General Motor’s (GM) electric vehicle (EV) transition—aimed at phasing out gas and diesel engines by 2035—represents a reversal for the automaker once accused of killing the electric car. The change portends a sweeping transformation of the US car industry, and the federal government, states, unions, supporting industries, and individual firms must adapt quickly to survive.

GM’s embrace of new EV technology furthers its ambition to become a tech company. The tech industry has long encroached on Detroit’s automotive turf, with audio and navigation intrusion escalating to ridesharing and autonomous vehicles. GM has responded by integrating itself within Silicon Valley’s technological ecosystem, adapting its business model for the high-tech era.

Big tech dominates clean energy investment, but decarbonizing transport is the domain of newer players. EV start-ups, blurring the line between tech and auto, have proliferated; Fremont, California-based Tesla, the first such company to breach the Fortune 500, exemplifies their collective potential. In fact, a burgeoning Tesla-GM rivalry embodies broader trends within the US auto industry.

Last December, Tesla’s market capitalization surpassed the world’s next nine carmakers combined, with some asset managers predicting a multi-trillion dollar valuation. Such market euphoria eludes traditional automakers; GM’s stock trailed its 2010 initial public offering price until last October, despite overperforming earnings estimates for twenty-two consecutive quarters. Investors believe newer, specialized EV firms can rapidly scale innovations to disrupt the market. But GM bets it can outcompete the newcomers by marrying novel technology to extant industrial might.

That has not been easy. Collaboration with Nikola was curtailed as the start-up struggled to convert questionable technological claims into real-world production. Instead, GM will retool its Detroit-Hamtramck factory—rebranded ‘Factory ZERO’—for its own EV production.

The transition will be uneasy for workers as well, since the lighter labor-intensiveness of EV manufacturing could threaten jobs. GM’s unionized workforce also faces competition from Tesla’s non-unionized production in Fremont and in lower-cost Texas and Nevada. EV manufacturing has thrived in Sun Belt states, whose governors are proactive in attracting that business. Detroit’s workforce will be bolstered by President Biden’s mandate that federal fleet electrification rely on union labor and US-made materials. But competition for the consumer market will be fierce.

Dealerships are also threatened because EVs break down less, imperiling maintenance-reliant business models. As is refueling; though gas stations might adapt to electric charging, alternatives like Tesla’s supercharger network—featuring high-capacity stations that top up batteries in minutes rather than hours and imitated by EV rival Rivian—presage the charging sector’s absorption into the auto industry. Simultaneously, dedicated charging start-ups have been ripe for speculation and acquisition. Legacy automakers must decide between integration or partnership models.

Charging remains a chicken-and-egg problem for the industry. Refuelling anxiety among consumers, alongside cost concerns, have limited EVs to 2 percent of new US automobiles. Consequent lack of demand has constrained private sector involvement. The administration’s recent infrastructure plan enlists government as first mover, allocating $174 billion to deploy half-a-million chargers by 2030, among other EV-related tax incentives.

The plan constitutes a nascent federal EV strategy, but the United States trails competitors like China and the European Union, which have each eclipsed the US share of the global market. Both made substantial investments in charging infrastructure while also lavishing consumers with purchase subsidies; US federal consumer subsidies, however, taper at a firm’s 200,000th EV sold, and now exclude both Tesla and GM purchases. Chinese start-ups and Europe’s adapting majors have prospered from government support to dominate their home markets. Tesla, meanwhile, has hemorrhaged market share in Europe and was recently restricted in China on far-fetched spying claims.

China’s performative protectionism suggests the still-infant industry might resemble the pre-globalized automotive world of the past. GM fortuitously retrenched, bankrolling its EV transition by auctioning unprofitable European, Russian, and Indian divisions. The company also simplified parts sourcing, now done across nine countries rather than twenty-five. GM’s onshoring of input procurement looks prophetic as Washington moves to secure critical supply chains, including for EV battery minerals. Those supply chains have also splintered domestically into three regional battery hubs that support nearby vehicle production—including Tesla’s Nevada Gigafactory and GM’s Ultium Cells manufacturing plant in Lordstown, Ohio—forming a crucial component of interregional competition.

For the US market to sustain numerous competitors, federal strategy must replicate subsidy and infrastructure successes in China and Europe. Electrifying the federal fleet should encourage ramped up EV production, but pricing and supporting infrastructure will determine greater consumer market outcomes. As plans progress to address the latter, developing cheaper batteries is critical for the former. Meanwhile, policymakers should negotiate reciprocal market access abroad to avoid a vicious protectionist cycle.

Though federal EV strategy remains embryonic, private sector developments have fostered a growing US EV market. As sectoral interests within the United States vie for this business, turnover is inevitable, for firms and regional manufacturing centers alike. Add a changing lineup of carmakers to the list of disruptions wrought on dealerships, gas stations, and the US autoworker; the American auto industry stands at the precipice of a revolution the likes of which it has rarely seen.

Paddy Ryan is a Spring 2021 Intern at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

Related content

Read more from this author

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

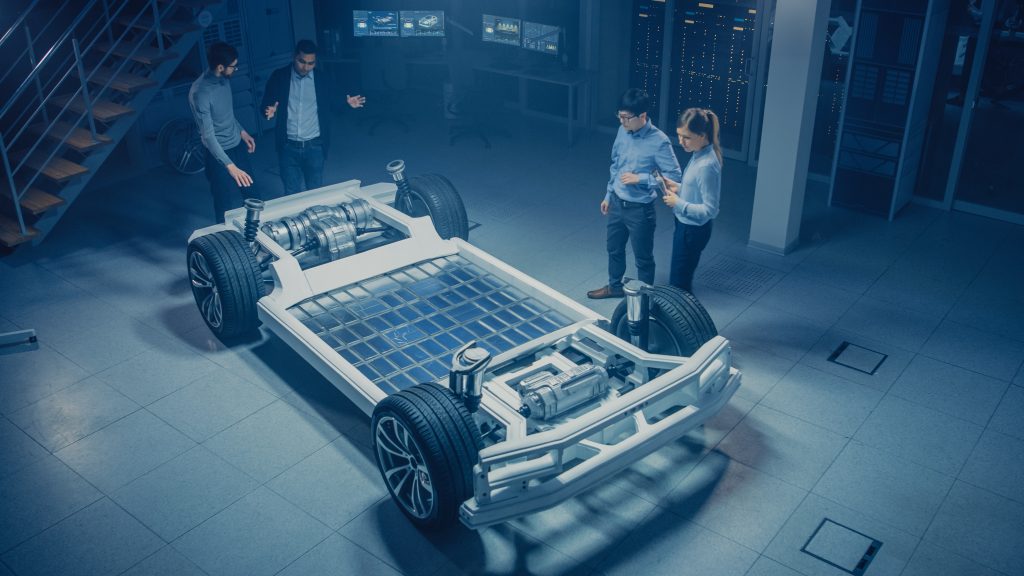

Image: Team of Automotive Engineers Working on Electric Car Chassis Platform (Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock)