, but it is no longer the priority of US foreign policy. In this new context, the future of the United States’ relationship with the region depends on its ability to balance attention to its Arab partners with its focus on China and, more recently, Russia.

As Sanam Vakil highlights, the war in Ukraine has revealed the frustrations of Arab countries vis-à-vis the United States as well as the depth of relations they have established with Russia in the energy, economic, and military sectors over the years. This explains why many of these countries have so far avoided taking sides in the confrontation between the West and Russia over Ukraine. In his essay, Mark Katz argues that exploiting the MENA region’s frustration with the United States, Russia has skillfully strengthened ties with US partners and allies in the region. MENA countries appreciate Russia’s non-interference in their internal affairs—specifically, a lack of criticism of the democracy deficit and poor state of human rights in the region—as well as its staunch support for Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria.

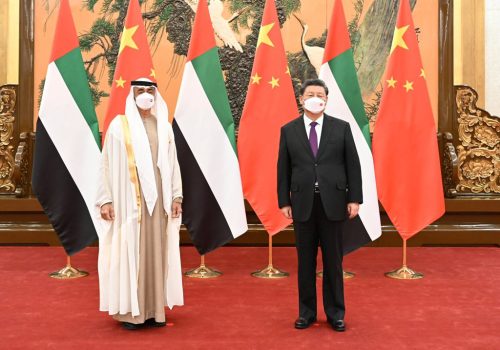

Besides Russia, the MENA region has witnessed an increasing Chinese mainly concentrated in infrastructure, trade, and energy. However, while China is one of the largest trading partners of the Middle Eastern countries, the main destination of energy exports from the Gulf, and a major investor in the region, it is hesitant to deepen its engagement in a region affected by conflicts, ethno-religious violence, and political instability, as She Ganzheng writes. China is focused on increasing its influence in the Middle East while protecting its interests.

With the United States rebalancing its global priorities and the growing role of Russia and China in the MENA region, Europe needs to become a more relevant geopolitical actor, as Julien Barnes-Dacey writes. By doing so, it could influence positive trends in a region that has increasingly shifted toward a multipolar order and minimize the spillover effects of its instability.

Whether the MENA region moves toward a more stable order remains to be seen. Much will depend on the role regional actors and external powers, including the United States, are willing to play.

Karim Mezran is director of the North Africa Initiative and resident senior fellow with the Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East Programs at the Atlantic Council focusing on the processes of change in North Africa.

Valeria Talbot is a Senior Research Fellow and Co-Head of ISPI’s Middle East and North Africa Centre, in charge of Middle East Studies.

A post-American era for the Middle East and North Africa: What’s next for the region?

Related content

Image: US Vice President Joe Biden (C) is greeted by Saudi Foreign Minister Price Saud Al-Faisal upon his arrival at Riyadh airbase October 27, 2011. Biden led an American delegation to offer his condolences on the death of late Saudi Crown Prince Sultan bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud. REUTERS/Fahad Shadeed